полная версия

полная версияThe Arena. Volume 4, No. 23, October, 1891

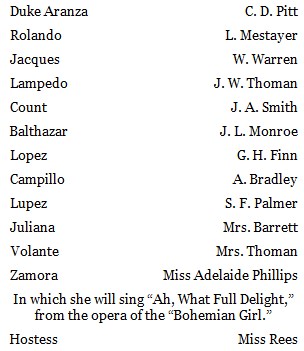

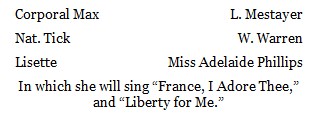

With the name of Adelaide Phillips there are many dear associations. When at seven or eight years of age I went to see her at the Boston Museum, the days she began to sing in “Cinderella” and the “Children of Cyprus.” How the old days rise up before me now. She was then in the spring of life, fresh, bright, and serene as a morning in May, perfect in form, her hands and her arms peculiarly graceful, and charming in her whole appearance. She seemed to speak and sing without effort or art. All was nature and harmony. Miss Phillips was a great favorite in Boston where she made her début at the Tremont Theatre in January, 1842, in the play of “Old and Young,” personating five characters, and introducing songs and dances. Although very youthful, she displayed great aptness and evinced remarkable musical talent. On the 25th of September, 1843, she first appeared on the boards of the Boston Museum, which then stood at the corner of Tremont and Bromfield Streets, where the Horticultural Hall now stands. The character which she assumed was Little Pickle in the “Spoiled Child.” At the opening of the present Museum, Nov. 2, 1846, Miss Phillips was attached to the company as actress-danseuse, and doing all the musical work necessary in the plays of that time. She was a most attractive member of the company, and as Morgiana (Forty Thieves), Lucy Bertram (Guy Mannering), Fairy of the Oak (Enchanted Beauty) was greatly admired. Her first decided success was as Cinderella. She was now about eighteen years of age, and the tones of her voice were rich and pure. She did not aim at “stage effect,” and her singing and acting were exquisite. At that time, 1850-51, Jenny Lind was in Boston. Miss Phillips was introduced and sang to her, and her singing was so brilliant, so ringing, so finished, that her hearer was astonished, and uttered exclamations of delight. The noble-hearted Jenny sent her a check for a thousand dollars, and a letter recommending Emanuel Garcia, who had been her own teacher, as the best instructor, and amid all the triumphs of her professional career, the affection and kindness which was showered upon her by Mlle. Lind, and her Boston friends, who came forward to show their willingness to aid Miss Phillips, was never effaced from her mind. After remaining abroad several years, she returned to Boston, appearing at the Boston Theatre Dec. 3, 1855, as Count Belino, in the opera of the “Devil’s Bridge,” supported by the popular favorite, Mrs. John Wood. She first appeared here in Italian opera a year later as Azucena in “Il Trovatore,” Madame La Grange being the Leonora. In this opera Miss Phillips was heard with great effect and never were her talents as an actress more conspicuously displayed. At the conclusion of the performance, the favorite singer received an ovation, applause rang through the theatre; the emotion which was evinced by her friends and admirers was evidently shared by herself. The character of Azucena remained a favorite one with Miss Phillips to the last. The characters in which she excelled were Maffio Orsini (Lucrezia Borgia), Rosina (Barber of Seville), and Leonora (Favorita). In 1879, she joined the Ideal Opera Company, and carried into it her vocal and dramatic culture. She continued with this company until December, 1881, when she made her last appearance on any stage in Cincinnati. Her last appearance in Boston was at the Museum, the home of her earlier triumphs, in the role of Fatinitza, a few months before her departure for the West in 1880. Ill health compelled her to relinquish all her engagements, and on the 12th of August, 1882, accompanied by her sister-in-law, Mrs. Adrian Phillips, who was the Arvilla in the early days of the Museum, sailed for Paris. After a few days’ rest in that city, they reached Carlsbad, and took apartments at Konig’s Villa, a pension for invalids. A few weeks thus passed until suddenly, on Oct. 3, 1882, the change came, and Adelaide Phillips was gone. The death of this gifted and good woman produced a painful sensation in Boston, and, indeed, all over the country she was deeply regretted. In private life she was amiable and kind-hearted, ever ready to assist the distressed. By her family and friends she was idolized, by the public she was respected for the purity of her life, and admired for her talents. Herewith I give a copy of the “bill” of Miss Phillips’ last benefit at the Museum, prior to her departure for Europe.

