полная версия

полная версияThe Emancipation of Massachusetts

These petitions were substantially those already presented, except that, by way of preamble, the story of the trial was told; and how the ministers “did revile them, &c., as far as the wit or malice of man could, and that they meddled in civil affaires beyond their calling, and were masters rather than ministers, and ofttimes judges, and that they had stirred up the magistrates against them, and that a day of humiliation was appointed, wherein they were to pray against them.” [Footnote: Winthrop, ii. 293.]

Such words had never been heard in Massachusetts. The saints were aghast. Winthrop speaks of the offence as “being in nature capital,” and Johnson thought the Lord’s gracious goodness alone quelled this malice against his people.

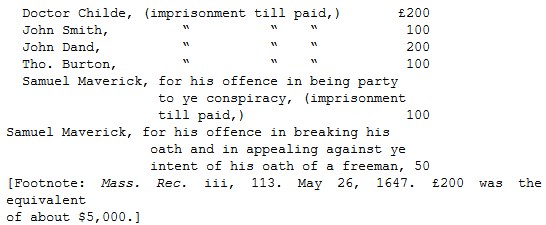

Of course no mercy was shown. It is true that the writings were lawful petitions by English subjects to Parliament; that, moreover, they had never been published, but were found in a private room by means of a despotic search. Several of the signers were imprisoned for six months and then were punished in May:—

The conspirators of the poorer class were treated with scant ceremony. A carpenter named Joy was in Dand’s study when the officers entered. He asked if the warrant was in the king’s name. “He was laid hold on, and kept in irons about four or five days, and then he humbled himself…for meddling in matters belonging not to him, and blessed God for these irons upon his legs, hoping they should do him good while he lived.” [Footnote: Winthrop, ii. 294.]

But though the government could oppress the men, they could not make their principles unpopular, and the next December after Vassal and his friends had left the colony, the orthodox Samuel Symonds of Ipswich wrote mournfully to Winthrop: “I am informed that coppies of the petition are spreading here, and divers (specially young men and women) are taken with it, and are apt to wonder why such men should be troubled that speake as they doe: not being able suddenly to discerne the poyson in the sweet wine, nor the fire wrapped up in the straw.” [Footnote: Felt’s Eccl. Hist. i. 593.] The petitioners, however, never found redress. Edward Winslow had been sent to London as agent, and in 1648 he was able to write that their “hopes and endeavours … had been blasted by the special providence of the Lord who still wrought for us.” And Winthrop piously adds: “As for those who went over to procure us trouble, God met with them all. Mr. Vassall, finding no entertainment for his petitions, went to Barbadoes,” [Footnote: Winthrop, ii. 321.] … “God had brought” Thomas Fowle “very low, both in his estate and in his reputation, since he joined in the first petition.” And “God had so blasted” Childe’s “estate as he was quite broken.” [Footnote: Winthrop, ii. 322.]

Maverick remained some years in Boston, being probably unable to abandon his property; during this interval he made several efforts to have his fine remitted, and he did finally secure an abatement of one half. He then went to England and long afterward came back as a royal commissioner to try his fortune once again in a contest with the theocracy.

Dr. Palfrey has described this movement as a plot to introduce a direct government by England by inducing Parliament to establish Presbyterianism. By other than theological reasoning this inference cannot be deduced from the evidence. All that is certainly known about the leaders is that they were not of any one denomination. Maverick was an Episcopalian; Vassal was probably an Independent like Cromwell or Milton; and though the elders accused Childe of being a Jesuit, there is some ground to suppose that he inclined toward Geneva. So far as the testimony goes, everything tends to prove that the petitioners were perfectly sincere in their effort to gain some small measure of civil and religious liberty for themselves and for the disfranchised majority.

Viewed from the standpoint of history and not of prejudice, the events of these early years present themselves in a striking and unmistakable sequence.

