Полная версия

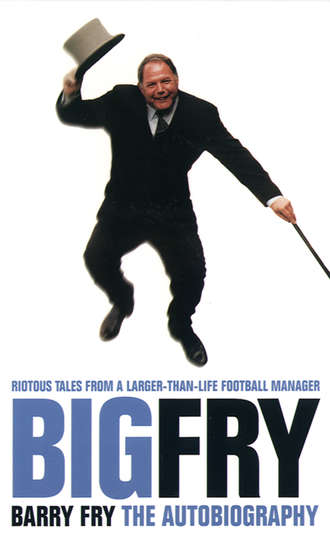

Big Fry: Barry Fry: The Autobiography

Throughout my school years I was never interested in any of the lessons, only in sport. I used to get the slipper a lot. When I was aged 11, and in my first year at Silver Jubilee, one particular teacher who hated my disregard for education would say, ‘Come out here Fry!’ and I would say, ‘No.’ In those days the desks had ink wells in them and in one of this gentleman’s lessons I threw one at him. But this prank rebounded horribly when he sent me to see the headmaster.

‘Right Fry,’ he said. ‘You’re not playing for the school team on Friday.’

He could not have taken a worse course of action. Six of the best with the slipper would have been preferable. I begged him and cried my eyes out, but all to no avail.

That slaughtered me. I was captain of the school team and became a prefect, to be identified by the red and white braid on the black jacket of the uniform, later on in life. I was urged by the headmaster, Jack Voice, to put as much effort into education as I did into football and I determined to at least try during lessons. I began to get a prize a year for English, not because I was ever going to raise a challenge to William Shakespeare, but because I tried. It was made clear to me that if I didn’t concentrate and I became a pain in the arse I wouldn’t be allowed to play football. There could have been no greater incentive. Really, I had no interest in school whatsoever but if they had told me to jump over the moon in order for me to play football I would have jumped over the moon.

I missed the one solitary game and that was it. It taught me a lesson. It was ‘three bags full, sir’ after that.

Jack Voice was the one who put me on the straight and narrow. He certainly knew my Achilles heel and he had no trouble with me after that. He said he was aware that I didn’t like school but emphasised that while there were lads who succeeded at football there were a lot more who did not and therefore I should try because you would never know when you needed to fall back on education. As I am only too well aware now, for all the stars such as the Beckhams and Owens of today, there are a million who get released and hit the scrapheap.

All the teachers encouraged me in the sporting arena because, after all, it was good for the school to have one of their pupils representing them outside. Whether it was cricket or football, whoever was in charge just gave me my head.

As a boy I once had a conversation with Stan Matthews. I managed to get onto his team bus and asked him to sign his autograph.

‘What are you doing here?’ he asked.

‘I’m watching you. It’s fantastic.’

He asked how old I was and I told him I was 10.

‘You shouldn’t be here, you should be playing. Practice son, practice.’ Stan has since passed away and I joined the rest of the football world in mourning over his death.

It soon became apparent to me that you can’t be a softie and be a good footballer but I remember being frightened to death at Pearcey Road one day. I was going home for dinner and suddenly became aware that a bloke was following me. I was convinced he was chasing me and wanted to murder me so I ran into the house of a couple who fortunately were in at the time. I didn’t want to go back to school. They had to get a kid called Brian ‘Trotter’ Foulkes to look after me, get me across the road and make sure I was all right. I must have been the youngest kid in the country with a minder. But eventually you had to look after yourself. As I got older and a bit more successful football wise, people who were not so interested in football thought I was cocky and big headed and all that. You always get bullies trying to pick a fight or sort you out and I fought like everybody else though with me it was an instinct, a reaction. I was always a scrapper, really, because you had to be to survive. The alternative was that people would walk all over you. I was as placid a kid as I am a man but when too much gets too much you hit out at people. I never went looking for a fight but I certainly wouldn’t run away from one.

