полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 6, 1921

Furthermore, the force which operates in causing men to move generally presents one of two aspects, viz., attractive and repellent. "Men are either drawn or driven to break the ties which bind them to their native locality." Again, the causes of migration are classified as positive advantages and satisfactions, and negative discomforts and compulsions. The causes of the repellent or negative type exist in the environment of the locality to which man is already attached. They, therefore, are much more important than the others, because, despite the inducements of another locality which may be opened to him, it is the tendency of man to remain where he is, if he is contented. These forces must produce dissatisfaction with existing conditions in order to induce man to move. The causes of the attractive or positive type, on the other hand, are in a foreign environment, and operate often by stimulating dissatisfactions through comparison. They must, before movement can be induced, show that conditions in the new locality are superior to those in the home environment. "Thus, in almost every case of migration one is justified in looking for some cause of a repellent nature, some dissatisfaction, disability, discontent, hardship, or other disturbing condition;" and, likewise, some positive advantage, satisfaction, prospect of contentment, or other favorable condition. Therefore, it goes almost without saying that the study of this subject of Negro migration will show that these two types of forces or causes were also present in this recent movement.

Again, these repellent or negative conditions which cause men to move may arise in any of the various interests of human life, and may be classified as economic, political, social, and religious. Of these "the economic causes of migration are the earliest and by far the most important. They arise in connection with man's effort to make his living and concern all interests which are connected with his productive efforts. They are disabilities or handicaps which affect his pursuit of food, clothing and shelter, as well as the less necessary comforts of life. These are vital interests and any dissatisfaction connected with them is of great weight to men."

Inasmuch as the economic causes of migration are primal and most important, and since like causes played such a large part in giving rise to this recent movement, it might be well to pause here to enumerate some of these causes, and to note briefly the nature of the same. In the first place, a migration may occur because of permanent infertility of the soil, harsh climate, or a dearth of natural resources which may perpetually intensify man's struggle for existence. In the next place, it may be due to temporary natural calamities such as drought, famine, flood, extreme seasons and so on. This latter set of causes, as will be seen later on, were prominent factors in the recent Negro movement from the South to the North. Again, people may be forced to move because of serious underdevelopment of the industrial arts which may make living hard by limiting the productive power of the people or by retarding them in the struggle for trade. Finally, migration may be due to overpopulation—a condition in which the population of a country has increased to such a degree that there are too many people in proportion to the supporting power of the environment.

As has just been intimated, the causes of migration are fourfold, namely, economic, political, social, and religious. Because of this it must not be thought, however, that these causes are separate and distinct; but it should be understood that they overlap each other and exist almost always in conjunction. In any migration two or more of them will be found present. For example, it is very difficult to find cases in which social causes alone account for a migration. They often, nevertheless, act as a contributory factor to a movement. The economic causes are by far the most important and universal; but behind them are frequently other causes. "Political maladjustments often express themselves through economic or social disabilities, religious differences through economic and social limitations, etc." In short, it may be said that the motives of migration may be due to a complication of causes. This may be well illustrated by the study of the recent Negro migration in which it will be found that this movement was occasioned by a number of interacting economic, social, and, to a small extent, political forces.

As there are types of forces or causes giving rise to migration, there are likewise types of migration. These are the following four: invasion, conquest, colonization and immigration. Besides these four main types of movement there are other less important forms which deserve notice. They are of two kinds, namely, forced forms of migration, and internal or intra-state migration of peoples. The former occurs (1) when people are expelled from a country because of non-conformity to the established religion; (2) when they are compelled by actual force to leave one place and go to another, as in the case of the importation of Negroes from Africa to the United States to become slaves; and (3) when people are subjected to banishment from a country as a form of punishment for crime. The internal or intra-state movement is that which is going on all the time in most civilized countries, and which is usually a phenomenon of non-importance; but when it involves large masses of people, moving in certain well-defined directions, with a community of motives and purposes, it becomes of great interest and significance and deserves to be classed with the other great movements of peoples. One good example of this is the westward movement of the people of the United States during the early decades of the past century. Another which might be rightly classed as such is the recent large Negro migration which is under consideration in this essay.

The subject of migration in general is capable of very lengthy treatment, but as this is not our purpose here we shall terminate this discussion at this juncture. In this preliminary survey the aim has been to try to show, though in an exceedingly brief manner, the meaning and significance of migration as a factor in the human struggle for existence; the distinction between migration and the earliest movements of primitive man; the types of forces which figure in any migration; and the various forms in which a migration may occur. This has been done with the further intention of endeavoring to imbue the mind at the outset with the idea that this Negro migration is not very radically different from the past movements of civilized man, and that, like them, it occurred in obedience to certain laws which were operating in the environment of the migrants. If this object can be accomplished, little doubt is entertained that it will do much toward affording a clearer and more comprehensive view of the movement than could be otherwise obtained.

