полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 6, 1921

Further evidence of the economic improvement of free Negroes during this period is evidenced by a significant appeal made by the members of the American Convention of Abolition Societies to the Free Negroes of New York in 1805. "The education of your offspring," said these friends of the Negroes, "is a subject of lasting importance and has obtained a large portion of your attention and care. In this, too, we call upon you for your aid; many of you have been favored to acquire a comfortable portion of property and are consequently enabled to contribute in some measure to the means of educating your offspring."297 In response to this appeal, the society of free people of color was established in 1812 to maintain a Free Orphan School in New York City and employed two teachers; and there were three other schools which they supported with their tuition fees, while those who were not sufficiently well circumstanced to educate their children sent them to the African Free Schools maintained by the New York Manumission Society.298

These African Free Schools were conducted in such a way as to have a direct bearing on the economic improvement of the Negroes. In 1818 the New York Mission Society informed the American Convention of Abolition Societies that the former had devised a plan of extending their care to certain children of color who had completed their course of instruction in the New York African Free Schools "in putting them at some useful trade or employment." These friends of the race in New York said that it had long been a regret that Negro children "educated at their schools had been suffered after leaving it to waste their time in idleness, thereby incurring those vicious habits which were calculated to render their previous education worse than useless." To remedy this evil they appointed an Indenturing Committee, whose duty was to provide places for these children and put them at a trade or some other employment when they had completed their education. The Committee took special care that the persons with whom children might be placed should be those of good character and while on the one hand they insisted that the children demean themselves with sobriety they extended their guardian care to them so that they might not "become subjects of oppression and tyranny." This Indenturing Committee in reaching its decision as to the sort of occupations to which the children could be apprenticed expressed a decided preference for agricultural pursuits, being persuaded that an occupation of this nature was far more conducive to the moral improvement of these Negroes than the pursuits of the city under the most favorable circumstances. This plan upon being presented to the parents and guardians of these children was favorably received, but it does not appear that a large number of them thereafter participated in agriculture.299

The activity of the girls who had received instruction in household economics in free schools showed progress in another direction. They formed a society under the name of the African Dorcas Association for the purpose of procuring and making garments for the destitute. The boys, too, contributed their share to this progress, taking up such trades as sail makers, tire-workers, tailors, carpenters and blacksmiths.

Such reports300 represent the condition of the free Negroes of New York before slavery was completely abolished. This change in the status of the Negroes then, and the evolving industrial system effected a change in the economic condition of the Negro throughout the city.301

It must be remembered in this connection, however, that these Negroes experienced difficulties on account of their color either in obtaining a thorough knowledge of the trades or, after they had obtained it, in finding employment in the best shops. White and black laborers at first worked together in the same room and at the same machine. But soon prejudice developed. It was made more intense by the immigration into this country of a large number of poor Germans and Irish, who came to our shores because of the disturbed conditions of Europe. Their superior training and experience enabled them to get positions in most of the trades. Most northern men, moreover, still objected to granting Negroes economic equality. When the supply of labor exceeded the demand, the free Negroes, unable to compete with these foreigners, were driven not only from the respectable positions, but also from the menial pursuits. Measures to restrict to the whites employment in higher pursuits were proposed and where they were not actually made laws, public opinion, to that effect, accomplished practically the same result. This reversal of the position of labor, however, did not take place without a struggle, for there soon arose ill-feeling which culminated in the riots between 1830 and 1840.302

In spite of this condition, Arthur Tappan, Gerrit Smith and William Lloyd Garrison reported to the Second American Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Color that "by perseverance, the youth of color could succeed in procuring profitable situations.303 To these benefactors, however, it was soon evident that Negroes had to be trained for the competition with white laborers or be doomed to follow menial employment. In accordance with this Gerrit Smith established in 1834 a school in Peterboro, for the purpose of training Negro youths under the manual labor system.304 With such training, he believed, free Negroes would gain a livelihood, send their children to school, and gradually accumulate money. He hoped that many of them would make progress to the extent of possessing property valued at $250, which amount would enable citizens of color305 to vote in the State of New York.

