полная версия

полная версияMy Studio Neighbors

A QUEER LITTLE FAMILY ON THE BITTERSWEET

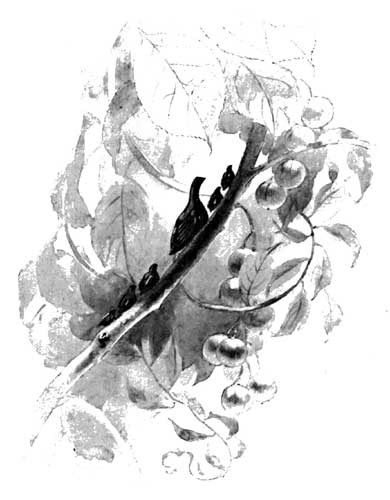

IN a recent half-hour's relaxation, while comfortably stretched in my hammock upon the porch of my country studio, I was surprised with a singular entertainment. I soon found myself most studiously engaged. Entwining the corner post of the piazza, and extending for some distance along the eaves, a luxuriant vine of bittersweet had made itself at home. The currant-like clusters of green fruits, hanging in pendent clusters here and there, were now nearly mature, and were taking on their golden hue, and the long, free shoots of tender growth were reaching out for conquest on right and left in all manner of graceful curves and spirals. Through an opening in this shadowy foliage came a glimpse of the hill-side slope across the valley upon whose verge my studio is perched, and as my eye penetrated this pretty vista it was intercepted by what appeared to be a shadowed portion of a rose branch crossing the opening and mingling with the bittersweet stems. In my idle mood I had for some moments so accepted it without a thought, and would doubtless have left the spot with this impression had I not chanced to notice that this stem, so beset with conspicuous thorns, was not consistent in its foliage. My suspicions aroused, I suddenly realized that my thorny stem was in truth merely a bittersweet branch in masquerade, and that I had been "fooled" by a sly midget who had been an old-time acquaintance of my boyhood, but whom I had long neglected.

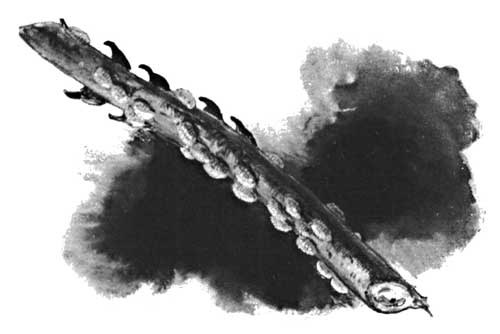

Every one knows the climbing-bittersweet, or "waxwork" (Celastrus scandens), with its bright berries hanging in clusters in the autumn copses, each yellow berry having now burst open in thin sections and exposed the scarlet-coated seeds. Almost any good-sized vine, if examined early in the months of July and August, will show us the thorns, and more sparingly until October, and queer thorns they are, indeed! Here an isolated one, there two or three together, or perhaps a dozen in a quaint family circle around the stem, their curved points all, no matter how far separated, inclined in the same direction, as thorns properly should be. Let us gently invade the little colony with our finger-tip. Touch one never so gently and it instantly disappears. Was ever thorn so deciduous? And now observe its fellows. Here one slowly glides up the stem; another in the opposite direction; another sideways. In a moment more the whole family have entirely disappeared, as if by hocus-pocus, until we discover, by a change of our point of view, that they have all congregated on the opposite side of the stem, with an agility which would have done credit to the proverbial gray squirrel.

This animated thorn is about a quarter of an inch long, and dark brown in color, with two yellowish spots on the edge of its back.

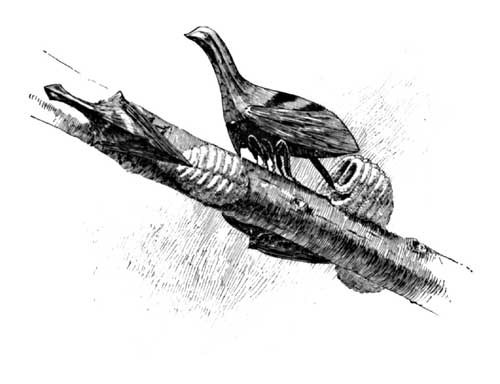

Nor is this all the witchery of this bittersweet thorn. It is well worth our further careful study. Seen collectively, the thorny rose branch is instantly suggested, but occasionally, when we observe a single isolated specimen, especially in the month of July, he will certainly masquerade in an entirely new guise. Look! quick. Turn your magnifier hither on this green shoot. No thorn this. Is it not rather a whole covey of quail, mother and young creeping along the vine? Who would ever have thought of a thorn! Turning now to our original group, how perfectly do they take the hint, for are they not a family of tiny birds with long necks and swelling breasts and drooping tails, verily like an autumn brood of "Bob Whites"?