Chapter II

PREVIOUS NEGRO MOVEMENTS

Among the many who have written concerning this exodus one finds that not a few of them have been prone to emphasize the fact that in this recent movement the Negroes suddenly developed within themselves a desire to move, thus implying that migration is not controlled by certain economic and social laws, and that this movement was an entirely new social phenomenon. Disregarding for the present the first assumption, and directing attention to the second, the writer holds that the latter must have sprung from the fact that no account was taken of the past economic and social history of the Negroes; for a study in that direction would have shown that ever since the time of their emancipation the Negroes have shown a tendency to migrate.444 That this has been the case a number of instances will demonstrate.

Shortly after emancipation there occurred slow and confused movements of the Negro population which covered a period of several years. During his enslavement the Negro could hardly do anything without the will and consent of his master; he had not the liberty to order and direct his life as he chose. When, therefore, he was suddenly transformed from this state to that of freedom, the first thing he did was to put this freedom to test by moving about. Consequently he drifted from place to place and at the same time changed his name, employment, and even his wife. Many also devoted much of their time to hunting while they were awaiting Federal Government assistance in the form of land and mules. Emancipation meant to them not only freedom from slavery but freedom from responsibility as well. Thus during their early years of liberty large numbers of Negroes moved about almost aimlessly and thoughtlessly and made their way especially to the towns, cities and Federal military camps.445

There was, moreover, a considerable movement of the Negro population toward the southwestern part of the United States. It was very slow and was in operation between 1865 and 1875, when the expansion of the numerous railway systems gave rise to a great number of land speculators who did much to induce men to go West and settle on the land. Their appeals greatly aroused the Negroes who had reasons for a change of abode. This movement was at first composed of individuals; but later on it became a group movement. In this migratory stream which flowed southwestward were 35,000 Negroes, who came largely from South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.446

Again, in 1879, a large number of Negroes made a rush to Kansas.447 This movement was due for the most part to agricultural depression in parts of the South, but was precipitated greatly by the activities of a host of petty Negro leaders who had sprung up in all parts of the South during the Reconstruction period. This exodus began early in March and continued till May. The estimated number of migrants was between 5,000 and 10,000; but there were thousands of others who had planned to migrate, but were deterred from doing so because of the news of the misfortunes which befell those who actually moved. The majority of those who left the South were from Louisiana and Mississippi. In this migration the Negroes left their homes when the weather was growing warm, but on reaching their destination found that spring had not yet arrived, the country being still bleak and desolate. Most of them were poorly clad and without funds. Consequently, many suffered from want and disease and consequently became public charges. As soon as it was convenient for them, however, large numbers returned to their homes where they scattered such discouraging reports that others who had planned to move declined to do so. Nevertheless, about a third of them remained in Kansas and of this portion a fairly large number attained a creditable degree of prosperity.

The years of the later eighties and the early nineties also witnessed a few small interstate movements of Negroes.448 For a long time it was the custom of employers in the mineral districts of the Appalachian Mountains to hire only foreign labor to do their work, but during the time just referred to this labor failed to satisfy the demand. In order to meet this emergency the employers at once dispatched their agents to different parts of the South to appeal to the Negroes for their labor. The efforts of these agents were not without effect, because many Negroes soon flocked to the mining districts of Birmingham, Alabama, to those of East Tennessee, and to those of West Virginia. Also, large numbers went to southern Ohio, where they were employed in the places of white laborers, who were on a strike, demanding higher wages.

As is evident in the preceding citations, the Negroes of the South are inclined not only to move to the North and West, but are also prone to move about freely within the South. This can be further substantiated by a brief study of the interdivisional movements of the Negro population of the South. In 1910, according to the Federal Census, it was found that 1.4 per cent of the Negroes living in the South Atlantic Division, 5.8 per cent of those residing in the East South Central Division, and 13.1 per cent of those in the West South Central Division, were born in places outside these respective sections. On the other hand, it was shown that the South Atlantic Division registered a loss of 392,927 from its Negro population, the East South Central a loss of 200,876, whereas the West South Central Division revealed a net gain of 194,658 in its Negro population. Thus, while two divisions lost, the third gained heavily by interdivisional Negro migration.449 This tendency toward interdivisional migration on the part of Negroes is, however, exhibited in a less degree than is the case on the part of whites. In 1910, 16.6 per cent of the Negroes had moved to other States than those in which they were born, whereas 22.4 per cent of the whites were found in States other than those in which they were born.450

