полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 61, No. 378, April, 1847

It is curious to see the enormous size to which the silver-fir will here attain. Sometimes this tree rises with the utmost regularity—sending out its branches at equal intervals, tier above tier—itself tapering upwards, and each circle of branches decreasing in diameter until a hundred and fifty feet are gained. The stems of some of these giants of the forest are eighteen feet in circumference at the height of a man from the ground, and their lower branches would of themselves form trees such as many a trim and well-kept park could never boast of. At other times the original tree will have met with an accidental fracture when young, and after going up twenty or thirty feet from the ground, as an immense wooden column, will throw out three or four other trees from its summit, which will all shoot up parallel to each other into the air and form a little forest of themselves. Very frequently, however, it happens that the tree has been contorted in its early growth, and then broken afterwards: in such cases it seems to have forgotten its nature completely, and to have gone mad in its spirit of increase; for it turns and forces itself into the strangest convolutions and intricacies of form. It becomes like a short stunted oak, or a thickly knotted thorn: or it might sometimes be mistaken for a willow, at others for a cedar—for any thing but one of the same species as the stately spire of wood that soars up into the heaven close by its side.

When the tree becomes quite dead, blasted by lightning, or injured by the attacks of animals at its base, it does not therefore lose all its beauty; for it becomes immediately covered with a peculiar gray lichen of great length and luxuriance; occupying every branch and twig of the dead tree, and clothing it, as it were, with a second but a new kind of foliage. This lichen will sometimes hang down from the branches in strings of weeping vegetation to the length of five feet and more. You may sometimes ride under the living tree where this parasitical foliage is mixed with the real covering of the boughs, forming the most anomalous, and yet the most picturesque of contrasts.

In forests of this kind, the undergrowth of brushwood of every variety is exceedingly abundant and beautiful: every woodland shrub is to be found there—the hazel especially—and the thickets thereby formed are quite impenetrable. As the older and larger trees decay, they lose their footing in the soil, and fall in every variety of strange position—presenting a picture of desolation, the effect of which is at first strange to the mind, and at last becomes even painful. But wherever a tree falls, there a luxuriant growth of moss succeeds: a little peat-bed forms itself underneath: generations after generations of mosses and watery plants succeed one another; and in time the prostrate trunk is entirely buried under a bright-green bed, soft as down, but treacherous to the foot as a quicksand. Often may the wanderer amid these wild glades think to throw himself on one of these inviting couches; and, bounding on to it, he sinks five or six feet through moss and weed and dirty peat, till his descent is stopped by the skeleton of the vast tree that lies beneath. Wild flowers grow all around: and every spot of ground that will produce them is covered in the summer season with the tempting little red strawberry, or the wild raspberry, or the blushing rose. Above all, still keep peering, in solemn and interminable array, the vast monarchs of the wood, the stately and elegant silver-firs.

When you attempt to leave the forests and advance towards the upper grounds, you commonly find yourself stopped by a precipitous wall of basaltic columns, ranging from sixty to seventy feet in height in one unbroken shaft, and forming a vast barrier for miles and miles in length. In some places, these gray basaltic walls come circling round, and constitute an immense natural theatre, sombre and grand as the forest itself. No sound is there heard save the dashing of a distant cascade, or the wind in deep symphony rushing through the slow-waving tops of the trees. Below is a carpet of the most lively green, variegated with turfs of wild flowers and fruits—one of nature's secret, yet choicest gardens. Through the midst trickles a silvery stream, coming you know not whence, but musical in its course, and soon losing itself in the thick underwood that borders the spot all around. Such is the Salle de Mirabeau—one of the loveliest of the many lovely hiding-places of these sublime forests.

The feathered tenants of these woods are mostly birds of prey, or at all events such as the raven, the jay, the pie, and others which can either defend themselves against, or escape from, the falcons that consider these solitudes as their own especial domains. The voices of few singing-birds are to be heard; they have taken refuge nearer the habitations of man: but the hooting of the owl, the beating of the woodpecker, and the screaming of kites and hawks, are all the living sounds that proceed here from the air. Red-deer, wolves, wild-boars, roebucks, and foxes, are the denizens of these forests and these mountains: there is room here for them all to live at their ease; and they abound. No one with a good barrel and a sure aim, ever entered these forests in vain: his burden is commonly more than he can carry home. It is in fact a glorious country for the sportsman; for the lower ranges of the hills abound in hares, the cultivated grounds have plenty of partridges and quails, and the forests are tenanted as has been seen. He who can content himself with his gun or his rod—for the streams are full of trout—may here pass a golden age, without a thought for the morrow, without a desire unfulfilled.

