полная версия

полная версияBones

"But it is you, O my lord," said Bosambo, extravagantly, "who asks this question. You, who have suddenly come amongst us and who are brighter to us than the moon and dearer to us than the land which grows corn; therefore must I speak to you that which is in my heart. If I lie, strike me down at your feet, for I am ready to die."

He paused again, throwing out his arms invitingly, but Bones said nothing.

"Now this I tell you," Bosambo shook his finger impressively, "that the N'bosini lives."

"Where?" asked Bones, quickly.

Already he saw himself lecturing before a crowded audience at the Royal Geographical Society, his name in the papers, perhaps a Tibbett River or a Francis Augustus Mountain added to the sum of geographical knowledge.

"It is in a certain place," said Bosambo, solemnly, "which only I know, and I have sworn a solemn oath by many sacred things which I dare not break, by letting of blood and by rubbing in of salt, that I will not divulge the secret."

"O, tell me, Bosambo," demanded Bones, leaning forward and speaking rapidly, "what manner of people are they who live in the city of N'bosini?"

"They are men and women," said Bosambo after a pause.

"White or black?" asked Bones, eagerly.

Bosambo thought a little.

"White," he said soberly, and was immensely pleased at the impression he created.

"I thought so," said Bones, excitedly, and jumped up, his eyes wider than ever, his hands trembling as he pulled his note-book from his breast pocket.

"I will make a book3 of this, Bosambo," he said, almost incoherently. "You shall speak slowly, telling me all things, for I must write in English."

He produced his pencil, squatted again, open book upon his knee, and looked up at Bosambo to commence.

"Lord, I cannot do this," said Bosambo, his face heavy with gloom, "for have I not told your lordship that I have sworn such oath? Moreover," he said carelessly, "we who know the secret, have each hidden a large bag of silver in the ground, all in one place, and we have sworn that he who tells the secret shall lose his share. Now, by the Prophet, 'Eye-of-the-Moon' (this was one of the names which Bones had earned, for which his monocle was responsible), I cannot do this thing."

"How large was this bag, Bosambo?" asked Bones, nibbling the end of his pencil.

"Lord, it was so large," said Bosambo.

He moved his hands outward slowly, keeping his eyes fixed upon Lieutenant Tibbetts till he read in them a hint of pain and dismay. Then he stopped.

"So large," he said, choosing the dimensions his hands had indicated before Bones showed signs of alarm. "Lord, in the bag was silver worth a hundred English pounds."

Bones, continuing his meal of cedar-wood, thought the matter out.

It was worth it.

"Is it a large city?" he asked suddenly.

"Larger than the whole of the Ochori," answered Bosambo impressively.

"And tell me this, Bosambo, what manner of houses are these which stand in the city of the N'bosini?"

"Larger than kings' huts," said Bosambo.

"Of stone?"

"Lord, of rock, so that they are like mountains," replied Bosambo.

Bones shut his book and got up.

"This day I go back to M'ilitani, carrying word of the N'bosini," said he, and Bosambo's jaw dropped, though Bones did not notice the fact.

"Presently I will return, bringing with me silver of the value of a hundred English pounds, and you shall lead us to this strange city."

"Lord, it is a far way," faltered Bosambo, "across many swamps and over high mountains; also there is much sickness and death, wild beasts in the forests and snakes in the trees and terrible storms of rain."

"Nevertheless, I will go," said Bones, in high spirits, "I, and you also."

"Master," said the agitated Bosambo, "say no word of this to M'ilitani; if you do, be sure that my enemies will discover it and I shall be killed."

Bones hesitated and Bosambo pushed his advantage.

"Rather, lord," said he, "give me all the silver you have and let me go alone, carrying a message to the mighty chief of the N'bosini. Presently I will return, bringing with me strange news, such as no white lord, not even Sandi, has received or heard, and cunning weapons which only N'bosini use and strange magics. Also will I bring you stories of their river, but I will go alone, though I die, for what am I that I should deny myself from the service of your lordship?"

It happened that Bones had some twenty pounds on the Zaire, and Bosambo condescended to come aboard to accept, with outstretched hands, this earnest of his master's faith.

