полная версия

полная версияThe Arena. Volume 4, No. 23, October, 1891

Before writing on this subject, he must have become acquainted with the late writings of Prof. Richard T. Ely, and The New Nation of Edward Bellamy, whose standing motto is: “The industrial system of a nation, as well as its political system, ought to be a government of the people, by the people, for the people.” And further it says (Aug. 1, p. 426): “This step necessarily implies that under the proposed national industrial system, the nation should be no respecter of persons in its industrial relations with its members, but that the law should be, as already it is in its political, judicial, and military organization,—from all equally; to all equally.” Equality, Fraternity, Liberty, are the words.

Pages with similar import can be cited from every exponent of Nationalism. It all means that our “government” will not be of force or of authoritarianism, but simply public conveniences and needs regularly secured, without being farmed out by franchise laws to monopolistic corporations for their benefit.

Notice further, that the extension of this government—action of the people is not to do nor to extend to everything nor to anything, but to the material needs and industries of the people, beginning with those natural monopolies like railroads and telegraphs, ending with trusts, etc., which have passed beyond competition. This simple limit makes the cry of “universal despotism” absurd. The tyranny and robbery of the few is simply abolished by the people, in equitably resuming the franchise granted by them, and doing the work for all cheaper and better. There is no tyranny to the few in this; and as to the many or all,—the tyranny of having things you want done for you is laughable. Our anarchists invariably submit to the tyranny of our free nationalized Brooklyn Bridge instead of swimming the river, or using the ferry company, as they are at full liberty to do. We had a hard fight to get this bridge, for it displaced monopolies. When the other monopolies, we have referred to, are displaced by the people, there will be the same wonder that their tyrannies and exactions were ever submitted to. We have found, and will find, that that government is the best which serves and administers the most, for it will cost and restrain the least. The government that serves and protects the people will not need to compel them. Now its main business is to hold them down while they are being robbed.

But, says Mr. Savage, these advantages would be attended by a frightful “paradise of officialism”—a helpless subordination—in which “the individual if not an officer would only count one!” We cannot appreciate the horror of having more of “a paradise” about officialism than we have in our present corrupt, inconstant, and servile system of political Bossism, even if the individual could only “count one.” But Mr. Savage does know, or ought to know, that the very first step of Nationalism is to nationalize our “politics,” so as to restore the initiative of political action to the people, and render the abuses to which he refers impossible. He seems to suppose that Nationalism is to be executed by Tammany Hall! Indeed, his capital as an opponent of Nationalism consists in loading it up with European paternalism and American political corruption, both of which it was invented to render impossible. Suppose the “politics” of New York were nationalized so that the City should no longer be a mere annex of Tammany Hall, but so that every citizen might “count one,” under legal provisions for the vote and expression of the people without regard to party or boss—who would be wronged? Politics must be annexed to our government by such legal provisions, instead of being left to boss monopoly or mobocracy. There is no freedom possible without a common law and order to ensure and protect it. The trouble is now that all of our politics are outside of any law or order. “Count one!” Even that is now impossible. We don’t count at all, no more than if we lived in Russia. But how many does Mr. Savage want an individual to count? His idea of political freedom seems to be that of our old “free” Fire Department, which was a monopoly entirely “voluntary.” It gave us a fire and free fight nearly every night, developed its “Big Six” Tweed into a “statesman,” and consolidated Tammany Hall into the model political “combine” of the world—as a monopoly. The custom is to dispose of the offices of the people as profitably as it can with safety, and to divide the proceeds for the benefit of the combine. One of our purest and best judges publishes his last contribution as $10,000, besides his other election expenses. This is the model to which the State and Nation must conform, for such is the condition of success. Under that plan Governor Hill manages the State of New York, and President Harrison, through “Boss” Platt, has just removed Collector Erhardt from the New York custom house, under the imperative necessity of the same method.