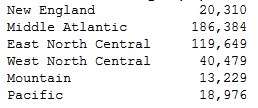

Likewise, the Negroes are inclined to move about freely from section to section within the bounds of the North and West. In 1910, 47 per cent of the Negroes living in the New England Division, 52.3 per cent of those in the Middle Atlantic Division, 50.4 per cent of those in the East North Central Division, 32.1 per cent of those in the West North Central Division, and 80 per cent of those living in the Mountain Division and 77.7 per cent of those living in the Pacific Division, were born, in each case, in places outside of these sections.451 Each section showed also a loss of a certain per cent of its total native Negro population through migration to some other division. In this respect, New England showed a loss of 18.5 per cent, the Middle Atlantic States a loss of 10.5 per cent, the East North Central 16.2 per cent, the West North Central 18.2 per cent, the Mountain 43.9 per cent, and the Pacific 26.4 per cent.452 While this was the case, each division, nevertheless, received in turn, through migration from other places, enough newcomers to show a decided gain in its total Negro population. These gains in numbers were as follows:453

While much of the Negro migration has been interdivisional movements within the three major sections of this country, yet a very considerable amount of it has been directed from the South to the North and West. Between 1870 and 1910, a period of forty years, there was a marked increase in the number of Negroes who were born in the South but who had migrated to the North. In 1870 the number was 149,000, but in 1910 it had increased to 440,534.454 This latter estimate is undoubtedly much less than the actual number of migrants, for it does not account for those who might have died or returned to the South or elsewhere before the taking of the Federal Census. Moreover, it is a fact that since the Civil War the Negro population of the North has been increasing faster than that of the South. In 1860 there were 344,719 Negroes in the North; in 1910 there were 1,078,336, an increase of 212.8 per cent for the fifty years' period. In 1920 there were 1,472,448 Negroes in the North, an increase of 43.8 per cent in ten years. In the West there were 78,591 in 1920. In the South, on the other hand, during the period from 1870 to 1910, the rate of increase was only 111.1 per cent. From 1910 to 1920 there was an increase of only 1.9 per cent whereas there was between 1900 and 1915 an increase of 10.4 per cent in that section in the Negro population in the South. During the past fifty years, therefore, the relative increase of Negroes in the North has been more than double that of the Negro population in the South. Before 1860 every census, except that of 1840, showed a greater relative increase in the Negro population of the South than in that of the North. Since that time, however, this condition has been reversed.455 This increase of the Negro population in the North is undoubtedly due to migration from the South, and not to natural increase, because the vital statistics of Northern communities show that the Negro birth-rate is barely sufficient to balance the death-rate.456

Not only have Negroes been moving from the South to the North and West, but they have also been migrating from these latter sections to the South. Immediately after the Civil War a small number of Negroes left the North and made their way to the South.457 This movement was composed of intelligent Negroes who had been fortunate enough to enjoy some of the educational opportunities of the North and who, because of this equipment, felt that they might be of service to the race during the Reconstruction period in the South. They were the ones who became the antagonists of the Carpet-baggers—the arch-corrupters of the governments of the Southern States. There were, however, other reasons why these men went South. In the first place, some had found northern communities so hostile to them that their progress was impeded; in the next place, many desired to reunite with their relatives from whom they had been separated by their flight from slavery; finally, others moved in response to a spirit of adventure to enter a new field which offered opportunities of all sorts.

The Federal Census of 1910, moreover, furnishes evidence of Negro movement from the North and West to the South.458 This report shows that during that decade 41,489 Negroes who were born in the North and West were living in the South. This migration from these former sections to the South, though less considerable in volume than the migration from the South, is, nevertheless, proportionately greater when considered in relation to the Negro population born in these two sections than the migration from the South when the latter movement is, likewise, considered in its relation to the total Negro population born in the South. Thus the 41,489 Negroes born in the North and West but living in the South in 1910 constituted 6.5 per cent of the total Negro population born in the North and West, whereas the 440,534 Negroes born in the South but residing in the North formed only 4.8 per cent of the total Negro population born in the South.