A Bittersweet Covey

But the little harlequin is as wary a bird as he was a thorn! No sooner do we touch his head with our finger than with an audible "click" he is off on a most agile jump, which he extends with buzzing wings, and is even now perhaps aping a thorn among a little group of his fellows somewhere among the larger bittersweet branches.

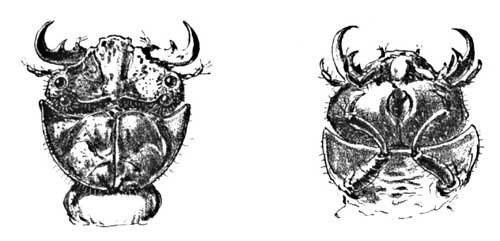

It is only as we capture one of the little protean acrobats between our finger-tips and examine him with a magnifier that we can really make "head or tail" of his queer anatomy. Even thus enlarged it is difficult to get entirely rid of the idea of a bird. I have shown a group of the insects in various attitudes, the position of the eyes alone serving as a starting-point for our comprehension of his singular make-up. The tall neck-like or thorn-like prominence is then seen to be a mere elongated helmet, which is prolonged into a steep angle behind, so as to cover the back of the creature like a peaked roof, a feature from which the scientific name of this particular group of insects is derived, Membracis, meaning sharp-edged, the sides of the slope being covered by the close-fitting wings, which, though apparently compact with the body of the insect, are nevertheless always available for instant and most agile flight. We now discover two pairs of stout legs just beneath the edge of the wings, a third more slender pair being concealed behind, ready for immediate use in association with these buzzing wings when the whim of the midget prompts it to leap.

Flushing the Game

This insect is the tree-hopper, and is but one of many equally curious and mimetic species to be found among the smaller branches of various trees and shrubs.

Our largest membracis is to be seen—with difficulty—on the terminal twigs of the locust-tree, its outlines so exactly imitating the thorny growths of the branch as to escape detection even by the closest scrutiny. Another remarkable species is a protégé of the oak, so closely simulating the warty bark of the smaller branches upon which it is found that our eyes may rest upon it repeatedly without recognizing it. The life history of these singular insects is quite similar, and is soon told. The membracis belongs to the tribe of "Bugs," Hemiptera, which implies that it possesses a beak instead of jaws, by which it sucks the sap of plants, precisely like the aphis, or plant-louse. This tiny beak we can readily distinguish bent beneath the body of our bittersweet hopper. Inserting it deep into the succulent bark, the parasite remains for hours as motionless as the thorn it imitates, the lower outline of its body hugging close against the bark. The curious suggestion of the thorn is produced not only by the outline, but by the curious fact that the hopper never sits across the twig, but always in the direction of its length; and, what is more, the projecting point of the thorax is always directed towards the end of the branch, or direction of growth. It is no easy thing even for the casual botanist to determine this nice point in a given segment of a bittersweet branch placed in his hand, the position of the chance leaf or leaf scar being his only guide. But the Membracis binotata rarely—indeed never, so far as I have examined—makes a mistake. Thus the wandering spray of bittersweet, recurve and twist upon itself as it may, will always disclose the little hopper or colony of them headed for its tip.

Specimen Twig

But I have omitted to mention one singular feature which is the usual accompaniment of my group of hoppers, and is, indeed, the most conspicuous sign of their presence on any given shrub. In the cut below I have indicated a short section of a bittersweet branch as it commonly appears, the twig apparently beset with tiny tufts of cotton, occasionally so numerous as to present a continuous white mass, usually on the lower side of the branch, where its direction is horizontal. They are thus easily seen from below, and a closer examination will always reveal one or more of the black animated thorns in their immediate vicinity, suggesting the responsible source. These tufts are pure white, a little over an eighth of an inch in length, and semicircular in vertical outline. The natural presumption is the idea of maternity, the mother hopper guarding her bundles of white eggs, or her infant hoppers, perhaps, snugly tucked up in their downy swaddling-clothes. But a closer examination completely dispels this illusion. Instead of the supposed fluffy cotton, we now discover the white substance to be of firm though somewhat sticky consistency, its surface, moreover, beautifully ridged from base to summit in parallel rounded flutings, which meet and interfold like a braid along the summit. If with a sharp knife we now cut downward through and across the mass, we find our tuft to be a mere frothy shell containing two hollow compartments, with a thin central partition extending through the whole length of the cavity. But there is no sign of an egg or other life to be disclosed anywhere, either in its substance or its concealment. What, then, is the office of this tiny fragile house of congealed foam, with its snowy aerated structure, its double arched chambers, its corrugated walls and ceilings, and missing tenant or host? Such was the riddle which it propounded to me, and guided by some previous knowledge of the habits of allied insects, I was soon enabled to witness a solution of at least a part of its mystery.