BOSTON MUSEUMFarewell Benefit of Miss Adelaide PhillipsRe-engagement of the eminent artists, Mr. CharlesPitt and Mrs. BarrettFriday Evening, June 27, 1851The Honeymoon

A great attraction in Boston, way back in the fifties, was Anna Cora Mowatt. Her engagements were always very successful, the theatre being crowded with fashionable and intelligent audiences. Mrs. Mowatt was not a great actress. Delicacy was her most marked characteristic. “A subdued earnestness of manner, a soft musical voice, a winning witchery of enunciation, and indeed an almost perfect combination of beauty, grace, and refinement fitted her for a class of characters in which other actresses were incapable of excelling.” Mrs. Mowatt was born at Bordeaux, France, during the temporary residence there of her parents about 1820. She married very young, and for a short time enjoyed every luxury that wealth could purchase. Her husband’s bankruptcy drove her to the stage, where she made her first appearance at the Park Theatre as Pauline, in “Lady of Lyons,” June 13, 1845. Her engagements here in Boston were played at the Howard Athenæum, then under the management of Mr. Wyzeman Marshall, who still lives, and can be seen upon the principal streets of Boston almost daily. The “houses” were very large, tickets being sold at public auction. At the termination of her engagement she was serenaded at the hotel, and throughout the country she met with the same flattering reception. Mrs. Mowatt’s favorite roles were Viola, Rosalind, and Parthenia, characters now fresh in the public mind, made so by Miss Julia Marlowe. Mrs. Mowatt made her last appearance on the stage at Niblo’s Theatre, N. Y., on the 3d of June, 1854. On the 7th of that month she became the wife of W. F. Ritchie. Mrs. Ritchie died in Paris a few years since, where she was much regretted by the social circle of which she was the admired star.

In 1852, at the National Theatre, which was situated on Portland Street, Charlotte Cushman commenced her farewell to the stage in the tragedy of “Romeo and Juliet.” Charlotte Cushman was now at the summit of her art. She was universally allowed to be the greatest tragedienne of the day. And this recognition was due to her fine genius. She owed nothing to artifice or meretricious attraction. Nothing was left to chance, for the indomitable spirit and zealousness with which she had sustained herself under adverse circumstances had done not a little to elevate her in the regard of her countrymen and admirers. This was the first of a series of “farewell engagements,” inaugurated by Miss Cushman, and continued to her real and positive farewell in 1875.