Hoping to put an end to economic poverty among these Negroes, Gerrit Smith devised a scheme for the distribution of 3,000 parcels of land of 40 or 60 acres each among the unfortunate blacks then handicapped in this untoward situation in New York City. From a list of names furnished him by Rev. Charles B. Ray, Rev. Theodore F. Wright and Dr. J. McCune Smith, three prominent Negroes in New York City, Gerrit Smith apportioned this land among the Negro colonists in the counties of Franklin, Essex, Hamilton, Fulton, Oneida, Delaware, Madison, and Ulster. On account of the intractability of the soil, however, the harshness of the climate, and, in a great measure, the inefficiency of the settlers, the enterprise was a failure and offered no relief to the economic condition of the Negroes in this city.

It will be interesting to note the observations of a promoter of colonization on the condition of Negroes in New York City at this time. While his statements must be taken with some reservation they, nevertheless, contain a truth which must be taken into account. Hoping to induce Negroes to accept colonization in Africa, he endeavored to show that they could not finally succeed in the struggle in competition with the white laborers and would be crowded out of the higher pursuits of labor. He referred to the fact that a few years prior to 1846 there was a vast body of colored laborers in New York but that at that time they could not be seen. The writer inquired as to "who may find a dray or a cart or a hack driven by a colored man?" "Where are the vast majority of colored people in the city?" "None," said he, "can deny that they are sunken much lower than they were a few years ago and are compelled to pursue none but the meanest avocations."

The gentleman making these observations tried to emphasize this striking contrast by calling attention to the fact that New York was a place that had a great deal of compassion for the slave while it was neglecting to take into account the awful condition of the free Negroes, in spite of the fact that the process of their depression had been going on at the same time that the abolitionists in New York were working for the emancipation of the slave. Although these friends of the Negroes and the Negroes themselves had during these years been boldly asserting their rights and demanding to be elevated, they had been losing ground, sinking into meaner occupations and less lucrative employments. He believed that the day was not far when every desirable business in the city would be entirely monopolized by the whites because of the rapid influx of foreigners who had to labor or serve and knew how to toil to advantage, to the extent that they could make their labor more valuable than that of the people of color.306

In things economic, however, the free Negroes of New York made considerable improvement after 1845; a decided improvement in this respect was noted by 1851. So evident was this progress that the colonizationists who had repeatedly referred to the poverty of the Negroes and the prejudice against them in the laboring world as a reason why they should migrate to Africa, thereafter ceased to say very much about their poverty, shifting their complaint rather to social proscription. In 1851 a contributor to The African Repository, the organ of the American Colonization Society, discussed the situation of the 48,000 free Negroes of New York. Directing his attention to the 14,000 living in the metropolis, the editor said that the condition of 4,000 of them approached that of comfort; 1,000 of the number having substantial wealth, or that one out of every ten was in a pleasant and enviable social condition. As this pessimist was compelled to concede that this was not a bad showing for an oppressed people he goes off on another line, saying: "Everywhere the Negro, whatever his wealth or education or talents, is excluded from social equality and social freedom."307

There were many instances of individual enterprise, however, but these often meant little since Negroes had such a little knowledge of business that white persons often defrauded them out of what they accumulated. Sojourner Truth accumulated more than enough money to supply her wants, but lost some of it by depositing it in a bank without taking account of the sum which she deposited and without asking for the interest when she drew her money from the bank.308 One Pierson persuaded her to take her money out of the bank and invest it in a common fund which he was raising to be drawn upon by all needy and faithful free Negroes.309 Her savings, therefore, served to increase this fund, which instead of relieving the economic condition of many needy free Negroes enriched this white impostor.