This little thorn-like tree-hopper and all of its queer harlequin tribe are near relatives to the buzzing cicada, or harvest-fly, whose whizzing din in the dog-days has won it the popular misnomer of "locust."

To the average listener this insect is a mere "wandering voice and a mystery," and its singular form, wide prominent eyes, glassy wings, and double drums are always a surprise to the tyro who first identifies the grotesque as his well-known "locust." Its musical accomplishments during this brief period of its life are known to all, but few have cared to interest themselves in the early history of the singer, ere it perfected its musical resources "for the delight of man." But the naturalist, and especially the arboriculturist and fruit-grower, know to their cost of other tricks of the cicada, or rather of Mrs. Cicada, immortalized by Zenarchus the Rhodian as his "noiseless wife"—

"Happy the cicadas' lives,Since they all have noiseless wives."I have alluded to the egg of the cicada "inserted in the bark of a twig." This act is accomplished by a knife-like ovipositor, which literally gouges a deep gash into the tender wood of various twigs, a number of the eggs being implanted in its depths, often causing the death of the branch. Shortly after hatching, the young cicadas leap for the ground, and burrowing beneath the surface, remain for a period varying from three to seventeen years, according to the species, to complete their transformations. Now the habits of my little tree-hopper are somewhat modelled after its big cousin. Knowing that the little insect was provided with a keen-edged ovipositor, and was in the habit of thrusting its tiny eggs beneath the bark, and realizing, too, that these strange tufts were of course in some way connected with the maternal instinct, I was led to investigate. Selecting a branch where the tufts and hoppers seemed most prolific, I brought my magnifying-glass to bear upon them at a respectful distance. Was ever actual thorn more motionless or non-committal than most of these?—their under surfaces hugging close against the bark, their telltale feet closely withdrawn, and all their pointed helmets inclined in the same parallel direction. One after another of the sly little family was examined without a revelation. Not until I had reached the upper limit of the group did I get any encouragement. Here I discovered one of the midgets in a new position, its pointed helmet inclined farther downward, and its other extremity correspondingly raised, so that I could see beneath its body. I now observed what at first appeared to be the hind leg of the farther side of the body protruding beneath, but in another moment noted my error, and saw that its sharp point had penetrated the bark, into which it soon sank quite deeply, and I realized that the ovipositor was now conducting its tiny eggs into the cambium layer of the bark. Without waiting for this particular individual to finish her labors, which might be extended for hours for aught I knew, I turned my glass upon its nearest neighbor, and a most accommodating specimen she proved, disclosing all the mysteries of the little froth house, its strange material, and unique method of construction. What I saw reminded me irresistibly of the technique of the cake-frosting art of the fancy baker, with its flowing tube of white condiment, and its following tracery of questionable design in high relief. This accommodating specimen had apparently just completed her egg-laying, or had perhaps just filled one nest; and while her attitude was precisely similar to that of her neighbor, I noticed a tiny ball of glistening froth at the tip of the ovipositor. This was attached to the bark by a touch, and from this starting-point the construction of the glistening house was continued, the apex of the ovipositor pouring out its endless puffy roll of aerated cement, which seemed to set as soon as laid.

And what a convenient implement this for a froth-house builder who is compelled to work behind her back—mortar-feeder, trowel, darby, compass, and level all in one! Beginning with the first touch of the cement, the flowing point describes a very small half-circle to the right, again meeting the bark. It is now carried inward and upward, describing a very close circle with scarcely any space intervening, a similar circle being repeated on the left side. A new tier is then begun in the same manner, only this time a little larger in the sweep, and leaving a perceptible opening at the right as the central wall is carried upward with slightly decreased material. Returning down the central wall again, the white coil is carried to the left along the bark, and up again on the other outer edge, until it once more meets its fellow at the ridge-pole, where the two coils appear to interlock as in a braid. And thus the little builder continues, enlarging the cavity with each circuit, until the full height is reached, and then decreasing proportionately until the glistening braided dome is tapered off again against the bark.

