Полная версия

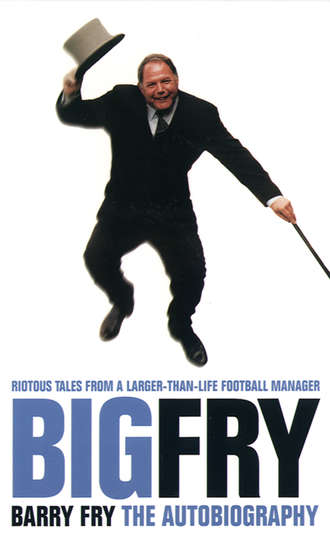

Big Fry: Barry Fry: The Autobiography

‘You, you bastard,’ he’d say. ‘I didn’t want to see you.’

‘Keith, I’ve got no money,’ I would plead.

With that he’d open his briefcase and pull out a wad of notes.

‘That will do you for now. Stop pestering me.’

He was a dream chairman at first. Then he went inside and you can imagine what happened then. Because I was having to sell all my players before the transfer deadline, we tumbled from top of the league to eventually finish fifth. We would have won it if we had all been able to keep together, but a different issue altogether had emerged. It was no longer about winning. It was about surviving.

I couldn’t pay the players any wages. Because we owed the players so much money, I had to turn to my old mate George Best. I told him that we had floodlights, hadn’t paid for them, were in the shit, the chairman was going to prison and Harry Haslam, manager down the road at Luton, had said he would provide us with opposition in a friendly.

Bestie, good as gold that he is, came and guested for us and pulled such a big crowd that we were able to pay the players the six weeks wages they were owed. George never got a pound note for his friendship, loyalty and generosity and it’s rewarding for me to reveal the other side to his character when all he took for so long was so much criticism.

At the end of the season we were kicked out of the league. We broke our necks to get out of trouble but because our guv’nor, who had all the shares, was inside, and we had debts that we could not possibly honour, we were sent down a division. From there Dunstable Town went into liquidation. They formed a new company but after Cheeseman went I had five or six different chairmen who came in to try to save the club but none of them succeeded.

In the end Bill Kitt, a local man who had made a few bob and who was the latest in the line of possible saviours, said he was going to give all the players a tenner – only the ones who played, not the substitutes – and after this, his first match, away at Bletchley, I was asked by the press what I thought about his generous gesture.

I went up to the boardroom where Bill was having a drink.

‘Do you want a whisky, Barry?’

‘Whisky?’ I huffed and threw it all over him – what a waste of a drink – but I was Jack The Lad and raving, mocked his offer of a tenner and then, I’m afraid, I got hold of him. I should not have. Next morning the club called an emergency board meeting and sacked me. But what was I to do? After all I had been through I could not stand idly by and be told that my players were going to be paid a measley £10 for their efforts. It was a sick joke. Bill and I are the best of friends now but, at the time, I could have knocked his lights out …

There had been a long period of uncertainty before Cheeseman and his crew were all arrested. What Cheeseman had done was this. When he was at the football club he used all the names and addresses of players, officials and supporters – as many names as he could gather – to fund his other businesses to get loans out.

He was paid by the council every month a substantial amount of money. He was a director of a construction company with many contracts, and the beauty of these contracts was that he was being paid by the council so that it was rock solid, gilt-edged money paid on the button. The trouble with Cheeseman was that he was never happy with just a good, going concern like his construction company. He always wanted something else.

He got the finance manager to do a few straight loans and then they became fictitious. The guy just got him the money the next day. It wasn’t a problem. The monthly debits were coming in regularly on a standing order for the straight ones but as the invented ones got bigger and bigger in number, alarm bells must have started to ring everywhere.

At one point the man in the respectable position tried to get out of the mess but Cheeseman told him that if he turned his back on the scam he would stitch him up by saying that it was he, and he alone, who was responsible. Poor bloke. One minute he was getting record sales and pats on the back for doing great business; the next he’s in the deepest shit.

He was a nice guy who simply got in over his head. He couldn’t get out of it. His assistant manager obviously knew about it and it was clear to him and everybody else who knew the fall guy that he was heading for a nervous breakdown.