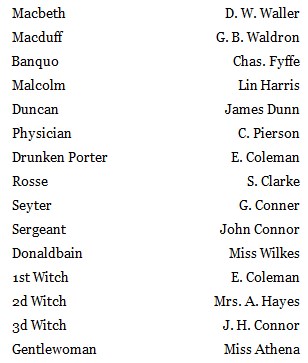

I have always had an objection to ladies personating Romeo, but I waived that feeling in favor of Miss Cushman. Her personation of Romeo was beautiful and even pathetic. The passionate grief of young Montague in the third act was subdued by a tearful pathos. Nothing could surpass her reading of the character: it was a triumph, and in a word it would be difficult to conceive anything more grand than this impersonation. It is difficult to conceive a character more highly dramatic or more impassioned than that of Lady Macbeth. The conflicts, emotions, and power of the ambitious queen were portrayed with a truth, a grandeur of effect, unequalled since by any actress. Miss Cushman’s impersonation of Meg Merriles was one of the finest illustrations of originality the stage ever witnessed. There was no effort to resemble the character. She entered the stage the character itself, transposed into the situation, excited by hope and fear, breathing the life and the spirit of the being she represented. In my opinion, when Charlotte Cushman died, so did Meg Merriles, and it will be many a day before the old gipsy queen will produce that indescribable effect upon an audience, as in the days of Cushman. At the Boston Theatre, June 2, 1858, Miss Cushman as Romeo, her farewell to the stage. At the same theatre, in 1860, another farewell, Miss Cushman as Romeo, who with the aid of Mrs. Barrow as Juliet, John Gilbert as Friar Laurence, and Mrs. John Gilbert as the nurse, made up a very strong cast. Here, at the Howard Athenæum in 1861, then under the management of that talented actor (who, by the way, was the best Hamlet I ever saw,) Edgar L. Davenport, Miss Cushman was announced April 11, 1861, positively her last night in Boston, when Romeo and Juliet was given with a remarkable cast. E. L. Davenport was the Mercutio, John Gilbert the Friar, John McCullough, Tybalt, Frank Hardenbergh, Prince Esculus, Dan Setchell, Peter, W. J. Le Moyne, Capulet, Miss Josephine Orton (a very brilliant actress, and now the wife of Benj. E. Woolf, of the Saturday Evening Gazette), Juliet, Mrs. John Gilbert as the nurse (she had no superior in this role), and Charlotte Cushman as Romeo, truly a fine array of talent, all of whom have passed away with the exception of Miss Orton and Mr. Le Moyne. This was Miss Cushman’s last performance of Romeo in Boston. In the spring of 1875, Miss Cushman played another farewell engagement, which proved in truth a reality. It was at the Globe Theatre, and Saturday, May 15, 1875, was announced as Miss Cushman’s farewell to the stage. Macbeth was the play, with Miss Cushman as Lady Macbeth. As an event worth remembering, I give the complete cast:—

A most inefficient company, exceedingly weak in the masculine department, while the actresses were barely tolerable. The highest anticipations of a brilliant engagement had been indulged in by the management, and bitter was their disappointment, and great the chagrin of Miss Cushman to find that this “positively farewell engagement” failed to create anything of a furore. The public had been so often deceived by these announcements, that they failed to respond to the box office. In this special performance of “Macbeth,” Miss Cushman was hailed with prolonged acclamations. Old admirers were there who still recollected her when she was the greatest ornament of the stage. Younger ones assembled to catch the last rays of a genius which had filled Europe and America with its splendor. The former sought this memory of days gone by, the latter came to pay deference to the verdict of a previous generation. At the close of the performance Miss Cushman was called to the footlights, there to receive the tribute due to her name and fame from the not over large audience. The spectacle was interesting, yet it was melancholy, not to say painful, to all who could feel with true artistic sympathy. Her last appearance was soon forgotten in the turmoil of dramatic events, but her name still gleams with traditional lustre in the annals of dramatic fame. Miss Cushman never again appeared in Boston, for on the 18th day of February, 1876, she breathed her last at the Parker House, Boston. Her funeral took place at King’s Chapel, in presence of a large concourse of people, and her body rests in Mount Auburn. Miss Cushman was a very wealthy woman, but her generosities were not numerous; even the little Cushman school, named in her honor, was forgotten in her will. Her relatives (nephews and nieces) reside, I believe, in Newport, R. I., and are the sole possessors of her large estate. I omitted to mention that Charlotte Cushman’s last appearance in public was as a reader in Easton, Penn., June 2, 1875.

THE MICROSCOPE FROM A MEDICAL, MEDICO-LEGAL, AND LEGAL POINT OF VIEW

BY FREDERICK GAERTNER, A. M., M. DWhen the microscope was first invented, it was regarded as a mere accessory, a plaything, an unnecessary addition, and an imposition upon the medical profession and upon the public in general. But since 1840, when the European oculists and scientists began to make microscopical researches and investigations, not only in the medical profession, but also in botanical and geological studies, etc., and since 1870, when, throughout the civilized world, the microscope came into general use in chemical analysis and other studies, it ceased to be considered an accessory, and is now regarded as an extremely necessary apparatus, especially in minute examinations and investigations; also in the advancement of every branch of science and art.

Had Galen, Celsus, Hippocrates, and the other great scientists of old, known the use of the microscope, they would have made no such grave blunders as in the advocation of the theory that the arteries of the human body contain and carry air during life, instead of oxygenized blood only. They were of the erroneous opinion that the blood stayed in the extremities, not to nourish and sustain the tissues, but simply to act as a humor in lubricating the same (tissues).