As long as our Government is run by partisan politics, outside of law, there is no other alternative but this way or defeat. The pretence, under this method, of civil service reform or fair tenure is sheer hypocrisy. The Tammany method is the only condition of success, and every practical politician knows it and adopts it. Nationalism proposes the only remedy. It would remove every department from political control, and restore the political initiative to the people by requiring their common action under general laws for that purpose, and suppressing as criminal the Boss conspiracy system, which causes the counting of less than one by anyone. Do you say it cannot be done? Well! look at that Fire Department. The indignation of “the State” finally replaced it by a paid civil service, “nationalized” department. Since then our fire affairs have run cheaply, effectively, smoothly, though in a most trying environment. Fires seldom occur, and seldom extend beyond the building in which they occur. The old abuses, political and other, have stopped. The men, appointed and promoted for merit, are highly respected and secured against causeless removal, accident, sickness, and old age. “Helpless subordination” ended by an appeal to the law which gave prompt redress. The heads of the departments and the officers count one and the attempt to count more would be an assumption not submitted to for a moment, for no one needs to submit. Extend this method mutatis mutandis over our Cities, States, and Nation, and also over legalized political election departments for the whole people,—and the nail will be hit on the head! The last nail in the coffin of party monopoly and corruption.

To excuse himself from not aiding this reform Mr. Savage cries, visionary, unpracticable! Thus he says:—

“3. Nobody is ready to talk definitely about any other kind of Nationalism [“Military Socialism” meaning], for nobody has outlined any working method. If it is only what everybody freely wishes done,—and this seems to be the Rev. Francis Bellamy’s idea—then, it is hard to distinguish it from individualism. At any rate it is not yet clear enough to be clearly discussed.”

All this shows Mr. Savage to be strangely misinformed. The Rev. Francis Bellamy is right. Every impartial person does want the kind of Nationalism Nationalists are after, as soon as their minds are disabused of this foolish talk about military despotism, and helpless subordination, etc., for every one can see that it works for the liberty, equality, and welfare of all.

Misinformed, is the word for Mr. Savage. For if he had kept but one eye on this world, as Humboldt said every well regulated chameleon and priest is in the habit of doing, he would have known that every word of this “No. 3,” above quoted, is exactly wrong: To wit: The other kind of Nationalism, which is not military despotism, has not only been definitely talked about but definitely put in practice, not only in the New York Fire Department, but in our schools, roads, canals, waterworks, post-office, and in many other ways the world over! And never (“hardly ever”) has monopoly been able to recover its chance to tyrannize and rob!

“No definite talk”! Yet our present Postmaster-General is asking Congress for the postal telegraph; and the Interstate Commerce Law is to be made practical to head off the People’s Party? Let Mr. Savage pick up the very same August ARENA which contains his article, and read the clear and definite articles of C. Wood Davis, “Should the Nation own the Railways?” and of R. B. Hassell, on “Money at Cost,” and then tell the Editor with a straight face that they are not “clear enough to be clearly discussed!” The facts, laws, and arguments are definitely there, and clearly discussed. Why have we not the discerning eyes and impartial brains of Mr. Savage to read them?

We ask Mr. Savage to bring such eyes and brains to bear, and we defy him to show any other plan by which the fatal monopolies, which are natural or beyond competition, can be usefully and safely checked, controlled, or destroyed. The attempts to do this by legal prosecutions have notoriously failed. How to replace monopolies and yet increase the benefits they have conferred is the question of our age, and Nationalism answers it. Mr. Savage, as we have shown, admits the difficulty. We are entitled then to a practical answer, or to silence. Ridicule, however witty, is neither answer nor remedy.

But instead of silence we have his amusing “fourth and lastly,” thus:—

“4. Nationalism, as commonly understood, could mean nothing else but the tyranny of the commonplace.”

The way in which Nationalism is commonly understood or misunderstood, is not the question; but how is it correctly understood,—that is the concern of every fair mind. When thus understood it seems to be just what Mr. Savage wants. For he agrees with Mr. Bellamy that if “it is only what everybody freely wishes done,” then it would be his “individualism” and all right. Thus he approves of democracy; for, he says, “it only looks after certain public affairs, while the main part of the life of the individual is free.” This is Nationalism to a dot! Yet he strangely concludes: “That Nationalism, freely chosen, would be the murder of Liberty, and social suicide.” But if “freely chosen” will it not be the same as his individualism? and what everybody wants,—and so all right? Such would be his democracy certainly, but then how can this Nationalism also “freely chosen” commit murder and suicide, and both at once? Strange! That certainly would not be the tyranny of the commonplace.