"Lord," said he, solemnly, as he took a farewell of his benefactor, "though I lose a great bag of silver because I have betrayed certain men, yet I know that, upon a day to come, you will pay me all that I desire. Go in peace."

It was a hilarious, joyous, industrious Bones who went down the river to headquarters, occupying his time in writing diligently upon large sheets of foolscap in his no less large unformed handwriting, setting forth all that Bosambo had told him, and all the conclusions he might infer from the confidence of the Ochori king.

He was bursting with his news. At first, he had to satisfy his chief that he had carried out his orders.

Fortunately, Hamilton needed little convincing; his own spies had told him of the quietening down of certain truculent sections of his unruly community and he was prepared to give his subordinate all the credit that was due to him.

It was after dinner and the inevitable rice pudding had been removed and the pipes were puffing bluely in the big room of the Residency, when Bones unburdened himself.

"Sir," he began, "you think I am an ass."

"I was not thinking so at this particular moment," said Hamilton; "but, as a general consensus of my opinion concerning you, I have no fault to find with it."

"You think poor old Bones is a goop," said Lieutenant Tibbetts with a pitying smile, "and yet the name of poor old Bones is going down to posterity, sir."

"That is posterity's look-out," said Hamilton, offensively; but Bones ignored the rudeness.

"You also imagine that there is no such land as the N'bosini, I think?"

Bones put the question with a certain insolent assurance which was very irritating.

"I not only think, but I know," replied Hamilton.

Bones laughed, a sardonic, knowing laugh.

"We shall see," he said, mysteriously; "I hope, in the course of a few weeks, to place a document in your possession that will not only surprise, but which, I believe, knowing that beneath a somewhat uncouth manner lies a kindly heart, will also please you."

"Are you chucking up the army?" asked Hamilton with interest.

"I have no more to say, sir," said Bones.

He got up, took his helmet from a peg on the wall, saluted and walked stiffly from the Residency and was swallowed up in the darkness of the parade ground.

A quarter of an hour later, there came a tap upon his door and Mahomet Ali, his sergeant, entered.

"Ah, Mah'met," said Hamilton, looking up with a smile, "all things were quiet on the river my lord Tibbetts tells me."

"Lord, everything was proper," said the sergeant, "and all people came to palaver humbly."

"What seek you now?" asked Hamilton.

"Lord," said Mahomet, "Bosambo of the Ochori is, as you know, of my faith, and by certain oaths we are as blood brothers. This happened after a battle in the year of Drought when Bosambo saved my life."

"All this I know," said Hamilton.

"Now, lord," said Mahomet Ali, "I bring you this."

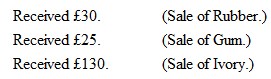

He took from the inside of his uniform jacket a little canvas bag, opened it slowly and emptied its golden contents upon the table. There was a small shining heap of sovereigns and a twisted note; this latter he placed in Hamilton's hand and the Houssa captain unfolded it. It was a letter in Arabic in Bosambo's characteristic and angular handwriting.

"From Bosambo, the servant of the Prophet, of the upper river in the city of the Ochori, to M'ilitani, his master. Peace on your house.

"In the name of God I send you this news. My lord with the moon-eye, making inquiries about the N'bosini, came to the Ochori and I told him much that he wrote down in a book. Now, I tell you, M'ilitani, that I am not to blame, because my lord with the moon-eye wrote down these things. Also he gave me twenty English pounds because I told him certain stories and this I send to you, that you shall put it in with my other treasures, making a mark in your book that this twenty pounds is the money of Bosambo of the Ochori, and that you will send me a book, saying that this money has come to you and is safely in your hands. Peace and felicity upon your house.

"Written in my city of Ochori and given to my brother, Mahomet Ali, who shall carry it to M'ilitani at the mouth of the river."

"Poor old Bones!" said Hamilton, as he slowly counted the money. "Poor old Bones!" he repeated.

He took an account book from his desk and opened it at a page marked "Bosambo." His entry was significant.

To a long list of credits which ran:

he added:

CHAPTER IV

THE FETISH STICK

I

N'gori the Chief had a son who limped and lived. This was a marvellous thing in a land where cripples are severely discouraged and malformity is a sure passport for heaven.