Building Froth-tent

Now what is the object of this frothy pavilion? The life history of the insect, in contrast to that of the cicada, will perhaps throw a little light on that question. In the cicada, as I have shown, the eggs are inserted in the bark, but the young, hatching about six weeks later, immediately forsake the parent tree and enter the ground. But the young of our bittersweet membracis are not thus fickle, the entire life of the insect being spent on the plant. Moreover, its eggs are laid in late summer, and do not hatch until the following spring. What, then, is this canopy of the tree-hopper but the provision of a thoughtful mother, a pavilion about her offspring as a shelter through the winter storms? In early July the tiny hoppers emerge from their egg-cases, and presumably creep out from their luminous domicile, and later on in the season these broods of varying numbers and all sizes are to be seen among the young stems of the plant, their beaks inserted, their pointed heads invariably in the same direction—towards the top of the branch. Even though in flight one of the midgets is seen to alight in violence to the rule, he instantly recognizes his mistake, and quickly glides round to the orthodox position.

This curious insect is chiefly confined to the bittersweet, though he is occasionally found in the company of a much bigger cousin of his on the branches of the locust, where these same telltale corrugated frothy pavilions are often seen to clothe the young twigs in their white tufts, the similar product of the larger species, which thus also presumably spends its entire life upon the locust-tree.

THE WELCOMES OF FLOWERS

It is now some thirty years since the scientific world was startled by the publication of that wonderful volume, "The Fertilization of Orchids," by Charles Darwin; for though slightly anticipated by his previous work, "Origin of Species," this volume was the first important presentation of the theory of cross-fertilization in the vegetable kingdom, and is the one that is primarily associated with the subject in the popular mind. The interpretation and elucidation of the mysteries which had so long lain hidden within those strange flowers, whose eccentric forms had always excited the curiosity and awe alike of the botanical fraternity and the casual observer, came almost like a divine revelation to every thoughtful reader of his remarkable pages. Blossoms heretofore considered as mere caprices and grotesques were now shown to be eloquent of deep divine intention, their curious shapes a demonstrated expression of welcome and hospitality to certain insect counterparts upon whom their very perpetuation depended.

Thus primarily identified with the orchid, it was perhaps natural and excusable that popular prejudice should have associated the subject of cross-fertilization with the orchid alone; for it is even to-day apparently a surprise to the average mind that almost any casual wild flower will reveal a floral mechanism often quite as astonishing as those of the orchids described in Darwin's volume. Let us glance, for instance, at the row of stamens below (Fig. 1), selected at random from different flowers, with one exception wild flowers. Almost everybody knows that the function of the stamen is the secretion of pollen. This function, however, has really no reference whatever to the external form of the stamen. Why, then, this remarkable divergence? Here is an anther with its two cells connected lengthwise, and opening at the sides, perhaps balanced at the centre upon the top of its stalk or filament, or laterally attached and continuous with it; here is another opening by pores at the tip, and armed with two or four long horns; here is one with a feathery tail. In another the twin cells are globular and closely associated, while in its neighbor they are widely divergent. Another is club-shaped, and opens on either side by one or more upraised lids; and here is an example with its two very unequal cells separated by a long curved arm or connective, which is hinged at the tip of its filament; and the procession might be continued across two pages with equal variation.

Fig 1. A Row of Stamens

As far back as botanical history avails us these forms have been the same, each true to its particular species of flower, each with an underlying purpose which has a distinct and often simple reference to its form; and yet, incredible as it now seems to us, the botanist of the past has been content with the simple technical description of the feature, without the slightest conception of its meaning, dismissing it, perhaps, with passing comment upon its "eccentricity" or "curious shape." Indeed, prior to Darwin's time it might be said that the flower was as a voice in the wilderness. In 1735, it is true, faint premonitions of its present message began to be heard through their first though faltering interpreter, Christian Conrad Sprengel, a German botanist and school-master, who upon one occasion, while looking into the chalice of the wild geranium, received an inspiration which led him to consecrate his life thence-forth to the solution of the floral hieroglyphics. Sprengel, it may be said, was the first to exalt the flower from the mere status of a botanical specimen.

