Полная версия

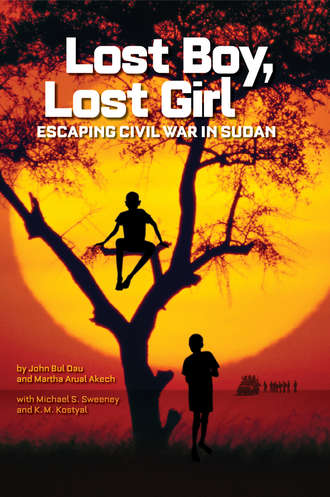

Lost Boy, Lost Girl: Escaping Civil War in Sudan

Lost Boy, Lost Girl

ESCAPING CIVIL WAR IN SUDAN

By John Bul Dau and Martha Arual Akech

With Michael S. Sweeney and K. M. Kostyal

To our lovely Children; Agot, Leek, and our three-day-old daughter, Akur. This book is dedicated to you. When you are able to read on your own, it should act as an introduction to the ordeals that your mother and I went through. You are sweet kids, and we thank Almighty God for keeping us alive during the war, a time when we never thought we would survive to even have children! —j&m

To all of the other lost children in the world, whose stories have not been told —kmk

To the spirit of Sudan —ms

Table of Contents

Part One PEACE

Part Two WAR

Part Three REFUGE

Part Four WAR

Part Five REFUGE

Part Six PEACE

Afterword

Timeline

Photographic Insert

John

When I was a young boy, my great-uncle Aleer-Manguak was killed while trying to protect our cattle from a lion. His bravery made me proud.

My people, the Dinka, raise cows in Southern Sudan. We like to drink their milk, and we use them as a form of money. Protecting our precious cows from predators is a constant problem. Sometimes we must kill or be killed.

One day five lions sneaked into the pastures near Paguith, my first village. Lions are smart and work in groups. If they want to attack a herd, they first try to make the cows panic. They sometimes do this by creeping near the cattle and spreading their urine on the ground. Then they quietly move to the opposite side of the herd. When the cows wander far enough to sniff the odor of lion urine, they know a killer is nearby and run in the opposite direction—right toward the waiting lions. This is exactly what happened that day. Hundreds of cows ran into the trap, and two fell to the lions’ fangs and claws. My brother and some other Dinka boys saw what happened and tried to chase the lions away. They ran at the lions and threw sticks to drive them from their kill. That just made the lions angry. Some of them turned on the boys, and they had to run for their lives.

The boys hurried to the village and alerted everyone that lions had attacked the cattle. The women of the village began to shout, and the men began to arm themselves. My father and great-uncle got their knives and spears and left their houses to meet the other men of the village. They quickly decided to form a hunting party. They would have gone after the lions right then, but night had begun to fall and they had to suspend their pursuit. Everyone went to bed anxious for the hunt to begin. After the sun rose the next morning, a hunting party that had special skills in tracking lions began to follow their path. About thirty men, all armed with spears, set off after the trackers through the tall grass.

By the time they found the lions, two had run off, but three remained in the thick grass and brush. The hunters circled them and began to walk toward each other, drawing the circle smaller and smaller. Two of the three lions didn’t want anything to do with the Dinka hunters and escaped through gaps in the circle. That left one. He was a big male with a broad face and a golden mane.

Remember how I said lions are smart? This one certainly was. He did not want to tangle with humans and was trying to keep his distance, but the shrinking circle gave him no chance to flee. The lion began to get nervous. To get close enough to actually kill the lion, the hunters needed to create a distraction. The Dinka say, “Who is going to bring the lion?” It is a special kind of job. The bringer stabs the lion to make it angry. The lion then chases its attacker, who runs for his life. The fastest runners in the village train to “bring the lion.” My great-uncle was one of them.