Then, again, had it not been for the microscope, the great English surgeon and physician, James Paget, would not have discovered that deadly parasite, the trichina-spiralis, which had already slaughtered thousands upon thousands of human beings. And yet the existence of trichina-spiralis may be dated as far back as the time of Moses, who even then advocated prohibition of the use of pork as a food, and who considered pork not only an unwholesome food, but dangerous and even poisonous.

The microscope is certainly the best friend that a scientist can have. A physician without a microscope is like a man without eyes: he is uncertain and unprotected and must be considered incompetent, simply because he cannot arrive at a correct and positive conclusion in diagnosing and prognosing his case.

The value of the microscope cannot be overestimated, at least in the examination of the sputa of a human being, and thus being able to state positively whether or not the man is suffering from consumption (Tuberculosis). How important it is to be able to state with certainty at an early date whether or not the patient is suffering from cancer of the stomach, by examining the vomits microscopically.

The microscope is composed of a simply constructed horse-shoe or tripod base with a column, tube, reflector, and lenses of different magnifying powers, ranging from one to five thousand diameters. It is a most extraordinary and at the same time a most simple apparatus, an invaluable instrument, whose use any person with a little skill can learn in a few hours’ practice.

Much has already been published of late years concerning the microscope applied in a medico-legal sense (examinations). This surely is a very broad field and much remains for future observation and investigation. Everything that concerns medical examinations in a legal sense or legal examinations in a medical sense can be facilitated and accurately determined by the use of the microscope. For instance, let me call your attention to the world-renowned “Cronin” case of Chicago, in which the medical experts demonstrated to a certainty that the blood, hair, and brain matter found in the Coulson cottage and sewer drop were those of a human being. And what was still more remarkable they demonstrated by the microscope accurately and positively that the hair and blood found in the cottage and fatal trunk were those of the late Dr. Cronin, only in a modified condition.

Without a doubt the microscope is the most advantageous and most efficacious apparatus that a scientist has ever invented and constructed. It is an especially powerful factor in enlightening complex and difficult cases concerning medico-legal examinations, where the combined efforts of an attorney and an expert microscopist are required. Within the last decade, scientists have demonstrated to a certainty the possibility of distinguishing old and dried human blood spots, whether on clothing, wood, iron, or any other object, from those of animal blood. Scientists, especially pathologists and histologists, have demonstrated the great value of the microscope in distinguishing not only the skin, blood, hair, and brain matter, but also the excretions and secretions of the human body from those of animals.

Again, the microscope applied in medico-legal practice, particularly in malpractice suits, suits for damages, those requiring the detection of adulteration of food or drink, is of the greatest importance. It is not less valuable in determining the purity of an article, especially whether or not the food or drink has spoiled or undergone fermentation, and in detecting the accumulation and development of microorganisms such as germs, bacilli, etc. Prominent among these uses are of course the detection of oleomargarine, the adulteration of drugs, liquors, milk, groceries, sausages, etc.

The utilization of the microscope as a factor in the solution of legal difficulties is as interesting as it is valuable, and in that connection I wish to cite a few lines from an exhaustive paper read by the Hon. Geo. E. Fell, M. D., F. R. M. S., before the American Society of Microscopists, relating to the “Examination of Legal Documents with the Microscope.”

“This subject is of practical importance, in which the value of the microscope has again and again been demonstrated. On several occasions have we been enabled to clear the path for justice to ferret out the work of the contract falsifier, and shield the innocent from the unjust accusations of interested rogues. The range of observations in investigations of written documents with the microscope is a broad one. We may begin with the characteristics of the paper upon which the writing is made, which may enable us to ascertain many facts of importance; for instance, a great similarity might indicate, with associated facts, that the documents were prepared at about the same time. A marked dissimilarity might also have an important bearing upon the case. The difference of the paper may exist in the character of the fibres composing it, the finish of the paper whether rough or smooth, the thickness, modifying the transmissibility of light, the color, all of which may be ascertained with the microscope.