As evidences of this unusual progress of the Negroes there are many instances of persons who gained wealth in spite of the various handicaps. Many of the caterers and restaurant keepers of high order of New York were Negroes, the most popular of whom being Thomas Downing, the keeper of a restaurant under what is now the Drexel Building, near the corner of Wall and Broad streets, New York City.310 Abner H. Frances and James Garrett, were formerly extensive clothiers of Buffalo, New York, doing business to the amount of $60,000 annually. They continued their enterprise successfully for years, their credit being good for any amount of money they needed. They failed in business in 1849 but thereafter adjusted the claims against them.311 Henry Scott and Company, of New York City, engaged in the pickling business, principally confined to supplying vessels.312 Edward V. Clark, another business man of New York, had a jewelry establishment requiring much capital. His name had, moreover, a respectable standing even among the dealers of Wall Street.313 Mr. Huston kept for years an intelligence office in New York. He was succeeded by Philip A. Bell, an excellent business man. Concerning it, Austin Steward reported in his book entitled "The Condition of the Colored People" that "his business is very extensive, being sought from all points of the city by the first people of the community.314

Many other names may be mentioned. William H. Topp was one of the leading merchant tailors of Albany, New York. Starting in the world without aid he educated and qualified himself for business.315 In Penyan, Messrs. William Platt and Joseph C. Cassey were said to be carrying on an extensive trade in lumber.316

Situated in the midst of a rapidly developing country the enterprises of these free Negroes increased in importance every year. This was especially true of the drug stores of Dr. James McCune Smith, on Broadway, a Negro physician, who was practicing in New York City during the thirties, and of the establishment of Dr. Philip White, on Frankfort street. Many Negroes accumulated considerable wealth. Edward Bidwell successfully operated during the period of 1827-40 two stores on the main street of New York City, hoarding considerable money. Austin Steward, still another instance of New York City, made "handsome profits" from the sale of spirituous liquors. At one time he said that no further exertion was necessary on his part to enjoy life, or to better his economic condition. Finally, William Smith, a shrewd sailor of New York, managed to accumulate considerable wealth.

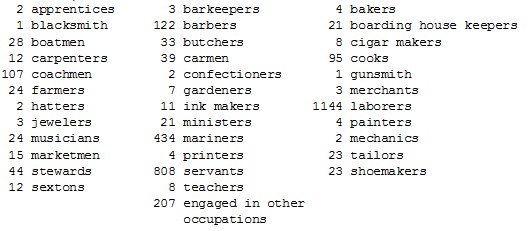

The statistics of the census of 1850 give further evidences of this general progress. Of the 50,000 free people of color in the State of New York over 15 years of age in 1850, sixty were clerks, doctors and lawyers and about 55 were merchants and teachers.317 There were, moreover:

Many Negroes used wisely the money which they obtained from these businesses. Out of a free population of 50,000 Negroes, 5,447, or about one in ten was in school during this period. In a pamphlet entitled the Present Condition of Free People of Color published by James Freeman Clarke in 1859, the author stated that they were no less neat in person and attire than their white neighbors.318 One year during the period from 1850 to 1860 Negroes of New York City invested in business carried on by themselves $775,000; in businesses of Brooklyn $76,000. That same year these free Negroes purchased real estate in New York worth $733,000, and in Brooklyn $276,000.319

With complete freedom in New York, free Negroes made more efforts to improve their condition. There were established several newspapers which served not only to present their cause to the public but also as economic factors. First of these must be mentioned a publication called Freedom's Journal or The Rights of All. This paper, edited by James B. Russworm, the first Negro college graduate in the United States, and Rev. Samuel F. Cornish, was established in March, 1827.320 Another journal, styled The Weekly Advocate, changing its name later to The Colored American, appeared in New York, March 4, 1837. The editor was Philip A. Bell. Later Charles Bennett Ray became one of the proprietors and editors. Finally, mention must be made of such journals of this period as The Elevator, of Albany, edited by Stephen Myers; The Genius of Freedom, by David Ruggles; People's Press, by Thomas Hamilton; and North Star, by Frederick Douglass. Concerning the last named publication, it was generally said that it was conducted on a higher plane than any of the others and that it was among the first newspapers of the country.