As the men of my village knelt with their spears pointed at the center of the circle, Aleer-Manguak and another runner rushed straight at the lion. As they sped by, they stabbed the great beast with the tips of their spears. The lion roared in anger and pain. It rose on all four legs and chased Aleer-Manguak. The beast caught him just as he reached the circle of hunters. It swiped at him with one paw, tearing open his shoulder and breaking his ribs. The other hunters swarmed over the lion and pierced its flesh with their spears, killing it quickly. My great-uncle lived just a little while longer, and then he died too.

The entire village honored my great-uncle. The hunters took the lion’s body and cut off the tail, paws, and mane. They gave these to Aleer-Manguak’s family as tokens of respect for his brave deed and his self-sacrifice. The family hung the prizes in their luak, a round Dinka cattle pen with a thatched roof.

Even as a boy of seven or eight, I knew why everyone honored Aleer-Manguak in death. Almost from birth, a child is taught the values of the Dinka, which my great-uncle had in abundance. These values include respect, courage, hard work, and self-sacrifice. A Dinka child is also taught to fight for family, village, tribe, and country. The strongest fighters are those who keep two rules. First, they never, ever give up, no matter what the odds are against them. And second, like the lions, they work together. A Dinka man who follows these rules and maintains the values he learned as a boy can grow up to be a great leader, like my great-uncle. At the time I had no idea how much I would have to live by these rules just to survive the ordeals of my life. Aside from the occasional marauding visit by a lion or hyena, my childhood years were peaceful and fun.

Nobody kept exact records in Southern Sudan, but my family believes that I was born in July 1974. My father was Deng Leek Deng Aleer. He had been a mighty wrestler when he was young and later became a judge. He did not go to school to learn the law. Instead, we Dinka say that he held the laws in his heart. He knew our traditions and our values and was called upon to settle disputes. He disciplined me severely when I was young, especially if I showed any disrespect. At the time I thought he was too strict, but now I realize that he was raising me to be strong, as a Dinka man should be.

My mother was Anon Manyok Duot Lual. She was the daughter of a Dinka chief and was considered quite an excellent bride. My father had to pay many cows to her male relatives as a sign of his respect before he could marry her and give their children his name. It is common among the Dinka for a man to have more than one wife. After my father married my mother, he took three more wives, and he had many children. I am the youngest son of my mother.

Like all good Dinka, my family raised cattle. These are not the cows you see on North American farms. Dinka cows look wilder than their American cousins and have thick horns that are two to three feet long. Their milk is sweet, and we drink it all the time. We slaughter a cow for its meat only to mark a big occasion. We believe that cows are a gift from God.

Our legends say that God offered the first Dinka man a choice between the gift of the first cow and a secret gift, called the “What.” God told the first man to carefully consider his choice. The secret gift was very great, God said, but he would not reveal anything more about it. The first man looked at the cow and thought it was a very good gift. “If you insist on having the cow, then I advise you to taste her milk before you decide,” God said. The first man tried the milk and liked it. He considered the choice and picked the cow. He never saw the secret gift. God gave that gift to others.

The Dinka believe that the secret gift went to the people of the West. It helped them invent and explore and build and become strong. Meanwhile, the Dinka never built factories or highways or cars or planes. They were content to be farmers and cattle raisers. They lived happily for centuries, drinking milk and using cows as currency. Cows remain the lifeblood of the Dinka culture.

Narrow dirt paths link one village with another all over Southern Sudan. There are no paved roads and virtually no buildings of metal or brick. Mud, sticks, leaves, and grass are our construction materials. There are no phones, no computers, no cars, no kitchen appliances—virtually none of the conveniences that many people in the world take for granted. Our culture has not changed much in hundreds of years, and we like it that way.

Southern Sudan is very flat. The land is covered with grass that grows eight feet high between patches of forest and farmland. The year follows seasons of rain and drought. When it rains, the flat lands fill with standing water and our villages become like swamps. When the rains stop, the land dries to dust and the sun burns very, very hot. Some lands—in an area called the Sudd that separates Northern and Southern Sudan—never go dry. Even late in the dry season, these lands hold enough water to grow grasses to feed our cattle. Beyond those swampy lands is the White Nile River. It has crocodiles, mosquitoes, and hippopotamuses. For many centuries, the swamp and the dangerous animals that live in it served as a barrier to people who wanted to explore Southern Sudan. That’s why the Dinka lived in isolation until the nineteenth century, when British explorers and missionaries began pushing through the swamp.