They are the phenomena that regularly attend a certain stage of human development,—the absorption of power by an aristocracy. The clergy’s rule was rigid, and met with resistance, which was crushed with an iron hand. Was it defection from their own ranks, the deserters met the fate of Wheelwright, of Williams, of Cotton, or of Hubbert; were politicians contumacious, they were defeated or exiled, like Vane, or Aspinwall, or Coddington; were citizens discontented, they were coerced like Maverick and Childe. The process had been uninterrupted alike in church and state. The congregations, which in theory should have included all the inhabitants of the towns, had shrunk until they contained only a third or a quarter of the people; while the churches themselves, which were supposed to be independent of external interference and to regulate their affairs by the will of the majority, had become little more than the chattels of the priests, and subject to the control of the magistrates who were their representatives. This system has generally prevailed; in like manner the Inquisition made use of the secular arm. The condition of ecclesiastical affairs is thus described by the highest living authority on Congregationalism:—

“Our fathers laid it down—and with perfect truth—that the will of Christ, and not the will of the major or minor part of a church, ought to govern that church. But somebody must interpret that will. And they quietly assumed that Christ would reveal his will to the elders, but would not reveal it to the church-members; so that when there arose a difference of opinion as to what the Master’s will might be touching any particular matter, the judgment of the elders, rather than the judgment even of a majority of the membership, must be taken as conclusive. To all intents and purposes, then, this was precisely the aristocracy which they affirmed that it was not. For the elders were to order business in the assurance that every truly humble and sincere member would consent thereto. If any did not consent, and after patient debate remained of another judgment, he was ‘partial’ and ‘factious,’ and continuing ‘obstinate,’ he was ‘admonished’ and his vote ‘nullified;’ so that the elders could have their way in the end by merely adding the insult of the apparent but illusive offer of cooperation to the injury of their absolute control. As Samuel Stone of Hartford no more tersely than truly put it, this kind of Congregationalism was simply a ‘speaking Aristocracy in the face of a silent Democracy.’” [Footnote: Early New England Congregationalism, as seen in its Literature, p. 429. Dr. Dexter.]

It is true that Vassal’s petition was the event which made the ministers decide to call a synod [Footnote: Winthrop, ii. 264.] by means of an invitation of the General Court; but it is also certain that under no circumstances would the meeting of some such council have been long delayed. For sixteen years the well-known process had been going on, of the creation of institutions by custom, having the force of law; the stage of development had now been reached when it was necessary that those usages should take the shape of formal enactments. The Cambridge platform therefore marks the completion of an organization, and as such is the central point in the history of the Puritan Commonwealth. The work was done in August, 1648: the Westminster Confession was promulgated as the creed; the powers of the clergy were minutely defined, and the duty of the laity stated to be “obeying their elders and submitting themselves unto them in the Lord.” [Footnote: Cambridge Platform, ch. x. section 7.] The magistrate was enjoined to punish “idolatry, blasphemy, heresy,” and to coerce any church becoming “schismatical.”

In October, 1649, the court commended the platform to the consideration of the congregations; in October, 1651, it was adopted; and when church and state were thus united by statute the theocracy was complete.

The close of the era of construction is also marked by the death of those two remarkable men whose influence has left the deepest imprint upon the institutions they helped to mould: John Winthrop, who died in 1649, and John Cotton in 1652.

Winthrop’s letters to his wife show him to have been tender and gentle, and that his disposition was one to inspire love is proved by the affection those bore him who had suffered most at his hands. Williams and Vane and Coddington kept their friendship for him to the end. But these very qualities, so amiable in themselves, made him subject to the influence of men of inflexible will. His dream was to create on earth a commonwealth of saints whose joy would be to walk in the ways of God. But in practice he had to deal with the strongest of human passions. In 1634, though supported by Cotton, he was defeated by Dudley, and there can be no doubt that this was caused by the defection of the body of the clergy. The evidence seems conclusive, for the next year Vane brought about an interview between the two at which Haynes was present, and there Haynes upbraided him with remissness in administering justice. [Footnote: Winthrop, i. 178.] Winthrop agreed to leave the question to the ministers, who the next morning gave an emphatic opinion in favor of strict discipline. Thenceforward he was pliant in their hands, and with that day opened the dark epoch of his life. By leading the crusade against the Antinomians he regained the confidence of the elders and they never again failed him; but in return they exacted obedience to their will; and the rancor with which he pursued Anne Hutchinson, Gorton, and Childe cannot be extenuated, and must ever be a stain upon his fame.