Arnett G. Lindsay.DOCUMENTS

THE APPEAL OF THE AMERICAN CONVENTION OF ABOLITION SOCIETIES

The student of the so-called Negro problem of today may find it profitable to study the methods of persons thus concerned more than a century ago. What their plans were, what machinery they constructed for carrying them out, and the hopes they had for ultimate success, will furnish much material for reflection for social workers. There is published below, therefore, a number of the annual appeals of the American Convention of Abolition Societies to the various branches, setting forth the annual review of the work, the general survey of results obtained and the ways and means to carry it forward to a successful completion.

To the Antislavery GroupsTo the

Society forpromoting the abolition of Slavery, EcIt is with peculiar pleasure we inform you, that the Convention of Delegates, from most of the Abolition Societies formed in the United States, met in this city, have, with much unanimity, gone through the business which came before them. The advantages to be derived from this meeting are so evident, that we have agreed earnestly to recommend to you, that a similar meeting be annually convened, until the great object of our association—the liberty of our fellowmen—shall be fully and equivocally established.

To obtain this important end, we conceive that it is proper, constantly to have in view the necessity of using our utmost and unremitting endeavors to abolish slavery, and to protect and meliorate the condition of the enslaved, and of the emancipated. The irresistible, though silent progress of the principles of true philosophy, will do much for us; but, placed in a situation well adapted to promote these principles, it surely becomes us to improve every occasion of forwarding the great designs of our institutions. For this purpose, we think it proper to request you to unite with us, in the most strenuous exertions, to effect a compliance with the laws in favour of emancipation; and, where these laws are deficient, respectful applications to the State-Legislatures should not be discontinued, however unsuccessful they may prove.—Let us remember, for our consolation and encouragement in these cases, that, although interest and prejudice may oppose, yet the fundamental principles of our government, as well as the progressive and rapid influence of reason and religion, are in our favour—and let us never be discouraged by a fear of the event, from performing any task of duty, when clearly pointed out; for it is an undoubted truth—that no good effort can ever be entirely lost.

While contemplating the great principles of our associations, we cannot refrain from recommending to your attention the propriety of using your endeavours to form, as circumstances may require, Abolition Societies in your own, and in the neighboring States; as, for want of the concurrence of others, the good intentions and efforts of many an honest and zealous individual are often defeated.

But, while we wish to draw your attention to these objects, there is another which we cannot pass over. We are all too much accustomed to the reproaches of the enemies of our cause, on the subject of the ignorance and crimes of the Blacks, not to wish that they were ill-founded. And though, to us, it is sufficiently apparent that this ignorance, and these crimes, are owing to the degrading state of slavery; yet, may we not, with confidence, attempt to do away the reproach?—Let us use our endeavours to have the children of the emancipated, and even of the enslaved Africans, instructed in common literature—in the principles of virtue and religion, and in those mechanic arts which will keep them most constantly employed, and, of course, will less subject them to idleness and debauchery; and thus prepare them for becoming good citizens of the United States: a privilege and elevation to which we look forward with pleasure, and which we believe can be best merited by habits of industry and virtue.

We shall transmit you an exact copy of our proceedings, with the different memorials and addresses which to us have appeared necessary at this time; and would recommend to you the propriety of giving full powers to the Delegates who are to meet in the year 1795; believing that the business of that Convention will be rendered more easy and more extensively useful, if you send, by your Representatives, certified copies of the constitution and laws of your Society, and of all the laws existing in your state concerning slavery, with such facts relative to this business, as may ascertain the respective situation of slavery, and of the Blacks in general.