My father’s father’s brother was a great man. His name was Deng Malual Aleer. He was a big chief in Southern Sudan and fought on the side of the British colonizers against the Arabs who lived in Northern Sudan and wanted to control the whole country. He gave permission for missionaries to do their work in the southernmost part of Sudan, and that is how my family became Christians. Because of Dinka traditions and the work of the missionaries, I have two names. My traditional Dinka name is Dhieu-Deng Leek (pronounced “Lake”). I also am known by my Christian name, John Bul Dau. Many Dinka families give their children a name from the Bible when they are baptized, and that is how I became John at age four or five.

Like all Dinka children, I had to do chores from a very early age. I got up when the red circle of the sun cleared the horizon. Every morning, I went immediately to our luak with my brothers to lead our cows outside. When the luak was empty, we cleaned the floor. We gathered up the dung from the night before and hauled it outside. Then we broke it into tiny bits to dry in the sun. We burned the dried dung every day. It gave off a smelly smoke that protected our cows from biting flies and other pests.

Meanwhile, my father and mother tended to their garden, cutting weeds from their patches of corn, beans, sorghum, and pumpkins. Mother took a break around midday to make a lunch of thin griddle cakes. The older boys kept watch over the cattle, while my friends and I played with our toys. We did not have fancy playthings that make noise when you push a button. We made toy cows out of clay and made the sounds of cows and goats with our mouths. We had fun pretending to run our own farms. We also played a running game called alueth. It’s played with two bases, one for someone taking the role of a lion and the other for children whom the lion “hunts.” The children leave one base and run toward the safety of the other. If the lion catches a child between the bases, he joins the lion’s team. As more and more children become “lions,” it gets harder and harder for the remaining children to avoid getting captured.

Once I was old enough, I went with the older boys to protect the cattle as they grazed on the thick grasses around our village. Like the other boys, I learned how to fight with knives and spears and clubs. I wrestled with my friends until I grew strong and tall. My friends and I prided ourselves on learning how to throw one another to the ground and on mastering the many moves of a champion wrestler.

I didn’t go to school. The only schools were in the biggest of villages, far away, or in the northern part of Sudan, where people spoke Arabic. Instead, I learned what I needed to know through the rituals of storytelling. Everyone played games with riddles, shared stories among the family after dinner at the end of the day, and told stories at cattle camp, a grassy place away from home where villagers tended their precious cows. Our stories and riddles not only taught us about the animals and plants and people of our world, but they also bathed us in lessons of right and wrong. When we heard stories about hyena, for example, we learned how his greedy, self-centered ways caused him many problems. We learned that we wanted to be more like the noble eagle, the smart fox, and the powerful elephant.

Every night my brothers and sisters and I told each other tales we had heard during the day, and we begged our parents to share with us the older stories from when people and animals lived together and spoke to one another. Then my mother checked to be sure the doors and windows had been sealed against the clouds of mosquitoes outside, and we lay on our beds of cowhide. Our village had no electricity, and our daytime cooking fires burned too low at night to give off any light, so each night brought nearly total darkness to the inside of our house and luak. Night after night I drifted off to sleep, never dreaming how soon our beautiful storytelling evenings would end.

Martha

I didn’t grow up in the countryside, the way John did. I grew up in Juba, the most important city in Southern Sudan. My family—my father, my mother, my little sister, Tabitha, and I—lived in a compound with another family. Our house had a roof made of dried, thatched grasses and three rooms—a kitchen and two small rooms where we slept and, during the long rainy season, where we played. During the hot, dry season, everybody would bring chairs outside and sit in the shade. Despite the sweltering heat of the Equator, Sudanese people spend most of their time outdoors when it’s not raining.

