Полная версия

The Gates of Africa: Death, Discovery and the Search for Timbuktu

Sailing from England to Egypt could hardly be called exploration in the eighteenth century â there was regular traffic across the Mediterranean, though the going was often far from easy. European interests in India and further east meant that frequent caravans crossed the desert between Cairo and Suez (the Suez Canal was still eighty years away). Although there was a risk of attack by Bedouin tribes, whom the Pasha in Cairo was powerless to control, Ledyard could be confident of passing that barrier. Assuming that he got this far, his problems would just be beginning. For one thing, Christians had long been banned from sailing on the Red Sea. The official explanation for this was the desire to protect the purity of the Muslim holy places at Mecca and Medina, although there was certainly an equally strong desire to keep European traders away from the lucrative Red Sea trade. James Bruce claimed to have persuaded the Egyptian Pasha, Muhammad Bey Abu Dahab, to allow British ships to sail to Suez. And as Bruce had been in touch with Banks since his return to Britain, it is likely that Ledyard also knew about this agreement. What he perhaps did not know was that since Bruceâs visit to Egypt, the Ottoman authorities had issued a Hatti Sharif, an instruction to the Pasha, judges, imams and indeed just about anyone else with any authority over the Egyptian Red Sea coast: âThe Sea of Suez is destined for the noble pilgrimage to Mecca,â it began unequivocally. âTo suffer Frank [European] ships to navigate therein, or to neglect opposing it, is betraying your Sovereign (the Ottoman Emperor), your religion, and every Mahometan.â9

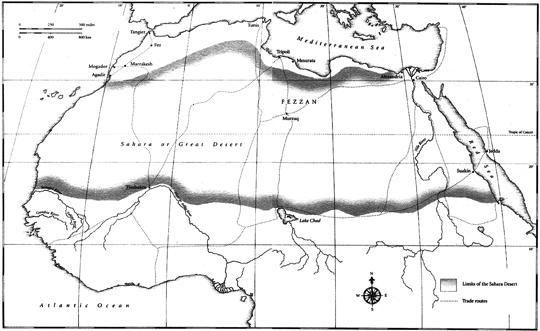

It was going to be an achievement just to reach the Nubian shore. A quick look at the map of Africa will help to point up some of the hazards of the proposed journey: Ledyardâs route lay through the Nubian Desert, over the Nile and then thousands of miles across the entire breadth of the Sahara, through countries whose political situation was completely unknown to the Association and, indeed, to just about anyone else outside Africa. To guide himself through all this, Ledyard had a map drawn using speculation, hearsay and wishful thinking. What sort of man would agree to a mission of this sort, which others might have regarded as an elaborate form of suicide?

Ledyard in Cairo on his way to Suakin, Lucas in Tripoli: a grand plan to bisect the northern half of Africa in 1788

Connecticut-born John Ledyard was already famous as independent Americaâs first explorer, but then travel was in his blood: his father was a sea captain who traded between Boston and the West Indies. After his fatherâs early death in 1762, Ledyardâs upbringing was as unsettled as the times, and there was something inevitable about his signing up with one of his fatherâs friends and sailing out of New England.* In 1775, now twenty-four years old, he crossed to England in the hope of making his way in the world, which he did, though not as he had expected.

In England Ledyard heard of Captain Cookâs preparations for his third voyage to the Pacific. Cook, already a legend as a navigator and explorer, was going in search of a northern passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and Ledyard decided to join him. Marine Corporal Ledyard sailed out of Plymouth on Cookâs ship the Resolution in July 1776, and sailed back in the autumn of 1780. He had been on the beach on Hawaii when Cook was murdered, opened negotiations with Russian fur traders in the north-west Pacific, been promoted to sergeant and made a name for himself as a solid and reliable member of the expedition. He had also discovered his path in life. He was, he explained, not a philosopher but âa traveller and a friend to mankindâ.10

âMy ambition,â Ledyard wrote to his mother in his usual convoluted style after the Resolution voyage, âis to do every thing, which my disposition as a man, and my relative character as a citizen, and, more tenderly, as the leading descendant of a broken and distressed family, should prompt me to do ⦠My prospects at present are a voyage to the East Indies, and eventually round the world. It will be of two or three yearsâ duration. If I am successful, I shall not have occasion to absent myself any more from my friends; but, above all, I hope to have it in my power to minister to the wants of a beloved parent ⦠Tell [my sisters] I long to strew roses in their laps, and branches of palms beneath their feet.â He would be a sybarite, a poet, a man of means. First he wanted a share of the âastonishing profitâ to be had buying furs in the American north-west. But how was he to get there?

