Полная версия

The Gates of Africa: Death, Discovery and the Search for Timbuktu

The river known to Europeans by the name of Niger, runs on the South of the kingdom of Cashna, in its course towards Tombuctou; and if the report which Ben Alli heard in that town, may be credited, it is afterwards lost in the sands on the South of the country of Tombuctou.

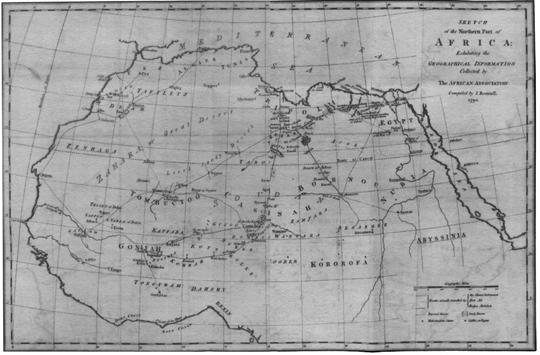

On his map, Rennell marked the known part of the Niger with a continuous line, the speculative part â the run-off into the desert â with a dotted one. But he then went on to assert that âthe Africans have two names for this river; that is, Neel il Abeed, or River of the Negroes; and the Neel il Kibeer, or the Great River. They also term the Nile (that is, the Egyptian River) Neel Shem: so that the term Neel, from whence our Nile, is nothing more than the appellative of River; like Ganges, or Sinde.â25 In this he was completely wrong. The Egyptian Nile is known as the Nil al Kabir; above Khartoum, the western branch of the river is known as the Nil al Abiat (hence his Abeed), or White Nile, the eastern branch along which James Bruce had already explored, being known as the Blue Nile. The word Nil or Neel referred solely to the Nile.

The Sharif Imhammad, Ben Ali and Shabeni had all used a dayâs march as a measure of distance and, in the absence of any readings of longitude or latitude, Rennell had no choice but to use these to create geographical facts. It was a difficult task, perhaps ultimately an impossible one, as he realised when he tried to plot the whereabouts of Timbuktu. But âin using materials of so coarse a kindâ, he apologised, âtrifles must not be regardedâ.26

In what way had this new information changed their understanding of Africa? While Ledyard was rotting in his Cairene grave, Lucas becoming reacquainted with the rituals of court life and Banks busy keeping the minds of government ministers on the fate of the Botany Bay colonists (and while they all watched with horror the unfolding terror in France), Beaufoy sat at his desk in Westminster and drew âconclusions of an important and interesting natureâ.27 Having summed up the Associationâs advances and dwelled on some of the minutiae of the facts, he turned to something he knew would touch his audience directly: the British Grand Tourist, he suggested, might consider âexchanging the usual excursion from Calais to Naples, for a Tour more extended and importantâ.28 The location of this place? None other than Fezzan. Here, he assured his readers, the amateur of archaeology would find fulfilment and the lover of Nature could discover much that was so far unknown in Europe. All of which was probably true, only first the traveller had to find a way of reaching Fezzan, something Lucas had failed to do.

Rennellâs map of Africa, 1790

For the more adventurous tourist, the possibilities seemed endless, even if the destinations were unknown:

The powerful Empires of Bornu and Cashna will be open to his investigation; the luxurious City of Tombuctou, whose opulence and severe police attract the Merchants of the most distant States of Africa, will unfold to him the causes of her vast prosperity; the mysterious Niger will disclose her unknown origin and doubtful termination; and countries unveiled to ancient and modern research will become familiar to his view.29

It was wishful thinking, of course. How was a Grand Tourist to swap Naples for central Sahara when Rennell was still struggling to locate with certainty Borno, Katsina or any of the other powerful empires? And how was an English lord or gentleman to succeed when a traveller of John Ledyardâs experience, who had sailed the world with Cook and crossed Siberia alone, had managed to go no further than Cairo and Simon Lucas hardly left sight of the coast?

The Associationâs first resolution, drafted by Beaufoy that summer day back in 1788, stated that âno species of information is more ardently desired, or more generally useful, than that which improves the science of Geographyâ.30 Their area of enquiry was clearly fixed on the interior of the northern half of Africa, in particular the River Niger, the east â west trans-continental caravan routes and the whereabouts of Timbuktu. But Beaufoy now extended the bounds of the Associationâs interests from geography and history to trade. And given that the flag followed trade just as much as trade followed the flag, he was also moving the Association into the realm of politics.