On dry season evenings, when it was cooler, all of us children in the neighborhood would gather together to play tag. Sometimes we girls pretended that we were cooking, and we’d make plates and cooking pots out of clay, the way Sudanese women do. Or we played with dolls our mothers had made us out of scraps of old clothing.

My father was a policeman, but early in the morning before he went to work and before the scorching sun was very high in the sky, he and my mother would take Tabitha and me with them while they worked in a garden they had not far from our house. They grew mostly groundnuts. You call them peanuts, and we eat them just the way you do, as snacks or in peanut butter, which we also put in sauces or in our porridge.

Juba was a major port city on the great Nile. The longest river in the world, the Nile flows through the length of Sudan, then through Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea. Large boats heading south on the Nile couldn’t go any farther than Juba because of the rapids and shallows on the upper part of the river, so that made my town a busy port. Still, most of the roads in town were unpaved, and in the dry season, the dust kicked up by cattle being herded through town or by farm carts loaded with vegetables swirled through the air. In the rainy season, the roads were a muddy mess. The main paved road in town had been put in by the British when Sudan was a colony of theirs.

Sudan is the largest country in Africa, and there are hundreds of groups, or tribes, and many languages spoken throughout it. Like John, I am part of the Dinka people, the biggest tribe in Southern Sudan. Besides my tribe, I also belong to a clan. This is like a large, extended family whose members help one another. If you are Dinka, your clan is very important to your identity. John’s clan is the Bor Nyarweng. Mine is the Abek. My Dinka first name is Arual, the name my father’s family gives to firstborn girls.

My parents were Christians, and on Sundays we went to church. Before Christianity came to Southern Sudan, people there believed in witches, and they thought that illnesses came from being cursed or bewitched. Those beliefs still lingered when I was a child, even in cities like Juba.

Once, when my younger sister, Tabitha, was quite little, she got very sick. We could see where each bone in her body was connected because she was so thin. Friends of my mother’s said that her baby had been cursed. They told my mother that she needed to find a witch doctor to get rid of the curse. At first, she said, “No, I’m a Christian. I don’t believe in those things.” But when Tabitha got worse, my mother became frantic and gave in. She found a witch doctor who came and looked at poor little Tabitha.

“Someone has put magical bones on her body, and they’re killing her,” he pronounced. He said that only he could see the magical bones and only he could get them off. So my mother, in her desperation, hired him. But every time he came, he would leave Tabitha in her sick bed and walk around outside our compound.

Now in Juba there were no trash collectors, so people threw their trash outside the fences that surrounded their homes. When the witch doctor walked around outside, he would come back and lean over Tabitha and suddenly pull some kind of bone away from her. To my mother, those bones looked suspiciously like garbage people had thrown away. “Go away, and don’t come back,” she told him. Instead she prayed that God would heal her baby, and after some time, Tabitha recovered.

I was a little child then, too little to understand how sick my sister was. Also, like all small children, I thought my parents would always keep us safe. Most of what I remember from my first five years in Juba was the happy sound of people in my family and neighborhood. My parents loved me, and every night when I crawled into my nice metal bed with the comfortable mattress on it, the world seemed like a good place.

I didn’t understand that Southern Sudan had been a dangerous place for decades. When my parents were children, there had been a war between the southerners and the Arab Muslims who dominated the government in Sudan. That war ended with a treaty, and for ten years peace had kept life calm and allowed people to settle and prosper. But trouble started brewing again just after I was born.

The southern people were angry with the Arab government about a number of things. One was that the government planned to build a canal into the great swamp called the Sudd. The canal would carry the water away from the south to the Arab Muslims in the north and on to Egypt. Also, prices of critical supplies such as oil, bread, and sugar had risen because of the policies of the government in the capital city of Khartoum. Most important, the government had imposed Muslim law on the whole country, even though we black Africans of the south weren’t Muslim. The Arabs had never had much respect for us. They treated us as if we were beneath them, as if we were their servants.