At that time, neither Europeans nor members of the newly united states of America had found an overland route across the American continent to the Pacific. Ledyard first looked for an American backer to help him sail south around the Americas to the west coast. When that plan was unsuccessful he moved to Europe, looking for backers first in Spain and then in France. By the time he reached Paris, it was becoming clear, even to a man of his irrepressible optimism, that no one was going to provide him with a ship to go and trade in furs.

Before leaving the States Ledyard had written a book, A Journal of Captain Cookâs Last Voyage. Its publication had established him as a celebrity, even in Europe, where he was fêted as the first American explorer. Marooned in Paris, he at least had the consolation of becoming part of the cityâs American community and enjoying the patronage of the American Consul, Thomas Jefferson. The Consul clearly liked the young man, whom he described as having âgenius, an education better than the common, and a talent for useful & interesting observationâ.11 Perhaps it was Jeffersonâs patriotic influence that began to rub off on Ledyard during this period. Still determined to reach the American north-west, he wrote to his family with more enthusiasm than clarity that âthe American Revolution invites to a thourough [sic] discovery of the Continent. But a Native only could feel the pleasure of the Atchievement [sic]. It was necessary that an European should discover the Existance [sic] of that Continent, but in the name of Amor Patria. Let a Native of it Explore its Boundary. It is my wish to be the Man.â

Ledyard now changed his plans, and in the autumn of 1786, with a little money provided by Banks, to whom he had been recommended, he left Paris. His plan was to travel overland through Europe to Russia, although the Russian Empress Catherine the Great had already refused him permission to travel through her lands, assuming he was a threat to the Russian monopoly on the fur trade. In this she was right, because from Russia he intended to sail to the American north-west and make contact with the fur traders he had met when travelling with Captain Cook. At this point Ledyard confessed to an even greater ambition: Siberia was not the goal but a step on the way. He wanted to be the first person to circumnavigate the world by land.

If desire alone were enough he would have succeeded, but weather and politics conspired against him. During the winter of 1786 he crossed from Stockholm to St Petersburg and in June 1787 left for Siberia. Three months and six thousand miles later, having travelled much of the way on foot, he reached the Okhotsk Sea, but was unable to cross to Kamchatka, where he intended to join the fur traders, because the sea had frozen. He travelled back to Yakutsk to sit out the winter as best he could on meagre resources. He probably would have survived until the thaw. But in March 1788 his luck ran out: the Empressâs agents caught up with him and he was arrested, accused of being a French spy, marched back across Russia to the Polish frontier and warned that he would be executed if he dared to enter Russian territory again without Imperial permission. He used the last of his money to reach Königsberg (present-day Kaliningrad), where he found someone prepared to lend him £5 on Sir Joseph Banksâ credit. From there, he headed for Soho Square.

The day he reached Yakutsk â it was 18 September 1787 â Ledyard had felt the profits from fur dealing, and the possibilities they would create, to be within his reach. In pensive mood, thinking of the journeys ahead, he confided to his journal, âI have but two long frozen Stages more [from Yakutsk to the coast and then across the Pacific] and I shall be beyond the want or aid of money, until emerging from her deep deserts I gain the American Atlantic States and then thy glow[i]ng Climates, Africa explored, I lay me down and claim a little portion of the Globe Iâve viewed.â12 The American journey was not to be, but there was something prophetic about the mention of Africa.

When Ledyard appeared in Soho Square, Banks scribbled a note of introduction in his spidery hand and sent him around to Henry Beaufoyâs house in Great George Street. Beaufoy was impressed. âBefore I had learned from the note the name and business of my visitor,â he wrote later, describing that meeting for the Associationâs subscribers, âI was struck with the manliness of his person, the breadth of his chest, the openness of his countenance, and the inquietude of his eye.â13 Elsewhere he described Ledyard as being of âmiddling sizeâ, though âremarkably expressive of activity and strength. His manners, though unpolished, were neither uncivil nor unpleasing.â You can hear the affectionate patronage with which the Englishman viewed the brash American.