As Hutchinson points out, in early life his tendencies were liberal, but in America he steadily grew narrow. The reason is obvious. The leader of an intolerant party has himself to be intolerant. His claim to eminence as a statesman must rest upon the purity of his moral character, his calm temper, and his good judgment; for his mind was not original or brilliant, nor was his thought in advance of his age. Herein he differed from his celebrated contemporary, for among the long list of famous men, who are the pride of Massachusetts, there are few who in mere intellectual capacity outrank Cotton. He was not only a profound scholar, an eloquent preacher, and a famous controversialist, but a great organizer, and a natural politician. He it was who constructed the Congregational hierarchy; his publications were the accepted authority both abroad and at home; and the system which he developed in his books was that which was made law by the Cambridge Platform.

Of medium height, florid complexion, and as he grew old some tendency to be stout, but with snowy hair and much personal dignity, he seems to have had an irresistible charm of manner toward those whom he wished to attract.

Comprehending thoroughly the feelings and prejudices of the clergy, he influenced them even more by his exquisite tact than by his commanding ability; and of easy fortune and hospitable alike from inclination and from interest, he entertained every elder who went to Boston. He understood the art of flattery to perfection; or, as Norton expressed it, “he was a man of ingenuous and pious candor, rejoicing (as opportunity served) to take notice of and testifie unto the gifts of God in his brethren, thereby drawing the hearts of them to him....” [Footnote: Norton’s Funeral Sermon, p. 37.] No other clergyman has ever been able to reach the position he held with apparent ease, which amounted to a sort of primacy of New England. His dangers lay in the very fecundity of his mind. Though hampered by his education and profession, he was naturally liberal; and his first miscalculation was when, almost immediately on landing, he supported Winthrop, who was in disgrace for the mildness of his administration, against the austerer Dudley.

The consciousness of his intellectual superiority seems to have given him an almost overweening confidence in his ability to induce his brethren to accept the broader theology he loved to preach; nor did he apparently realize that comprehension was incompatible with a theocratic government, and that his success would have undermined the organization he was laboring to perfect. He thus committed the error of his life in undertaking to preach a religious reformation, without having the resolution to face a martyrdom. But when he saw his mistake, the way in which he retrieved himself showed a consummate knowledge of human nature and of the men with whom he had to deal. Nor did he ever forget the lesson. From that time forward he took care that no one should be able to pick a flaw in his orthodoxy; and whatever he may have thought of much of the policy of his party, he was always ready to defend it without flinching.

Neither he nor Winthrop died too soon, for with the completion of the task of organization the work that suited them was finished, and they were unfit for that which remained to be done. An oligarchy, whose power rests on faith and not on force, can only exist by extirpating all who openly question their pretensions to preeminent sanctity; and neither of these men belonged to the class of natural persecutors,—the one was too gentle, the other too liberal. An example will show better than much argument how little in accord either really was with that spirit which, in the regular course of social development, had thenceforward to dominate over Massachusetts.

Captain Partridge had fought for the Parliament, and reached Boston at the beginning of the winter of 1645. He was arrested and examined as a heretic. The magistrates referred the case to Cotton, who reported that “he found him corrupt in judgment,” but “had good hope to reclaim him.” [Footnote: Winthrop, ii. 251.] An instant recantation was demanded; it was of course refused, and, in spite of all remonstrance, the family was banished in the snow. Winthrop’s sad words were: “But sure, the rule of hospitality to strangers, and of seeking to pluck out of the fire such as there may be hope of, … do seem to require more moderation and indulgence of human infirmity where there appears not obstinacy against the clear truth.” [Footnote: Winthrop, ii. 251.]

But in the savage and bloody struggle that was now at hand there was no place for leaders capable of pity or remorse, and the theocracy found supremely gifted chieftains in John Norton and John Endicott.