The fact that this recent Negro migration, as has been stated, was a movement to the large cities and industrial centers of the North and West should give no occasion for surprise, because this has been in progress for more than three decades. During this period the Negroes have shown a decided tendency to flock to the large cities of the North and West, and also to those of the South. This is verified by the discovery that since 1880 nine cities of the North and West have shown considerable increase in their Negro population. These attractive cities thus popularized are as follows: Boston, Greater New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Cincinnati, Evansville, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. The increase for these nine cities between 1880 and 1890 was about 36.2 per cent; between 1890 and 1900 it was about 74.4 per cent; from 1900 to 1910 about 37.4 per cent; and from 1910 to 1920 about 50 per cent. In the first decade the increase was more than three times the increase of the total Negro population; in the second it was more than four times as large; in the third the increase was nearly three times larger; and in the fourth nearly five times as large as the increase of the same population. Likewise, during the same period there was a great Negro influx to the larger cities of the South, but the rate of increase was less than that of the Northern cities. In fifteen Southern cities the percentage of increase was about 38.7 per cent during the first decade; during the second about 20.6 per cent; and from 1900 to 1916 the increase (based on figures for sixteen cities) was about the same as that of the preceding decades.459

These numerous instances of previous Negro movements show that the recent migration is no new and strange phenomenon, that Negroes, like other elements of the population of the United States, have shown a tendency since their emancipation to move from place to place. This recent exodus was simply a part of a long series of movements which have been in progress for more than half a century. It is, therefore, much like the others and differs from them only in its immense volume. In the course of this migration, as we observed, the number of Negroes who moved to the North and West was probably a half million—a number which perhaps exceeds or certainly equals that which resulted from all other movements from the South to the North during a period of forty years. Herein alone, if such a view of it can be held at all, lies its strangeness and remarkability as a social phenomenon.

Chapter III

SOURCE, VOLUME, DESTINATION, AND COMPOSITION

The exodus of the Negroes during the years from 1916 to 1918 occurred with such suddenness and attained such an immense volume that for a time it appeared to many observers that the whole "Black Belt" was shifting itself northward. Inasmuch as at the very time this migration reached its zenith this country had just entered into a state of war with Germany, it attracted almost nation-wide attention, and from some quarters the fear was that it would have the effect, either directly or indirectly, of obstructing the National Government in its prosecution of the war. Numerous also were the apprehensions of the economic, political, and social problems that might follow in the wake of this movement. On almost every hand, therefore, the discussions concerning this migration became legion, and varying were the opinions expressed regarding its causes and its probable effects upon the sections of the country involved and upon the migrants themselves.

It is uncertain as to the exact time when this movement began, because it was going on some time before any notice was taken of it. It is known, however, that conditions favorable to its beginning were manifest shortly after the outbreak of the European War, when, on account of this catastrophe, immigration practically ceased and thousands of alien laborers departed for their native lands. This caused a serious labor shortage in the Northern industries, and in order to obviate this employers, during the spring of 1915, sent agents into the South to seek Negro laborers. If, as a result of the efforts of these agents, Negroes were induced to go North, then the number of those who moved was so small and in such scattered instances as to make it unworthy of being called a migration. This view is taken because it was not until nearly a year afterward that Negroes began to move in numbers sufficiently large to attract public notice.

The Negro migration in its truest sense, therefore, had its beginning in 1916 and was precipitated as follows: "A national philanthropic organization arranged with some Northern tobacco growers to import Negro students from some of the Southern private institutions for summer work and early in May, 1916, brought the first two trainloads from Georgia. Then the agent of a large Northern railroad, taking advantage of the publicity given this venture, used the name of this organization to get migrants to come North."460 Other railroads and steel mills were also in great need for laborers and thus sent their agents in the South to solicit labor. These agents moved about through the States of the South and offered at first free transportation to the prospective laborers and pictured to them in very glowing terms the high wages and advantages of the North. This they did not have to do very long, "for the news spread like wild-fire. It was like the gold fever in '49. Negroes sold their simple belongings and in some instances valuable land and property and flocked to the Northern cities, even though they had no objective work in sight."461 Regarding this same point, Mr. Ray Stannard Baker holds that during the spring of 1916 "trains were backed into Southern cities and hundreds of Negroes were gathered up in a day, loaded into the cars and whirled away to the North. Instances are given showing that Negro teamsters left their horses standing in the streets or deserted their jobs and went to the trains without notifying their employers or even going home."462

The next question which seems in order is whence came these migrants. As far as is known up to now they came largely from thirteen of the Southern States and from those lying mainly east of the Mississippi River. These States are as follows: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia—the cotton, tobacco, and sugar cane regions of the South.463 Of these the States which paid the heaviest toll in the number of migrants are Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Tennessee. In this respect Mississippi stands first, Alabama second, and Georgia third.464