âI spread the map of Africa before him,â Beaufoy went on, âand tracing a line from Cairo to Sennar [he had clearly forgotten about the deviation to Mecca], and from thence westward in the latitude and supposed direction of the Niger, I told him that was the route, by which I was anxious that Africa might, if possible, be explored.â

Thinking that at last things were going his way, Ledyard admitted that he felt âsingularly fortunate to be entrusted with the adventureâ.14

âWhen will you set out?â Beaufoy asked.

Led on by breezy optimism, the American told Beaufoy he would be ready to leave in the morning.

The Association, however, required more time to prepare for the adventure. Letters of recommendation and credit needed to be arranged and, most important, money had to be raised to pay for the journey. At the inaugural meeting on 9 June the dozen founding Saturdayâs Club members had each committed themselves to paying an annual subscription of five guineas. Within a fortnight, membership had more than doubled: among the new members were Lord Rawdonâs uncle the Earl of Huntingdon, Baron Loughborough, Richard Neave, the Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the West India Merchants, the Prince of Walesâ friend the Duke of Northumberland and two more anti-slavery campaigners. But even if they all paid their subscriptions when asked, which was unlikely, the Association could still only call on £136.10S., and although that may have paid the annual salaries of the servants who ran Banksâ house, it clearly was not going to be enough to fund two separate expeditions into Africa.

Banks had anticipated the problem. On 17 June he had suggested that each of the five Committee members should advance the Association £50 on top of their annual subscriptions. Even then there were not sufficient funds, so the Committee â principally Banks â now agreed to advance the Association a total of £453. Once the money was in place, a number of instructions had to be issued to people such as Mr Baldwin, the British Consul in Alexandria, asking him to act as banker and to honour Ledyardâs letter of credit.

While the practicalities were being sorted out, the traveller was busy preparing for his departure and attending a round of meetings, briefings and dinners. Among them is likely to have been a dinner at the Royal Society Club â the Societyâs social arm â similar to this one described by a passing Frenchman called Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond:

The dishes were of the solid kind, such as roast beef, boiled beef and mutton prepared in various ways, with abundance of potatoes and other vegetables, which each person seasoned as he pleased with the different sauces which were placed on the table in bottles of different shapes. The beefsteaks and the roast beef were at first drenched with copious bumpers of strong beer, casked porter, drunk out of cylindrical pewter pots, which are much preferred to glasses, because one can swallow a whole pint at a draught.

This prelude being finished, the cloth was removed and a handsome and well-polished table was covered, as if it were by magic, with a number of fine crystal decanters filled with the best port, madeira and claret; this last is the wine of Bordeaux. Several glasses, as brilliant in lustre as fine in shape, were distributed to each person and the libations began on a grand scale, in the midst of different kinds of cheese, which rolling in mahogany boxes from one end of the table to the other, provoked the thirst of the drinkers.15

After the cheese, Saint-Fond relates with a sneaking sense of admiration, the serious drinking began.

Ledyard enjoyed all these preparations and revelled in the attention he received in London, some of which clearly touched his vanity. In a letter to his family, he mentions that his portrait had been painted by the Swedish artist Breda and was now hanging at Somerset House, home to both the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Art: the catalogue for the Academyâs annual exhibition that summer lists the portrait and notes that Ledyard âhas undertaken to travel round the world on footâ. In a letter to his cousin, Ledyard described the Association as âa Society of Noblemen & Gentlemen who had for some time been fruitlessly enquiring for somebody that would undertake to travel through the continent of Africa. My arrival,â he added pompously, âhas made it a reality.â16 He seemed to have had an equally inflated opinion of the Associationâs immediate importance, claiming that it already had a membership of two hundred. âIt is a growing thing,â he wrote, â& the King privately promoting & encouraging it will make its objects more extensive than at first thought of. The king has told them that no expense should be spared.â17 There is no evidence that the King ever even mentioned it, but Ledyard clearly believed that money should be forthcoming.