Beaufoy concluded by laying out the commercial possibilities the Associationâs researches had exposed. âOf all the advantages to which a better acquaintance with the Inland Regions of Africa may lead, the first in importance is, the extension of the Commerce, and the encouragement of the Manufactures of Britain ⦠One of the most profitable manufactures of Great Britainâ,31 he went on, was firearms. These were currently traded along the coast. The rulers of the coastal states had effectively stopped the movement of weapons into the interior for the obvious reason that guns gave them an edge over their more powerful inland neighbours. If their rivals were able to buy European-made weapons, the coastal states would be overrun. British traders, Beaufoy seemed to be suggesting, need have no scruples about arming both sides in this conflict, nor about disturbing the balance of power. Perhaps he believed that this might in some way stop the flow of slaves from the interior to the coast.

As well as musing on the sale of firearms, Beaufoy drew some larger conclusions about the African trade. Merchants from Morocco, Tripoli, Egypt and elsewhere, he noted, went to the considerable expense of mounting caravans and making extraordinary journeys across the Sahara, with all the costs and dangers that this entailed, and were still able to turn a good profit. Millions of pounds were mentioned. And here the idea first suggested by Ben Ali reappears. Imagine, Beaufoy went on, how much profit British traders might make if they cut inland from the coast south of the Sahara, much less than half the journey of the northern African traders. This, of course, ignored the fact that no European he knew of had made that journey and lived to tell the tale. âAssociations of Englishmen should form caravans, and take their departure from the highest navigable reaches of the Gambia [River], or from the settlement which is lately established at Sierra Leone.â There would, he knew, be setbacks, as there always are with new ventures. But consider the market: appearing to pluck a figure from the air, for he had nothing more substantial to base it on, he estimated the population in the interior, of Katsina, Borno, Timbuktu and all those other places Rennell had recently plotted on his map, at probably more than one hundred millions of peopleâ.32 âThe gain would be such as few commercial adventures have ever been found to yield.â33

After all these exhortations, it comes as no surprise that the Associationâs next missionary was sent to find a route between the Gambia River, the Niger and âluxuriousâ, gold-plated Timbuktu.

* Lettson studied medicine under Sir William Fordyce, one of the Associationâs original members. He went on to found the Royal Humane Society and the Philosophical Society of London.

* Sansom later served as Deputy Chairman of the Sierra Leone Company, the philanthropic organisation that helped to establish a settlement for freed slaves in West Africa in 1787.

6

The Gambia Route

âOn Saturday the African Club [the Committee] dined at the St Albanâs Tavern. There were a number of articles produced from the interior parts of Africa, which may turn out very important in a commercial view; as gums, pepper, &c. We have heard of a city ⦠called Tombuctoo: gold is there so plentiful as to adorn even the slaves; amber is there the most valuable article. If we could get our manufactures into that country we should soon have gold enough.â

Sir John Sinclair, 17901

IN 1782, six years before the Association was formed, Sir Joseph Banks found himself faced with a situation of the utmost delicacy. A Fellow of the Royal Society, a wealthy chemist by the name of John Price, announced that he had found a way of converting mercury into gold. Priceâs claim caused a sensation, not least because it appeared to be verified by witnesses of great character: he had conducted the experiment at his Surrey laboratory, where, in the presence of their lordships Palmerston, Onslow and King, he produced a yellow metal that was proved, upon testing, to be gold. When word got out, Price quickly became a national hero, fêted throughout the land; Oxford University, perhaps a little opportunistically, even offered him an honorary degree. Barely audible over the clamour and adulation, Sir Joseph and some of his colleagues at the Royal Society announced that they simply didnât believe him. Rather than draw more attention to the man, the Fellows decided to do nothing, in the hope that he would soon be exposed or forgotten. The opposite happened. Price published an account of his experiment, although not the actual formula for making the precious metal, and the book quickly sold out. Banks decided this story had gone far enough, and asked its author to be so kind as to repeat the experiment for the scrutiny of the Royal Society. Price agreed and, on the appointed day, welcomed three eminent Fellows into his lab. Instead of alchemy, they witnessed a different sort of experiment: Price swallowed a phial of poison and died before their eyes.

The Price episode was unusual but by no means unique. In an age of trial and error, when some scientists were making such huge advances, it seemed as though anything was possible, even the creation of gold from base metal. In such a climate, the idea of sending explorers off to an area that others had already visited and asking them to locate towns, rivers and goldfields that were known to exist must have seemed a low-risk adventure. And yet, for their third mission, the Association reigned in some of its ambition. The grand plan of bisecting the northern half of Africa, of sending one explorer to cross it from east to west and another from north to south, was abandoned. The next geographical missionary was to follow up the Hajj Shabeniâs suggestion and cut a passage through from the Atlantic coast to the Niger River. This plan was more specific than the previous one and, the Committee must have reckoned, more likely to succeed. Their traveller would head up the Gambia River and cut inland to the kingdoms of Bondo and Bambuk, both bywords for gold and lying in an area in which the French had been trying to open trade with the Atlantic. Beyond Bambuk lay the route to Timbuktu, a place where âgold is ⦠so plentiful as to adorn even the slavesâ, Committee member Sir John Sinclair noted, echoing the reports of earlier centuries. But if deciding on new routes of exploration was easy, choosing the right man for the job was not.