Neither would Nationalism in any correct sense be such tyranny; and for these reasons:—

1. Government would for the first time in the history of the world, evolve beyond paternalism. It would be industrial cooperative administration, for the equal benefit of all, protection of the liberty of all, and such defence and restraint only as these main objects require. Government would thus be the material foundation upon which liberty, originality, and the original—the uncommonplace—could stand and be protected. The key to liberty is the “separation of the temporal and spiritual powers;” but Nationalism does even more than that. It limits Government to the provision of the common needs of all, and then protects all, in the enjoyment of their “uncommon-place.” Read for instance the remarkable article of Oscar Wilde on “The Soul of Man under Socialism.” He expresses the feeling of the artists and poets of the world. They want Nationalism so that originality and free healthy development may at last have a chance,—and an audience. What the people need in order to become an audience is the same thing that originality needs, emancipation from drudgery and from the dependence of parasitism.

2. This emancipation can come only from the great saving of time and of waste by Nationalism; and the division of labor by which it will enable each to follow the occupation to which he is inclined, and to which he will be the best prepared by nature and education. Man is an active animal, and the condition of life is that of some work. Now the work is imposed by the tyranny of man and circumstances; then it will be rather a matter of choice. In the order instead of the anarchy of industry there will be some relief. To use the grand prophecy of Fourier:—

“When the series distributes the harmonies,The attractions will determine the destinies.”Given a material foundation for man and his education, so that he may have the mental and material means of acting his part, and continuing his development, then the individual will have inherited an environment in which life will be worth living, and which only the favored inherit now. Civilization will certainly have ever new demands in order to equate its ever changing conditions; and ambition, heroism, and originality will simply rise to newer and higher fields. The idea that the temporal state will not continue to encourage and protect liberty, genius, and originality is most absurd. That has been its general course against the sects and monopolists of religion and opinion which have ever been the persecutors. Mr. Savage throws down a queer jumble of names, viz.: “Homer, Virgil, Isaiah, Jesus, Dante, Shakespeare, Angelo, Copernicus, Galileo, Goethe, Luther, Servetus, Newton, Darwin, Spencer, and Galvani,”—and says, “consider them,” where would they have been before the “governing board” of Nationalism? We consider and answer: every one of them would have been free, and protected and encouraged in the exercise of his highest gifts.

Even under such defective government as then existed, each had its aid and support, and each was persecuted by the monopolistic sects and factions sure to get authority in the absence of some general temporal control, which is absolutely necessary for the purpose of protecting freedom of thought, of expression, and of action. From Homer’s chieftain, Virgil’s emperor, Goethe’s duke, on to the end of the list, we owe all they have done for us to the temporal governments of their time, with a possible exception of Spencer, more apparent than real. Even the Roman Pilate (if we are to take the reports?) let Jesus have a freedom to tramp and preach in Palestine that would not be allowed in Boston for a day, and then stood by him, and when compelled, by the unnationalized nature of his office, to give up to the Anthony Comstocks and the priestly Monopolists and Pharisees of that day, he nobly said, “I find no fault in him,” and publicly washed his hands of the whole bloody affair. So was it with Servetus. Temporal, much less a nationalized, Switzerland would have rescued him from the clutches of the Calvinistic monopoly of Geneva. “Toleration?” repeats Mr. Savage tauntingly. We reply, yes! We want a general temporal government which will protect liberty, and ensure that every priest, sect, fanatic, and phase of thought and opinion shall tolerate every other. This Nationalism only can do.

We insist, and have for years, that the government monopolies of opinions, morals, and force, farmed out to amateur societies of Comstocks and Pinkertons, should be withdrawn. If necessary to public safety, let power be exercised only by the government directly responsible to the people. It is this attempt to govern by monopolies in the interest of sects or industrial classes that gave rise to every one of the abuses to which the editor of The Arena has well called attention as “outrages of government.” They are only outrages of government by monopolies for monopolies, and which it is the fundamental condition and mission of Nationalism to end forever. In all these cases, and in every case, the advocates and apologists of Anarchy, or of Laissez-faire must not mistake their position, they are inevitably the allies of the oppressor. The integration of special classes, sects, and interests, is the natural law making “toleration” more and more impossible. The integral integration, then, of all for the equal support, and for the equal protection of all, in mutual harmony and progress, is the only condition of our liberty, peace, and safety. No rule in Arithmetic is plainer than this law of Sociology, and Nationalism is its expression.