In Paris hoping for a ship to take him to the American north-west, Ledyard had equipped himself with two big dogs and a hatchet, but he had very different plans for Africa. Beaufoy had advanced him thirty guineas as soon as he accepted the mission. Two guineas were spent on his lodgings, the rest going to pay for his wardrobe, which included â6 fine Shirts, 1 Suit of Cloaths [sic], 1 Hat [which cost him a guinea], 1 Pocket Book, 1 Shaving case, 2 pair silk stockings, 2 pair ditto, 1 pair shoes, 1 pair Buckles, 1 pair bag, 1 pair Boots, 1 Watch, Waistcoat & breeches, Ditto ditto black silk, 1 pair black silk stockings, 2 white cravats, 1 Silk Handkerchief. By 17 June he had run up another bill, this time of some £16, and was the proud owner of â2 pair leather pantaloons, new black stock & razor strap, a dozen shirts, 4 hatchets, pair of boots, umbrella, 2 silk handkerchiefsâ.18

Perhaps sensing that Ledyardâs spending was getting out of hand, Banks and Beaufoy met on 26 June to settle his financial arrangements. In all, they were prepared to allow him one hundred guineas to buy clothes and equipment and to get himself to Cairo. In Cairo, Consul Baldwin was authorised to advance £50. This was supposed to be enough to get Ledyard across Africa, although, if Baldwin thought it necessary, he could draw a further £30. The Committee had two reasons for wanting Ledyard to keep his spending to a minimum. For one thing they were short of funds. But more important, they were convinced âthat in such an Undertaking Poverty is a better protection than Wealth, and that Mr. Ledyardâs address [appearance and manner] will be more effectual than money, to open to him a passage to the Interior of Africaâ.19

Around this time, Ledyard wrote to his mother in Connecticut explaining his new commission. âI have trampled the world under my feet, laughed at fear, and derided danger. Through millions of fierce savages, over parching deserts, the freezing north, the everlasting ice, and stormy seas, have I passed without harm. How good is my God ⦠I am going away into Africa to examine that continent. I expect to be absent three years. I shall be in Egypt as soon as I can get there, and after that go into unknown parts.â20 Ledyard was due to leave London on the Dover coach on 30 June. Not being one to let a dramatic moment pass unexploited, that morning he left Beaufoy with a speech guaranteed to stir his sponsors:

I am accustomed to hardships. I have known both hunger and nakedness to the utmost extremity of human suffering. I have known what it is to have food given me as a charity to a madman; and I have at times been obliged to shelter myself under the miseries of that character to avoid a heavier calamity. My distresses have been greater than I have ever owned, or ever will own to any man. Such evils are terrible to bear; but they never yet had power to turn me from my purpose. If l live, I will faithfully perform, in its utmost extent, my engagement to the Society; and if I perish in the attempt, my honour will still be safe, for death cancels all bonds.21

It was a momentous occasion. For Ledyard, this was the fulfilment of his hopes and ambitions, a dangerous journey backed by some of the most important people in Britain and providing an opportunity for him to return to fame and, he hoped, some fortune. For members of the Association, just three weeks to the day after that first meeting in the St Albanâs Tavern they watched their first explorer set off on a geographical mission that they hoped would reveal to them the mysteries of the interior of Africa. Men of science, men of experience whatâs more, they should have known better than to have let their enthusiasm run away with them. The approach they had chosen, bisecting the continent, was hugely ambitious and carried no guarantee of success. Yet they viewed this departure with excitement and imagination, and with a rare humanity: âMuch, undoubtedly, we shall have to communicate [to people in Africa],â Beaufoy was to write, âand something we may have to learn.â22

Ledyard was in Paris by 4 July, for he-sent his compliments to his former patron, the American Consul Thomas Jefferson. Writing from the Hôtel dâAligre on the rue dâOrléans, he explained in a formal note that âhe is now on his way to Africa to see what he can do with that continentâ.23 Jefferson, it seems, was unimpressed that Ledyard had signed up with a British organisation; Ledyard in turn was stung by his mentorâs criticism. This, rather than the cold that Ledyard claimed, may explain why the two men did not meet to celebrate the anniversary of American independence during the week the traveller spent in the French capital. Sailing from Marseilles some days later, Ledyard arrived in Alexandria early in August.