Certainly, if I wished to retire from the world and lead a life of philosophic indifference, not altogether out of the reach of society when I wanted it, these hills and these forests of Auvergne, and the Mont Dor, would be the spots I should select. The mind here would become attuned to the grand harmonies of nature's own making; here, philosophy might be cultivated in good earnest; here, books might be studied and theories digested, without interruption and with inward profit. Here, a man might cultivate both science and art, and he might become again the free and happy being which, until he betook himself to congregating in towns, he was destined to be. Yes! when I do withdraw from this world's vanities and troubles, give me forests and mountains like those of Mont Dor.

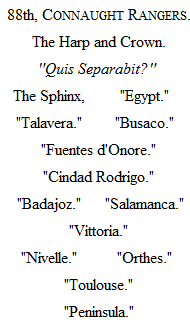

THE FIGHTING EIGHTY-EIGHTH.3

The pugnacity of Irishmen has grown into a proverb, until, in the belief of many, a genuine Milesian is never at peace but when fighting. With certain nations, certain habits are inseparably associated as peculiarly characterising them. Thus, in vulgar apprehension, the Frenchman dances, the German smokes, the Spaniard serenades; and on all hands it is agreed that the Irishman fights. Naturally bellicose, his practice is pugnacious: antagonism is his salient and distinctive quality. Born in a squabble, he dies in a shindy: in his cradle he squeals a challenge; his latest groan is a sound of defiance. Pike and pistol are manifest in his well-developed bump of combativeness; his name is fight, there can be no mistake about it. From highest to lowest—in the peer and the bog-trotter, the inherent propensity breaks forth, more or less modified by station and education.

Be its expression parliamentary or popular, in Donnybrook or St Stephen's, out it will. "Show me the man who'll tread on my coat!" shouts ragged Pat, flourishing his shillelagh as he hurls his dilapidated garment on the shebeen-house floor. From his seat in the senate, a joint of the "Tail" intimates, in more polished but equally intelligible phrase, his inclination for a turn upon the turf. Wherever blows are rife, Hibernia's sons appear; in big fights or little wars the shamrock gleams in the van. No matter the cloth, so long as the quarrel be there. In Austrian white, or Spanish yellow, or Prussian blue,—even in the blood-coloured breeks of Gallia's legions, but especially, and preferred above all, in the "old red rag" of the British grenadier, have Irishmen displayed their valour. And on the list of heroes whom the Green Isle has produced, a proud and prominent place is justly held by that gallant corps, the Rangers of Connaught.

Those of our civilian readers to whom the word "Ranger" is more suggestive of bushes and kangaroos, or of London parks and princes of the blood, than of parades and battle-fields, are referred to page 49 of the Army List. They will there find something to the following effect:—