In Juba and in other cities students protested against the government, and some were killed in the riots. Men in the south who were fed up with policies that favored the north formed the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, and fighting flared in the countryside between the SPLA, as we called that army, and local militia groups that the government had backed. But I wasn’t paying attention to any of that. I was just a girl of five, playing with my sister and my friends, expecting life to go on the way it was forever.

John

War came to my homeland when I was thirteen years old. We had been expecting it, but nevertheless it came as a shock when my village was actually attacked.

The Dinka had heard omens of war for a long time. Many people still believed in spirits that lived in animals and plants, and these spirits spoke to them about the coming of a very bad time. My parents told me one story just as they had heard it. They said a tortoise spoke to a man on a path outside the town of Bor. Among the Dinka, the tortoise is believed to be very smart. The tortoise told the man, “I am sent by the Lord. I bring you news of doom. Your country, Southern Sudan, will be destroyed.” The tortoise said the Lord meant to punish the people of Southern Sudan for being unfaithful, and it gave the man three choices. “One is drought,” said the tortoise, “and if you choose it, I will punish you by withholding the rain. If you do not choose that, I will punish you with flood. And if you do not choose that, I will punish you with war. Now, you must choose.” The man was frightened and ran away. The tortoise yelled at him, saying, “You must answer me! You must choose!” So the man chose war.

The man told everyone what the tortoise had said. The people of Duk Payuel, the village where my family was living at the time, debated whether the man had made a wise choice. Some argued in favor of drought. They knew they could survive because the Dinka have weathered many a dry spell. But drought meant famine, which would hit the women and children the hardest, so the villagers rejected that choice. Some argued in favor of flood. They knew the Dinka could survive because they could catch fish as the swamps filled with water. But floods meant our precious cows would die, so the villagers rejected that choice too. Most of the people in my village finally decided that the man had chosen wisely, but everyone kept talking about what the tortoise had said.

A month or two later, a crow landed on the shoulder of an old woman who was sitting making rope in the shade of her house. The crow gave her the same choice: drought, flood, or war. The woman didn’t know what to do, so she said nothing. The crow flew away.

Then a prophet had a vision. This man, named Ngun Deng, lived among the Nuer, a neighboring tribe. He saw bad things in the future. War would come to Southern Sudan, he said, and many would die. In the end, Southern Sudan would defeat the enemy, but it also would suffer defeat. Then he spoke a final prophecy: “Yours will be a generation of black hair.” The elders in my village debated his meaning. They decided he meant that the oldest and youngest would die. The oldest had gray or white hair, and the youngest had little or no hair. Only the black-haired young people would live, and they would see many troubles.

It was such a terrible time. People believed the words of the tortoise, the crow, and the prophet. Then one day the sun glowed blood red. My mother said it meant that blood would flow. “People will fight, and there will be lots of killing,” she told me.

At the time, I did not know much about my country’s history. Anyone who studied the early years of Sudan might have seen civil war in its future. Britain granted Sudan independence in 1956. The new nation brought together groups of people who had little in common. Arabs who practiced Islam and spoke Arabic dominated the northern half of Sudan and the capital, Khartoum. Black-skinned tribes who were either Christian or practiced traditional religions and who spoke dozens of languages dominated the southern half. At first, southern citizens saw little change in their daily lives while living in their new country. In the early 1980s, however, when the national government, dominated by northern Arabs, tried to impose Islamic laws on the entire nation, civil war broke out. Northern soldiers stormed into southern villages to quell the violence, but the fighting raged on. The northern armies got the best of most battles because they had more soldiers and guns and all of the airplanes. Those armies drew near shortly after we heard the prophecies of war.

I remember the night the soldiers came to Duk Payuel as if it were yesterday. The first sound I heard seemed like a low whine or whistle. It rose from far away on a moonless evening as I tried to sleep on the floor of a hut. About a dozen boys and girls shared the hut with me on that hot and sticky summer night in 1987. As government soldiers shelled and burned the countryside and airplanes strafed and bombed the villages, refugees moved south. Some came to Duk Payuel, and that is how I came to share a hut with strangers. My parents and other adults slept on the ground outside.