“The ink used in the writing may then be examined. If additions have been made to the document within a reasonable time of its making, microscopic examination will in all probability demonstrate the difference by keeping the following facts in view: Some inks in drying assume a dull, or shining surface; if in sufficient quantity, the surface may become cracked, presenting, when magnified, an appearance quite similar, but of a different color, to that of the dried bottom of a clayey pond after the sun has baked it for a few days. The manner in which the ink is distributed upon the paper, whether it forms an even border, or spreads out to some extent, is a factor which may be also noted. The color of the ink by transmitted or reflected illumination is also a very important factor. This in one case which I had in hand proved of great importance and demonstrated the addition of certain words which completely annulled the value of the document in a case involving several thousand dollars. And in a certain case where the lines of a certain document were written over with the idea of entirely covering the first written words, the different colors of the inks could not be concealed from the magnified image as seen under reasonably low powers of the microscope.”

The value of the microscope in this field of research is so great and the facts elicited by it so vital, I wish to emphasize its practical utility as strongly as possible. Of course the principal object in such an examination of written or printed documents is the erasures or additions; then the coloring of different inks applied and the mode of their execution. As to erasures, this can be accomplished in two ways, either by the use of a penknife or by a chemical preparation. The former is the one most commonly resorted to, and is effected in the following manner. With a well sharpened knife blade the surface of the paper is carefully scraped until all objectionable lettering and wording appear to the naked eye to have been effaced; but under a microscopical examination the impression made by the strokes of the pen may easily be detected, while the different colors of the inks are still plainly visible under the microscope.

The second method is by the application of a chemical preparation by which the ink is made soluble and is then easily removed from the paper by means of a blotter or absorbent cotton. Of course this method is also an imperfect one and the letters can easily be traced by close observation. When a chemical preparation has been used for erasing purposes, I find that in most cases it leaves a stain and also that the fibres of the paper are more or less destroyed by the chemical used; thus always leaving evidence that the document has been tampered with.

George E. Fell in his excellent paper says: “The eye of the individual making the erasures is certainly not sufficient, and even with the aid of a hand magnifier, the object might not be effectually accomplished. We will find that the detection of an erasure made by the knife is a very simple matter and may be detected by the novice. An investigation may be made by simply holding the document before a strong light and this is usually all that is necessary to demonstrate the existence of an erasure of any consequence.

“This is, however, a very different matter from making out the outlines of a word or detecting the general arrangement of the fibres of the paper, so as to be able to state whether writing has been executed on certain parts of the document; and again, when we enter into the minutiæ of the subject, we will find that the compound microscope will give us results not to be obtained by the simple hand magnifier.”

On several occasions I have had the opportunity for demonstrating with the microscope additions made to certain documents, two of which were wills (testaments); these additions were made in the following manner:—First an erasure was made and then the additional matter written over the erasure. With the microscope I could at once detect the erasure beneath the addition; also the different colors of the inks. Then, and this is the most important result of the microscopical examination, by close observation, I could discern the strokes of the pen in the original lettering as well as those of the additional lettering, and finally the general mode of their execution.

In regard to the examination of legal documents, United States currency, printed and written matter, mutilated documents, including forgeries, etc., from a legal point of view (as to their genuineness), it will suffice to say that the principal features are, as already stated, first, the detection of erasures and additions; second, the comparison of the colors of the different inks used in the original and in the additional lettering, and finally the mode of their execution. This includes of course a careful observation of the original writing as to the general and comparative expression. In the observation of the characteristics of the letters constituting the document, I will call attention especially to the shading and general formation of the letters, that is, the stroke of the pen either in a downward or upward movement. This comparison includes both capital and small letters and even punctuation.

All these things, as well as the grammatical and orthographical relationship and comparative differentiations, must be taken into consideration in order to enable the microscopical examiner to give a positive opinion.

A microscopical examination of paper documents, such as wills, notes, checks, etc., as to whether or not they have been mutilated or forged, is certainly the most reliable test, and by far the easiest and simplest method of determining the authenticity or spuriousness of a document. An expert microscopist and observer can at once arrive at a correct and positive conclusion as to the genuineness of an autograph.