To the

Society forpromoting the abolition of Slavery, &cThe Delegates, from the several Abolition Societies in the United States, convened in this city, express to you, with great satisfaction, the pleasure they have experienced from the punctual attendance of the persons, delegated to this Convention, and that harmony with which they have deliberated on the several matters that have been presented to them, at this time, for their consideration. The benefits which may flow from a continuance of this general meeting, by aiding the principal design of its institution—the universal emancipation of the wretched Africans who are yet in bondage, appear to us so many and important, that we are induced to recommend to you, to send Delegates to a similar Convention, which we propose to be holden, in this city, on the first day of January, in the year one thousand, seven hundred and ninety-six.

We have thought it proper to request your further attention to that part of the address of the former Convention, which relates to the procurement of certified copies of the laws of your state respecting slavery; and that you would send, to the next Convention, exact copies of all such laws as are now in force, and of such as have been repealed. Convinced that an historical review of the various acts and provisions of the Legislatures of the several states, relating to slavery, from the periods of their respective settlements to the present time, by tracing the progress of the system to African slavery in this country, and its successive change in the different governments of the Union, would throw much light on the objects of our enquiry and attention, and enable us to determine, how far the cause of justice and humanity has advanced among us, and how soon we may reasonably expect to see it triumphant;—we recommend to you, to take such measures as you may think conducive to that purpose, for procuring materials for the work now proposed, and assisting its publication; and to communicate, to the ensuing Convention, what progress you shall have made toward perfecting the plan here offered for your consideration and care.

Believing that an acquaintance with the names of the officers of the several Abolition Societies, would facilitate that friendly correspondence which ought always to be preserved between our various associations, we request that you would send, to the next, and to every future Convention, an accurate list of all the officers of your Society, for the time being, with the number of members of which it consists. And it would assist that Convention in ascertaining the existing state of slavery in the United States, if you were to forward to them an exact account of the persons who have been liberated by the agency of your Society, and of those who may be considered as signal instances of the relief that you have afforded; and, also, a statement of the number of free blacks in your state, their property, employments, and moral conduct.

As a knowledge of what has been done, and of that success which has attended the efforts of humanity, will cherish the hope of benevolence, and stimulate to further exertion, we trust that you will be of opinion with us, that it would be highly useful to procure correct reports of all such trials, and decisions of courts of judicature, respecting slavery, a knowledge of which may be subservient to the cause of abolition, and to transmit them to the next, or to any future Convention.

It cannot have escaped your observation, how many persons there are who continue the hateful practice of enslaving their fellow men, and who acquiesce in the sophistry of the advocates of that practice, merely from want of reflection, and from an habitual attention to their own immediate interest. If to such were often applied the force of reason, and the persuasion of eloquence, they might be awakened to a sense of their injustice, and be startled with horror at the enormity of their conduct. To produce so desirable a change in sentiment, as well as practice, we recommend to you the instituting of annual, or other periodical, discourses, or orations, to be delivered in public, on the subject of slavery, and means of its abolition.

We cannot forbear expressing to you our earnest desire, that you will continue, without ceasing, to endeavour, by every method in your power which can promise any success, to procure, either an absolute repeal of all the laws in your state, which countenance slavery, or such an amelioration of them as will gradually produce an entire abolition. Yet, even should that greater end be happily attained, it cannot put a period to the necessity of further labor. The education of the emancipated, the noblest and most arduous task which we have to perform, will require all our wisdom and virtue, and the constant exercise of the greatest skill and discretion. When we have broken his chains, and restored the African to the enjoyment of his rights, the great work of justice and benevolence is not accomplished—The new born citizen must receive that instruction, and those powerful impressions of moral and religious truth, which will render him capable and desirous of fulfilling the various duties he owes to himself and to his country. By educating some in the higher branches of science, and all in the useful parts of learning, and in the precepts of religion and morality, we shall not only do away with the reproach and calumny so unjustly lavished upon us, but confound the enemies of truth, by evincing that the unhappy sons of Africa, in spite of the degrading influence of slavery, are in no wise inferior to the more fortunate inhabitants of Europe and America.