Football being my only interest in life, I always got hot-off-the-press copies of Roy of the Rovers and Charlie Buchan’s Football Monthly. I would get up in the morning and hope that I was early enough to play Wolves v Manchester United at tiddlywinks and when I got home I couldn’t wait for dad to come round the corner. Now my kids do the same to me but I say, ‘No, I can’t. I’m mentally and physically drained.’ Dad must have had such patience. There are days for most people when you have been to work and you simply can’t be bothered playing head tennis. My little 10-year-old, Frank, will say, ‘Well just give me a few headers, dad.’ I tell him to kick it against a wall instead.

I used to say to my dad that I wanted a wall to kick a ball against and we didn’t have one. He got me this magic thing with a ball on the end of some elastic and you’d kick it this way and that and it would always come back to you. Mind you I broke a lot of things in the house. Mum went mad and dad would tell her to leave me alone. They had World War III and I would sneak off.

I never knew the meaning of being bored. I either played football and when I came back it was time for bed, or I played a full league table of tiddlywinks. There would be a goal scored and me making an almighty racket, while mum and dad sat there listening to the radio in the other room. The decoration in our front room was rosettes and other football memorabilia. Normally parents wouldn’t allow those things in the room where guests were entertained, but my mum and dad were very understanding. The front-room carpet would be covered with all my ‘players’ and my parents were so considerate that if they wanted to go to the toilet they would walk all the way round the house to avoid the living room so that they would not disturb my game. The sacrifices they made – you don’t appreciate it at the time. My bedroom was also full of Wolves momentos.

When I was 12 there was a brilliant article in the local paper. Because I’d been to Wembley so many times since turning eight, the only thing I ever dreamed about was actually playing there. In this feature my dad was quoted as saying, ‘It’s Wembley or bust, isn’t it son?’ Dad had taken me to internationals, FA Cup Finals and amateur cup finals between the likes of Crook Town and Bishop Auckland, so by that time I had gained a real feel for the place. There were the old songsheets and such like and I just loved going to that magical place.

Mum and dad were bringing up their only child in a sublime area for sporting activity. The local hamlet of Elstow was proud of its pristine village green and I would play cricket as well as football there. Dad was also trainer of Elstow Abbey, a men’s team in the Bedfordshire and District League. I played for them at the age of 14 against all the village sides and I would have to look after myself although some of the lads, particularly our centre-half Maurice Lane, and Charlie Bailey, would not allow the opposition to take liberties with me. They didn’t mind me being kicked, because that was all part of the game, but if there was any sign of a rough house they would look after me. If you were in the trenches you certainly wanted Maurice with you. I appeared for them in a cup final at Bedford Town’s ground. At school at Pearcey Road I had played in a cup and league-winning team, scoring 60 goals in one season, and was in the Bedford and District team when I was eight. When I moved up to Silver Jubilee School I was soon into the Beds and District Under-13 and then Under-15 teams. It was a period in my life when I walked to school and ran home!

Dad, as always, encouraged me in my football passion. He would come and park outside school in his lorry and watch me play and he was even known to have climbed up a GPO pole to get a good vantage point. These were Friday afternoon matches, after the last lesson in school, and in my playing days in the Bedford and District side we played on Saturdays and went all over the country together.

At 14 I was picked for London Schoolboys. I know the saying that Big Brother is watching, but how the hell a boy 56 miles away in Bedford is selected to play for London is beyond me. Then, in what was a wonderful year for me, I had trials for England Schoolboys. They were organised as Southern Possibles v Probables and Northern Possibles v Probables and then South v North and for the first of these I was down as a reserve. As luck would have it, somebody didn’t turn up and I got a game. I must have impressed the right people because I was called up for the next trial and then the other. As a kid you never know how these things come about, but it was announced in school assembly one day that I had been picked to trial for England. I went on to play for England schoolboys six times and the most memorable of these was in front of a 93,000 crowd at Wembley against Scotland on Saturday 30 April 1960. Among my England team-mates were Len Badger, the Sheffield United full back, Ron Harris and David Pleat, while George Graham played for the opposition. My international selection was terrific for Silver Jubilee school because I was the only Bedford boy ever to have been picked for England. A convoy of buses left the school for Wembley and later the headmaster insisted on a photograph being taken of the entire school with me wearing my England cap.