Cheeseman got him out of the country and into his place in Spain where, after a week, he called to say that he was enjoying it. So Cheeseman would tell him to stay another week, and another week, and of course the manager’s absence from the office meant that paperwork was piling up.

The managing director, the man Cheeseman had had by the throat in my office, arrived at the office one day to find a lot of accounts which had not been paid. So he began telephoning a few people to tell them that they had missed out on the current month’s repayment instalment on their £2,000 loans. A typical conversation would follow.

‘What £2,000 loan?’

‘Well, that £2,000 loan you have had for the past seven months.’

‘But I haven’t got one.’

‘But you must have. You’ve been paying it.’

‘I haven’t been paying it. Not me.’

There were more than a few too many of these. I lived in Tiverton Road, Bedford then and was to discover that there were eight loans in variations of my name, Fry, Friar, Frier and so on.

The beans were spilled when the assistant manager broke down in tears and told his managing director precisely what had been going on.

In 1977 Cheeseman stood trial at Bedford Crown Court for having made bogus loan applications totalling nearly £300,000, using the names of the club’s players and others he got from the phone book. He was jailed for six years.

Soon after his release he was jailed for three years for blackmailing a bank manager into advancing him £38,000 against fraudulent US bonds, an Old Bailey case in which the Duke Of Manchester, Lord Angus Montagu, stood in the dock with him on criminal charges. The Duke was acquitted and left court with the judge’s admonishment that he had been ‘absurdly stupid’ ringing in his ears.

In 1992 Spanish police raided Cheeseman’s villa in Tenerife and arrested him. He was wanted for extradition on charges of laundering £292 million worth of bonds stolen from a City of London messenger in the biggest robbery in history. At the time it was thought the bonds were unusable, but Cheeseman was arrested at the request of the FBI, who were investigating attempts to launder them.

He jumped bail a few days after an associate of his was shot dead in Texas and, two months later, when a headless body was found near a layby in Sussex, it was suspected that Cheeseman might have met a similar fate.

It was at this point – I was by then manager of Maidstone – that I received a bizarre telephone call from the police. The conversation went like this:

‘Barry Fry?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you used to be manager at Dunstable?’

‘Yes.’

‘Was Keith Cheeseman your chairman?’

‘Yes.’

‘Could you recognise Mr Cheeseman?’

‘Of course I f***ing could.’

‘Could you recognise Mr Cheeseman with no arms?’

‘Yes.’

‘Could you recognise Mr Cheeseman with no legs?’

‘Yes.’

‘But could you recognise Mr Cheeseman without his head on?’

I checked that the calendar was not showing 1 April before replying: ‘Sorry, mate. I didn’t know him that bloody well.’

About a month later I got a call from the same officer.

‘Mr Fry, I am pleased to report that the body we found is not that of Mr Cheeseman. It is of somebody else.’

I obviously had not seen him for ages and I could not resist asking what Mr Cheeseman had been up to. The officer told me: ‘He deals with the wrong kind of people.’

I hadn’t heard from him for years until, three months into my tenure at Peterborough in 1996, I picked up the telephone.

‘Hello my old son,’ came a familiar voice on the other end. ‘How are you doing? You’re in a bit of trouble aren’t you?’

It was Cheeseman again. I said that we hadn’t got any money, if that was what he was referring to.

‘I’ve got plenty for the both of us, Barry.’

I asked what he was doing at that point in time.

‘A bit of this and a bit of that but I won’t talk over the phone, I’ll come and see you.’

We arranged that he should come to our home match the following Saturday and that he would bring his lady for lunch. He looked good, but always had done. He was invariably immaculately dressed in a designer suit, crisp shirt and eye-catching tie and always wore shades.

He said he had been in America and last weekend had been with Gloria.

‘Gloria who?

‘Estefan, of course.’

Then they had gone on to a party and Frank said this and Frank said that.

‘Frank who?’

‘Sinatra.’

Of course. Now he had become a great namedropper. He gave me his business card, which prompted me to ask what he was currently doing. He said that he was making fortunes through setting up venues for pop concerts and that was why he had been anxious to meet up with me at Peterborough.