There is a forest of well-won laurels in this dozen of names. They form a proud blazon for any corps, and one that might satisfy the most covetous of honour. But of all men in the world, old soldiers are the hardest to content. They are patented grumblers. Napoleon knew it, and christened his vieille garde his grognards: tough and true as steel, they yet would have their growl. Now the lads of the Eighty-Eighth, having proved themselves better men even than the veteran guards of the Corsican corporal, also claim the grumbler's privilege, setting forth sundry griefs and grave causes of complaint. They are not allowed the word "Pyrenees" upon their colours, although, at the fight of that name, they not only were present, but rendered good service:—whilst for Waterloo many a man got a medal who, during the whole battle, was scarce within boom of cannon. During more than four years of long marches, short commons, severe hardships, and frequent fighting, the general commanding the third division—the fighting division, as it was called—viewed the Connaughters with dislike, even stigmatised them as confirmed marauders, and recommended none of their officers for promotion, although many greatly distinguished themselves, and some,—the brave Mackie, at Ciudad Rodrigo, for instance—successfully led forlorn-hopes. Finally, passing over the old sore of non-decoration for Peninsular services, since that, common to many regiments, is at last about to be healed,—Mr Robinson, the biographer of Sir Thomas Picton, has dared, in order to vindicate the harsh and partial conduct of his hero, to cast dust upon the facings of the brave boys of Connaught. It need hardly be said that they have found defenders. Of these, the most recent is Lieutenant Grattan, formerly an officer of the Eighty-eighth, and who, after making a vigorous stand, in the pages of a military periodical, against the calumniators of his old corps, has brought up his reserves and come to its support in a book of his own. His volumes, however, are not devoted to mere controversy. He has understood that he should best state the case, establish the merits, and confound the enemies of his regiment, by a faithful narrative of his and its adventures, triumphs, and sufferings. Thus, whilst he has seized the opportunity to deal out some hard knocks to those who have blamed the conduct (none have ever impugned the courage) of the Connaught Rangers, he has produced an entertaining book, thoroughly Irish in character, where the ludicrous and the horrible, the rollicking and the slaughtering, mingle and alternate. Even when most indignant, good humour and a love of fun peep through his pages. His prologue or preamble, entitled "An Answer to some attacks in Robinson's Life of Picton," although redolent of "slugs in a sawpit," is full of the national humour. "Frequently," Mr Robinson has asserted, "just before going into battle, it would be found, upon inspection, that one-half of the Eighty-eighth regiment were without ammunition, having acquired a pernicious habit of exchanging the cartridge for aguardiente, and substituting in their places pieces of wood, cut and coloured to resemble them." Such things have been heard of, even in very well-regulated regiments, as the exchange of powder and ball for brandy and other creature comforts; but it is very unlikely that the practice should have prevailed to any thing like the extent here set down, in a British army in active service and under Wellington's command, and the artfully prepared quaker-cartridges increase the improbability of the statement. Lieutenant Grattan scouts the tale as a base fabrication, lashes out in fine style at its propagator, and claims great merit for the officers who taught their men to beat the best troops in the world with timber ammunition. He puts forward a more serious refutation by a string of certificates from men and officers of all ranks who served with him in the Peninsula, and who strenuously repel the charge as a malignant calumny.