Norton approaches the ideal of the sterner orders of the priesthood. A gentleman by birth and breeding, a ripe scholar, with a keen though polished wit, his sombre temper was deeply tinged with fanaticism. Unlike so many of his brethren, temporal concerns were to him of but little moment, for every passion of his gloomy soul was intensely concentrated on the warfare he believed himself waging with the fiend. Doubt or compassion was impossible, for he was commissioned by the Lord. He was Christ’s elected minister, and misbelievers were children of the devil whom it was his sacred duty to destroy. He knew by the Word of God that all save the orthodox were lost, and that heretics not only perished, but were the hirelings of Satan, who tempted the innocent to their doom; he therefore hated and feared them more than robbers or murderers. Words seemed to fail him when he tried to express his horror: “The face of death, the King of Terrours, the living man by instinct turneth his face from. An unusual shape, a satanical phantasm, a ghost, or apparition, affrights the disciples. But the face of heresie is of a more horrid aspect than all … put together, as arguing some signal inlargement of the power of darkness as being diabolical, prodigeous, portentous.” [Footnote: Heart of New Eng. Rent, p. 46.] By nature, moreover, he had in their fullest measure the three attributes of a preacher of a persecution,—eloquence, resolution, and a heart callous to human suffering. To this formidable churchman was joined a no less formidable magistrate.

No figure in our early history looms out of the past like Endicott’s. The harsh face still looks down from under the black skull-cap, the gray moustache and pointed beard shading the determined mouth, but throwing into relief the lines of the massive jaw. He is almost heroic in his ferocious bigotry and daring,—a perfect champion of the church.

The grim Puritan soldier is almost visible as, standing at the head of his men, he tears the red cross from the flag, and defies the power of England; or, in that tremendous moment, when the people were hanging breathless on the fate of Christison, when insurrection seemed bursting out beneath his feet, and his judges shrunk aghast before the peril, we yet hear the savage old man furiously strike the table, and, thanking God that he at least dares to do his duty, we see him rise alone before that threatening multitude to condemn the heretic to death.

CHAPTER IV. – THE ANABAPTISTS

The Rev. Thomas Shepard, pastor of Charlestown, was such an example, “in word, in conversation, in civility, in spirit, in faith, in purity, that he did let no man despise his youth;” [Footnote: Magnalia, bk. 4, ch. ix. Section 6.] and yet, preaching an election sermon before the governor and magistrates, he told them that “anabaptisme … hath ever been lookt at by the godly leaders of this people as a scab.” [Footnote: Eye Salve, p. 24.] While the Rev. Samuel Willard, president of Harvard, declared that “such a rough thing as a New England Anabaptist is not to be handled over tenderly.” [Footnote: Ne Sutor, p. 10.]

So early as 1644, therefore, the General Court “Ordered and agreed, yt if any person or persons within ye iurisdiction shall either openly condemne or oppose ye baptizing of infants, or go about secretly to seduce others from ye app’bation or use thereof, or shall purposely depart ye congregation at ye administration of ye ordinance, … and shall appear to ye Co’t willfully and obstinately to continue therein after due time and meanes of conviction, every such person or persons shallbe sentenced to banishment.” [Footnote: Mass. Rec. ii. 85. 13 November, 1644.]

The legislation, however, was unpopular, for Winthrop relates that in October, 1645, divers merchants and others petitioned to have the act repealed, because of the offense taken thereat by the godly in England, and the court seemed inclined to accede, “but many of the elders … entreated that the law might continue still in force, and the execution of it not suspended, though they disliked not that all lenity and patience should be used for convincing and reclaiming such erroneous persons. Whereupon the court refused to make any further order.” [Footnote: Winthrop, ii. 251.] And Edward Winslow assured Parliament in 1646, when sent to England to represent the colony, that, some mitigation being desired, “it was answered in my hearing. ‘T is true we have a severe law, but wee never did or will execute the rigor of it upon any.... But the reason wherefore wee are loath either to repeale or alter the law is, because wee would have it … to beare witnesse against their judgment, … which we conceive … to bee erroneous.” [Footnote: Hypocrisie Unmasked, 101.]

Unquestionably, at that time no one had been banished; but in 1644 “one Painter, for refusing to let his child be baptized, … was brought before the court, where he declared their baptism to be anti-Christian. He was sentenced to be whipped, which he bore without flinching, and boasted that God had assisted him.” [Footnote: Hutch. Hist. i. 208, note.] Nor was his a solitary instance of severity. Yet, notwithstanding the scorn and hatred which the orthodox divines felt for these sectaries, many very eminent Puritans fell into the errors of that persuasion. Roger Williams was a Baptist, and Henry Dunster, for the same heresy, was removed from the presidency of Harvard, and found it prudent to end his days within the Plymouth jurisdiction. Even that great champion of infant baptism, Jonathan Mitchell, when thrown into intimate relations with Dunster, had doubts.