There was no shortage of volunteers â Banksâ archive is littered with applications â but the Committee had been criticised for their first choice of missionaries and also for the routes they had chosen, so this time they were going to take more care. In March 1789, James Bruce had warned Banks about Ledyard: âI am afraid,â he wrote from his family seat in Kinnaird, Scotland, âyour African or rather Nubian traveller will not answer your expectations ⦠He is either too high or too low; for he should join the Jellaba at Suakim ⦠or else he should have gone to Siout or Monfalout in Upper Egypt from Cairo, and, having procured acquaintance and accommodations there, set out with the great Caravan of Sudan, traversing first the desert of Selima to Dar Four, Dar Selé, and Bagirma, so on to Bournu, and down to Tombucto to the Ocean at Senega or the Gambia.â2 Harsh, perhaps, but history proved him right.

Not everyone was so critical of Ledyard, however. Thomas Jefferson, his patron in Paris, continued to refer to his âgeniusâ, while the opinion-making Gentlemanâs Magazine, considering his mission in its issue of July 1790, thought that âSuch a person as Mr. Ledyard was formed by Nature for the object in contemplation; and, were we unacquainted with the sequel [his death in Cairo], we should congratulate the Society in being so fortunate as to find such a man for one of their missionaries.â But then in January 1792, W.G. Browne, a traveller we shall meet in the field in the next chapter, wrote that âLedyard, the Man employed by the society on the Sennar expedition, was a very unfit person; and, thoâ he had lived, would not have advanced many leagues on the way, if the judgement of people in Egypt concerning him be credited.â3

Lucas attracted just as much criticism. When news of his failure to get beyond the Libyan coast reached Tangier, James Matra, the Consul, wrote to Banks, âI am sorry for Lucasâ miscarriage, but his expedition has ended as ever I feared it would. He is nothing but a good natured fellow. It is very certain that a Moorish education [which Lucas had had as a slave to the Emperor of Morocco] plays the devil with us. Were you to take one from the first stock of Heroes and bring [him] up here, timidity would be the most certain though by far not the worst consequence of it.â4 Another of the Associationâs missionaries, meeting Lucas several years later, wrote, âI donât know if the Committee believes his excuses for his returning to England, or if they give them so little a credit as I do myself â¦â5

The obvious conclusion to be drawn in 1790 was that in their haste to get their first two missions off to Africa, the Committee had chosen men who were either inappropriate for the task they had been given, as in the case of Lucas, or insufficiently prepared, as could be said of Ledyard. It was clear that more than languages, which had been Lucasâ strength, or travel experience, which had recommended Ledyard, were needed to crack open the African shell. But then, consider the problems the Associationâs missionaries faced. Apart from the fact that they were uncertain of where they were going and of what they would find when they got there, they needed to have a great facility with languages â take a trip along the River Niger in Mali now and you will find your boatman speaking at least half a dozen quite distinct languages or dialects in the course of a normal day, including Mandekan, Soninke, Wolof, Fulani and Songhay. They also needed extraordinary physical strength and what Banks would have called rude health. After all, they were being sent to an area that later came to be known as the white manâs grave. A long list of preventatives are recommended today to protect travellers in the region against cholera, yellow fever, typhoid, meningitis, polio, tetanus, diphtheria, hepatitis A and B, rabies and malaria, none of which had even been identified in the late eighteenth century. Diplomacy was another essential skill for the Associationâs travellers. Throughout Africa there was great suspicion of Europeans and Americans. Why were they there? Were they preparing for an invasion? Were they going to take over local trade? Was it gold that drew them so far from home? Certainly no one in West Africa was going to be convinced by the sort of explanation Bruce and Ledyard offered in Cairo, that they were travelling out of curiosity, just to see where rivers rose, to know what lay across deserts. European involvement in the slave trade had revealed the brutish side of the Christian spirit and had shown how easily visitors could become raiders. If there had ever been any romantic speculation about white men in West Africa, it was long gone.

Miraculously, in the summer of 1790 the Committee received an offer of âservicesâ from someone who seemed to possess just about all of the experience and qualities they now knew they wanted. In July 1788, Banksâ friend and colleague at the Royal Society, the lawyer Sir William Musgrave, had written to suggest that a man by the name of Daniel Houghton might be of use to the Association. Nothing came of it at the time because Ledyard and Lucas had already been commissioned. But Houghton kept his eye on the Associationâs progress, and when two years later he heard that the Committee were planning a new expedition, he was quick to repeat his offer.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.