I used to wonder what it was all about when the other kids would say they were going to Blackpool for the week or Great Yarmouth for a fortnight, for we never had a holiday. Never once. Aunts, uncles and mates all had cars and forever seemed to be darting here, there and everywhere, but for me it appeared that the Bedfordshire boundary lines indicated some kind of electrified fencing to keep us in there, with the rest of the world a no-go zone. I never knew why this was the case but it has since become clear. After all the years dad worked he was allowed four weeks’ holiday, then five, then six but never used to take them. What he did instead was to build them up, because he felt that at one time he might have to pack up work, or take a long period of time off, to look after mum. He had to look after his family and do the best he could for them. When retirement came upon him it became apparent that he could have finished a year earlier because of all the time due to him that he had in the bank.

Mum, Dora, died a month after my son Mark was born and it was very sudden. It was as though she had been clinging on to life just so that she might see him. I was at Bedford Town as a player and I worked for the chairman, George Senior, in the mornings. He had a cafe down the London Road and had all these breakfast rolls to get out for a lot of local companies. I couldn’t cook, so I was just serving or cutting rolls and putting cheese and ham in them. About 7.30am dad came in with Maurice Lane. He and Maurice often popped in but this day he came in the back way. He never did that. He said he’d been up all night with mum and she was in pain and at the hospital in Kempston, where I lived at the time. Dad said mum had said that I was to get on with work, but I wanted to go to the hospital to see her. He said there was nothing to worry about, but it did concern me. After half an hour I said I wanted to go. At Bedford I used to go round in a van collecting from the sale of lottery tickets. This night I went to hospital with dad, a week before Christmas on a Friday, and mum was obviously in a lot of pain. She had her face screwed up and complained of feeling cold.

I was in the room alone with her for a while and she kept saying that I had to go to work. I felt very uncomfortable. When dad came back I asked if he’d seen the nurse to sort out her coldness and he just said: ‘No’. The bell ending visiting hour was going in no time, so I kissed her and she said: ‘Go to work.’ Dad had to pick up her mate from Hallwins. She was a Scottish lady called Jenny Denton who was getting the bus to Biggleswade from where she would catch the train to Scotland for New Year, so mum was on about dad not forgetting the passenger and me not forgetting to go to work. I went first. Dad had a car then, which I bought for him. I just wanted to go home and not go to people’s houses. My house was only five minutes away. I walked in the front door and Anne, my first wife, said the hospital had just rung to say my mum had died. My reaction was to turn round and put my fist through a pain of glass in the window.

‘You’ve got it wrong,’ I said.

My dad wasn’t on the phone. He worked for the company for 40 years and never had a phone. Can you believe that?

I was 26. I didn’t even know mum was ill. My first thought was about dad taking this lady to Biggleswade, so I jumped in the car, got there taking one route to find the bus for Scotland had gone and coming back another route without seeing my dad. I stopped at a club, run by my mum’s sister, Alice, which my dad sometimes popped into for a drink. I saw Auntie Alice and asked if she had seen my dad and she said: ‘No, why?’ I said: ‘My mum’s dead.’ She screamed. I was in a daze. ‘Our Dora’ was all she could say. I was trying to find my dad and couldn’t. I called at a couple of pubs in which he would usually be having a drink with his mates but nobody had seen him. They all knew he was going to take this woman to Biggleswade. I just went home. I was telling Anne the story when there was a knock on the door and it was my dad.

‘I’ve been looking for you everywhere. Mum’s dead.’

‘Yeah, I’ve been expecting that,’ he said.

Just like that.

We went back to the hospital. Upstairs the curtains were drawn and by this time it was 10 o’clock at night. I could hear people near mum breathing and you didn’t know she was dead. I went a bit crazy. Dad calmed me down and took me to the pub opposite the hospital. He said there was nothing I could have done. That was the way she wanted it. She knew she was bad but just tried to forget about it. She had being going to London for years for chemotherapy treatment and there was no way you could have known this unless you had been told. She was always as white as a freshly-starched tablecloth so there was no reason to suspect that anything was wrong.