“RECOLLECTIONS OF OLD PLAY-BILLS.” 5

BY CHARLES H. PATTEEIn offering to the public my recollections of old play-bills I cannot be said to be travelling over familiar ground. For it is worthy of remark that while many bygone periods of theatrical history have found their chroniclers, their panegyrists, their enthusiastic remembrances, the space filled by the events of the Boston stage of 1852 to the present day has remained without a comprehensive survey, without a careful retrospect of its many notable and brilliant illustrations. To supply this void, to endeavor at once to preserve the memories of past grandeurs (already fading with the generation who enjoyed them), and to furnish to the younger portion of theatre-goers some conception of what the stage has been in its “palmy days,” I have employed my leisure in putting together this history of old play-bills. The changes which have overspread modern society, vast and manifold as they are admitted to be, are, perhaps, nowhere more perceptible than in the region known as the theatrical world. To one who has formed a link in that chain which formerly connected the higher ranks of society with the taste for dramatic art—with the cultivation of the beautiful and imaginative in both opera and drama—to such a one the contemplation of the altered relations now between the patrons of the drama and the ministers of art suggest many comparisons. The first stage performance I ever witnessed will not easily be forgotten. It took place in the Boston Museum in 1850; the plays were “Speed the Plough,” and a local drama (now happily banished from the stage) called “Rosina Meadows.” Thomas Comer, who was leader of the Museum orchestra, a gentleman, actor, and musician, took me under his charge and seated me in the orchestra near the bass-drum and cymbals, where I remained until the end of the performance. The time flew in unalloyed delight until the fatal green curtain shut out all hope of future enjoyment. William Warren, W. H. Sedley Smith, Louis Mestayer, J. A. Smith, Adelaide Phillips, Louisa Gann, who became the wife of Wulf Fries, the celebrated ‘cello player, residing in Boston, Mrs. Judah and Mr. and Mrs. Thoman, all of whom are dead with the exception of J. A. Smith, who is now an inmate of the Forrest Home in Holmesburg, Penn., and Mrs. Thoman, who was a charming actress, and for several seasons a great favorite with the Museum patrons. She was divorced from Thoman and became the wife of a Mr. Saunders, a lawyer residing in San Francisco, who died some years since. Mrs. Saunders is now living in the above city in retirement, and through the kindness of her cousin, Joseph Jefferson, is enjoying the ease of a genteel competence.