The truth is that M'fosa was born in a fishing village at a period of time when all the energies of the Akasava were devoted to checking and defeating the predatory raidings of the N'gombi, under that warlike chief G'osimalino, who also kept other nations on the defensive, and held the river basin, from the White River, by the old king's territory, to as far south as the islands of the Lesser Isisi.

When M'fosa was three months old, Sanders had come with a force of soldiers, had hanged G'osimalino to a high tree, had burnt his villages and destroyed his crops and driven the remnants of his one-time invincible army to the little known recesses of the Itusi Forest.

Those were the days of the Cakitas or government chiefs, and it was under the beneficent sway of one of these that M'fosa grew to manhood, though many attempts were made to lure him to unfrequented waterways and blind crocodile creeks where a lame man might be lost, and no one be any the wiser.

Chief of the eugenists was Kobolo, the boy's uncle, and N'gori's own brother. This dissatisfied man, with several of M'fosa's cousins, once partially succeeded in kidnapping the lame boy, and they were on their way to certain middle islands in the broads of the river to accomplish their scheme—which was to put out the eyes of M'fosa and leave him to die—when Sanders had happened along.

He it was who set all the men of M'fosa's village to cut down a high pine tree—at an infernal distance from the village, and had men working for a week, trimming and planing that pine; and another week they spent carrying the long stem through the forest (Sanders had devilishly chosen his tree in the most inaccessible part of the woods), and yet another week digging large holes and erecting it.

For he was a difficult man to please. Broad backs ran sweat to pull and push and hoist that great flagstaff (as it appeared with its strong pulley and smooth sides) to its place. And no sooner was it up than my lord Sandi had changed his mind and must have it in another place. Sanders would come back at intervals to see how the work was progressing. At last it was fixed, that monstrous pole, and the men of the village sighed thankfully.

"Lord, tell me," N'gori had asked, "why you put this great stick in the ground?"

"This," said Sanders, "is for him who injures M'fosa your son; upon this will I hang him. And if there be more men than one who take to the work of slaughter, behold! I will have yet another tree cut and hauled, and put in a place and upon that will I hang the other man. All men shall know this sign, the high stick as my fetish; and it shall watch the evil hearts and carry me all thoughts, good and evil. And then I tell you, that such is its magic, that if needs be, it shall draw me from the end of the world to punish wrong."

This is the story of the fetish stick of the Akasava and of how it came to be in its place.

None did hurt to M'fosa, and he grew to be a man, and as he grew and his father became first counsellor, then petty chief, and, at last, paramount chief of the nation, M'fosa developed in hauteur and bitterness, for this high pole rainwashed, and sun-burnt, was a reminder, not of the strong hand that had been stretched out to save him, but of his own infirmity.

And he came to hate it, and by some curious perversion to hate the man who had set it up.

Most curious of all to certain minds, he was the first of those who condemned, and secretly slew, the unfortunates, who either came into the world hampered by disfigurement, or who, by accident, were unfitted for the great battle.

He it was who drowned Kibusi the woodman, who lost three fingers by the slipping of the axe; he was the leader of the young men who fell upon the boy Sandilo-M'goma, who was crippled by fire; and though the fetish stood a menace to all, reading thoughts and clothed with authority, yet M'fosa defied spirits and went about his work reckless of consequence.

When Sanders had gone home, and it seemed that law had ceased to be, N'gori (as I have shown) became of a sudden a bold and fearless man, furbished up his ancient grievances and might have brought trouble to the land, but for a watchful Bosambo.

This is certain, however, that N'gori himself was a good-enough man at heart, and if there was evil in his actions be sure that behind him prompting, whispering, subtly threatening him, was his malignant son, a sinister figure with one eye half closed, and a figure that went limping through the city with a twisted smile.

An envoy came to the Ochori country bearing green branches of the Isisi palm, which signifies peace, and at the head of the mission—for mission it was—came M'fosa.

"Lord Bosambo," said the man who limped, "N'gori the chief, my father, has sent me, for he desires your friendship and help; also your loving countenance at his great feast."

"Oh, oh!" said Bosambo, drily, "what king's feast is this?"

"Lord," rejoined the other, "it is no king's feast, but a great dance of rejoicing, for our crops are very plentiful, and our goats have multiplied more than a man can count; therefore my father said: Go you to Bosambo of the Ochori, he who was once my enemy and now indeed my friend. And say to him 'Come into my city, that I may honour you.'"