Alexandria looms large in the imagination. Its ancient glory, the reputation that clings to the extravagance of Cleopatra, the plight of its library and the brilliance of its scholars â the geographer Claudius Ptolemy among them â have inspired historians, poets and adventurers. But the port Ledyard sailed into displayed few obvious traces of this glorious past beyond a standing pillar wrongly ascribed to Caesarâs friend Pompey and a fallen obelisk credited to Cleopatra (since removed to London). Alexandria had been the Egyptian capital in the seventh century when conquering Arab armies crossed the Nile, but it had been left to rot in favour of a new settlement at Cairo and its ancient buildings were now buried beneath rubble, used as foundations for meaner houses. What European travellers called âthe Turkish townâ, huddled over the formerly glorious seafront quarter of Alexanderâs city, now contained a mere four thousand people.

The Sultanâs palace stood a little way off from the Turkish town, as did the houses of the few European residents. The only lively part of town was the port, where goods were landed en route to the Red Sea. The size of this transit trade had increased throughout the eighteenth century as British and French interests developed in India and the East. Trade was one of the main reasons why the British Consul, George Baldwin, and his beautiful wife were installed in Alexandria when Ledyard arrived. Another reason was a matter of health. Spring was the season of plague in Egypt, but Alexandria seemed to suffer less severely than Cairo and to rid itself of the disease sooner. In the summer, the season of Ledyardâs arrival, Cairo bubbled under a relentless sun, but in Alexandria one could find relief from the cooling sea breezes.

Baldwin offered the traveller hospitality and accommodation, but Alexandria was not to the Americanâs taste. He described it as a place of âpoverty, rapine, murder, tumult, blind bigotry, cruel persecution, pestilence! A small town built in the ruins of antiquity, as remarkable for its miserable architecture, as I suppose the place once was for its good and great works of that kind.â24 He visited the sights, recovered from his journey and moved on. Seven weeks after leaving England, he was in Cairo.

Carlo Rossetti, the fifty-two-year-old Venetian Consul, was a long-time resident of Egypt. He had made a fortune from assisting cargo being shipped along the overland route between Alexandria and Suez and now wielded great influence, both with Egyptians and foreign governments: among the many posts he held at the time of Ledyardâs arrival was that of British Chargé dâAffaires. Rossetti greeted the new arrival warmly enough, but gave âno very pressing invitationâ for Ledyard to stay with him, so the American settled in one of the cityâs convents, which were usually open to passing Europeans. Rossetti proved to be more generous with his introductions than he had been with his house, and took Ledyard to meet Aga Muhammad, one of Egyptâs power-brokers. This meeting was crucial, for although the entire region as far south as Nubia was officially under the control of Istanbul, it was the Egyptian Pasha who wielded real authority in the south.

Fifteen years earlier, the previous ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Bey Abu Dahab, had expressed surprise, wonder even, at James Bruce wanting to travel up the Nile. When the Pasha asked why he wanted to make the journey, Bruce had answered that he was travelling merely for the pleasure of seeing where the river began. For the Pasha this simply did not make sense. To make the pilgrimage to Mecca or to undertake a journey to trade were things he could understand. But to travel just to look â¦

âYou are not an India merchant?â Bruce reported the Bey as having asked him.

I said, âNo.â

âHave you no other trade nor occupation but that of travelling?â

I said, âThat was my occupation. â

âAli Bey, my father-in-law,â replied he, âoften observed there never was such a people as the English; no other nation on earth could be compared to them, and none had so many great men in all professions, by sea and land: I never understood this till now; that I see it must be so when your king cannot find other employment for such a man as you, but sending him to perish by hunger and thirst in the sands, or to have his throat cut by the lawless barbarians of the desert.â

And all that just to see where the river began.

The King of Sennar had asked Bruce the same question. Bruce had refined his answer to suit local sensibilities and replied that he was travelling to atone for past sins. And how long had he been travelling? Some twenty years, he explained. âYou must have been very young,â the King observed, some of his harem behind him, âto have committed so many sins, and so early; they must all have been with women?â Bruce, with unusual modesty, explained that only some of them were.