‘You want some money, don’t you?’ he asked, rather needlessly.

I told him that we were desperate for cash.

‘We’ll hire out the ground. I’ll bring some top people over,’ he said.

‘Keith, I’m not being funny but it might be a flop.’

He assured me that everything would be all right because he would pay the money up front and he proceeded to stay in Peterborough for two months. He made it clear that he wanted to buy the club and I arranged meetings with all the directors. He came to league games and youth games and talked to this person and that within the club. He liked the fact that we owned the freehold on the ground and that we had several promising young players who would ensure progression on the playing side.

He got really into it, bringing his accountant into things and acting as though it was a foregone conclusion that he would own the place. One or two people were getting a bit hot under the collar and then one night he invited us all out for a meal. He talked freely and openly about the City of London heist, asserting that he got on with all the coppers because he knew them so well, claiming kinship with the mafia bosses and asking if we had seen the television documentary about him.

Nobody had seen it, but I later viewed a video copy that he had given to me. I, in turn, showed it to all the directors of the club and to anybody who is squeamish or a bit nervous it is very frightening. It centres on the world’s biggest robbery and, after they had seen it, there was no way the board wanted him in their club.

The round-up to the piece is an interview with him in which he is asked: ‘Well, that’s the world’s biggest robbery. Is that you finished with crime now?’ He smirks and says: ‘No. I want to top that.’

Well how do you top it?

The atmosphere in the boardroom when they came to discuss the proposal was icy. It was dead in the water and Keith knew that. He had had his card marked and when he called me to ask what had happened I told him.

‘Keith, you frightened them to death.’

He said that he had to go to Luton and would pay a social visit to me at home on the way back to his hotel before I set off for my day’s work at the club.

As he was nearing my place he called on his mobile phone to check my exact location and I asked my great pal Gordon Ogbourne, who has been with me for 20 years as kit manager at various clubs and whom I trust implicitly, to go to the end of the drive and just wave him in.

We had tea and sandwiches and he said that he was not prepared just to accept what had happened. He was not giving it up that easily. He wanted the club and was going to get it.

After half an hour of reinforcing his ambition we both decided that it was time to go our separate ways for the day ahead and I said that I would follow him out. We reach the main road from my drive and he turns left, I turn left. We get to the lights and he goes straight on, I go straight on. At the next lights he turns left, I turn left. Then as he goes straight on to pick up the A6 to Luton, I turn left to get on the A421 to Northampton. I had no sooner reached this main highway through a little village than my mobile phone rang. It was my wife, Kirstine.

‘Stop at the nearest phone box and ring me back at the neighbour’s house over the road,’ she said with some urgency.

I protested and said that whatever she had to say she should just say it.

But she insisted. ‘Barry, I ain’t being funny. Stop at the nearest phone box and ring me back. Immediately.’

Realising that something strange was happening, I did as she said.

What’s going on?’ I asked from the phone booth.

‘You ain’t going to believe this, Barry. I’ve got our neighbour over here. I think you’d better come home. She has had people with guns with telescopic sights in her garden. They are following you.’

‘Following me? I’m in a phone box. There’s nobody here.’

‘I don’t mean you,’ she said. ‘I mean Keith.’

So I put the phone down on Kirstine and called Keith on his mobile. I relayed the message that when he pulled into my driveway a white van turned up in the drive of the house opposite and that there were men with guns.

Understandably, the neighbour was petrified because she could see what they were tackled up with. They even knocked on the door and she didn’t know whether to answer it or not. She decided not to, but they said they were police and that she should ring the station to verify their presence.

She did this and the officer who answered the phone said that he knew nothing about it. Well, she was in a panic now and didn’t know what to do. Thankfully, with two men with rifles on the other side of the door and her quivering, her phone rang and it was a return call from the police to say that, contrary to the information previously given to her, they did know about the situation. It was nothing to do with them, said the caller, it was Interpol.

Armed with this information, she opened the door to them and they presented their badges with the reassurance that they were just observing somebody.