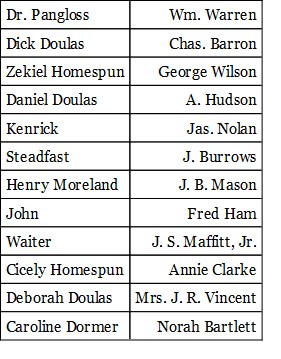

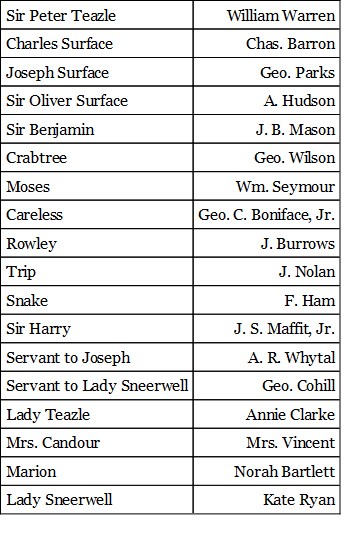

William Warren and Adelaide Phillips were the first performers who ever made a lasting impression upon me. William Warren, great as an artist and as a man. With pleasure do I pause from the record of events to present a description of the illustrious actor. He has now passed away, and to future generations the faithful description of one who delighted their fathers, and who can never be replaced, will surely prove welcome. He made his first appearance in Boston at the Howard Athenæum, Oct. 5, 1846, as Sir Lucius O’Trigger in the “Rivals” (the same character that W. J. Florence is now personating with the Jefferson combination). Mr. Warren remained at the Athenæum but one season, and during that time commanded the admiration of his audiences. Mr. Charles W. Hunt, a very good actor, had held the position of comedian at the Boston Museum for several seasons, but owing to some misunderstanding, left the establishment. Mr. Warren was engaged to fill the vacancy, and on the night of the 23d of August, 1847, he made his first appearance on the stage of the Museum as Billy Lackaday in the old comedy of “Sweethearts and Wives,” and as Gregory Grizzle in the farce of “My Young Wife and Old Umbrella,” and from that time, with the exception of one year’s recession (1864-5) to the termination of the season of 1882-3, was a member of the Museum company. Thirty-six years is a long test applied to modern performers, and he that could pass such an ordeal of time, must possess merits of the very highest order, such as could supersede the call for novelty, and make void the fickleness of general applause. All this Warren effected. The public, so far from being wearied at the long-continued cry of Warren, elevated him, if possible, into greater favoritism yearly. But his place is not to be supplied. No other actor can half compensate his loss. Independent of his faculties as an actor, so great a lover was he of his art that he would undertake with delight a character far beneath his ability. Other actors will not condescend to do this or else fear to let themselves down by doing so. Warren had no timidities about assuming a lesser part, nor did he deem it condescension. Artists of questionable greatness may deem it a degradation to personate any save a leading part. Warren felt that he did not let himself down, he raised the character to his own elevation. From this it follows that no great actor within my recollection had undertaken such a variety of characters. He was found in every possible grade of representation. His acting forms a pleasant landing place in my memory. As I wander backward, no other actor has ever so completely exemplified my idea of what a genuine comedian ought to be. He gained the highest honors that could be bestowed upon him in Boston, and established his claim to be considered one of the most chaste and finished of American actors. From Sir Peter Teazle to John Peter Pillicoddy, from Jesse Rural to Slasher, from Haversack to Box and Cox, he was equally great and efficient. I have heard it remarked that the late W. Rufus Blake stood without a rival as Jesse Rural, while Henry Placide was the best of Sir Peter Teazles. Never having witnessed the performances of those gentlemen, I am unable to speak of their merits, as older writers have sounded their praises for a generation. Saturday, Oct. 28, 1882, was the fiftieth anniversary of Mr. Warren’s adoption of the stage. The entertainment consisted of an afternoon and evening performance. The “Heir at Law,” constituted the bill for the day performance, and “School for Scandal,” was given in the evening. It was impossible indeed for the arrangements to be more perfectly accomplished. The character of the audiences was even more gratifying than its numbers. Never had been such an assemblage in any theatre. A great number of elderly persons, both men and women, interspersed with the younger people, gave a beautiful shading to the amphitheatre picture, as it was seen from the boxes. It was a tribute of respect to one who had been so long the pride of Boston. As a matter of record I give the complete cast of the plays:—

Heir at Law

Mr. Warren remained at the Museum during the entire season, and made his last appearance on any stage as old Eccles in “Caste,” in May, 1883. From that time to the day of his death, which sad event occurred Sept. 21, 1888, Mr. Warren made Boston his home, residing at No. 2 Bulfinch Place, the residence of Amelia Fisher, where he had lived since the departure of his cousin, Mrs. Thoman, for California, in 1854. Mr. Warren left property to the value of a quarter of a million dollars. He made no public bequests, but bequeathed his entire estate to his relatives. Who is there in Boston that has not heard of Miss Amelia Fisher, the “dear old lady” of Bulfinch Place, where she has lived so many years, and at whose hospitable board so many have been welcomed? Miss Fisher, accompanied by her sisters Jane, afterwards Mrs. Vernon, who was for many years the “first old woman” of the New York stage, and Clara, afterwards Mrs. Gaspard Maeder, married in America in 1827, and made her début at the Park Theatre, N. Y., singing a duet, “When a Little Farm We Keep,” with William Chapman. Miss Fisher was for several seasons attached to the Tremont Theatre in Boston, and although possessing respectable abilities both as singer and actress, never attained the prominent place in the profession accorded to her more talented sisters. Miss Fisher retired from the stage in 1841, and for some years was a teacher of dancing in Boston. For over thirty-seven years Miss Fisher has entertained at her home a swarm of dramatic celebrities. Here Mr. and Mrs. James W. Wallack, Charles Couldock, Peter Richings and his daughter Caroline, Mrs. John Hoey, and Fanny Morant, dined together where, in later days, Joseph Jefferson, George Honey (the celebrated English comedian), Ada Rehan, Annie Pixley, Mr. and Mrs. McKee Rankin, and Mr. and Mrs. Byron, ate their supper in the old kitchen, and were merry with wit and song. Since the death of Mr. Warren, Miss Fisher has not enjoyed good health, although her hospitable board is still surrounded by her friends and guests.