Bosambo thought.

"How can your lord and father feast so many as I would bring?" he asked thoughtfully, as he sat, chin on palm, pondering the invitation, "for I have a thousand spearmen, all young men and fond of food."

M'fosa's face fell.

"Yet, Lord Bosambo," said he, "if you come without your spearmen, but with your counsellors only–"

Bosambo looked at the limper, through half-closed eyes. "I carry spears to a Dance of Rejoicing," he said significantly, "else I would not Dance or Rejoice."

M'fosa showed his teeth, and his eyes were filled with hateful fires. He left the Ochori with bad grace, and was lucky to leave it at all, for certain men of the country, whom he had put to torture (having captured them fishing in unauthorized waters), would have rushed him but for Bosambo's presence.

His other invitation was more successful. Hamilton of the Houssas was at the Isisi city when the deputation called upon him.

"Here's a chance for you, Bones," he said.

Lieutenant Tibbetts had spent a vain day, fishing in the river with a rod and line, and was sprawling under a deck-chair under the awning of the bridge.

"Would you like to be the guest of honour at N'gori's little thanksgiving service?"

Bones sat up.

"Shall I have to make a speech?" he asked cautiously.

"You may have to respond for the ladies," said Hamilton. "No, my dear chap, all you will have to do will be to sit round and look clever."

Bones thought awhile.

"I'll bet you're putting me on to a rotten job," he accused, "but I'll go."

"I wish you would," said Hamilton, seriously. "I can't get the hang of M'fosa's mind, ever since you treated him with such leniency."

"If you're goin' to dig up the grisly past, dear old sir," said a reproachful Bones, "if you insist recalling events which I hoped, sir, were hidden in oblivion, I'm going to bed."

He got up, this lank youth, fixed his eyeglass firmly and glared at his superior.

"Sit down and shut up," said Hamilton, testily; "I'm not blaming you. And I'm not blaming N'gori. It's that son of his—listen to this."

He beckoned the three men who had come down from the Akasava as bearers of the invitation.

"Say again what your master desires," he said.

"Thus speaks N'gori, and I talk with his voice," said the spokesman, "that you shall cut down the devil-stick which Sandi planted in our midst, for it brings shame to us, and also to M'fosa the son of our master."

"How may I do this?" asked Hamilton, "I, who am but the servant of Sandi? For I remember well that he put the stick there to make a great magic."

"Now the magic is made," said the sullen headman; "for none of our people have died the death since Sandi set it up."

"And dashed lucky you've been," murmured Bones.

"Go back to your master and tell him this," said Hamilton. "Thus says M'ilitani, my lord Tibbetti will come on your feast day and you shall honour him; as for the stick, it stands till Sandi says it shall not stand. The palaver is finished."

He paced up and down the deck when the men had gone, his hands behind him, his brows knit in worry.

"Four times have I been asked to cut down Sanders' pole," he mused aloud. "I wonder what the idea is?"

"The idea?" said Bones, "the idea, my dear old silly old fellow, isn't it as plain as your dashed old nose? They don't want it!"

Hamilton looked down at him.

"What a brain you must have, Bones!" he said admiringly. "I often wonder you don't employ it."

II

By the Blue Pool in the forest there is a famous tree gifted with certain properties. It is known in the vernacular of the land, and I translate it literally, "The-tree-that-has-no-echo-and-eats-up-sound." Men believe that all that is uttered beneath its twisted branches may be remembered, but not repeated, and if one shouts in its deadening shade, even they who stand no farther than a stride from its furthermost stretch of branch or leaf, will hear nothing.

Therefore is the Silent Tree much in favour for secret palaver, such as N'gori and his limping son attended, and such as the Lesser Isisi came to fearfully.

N'gori, who might be expected to take a very leading part in the discussion which followed the meeting, was, in fact, the most timorous of those who squatted in the shadow of the huge cedar.

Full of reservations, cautions, doubts and counsels of discretion was N'gori till his son turned on him, grinning as his wont when in his least pleasant mood.