In my conversation with Cheeseman I continued.

‘They’re following you.’

‘Not me, mate,’ he replied with typical bravado. ‘You must have been up to no good Barry.’

That’s the way he plays it. So bloody cool.

I met him the next night at the home of Rinaldo, an Italian gentleman who lived in Peterborough and owned a night club of the same name. Cheeseman wanted to buy his property which was on the market for £750,000. That was the last I saw of him for some time.

A couple of months after that I had a phone call, again from the police in London, to ask if I had a phone number at which they could get hold of him, but I could not help them. The officer said there had been a few complaints about Keith and they were searching for his whereabouts. Did I have a previous address for him? All I could tell them was that he had stayed at The Butterfly Hotel, and that I had a mobile phone number for him which was no longer applicable.

Then I had the manager of The Butterfly phone up.

‘You know Keith Cheeseman, don’t you?’

I said I did (only too well, by now).

‘He’s left an unpaid bill of £3,500 here.’

I could not help but laugh. Uncontrollably. Then a finance company (ho-ho) called with an all-too-familiar opening line. ‘Do you know Keith Cheeseman?’ Apparently he hadn’t paid the last five instalments on a car loan.

Keith Cheeseman is the greatest conman I have ever known; possibly the world has ever known. When you were out with him he always had loads of readies and he was the most generous man with tips you could wish to meet. One day at The Dorchester Hotel in London he gave the porter £20 just for taking the bags to his room. A waiter brought an ice bucket and he gave him £20. Then he gave a taxi driver a £20 tip when he took us less than a mile round the corner.

He was such good company that you would have thought butter would not melt in his mouth. Yet in a roll-call of 20th Century villains he would have to be near the top of the league.

If my first job in management was a roller-coaster ride, it could hardly have prepared me better for the long and winding road ahead.

CHAPTER TWO

‘Practice son, practice’

Pilgrims Way, Bedford, was part of a council estate of prefab housing originally designed to last for 10 years, though they must have been made of strong stuff because my father actually lived there for 49 years and 11 months before they finally brought in the bulldozers. For me, it was wonderful to be resident there as the most popular kid in the block, entirely due to our being the only household to possess a proper football. My dad worked as a Post Office engineer for 40 years while mum was employed at a television rental company called Robinsons and also for, as I called it, the ‘knicker’ factory. This was, in fact, a lingerie outlet called Hallwins.

I went to Pearcey Road School from the age of five and it was here that my lifelong obsession with the wonderful game of football began. I got into the school team when I was eight and in those days I used to wait for dad after coming home from school, looking anxiously over our little fence in readiness for him to appear on his way home from work. Football quickly consumed my entire young life. I would say to dad, ‘Will you play football with me?’ almost before he could get to the front door.

There were plenty of fields down at the bottom of the street and it was greatly pleasing that dad encouraged me and all the kids round our estate to kick around with a football. We were the first to have a posh ball with laces and it was amusing at Christmas time and when the kids had birthdays. They would all come round to our house and ask, ‘Can Mr Fry pump our ball up?’ They didn’t know how to lace it up, either, and dad was an expert on that.

I was an only child and it must have been comical for the neighbours to see dad and I emerge from our front door. He was like the Pied Piper. As we walked down the street, bouncing the ball, the other kids would emerge, one by one, and by the time we had reached the fields there were enough bodies for a 12-a-side game. We would use milk bottles or jackets for goalposts and the games were never-ending. Dennis Brisley, who was a bit older, was one of the boys I was friendly with. He just used to love football and played until he was 45. He was a super-fit man. Ken Stocker, another one of the knockabout boys, was in my school team and it’s a coincidence that two of my best pals, he and Dennis, were right wingers. Tommy McGaul was another one of the crowd. He had two brothers and they all used to come down to the green to play.

Dad was trainer for the Post Office side as well as playing for them and whenever the GPO had a game I would take the day off school and go and support him. He was obliged to wear glasses because a bomb in the war had sent him flying, but it was frightening and almost farcical to see him playing in those spectacles. Born in Dover, he had been a navy man. Mum was from Jarrow and there was as much a contrast in their personalities as there was in their geographical roots. Dad was always the serious one, a stalwart of the school of rigorous discipline, whereas mum liked a joke a minute. Both had big families.