It was at the close of the campaign of 1809, that the historian of the Connaught Rangers, then a newly commissioned youngster, joined, within a march of Badajoz, the first battalion of his regiment. The palmy and triumphant days of the British army in the Peninsula could then hardly be said to have begun. True, they had had victories; the hard-earned one of Talavera had been gained only three months previously, but the general aspect of things was gloomy and disheartening. The campaign had been one of much privation and fatigue; rations were insufficient, quarters unhealthy, and Wellington's little army, borne on the muster-rolls as thirty thousand men, was diminished one-third by disease. The Portuguese, who numbered nearly as many, were raw and untried troops, scarce a man of whom had seen fire, and little reliance could be placed upon them. In spite of Lord Wellington's judicious and reiterated warnings, the incompetent and conceited Spanish generals risked repeated engagements, in which their armies—numerous enough, but ill disciplined, ill armed, and half-starved—were crushed and exterminated. The French side of the medal presented a very different picture. Elated by their German victories, their swords yet red with Austrian blood, Napoleon's best troops and ablest marshals hurried southwards, sanguinely anticipating, upon the fields of the Peninsula, an easy continuation of their recent triumphs. Three hundred and sixty thousand men-at-arms—French, Germans, Italians, Poles, even Mamelukes—spread themselves over Spain, occupied her towns, and invested her fortresses. Ninety thousand soldiers, under Massena, "l'enfant chéri de la Victoire," composed the so-called "army of Portugal," intended to expel from that country, if not to annihilate, the English leader and his small but resolute band, who, undismayed, awaited the coming storm. In the ever-memorable lines of Torres Vedras, the legions of Buonaparte met a stern and effectual dike to their torrent of headlong aggression. Upon the happy selection and able defence of those celebrated positions, were based the salvation of the Peninsula and the subsequent glorious progress of the British arms. Whilst referring to them, Mr Grattan seizes the opportunity to enumerate the services rendered by the army in Spain. "The invincible men," he says, "who defended those lines, aided no doubt by Portuguese and Spanish soldiers, afterwards fought for a period of four years, during which time they never suffered one defeat; and from the first commencement of this gigantic war to its final and victorious termination, the Peninsular army fought and won nineteen pitched battles, and innumerable combats; they made or sustained ten sieges, took four great fortresses, twice expelled the French from Portugal, preserved Alicant, Carthagena, Cadiz, and Lisbon; they killed, wounded, and took about two hundred thousand enemies, and the bones of forty thousand British soldiers lie scattered on the plains and mountains of the Peninsula." And thereupon our friend, the Connaughter, bursts out into indignation that warriors who did such deeds, and, on fifteen different occasions received the thanks of parliament, should have been denied a medal for their services. Certainly, when men who went through the whole, or the greater part, of those terrible campaigns, which they began as commissioned officers, are now seen holding no higher than a lieutenant's rank, one cannot but recognise their title to some additional recompense, and marvel that the modest and well-merited badge they claim should so long have been refused them. Mr Grattan puts much of the blame of such refusal at the door of the Duke of Wellington. Not that he is usually a depreciator of his former leader, of whose military genius and great achievements he ever speaks with respect amounting to veneration. But he does not hesitate to accuse him of having sacrificed his old followers and friends to his own vanity, which petty feeling, he maintains, made the Duke desire that the only medal granted for the war against Napoleon, should be given for the only victory in which he beat the Emperor in person. We believe that many Peninsular officers, puzzled to account for the constant and seemingly causeless refusal of the coveted decoration, hold the same opinion with Mr Grattan. We esteem it rather plausible than sound. The names Of Wellington and Waterloo would not the less be immortally associated because a cross bearing those of Peninsula and Pyrenees, or any other appropriate legend, shone upon the breasts of that "old Spanish infantry," of whom the Duke always spoke with affection and esteem, and to whom he unquestionably is mainly indebted for the wealth, honours, and fame which, for more than thirty years, he has tranquilly enjoyed. Moreover, we cannot credit such selfishness on the part of such a man, or believe that he, to whom a grateful sovereign and country decerned every recompense in their power to bestow, would be so thankless to the men to whose sweat and blood he mainly owed his success—to men who bore him, it may truly be said, upon their shoulders, to the highest pinnacle of greatness a British subject can possibly attain. Waterloo concluded the war: its results were immense, the conduct of the troops engaged heroic; but when we compare the amount of glory there gained with the renown accumulated during six years' warfare—a renown undimmed by a single reverse;—still more, when we contrast the dangers and hardships of one short campaign, however brilliant, with those of half-a-dozen long ones crowded with battles and sieges, we must admit that if the victors of La Belle Alliance nobly earned their medal, the veterans of Salamanca and Badajoz, Vittoria and Toulouse, have a threefold claim to a similar reward. They have long been unjustly deprived of it, and now comparatively few remain to receive the tardily-accorded distinction.