I was due to play for Bedford the following day and I said to dad that I would have to pull out of it. He fixed me with a stare and said: ‘You won’t. The last thing your mother said to you was to go to work. That’s your work. Now go to work.’ I did, but I may as well have been on Mars for all I could remember about the game. I didn’t know whether I had had a touch, scored or not scored; whether we won, drew or lost. I was in a daze. It had been important to dad that I carried out her last wish and, in retrospect, I can understand his attitude to the whole situation. Whatever you give to your parents should come naturally and not because they are dying and you want to tell them again that you love them.

For 25 years I just blanked mum’s death from my mind. I broke down terribly at her funeral. She is buried in Elstow and, even though I think about her a lot, I don’t go to her grave. I can’t explain the reason. People deal with the loss of somebody close in different ways and I have my own way. Dad, Frank, still lives in Bedford. He comes to all the games, with my son-in-law, Steve, taking him along. Though I live in Bedford I don’t see him as much as I’d like to. He’s a great father like that because where a lot of old people moan that you should go and see them, he never makes reference to it. He knows that I’m very busy both at work and with my family.

I’m afraid that I do not possess any of his qualities and I wish I did. He is a lot better a man than I will ever be. He has got principles, I have none. He has respect, I have none. He is disciplined, I am not. And, talking of discipline, he is responsible for having made me such a good runner. Whenever I crossed him as a youngster he would take off his belt and threaten me with it. He never used it. The threat was always enough and I would be off like greased lightning.

I heard him swear only once, and that was when I had the audacity to laugh when those dreadful glasses of his fell off when he went up for a header one time. I got a clip round the ear for that for good measure.

It will be a source of some amusement to those who know me that I grew up never once hearing a swear word in the house. I have no other vocabulary and I cannot offer an explanation for this. When I was at school everybody thought I was a cockney. The teachers used to tell me that I was uncouth, whatever that means. I didn’t even know what a cockney was. Now that I do, I am happy to issue an invitation to those of that breed who wish to learn from the Fry Academy of Blasphemy.

CHAPTER THREE

New boy at Old Trafford

During that 12-month spell when I was playing for England Schoolboys I could have signed for any club in the country except, perversely, Wolverhampton Wanderers. The Molineux management was just about the only one not to make an approach of any kind, and had they done so I would have found myself in something of a dilemma.

I trained with Bedford Town and their manager Ronnie Rook, the old Arsenal centre-forward, wanted me to sign for them, though I soon had reason to fix my sights much higher. During the holidays, as a 14-year-old about to leave school in the summer, Manchester United’s chief scout Joe Armstrong invited mum, dad and me up to Old Trafford for four days. They wanted to sign me as an apprentice professional and took me up there to show me the kind of digs in which I would be resident. At this stage in life I had, of course, never been away from home and it was important that my parents were happy with the projected arrangements.

On the particular day of our arrival United had a youth game. Joe introduced us to the assistant manager, Jimmy Murphy, and the boss, Matt Busby. They looked after my parents while Joe took me along to Davyhulme Park Golf Club, where the lads were having a pre-match meal before the game. Such meals in those days consisted of a steak with an egg on top and I duly sat down to enjoy the fare. You dare not have a steak these days – it’s pasta now, but back then the menu was different. I sat next to Nobby Stiles, who was captain of the youth team, and in less time than it took to eat the meal he had sold Manchester United to me. He had so much enthusiasm for the club, with dedication and loyalty gift-wrapping his every word in praise of Joe, Jimmy and Matt. I joined the lads on the coach back to Old Trafford, was introduced to everybody and just wished that I was playing that night. I could not have been looked after any better. I was in the dressing room and then behind the dugout and was made to feel part of the set-up from the word go. I was to discover that this was the way they always did things at Old Trafford. The following night we were taken to the top show in town in Manchester and in the middle of the third day my parents took one look at their starry-eyed son and asked what I wanted to do. I was due at Chelsea and West Ham the following week just to have a look around, but I said: ‘I don’t want to do anything else. I want to come here.’