There had been no football on television in the days of my early youth and, anyway, we did not possess a television set. But in 1954 Wolves were to be shown on television playing Spartak Moscow in a friendly and I went to the house of a neighbour, Terry Mayhew, whose mother was Irish, to watch it. I was spellbound, mesmerised. Tilly Mayhew later told my mother: ‘I asked Barry if he wanted a drink and he was just oblivious to the question. He just kept staring at the screen.’ I became a mad Wolves fan, so much so that mum knitted me a scarf with all the players’ names on. I’ve still got it all these years later! I was besotted just through watching them on television. Billy Wright was my idol. Not only was he captain, but he was a gentleman and conducted himself correctly. Everything about him was pure magic. I kept a scrapbook on Wolves and a separate one dedicated entirely to Billy Wright. Among the team there was Swinbourne, Clamp, Deeley, Flowers, Delaney, Hancocks, Mullen, Murray and Broadbent. Peter Broadbent was another one of my favourite players. He had such grace about him. Their names were all on my scarf, but when it came to the captain he was given his full name. The stitching says ‘Billy Wright’. I don’t know why I loved him so much because he played in that unexciting position of centre-half. He was, however, the England captain and that may have had something to do with my boyhood admiration. I was also incredulous at how high he could jump for a little man. Dad was later to take me to London to see Wolves play whenever they came south.

You can imagine the scene then, years later, when I’m in a garage at Barnet, filling up my car. Another man pulls in, jumps out and he comes over to me and I instantly recognise him.

‘Hello Barry,’ he says. ‘You’re doing a wonderful job down at Barnet.’

It was none other than Billy Wright. Imagine, my hero says that to me! I was so awestruck that I nearly squirted him with all this petrol.

‘You wouldn’t believe this mate, but you’re my idol.’

He smiled. ‘I’ve been watching your progress down at Barnet at close quarters and you have done fantastic.’

I asked how he knew about what, to him, must have been such a rudimentary matter.

‘I only live down the road,’ he said.

So Billy and his wife Joy were living so close without my ever knowing, even though at the time I knew he was working for Central Television. I was further able to indulge my hero worship because, on occasions, I used to get to sit in the Royal Box at Wembley alongside Billy, who was a director at Wolves. He always looked after me in those circumstances.

My favourite carpet game as a kid was tiddlywinks, though I played it in a manner which can hardly be said to have been traditional. I turned the tiddlywinks into massive football matches – red tiddlywinks versus blue tiddlywinks; black tiddlywinks versus yellow tiddlywinks. I would put two Subbuteo goals at either end and this massive tournament would start and go on all day.

One of my earliest memories of football is of the so-called ‘Matthews Final’ in 1953, the FA Cup Final at Wembley between Blackpool and Bolton Wanderers. Dad’s football connections with Elstow Abbey and the GPO allowed him access to one ticket to stand behind the goal and he gave me a tremendous thrill when he announced that he was taking me. After our journey by train and tube he put me on his shoulders as we mixed with the thronging crowd and walked down Wembley Way. I was to remain in this elevated position – even though I must have felt like a sack of potatoes by half-time – right through the match. Dad wanted Blackpool to win it; everybody wanted Blackpool to win it because of Stanley Matthews. They may have called it the Matthews Final but I have never understood why because Stan Mortensen scored three goals.

I was the envy of all my schoolmates and, indeed, I have been at every Cup Final since. I was always very keen to collect autographs and after the matches I used to stand outside Wembley and try to figure out a way to get to the team coaches. I couldn’t get in because of those big doors. Then I discovered that if you went down one of the long tunnels from inside the stadium and avoided being stopped you would eventually get to the buses. So it became my practice to do this. Dad would be looking everywhere for me and it would not be until both buses pulled out, and I had got all the autographs, that we were reunited.

Another of my indulgences was to jump the perimeter fence and get a bit of turf which would then be in a bowl in the garden for ages.