This philosophic observer was far in advance of his age, and to his long and arduous researches—a basis built upon successively by Andrew Knight, Köhlreuter, Herbert, Darwin, Lubbock, Müller, and others—we owe our present divination of the flowers.

In order to fully appreciate this present contrast, it is well to briefly trace the progress, step by step, from the consideration of the mere anatomical and physiological specimen of the earlier botanists to the conscious blossom of to-day, with its embodied hopes, aspirations, and welcome companionships.

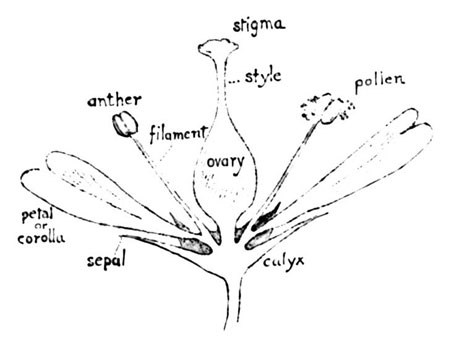

Most of my readers are familiar with the general construction of a flower, but in order to insure such comprehension it is well, perhaps, to freshen our memory by reference to the accompanying diagram (Fig. 2) of an abstract flower, the various parts being indexed.

Fig. 2. The Parts of a Flower

The calyx usually encloses the bud, and may be tubular, or composed of separate leaves or sepals, as in a rose. The corolla, or colored portion, may consist of several petals, as in the rose, or of a single one, as in the morning-glory. At the centre is the pistil, one or more, which forms the ultimate fruit. The pistil is divided into three parts, ovary, style, and stigma. Surrounding the pistil are the stamens, few or many, the anther at the extremity containing the powdery pollen.

Although these physiological features have been familiar to observers for thousands of years, the several functions involved were scarcely dreamed of until within a comparatively recent period.

In the writings of ancient Greeks and Romans we find suggestive references to sexes in flowers, but it was not until the close of the seventeenth century that the existence of sex was generally recognized.

Fig. 3. Historical Series, Showing the Progress of Discovery of Flower Fertilization

In 1682 Nehemias Grew announced to the scientific world that it was necessary for the pollen of a flower to reach the stigma or summit of the pistil in order to insure the fruit. I have indicated his claim pictorially at A (Fig. 3), in the series of historical progression. So radical was this "theory" considered that it precipitated a lively discussion among the wiseheads, which was prolonged for fifty years, and only finally settled by Linnæus, who reaffirmed the facts declared by Grew, and verified them by such absolute proof that no further doubts could be entertained. The inference of these early authorities regarding this process of pollination is perfectly clear from their statements. The stamens in most flowers were seen to surround the pistil, "and of course the presumption was that they naturally shed the pollen upon the stigma," as illustrated at B in my series. The construction of most flowers certainly seemed designed to fulfil this end. But there were other considerations which had been ignored, and the existence of color, fragrance, honey, and insect association still continued to challenge the wisdom of the more philosophic seekers. How remarkable were some of those early speculations in regard to "honey," or, more properly, nectar! Patrick Blair, for instance, claimed that "honey absorbed the pollen," and thus fertilized the ovary. Pontidera thought that its office was to keep the ovary in a moist condition. Another botanist argued that it was "useless material thrown off in process of growth." Krunitz noted that "bee-visited meadows were most healthy," and his inference was that "honey was injurious to the flowers, and that bees were useful in carrying it off"! The great Linnæus confessed himself puzzled as to its function.

For a period of fifty years the progress of interpretation was completely arrested. The flowers remained without a champion until 1787, when Sprengel began his investigations, based upon the unsolved mysteries of color and markings of petals, fragrance, nectar, and visiting insects. The prevalent idea of the insect being a mere idle accessory to the flower found no favor with him. He chose to believe that some deep plan must lie beneath this universal association. At the inception of this conviction he chanced to observe in the flower of the wild geranium (G. sylvaticum) a fact which only an inspired vision could have detected—that the minute hairs at the base of the petal, while disclosing the nectar to insects, completely protected it from rain. Investigation showed the same conditions in many other flowers, and the inference he drew was further strengthened by the remarkable discovery of his "honey-guides" in a long list of blossoms, by which the various decorations of spots, rings, and converging veins upon the petals indicated the location of the nectar.