The first action to which Mr Grattan refers, as having himself taken share in, is that of Busaco. The name is familiar to every body, but yet, of all the Peninsular battles, it is perhaps the one of which least is generally known. It was not a very bloody fight—the loss in killed and wounded having been barely seven per cent of the numbers engaged; still it was a highly important one, as testing the quality of the Portuguese levies, upon which much depended. Upon the whole, they behaved pretty well, although they committed one or two awkward blunders, and one of their militia regiments took to flight at the first volley fired by their own friends. Mr Grattan does not usually set himself up as a historical authority with respect to battles, except in matters pertaining to his own regiment or brigade, and which came under his own observation. Nevertheless, concerning Busaco, he speaks boldly out, and asserts his belief that no correct report of the action exists in print. Napier derives his account of it from Colonel Waller, whose statement is totally incorrect, and has been expressly contradicted by various officers (amongst others, by General King) who fought that day with Picton's division. Colonel Napier's strong partiality to the light division sometimes prevents his doing full justice to other portions of the army. In this instance, however, any error he has fallen into, arises from his being misinformed. He himself was far away to the left, fighting with his own corps, and could know nothing, from personal observation, of the proceedings of Picton's men. Opposed to a very superior force, including some of the best regiments of the whole French army, they had their hands full; and the Eighty-eighth, especially, covered themselves with glory. At one time, the Rangers had not only the French fire to endure, but also that of the Eighth Portuguese, whose ill-directed volleys crossed their line of march. An officer sent to warn the Senhores of the mischief they did, received, before he could fulfil his mission, a French and a Portuguese bullet, and the Eighth continued their reckless discharge. But no cross-fire could daunt the men of Connaught. "Push home to the muzzle!" was the word of their gallant lieutenant-colonel, Wallace; and push home they did, totally routing their opponents, and nearly destroying the French Thirty-sixth, a pet battalion of the Emperor's. Stimulus was not wanting; Wellington stood by, and, with his staff and several generals, watched the charge. The Eighty-eighth were greatly outnumbered, and Marshal Beresford, their colonel, "expressed some uneasiness when he saw his regiment about to plunge into this unequal contest. But when they were mixed with Regnier's division, and putting them to flight down the hill, Lord Wellington, tapping Beresford on the shoulder, said to him, 'Well Beresford, look at them now!'" And when the work was done, and the fight over, Wellington rode up to Colonel Wallace, and seizing him warmly by the hand, said, "Wallace, I never witnessed a more gallant charge than that made by your regiment!" Beresford spoke to several of the men by name, and shook the officers' hands; and even Picton forgot his prejudice against the regiment, whom he had once designated as the "Connaught foot-pads," and expressed himself satisfied with their conduct. Many of the men shed tears of joy. So susceptible are soldiers to praise and kindness, and so easy is it by a few well-timed words to repay their toils and perils, and renew their store of confidence and hope. And numerous were the occasions during the Peninsular contest when they needed all the encouragement that could be given them. After Busaco, when blockaded in the lines of Torres Vedras, their situation was far from agreeable. The wet season set in, and their huts, roofed with heather—a pleasant shelter when the sun shone, but very ineffectual to resist autumnal rains—became untenable. Every device was resorted to for the exclusion of the deluge, but in vain. Fortunately, the French were in a still worse plight. In miserable cantonments, short of provisions and attacked by disease, the horses died, and the men deserted; until, on the 14th November, Massena broke up his camp, and retired upon Santarem. The Anglo-Portuguese army made a corresponding movement into more comfortable quarters, and rumours were abroad of an approaching engagement; but it did not take place, and a period of comparative relaxation succeeded one of severe hardship and arduous duty. Men and officers made the most of the holiday. There was never any thing of the martinet about the Duke. He was not the man to harass with unnecessary and vexations drills, or rigidly to enforce unimportant rules. Those persons, whether military or otherwise, who consider a strictly regulation uniform as essential to the composition of a British soldier, as a stout heart and a strong arm, and who stickle for a closely buttoned jacket, a stiff stock, and the due allowance of pipe-clay, would have been somewhat scandalised, could they have beheld the equipment of Wellington's army in the Peninsula. Mr Grattan gives a comical account of the various fantastical fashions and conceits prevalent amongst the officers. "Provided," he says, "we brought our men into the field well-appointed, and with sixty rounds of good ammunition each, he (the Duke) never looked to see whether their trousers were black, blue, or grey; and as to ourselves, we might be rigged out in all the colours of the rainbow, if we fancied it." The officers, especially the young subs, availed themselves largely of this judicious laxity, and the result was a medley of costume, rather picturesque than military. Braided coats, long hair, plumed hats, and large mustaches, were amongst the least of the eccentricities displayed. In a curious spirit of contradiction, the infantry adopted brass spurs, anticipatory, perhaps, of their promotion to field-officers' rank; and, bearing in mind, that "there is nothing like leather," exhibited themselves in ponderous over-alls, à la Hongroise, topped and strapped, and loaded down the side with buttons and chains. One man, in his rage for singularity, took the tonsure, shaving the hair off the crown of his head; and another, having covered his frock-coat with gold tags and lace, was furiously assaulted by a party of Portuguese sharpshooters, who, seeing him, in the midst of the enemy's riflemen, whither his headlong courage had led him, mistook him for a French general, and insisted upon making him prisoner. And three years later, when Mr Grattan and a party of his comrades landed in England, in all the glories of velvet waistcoats, dangling Spanish buttons of gold and silver, and forage caps of fabulous magnificence, they could hardly fancy that they belonged to the same service as the red-coated, white-breeched, black-gaitered gentlemen of Portsmouth garrison.