“That day … after I came from him I had a strange experience; I found hurrying and pressing suggestions against Pædobaptism, and injected scruples and thoughts whether the other way might not be right, and infant baptism an invention of men; and whether I might with good conscience baptize children and the like. And these thoughts were darted in with some impression, and left a strange confusion and sickliness upon my spirit. Yet, methought, it was not hard to discern that they were from the Evil One; … And it made me fearful to go needlessly to Mr. D.; for methought I found a venom and poison in his insinuations and discourses against Pædobaptism.” [Footnote: Magnalia, bk. 4, ch. iv. Section 10.]

Henry Dunster was an uncommon man. Famed for piety in an age of fanaticism, learned, modest, and brave, by the unremitting toil of thirteen years he raised Harvard from a school to the position which it has since held; and though very poor, and starving on a wretched and ill-paid pittance, he gave his beloved college one hundred acres of land at the moment of its sorest need. [Footnote: Quincy’s History of Harvard, i. 15.] Yet he was a criminal, for he would not baptize infants, and he met with the “lenity and patience” which the elders were not unwilling should be used toward the erring.

He was indicted and convicted of disturbing church ordinances, and deprived of his office in October, 1654. He asked for leave to stay in the house he had built for a few months, and his petition in November ought to be read to understand how heretics were made to suffer:—

“1st. The time of the year is unseasonable, being now very near the shortest day, and the depth of winter.

“2d. The place unto which I go is unknown to me and my family, and the ways and means of subsistance....

“3d. The place from which I go hath fire, fuel, and all provisions for man and beast, laid in for the winter.... The house I have builded upon very damageful conditions to myself, out of love for the college, taking country pay in lieu of bills of exchange on England, or the house would not have been built....

“4th. The persons, all beside myself, are women and children, on whom little help, now their minds lie under the actual stroke of affliction and grief. My wife is sick, and my youngest child extremely so, and hath been for months, so that we dare not carry him out of doors, yet much worse now than before.... Myself will willingly bow my neck to any yoke of personal denial, for I know for what and for whom, by grace I suffer.” [Footnote: History of Harvard, i. 18.]

He had before asked Winthrop to cause the government to pay him what it owed, and he ended his prayer in these words: “Considering the poverty of the country, I am willing to descend to the lowest step; and if nothing can comfortably be allowed, I sit still appeased; desiring nothing more than to supply me and mine with food and raiment.” [Footnote: Idem, i. 20.] He received that mercy which the church has ever shown to those who wander from her fold; he was given till March, and then, with dues unpaid, was driven forth a broken man, to die in poverty and neglect.

But Jonathan Mitchell, pondering deeply upon the wages he saw paid at his very hearthstone, to the sin of his miserable old friend, snatched his own soul from Satan’s jaws. And thenceforward his path lay in pleasant places, and he prospered exceedingly in the world, so that “of extream lean he grew extream fat; and at last, in an extream hot season, a fever arrested him, just after he had been preaching.... Wonderful were the lamentations which this deplorable death fill’d the churches of New England withal.... Yea … all New England shook when that pillar fell to the ground.” [Footnote: Magnalia, bk. 4, ch. iv. Section 16.]

Notwithstanding, therefore, clerical promises of gentleness, Massachusetts was not a comfortable place of residence for Baptists, who, for the most part, went to Rhode Island; and John Clark [Footnote: For sketch of Clark’s life see Allen’s Biographical Dictionary.] became the pastor of the church which they formed at Newport about 1644. He had been born about 1610, and had been educated in London as a physician. In 1637 he landed at Boston, where he seems to have become embroiled in the Antinomian controversy; at all events, he fared so ill that, with several others, he left Massachusetts ‘resolving, through the help of Christ, to get clear of all [chartered companies] and be of ourselves.’ In the course of their wanderings they fell in with Williams, and settled near him.