Mum broke down in tears. My parents were brilliant. They never offered unwanted advice like taking some time to think about it, nor cajoled me into joining a London club much closer to home. They made me feel that the decision was mine and mine alone but, in fact, Manchester United had made my mind up for me. Their public-relations exercise was first class. I had watched that youth team match among a crowd of 35,000 and a three-quarters full Old Trafford was more than enough to impress any aspiring youngster. I had Jimmy Murphy telling me that I would be out there playing the following year and the package was sold lock, stock and barrel without me even having kicked a ball during our stay. When Joe Armstrong came to our house with the invitation to Manchester, he might as well have issued the same invitation to Mars. I didn’t know where Manchester was – I was never very good at geography at school. It may have been a foreign land as far as I was concerned. Joe had watched me playing for England Schoolboys and, after the games, would always come over and shake hands and tell me that I had played well. But he was just one of many influential people who used to hang around and I was offered many things. My family had never been used to having money and it was something I didn’t care much for at that stage. That was a good thing because it meant that a purely footballing decision was to be made.

Afterwards the lads would ask how much you had got for going there, saying they had received this, that and the other, but I literally did it for nothing other than the privilege. Dad later told me that after I had agreed to sign they sent down railway tickets so that he could watch me in whichever match I played.

My last few months at school felt interminable as I savoured the prospect of going to Old Trafford. What I have never understood is the ‘local boy done good’ factor didn’t register with the Bedford newspapers. I’d lived there all my life and yet there was never a mention of a move which had to reflect well on the town. I have since been involved a lot with the press and so I know the way it works. For instance when I was at non-league Hillingdon, I was God. I could walk on water. I saved them from relegation and we beat Torquay in the FA Cup and hardly a day went by without there being some mention of me in the paper there. But for some reason, the locals in Bedford missed out on the good news.

Anyway, northbound I went. My first digs were with Mrs Scott at Sale Moor, a lovely district of Manchester. She lived there with her sister and both were absolutely nuts about Manchester United. A lad who had played for Scotland Schoolboys called Mike Lorimer also resided there. We would get the bus in to training every day and the whole thing was the complete opposite of what I had expected. We would arrive at the ground at nine o’clock having had a breakfast of a raw egg in milk. This would come up more often than it stayed down, but the club insisted on starting the day with this concoction and to make sure the rule was adhered to the landlady would stand over you while you drank it. I thought we would be playing football morning, afternoon and night. But the first task of the day was to help the groundsman sweep the terracing. Then you would clean all the baths and toilets before moving on to clean the boots. You did everything, it seemed, except play football. We moved on to training in the afternoons but I hated those morning chores. Of course it was all part of the education process, but in those days I never cleaned my own shoes, never mind someone else’s boots. It was something of a disappointment. You leave school and think ‘Great, I’m going to be a professional footballer with Manchester United’ but the reality is that you’re like some old cleaning lady with mops, buckets and brushes. Any small consolation I was able to take from this unexpected facet of the occupation was that I was at least cleaning the boots of two immortals in Nobby Stiles and Johnny Giles. For the first couple of years they looked after me wonderfully. The routine was that the new kid on the block would have two more senior players assigned to him and I was fortunate to have this pair.

United had a reserve team, A team, B team and youth team and I went straight into the youths, whose only games were in the Youth Cup, and the A team, having virtually bypassed the B team. At the end of those first two seasons we went to Switzerland for a tournament in Zurich which featured all the big European teams. I was 15 and 16 and, suddenly, a whole new world had opened up to this former Bedford ‘inmate’.

Travelling to that first tournament entailed me getting onto an aeroplane for the first time in my life and it was not until some time after that I was able to get my feet back onto the ground, because we won the tournament and I scored the winning goal against Juventus. I was through on goal and smashed the ball into the net and when, in celebration, I went to retrieve the ball out of the back of the net to take it back to the centre circle, it caused an affray. Half of the Italian team jumped on me and I emerged with half of my shirt missing and my number eight floating away on the breeze. This was my first bitter experience of Italians and there were to be more in later life. We won the tournament the following year, too.