"O, my father," said he softly, "they say on the river that men who die swiftly say no more than 'wait' with their last breath; now I tell you that all my young men who plot secretly with me, are for chopping you—but because I am like a god to them, they spare you."

"My son," said N'gori uneasily, "this is a very high palaver, for many chiefs have risen and struck at the Government, and always Sandi has come with his soldiers, and there have been backs that have been sore for the space of a moon, and necks that have been sore for this time," he snapped finger, "and then have been sore no more."

"Sandi has gone," said M'fosa.

"Yet his fetish stands," insisted the old man; "all day and all night his dreadful spirit watches us; for this we have all seen that the very lightnings of M'shimba M'shamba run up that stick and do it no harm. Also M'ilitani and Moon-in-the-Eye–"

"They are fools," a counsellor broke in.

"Lord M'ilitani is no fool, this I know," interrupted a fourth.

"Tibbetti comes—and brings no soldiers. Now I tell you my mind that Sandi's fetish is dead—as Sandi has passed from us, and this is the sign I desire—I and my young men. We shall make a killing palaver in the face of the killing stick, and if Sandi lives and has not lied to us, he shall come from the end of the world as he said."

He rose up from the ground. There was no doubt now who ruled the Akasava.

"The palaver is finished," he said, and led the way back to the city, his father meekly following in the rear.

Two days later Bones arrived at the city of the Akasava, bringing with him no greater protection than a Houssa orderly afforded.

III

On a certain night in September Mr. Commissioner Sanders was the guest of the Colonial Secretary at his country seat in Berkshire.

Sanders, who was no society man, either by training or by inclination, would have preferred wandering aimlessly about the brilliantly lighted streets of London, but the engagement was a long-standing one. In a sense he was a lion against his will. His name was known, people had written of his character and his sayings; he had even, to his own amazement, delivered a lecture before the members of the Ethnological Society on "Native Folk-lore," and had emerged from the ordeal triumphantly. The guests of Lord Castleberry found Sanders a shy, silent man who could not be induced to talk of the land he loved so dearly. They might have voted him a bore, but for the fact that he so completely effaced himself they had little opportunity for forming so definite a judgment.

It was on the second night of his visit to Newbury Grange that they had cornered him in the billiard-room. It was the beautiful daughter of Lord Castleberry who, with the audacity of youth, forced him, metaphorically speaking, into a corner, from whence there was no escape.

"We've been very patient, Mr. Sanders," she pouted; "we are all dying to hear of your wonderful country, and Bosambo, and fetishes and things, and you haven't said a word."

"There is little to say," he smiled; "perhaps if I told you—something about fetishes…?"

There was a chorus of approval.

Sanders had gained enough courage from his experience before the Ethnological Society, and began to talk.

"Wait," said Lady Betty; "let's have all these glaring lights out—they limit our imagination."

There was a click, and, save for one bracket light behind Sanders, the room was in darkness. He was grateful to the girl, and well rewarded her and the party that sat round on chairs, on benches around the edge of the billiard-table, listening. He told them stories … curious, unbelievable; of ghost palavers, of strange rites, of mysterious messages carried across the great space of forests.

"Tell us about fetishes," said the girl's voice.

Sanders smiled. There rose to his eyes the spectacle of a hot and weary people bringing in a giant tree through the forest, inch by inch.

And he told the story of the fetish of the Akasava.

"And I said," he concluded, "that I would come from the end of the world–"

He stopped suddenly and stared straight ahead. In the faint light they saw him stiffen like a setter.

"What is wrong?"

Lord Castleberry was on his feet, and somebody clicked on the lights.

But Sanders did not notice.

He was looking towards the end of the room, and his face was set and hard.

"O, M'fosa," he snarled, "O, dog!"

They heard the strange staccato of the Bomongo tongue and wondered.

Lieutenant Tibbetts, helmetless, his coat torn, his lip bleeding, offered no resistance when they strapped him to the smooth high pole. Almost at his feet lay the dead Houssa orderly whom M'fosa had struck down from behind.

In a wide circle, their faces half revealed by the crackling fire which burnt in the centre, the people of the Akasava city looked on impressively.

N'gori, the chief, his brows all wrinkled in terror, his shaking hands at his mouth in a gesture of fear, was no more than a spectator, for his masterful son limped from side to side, consulting his counsellors.