Полная версия

The Front Runner

To his younger supporters, Hart was emblematic of the generational shift that was reshaping Americaâand not a moment too soon. The rebellious teens of the sixties were just now moving into middle age, with all the angst and self-absorption that had characterized their youth. (The second most popular sitcom in America, after The Cosby Show, was Family Ties, in which two former hippies struggled with their Reagan-loving teenage son, played by Michael J. Fox.) They had, in many ways, remade the popular culture already, creating an entirely new template for social justice through movies and TV, literature and music; Cosby himself was a transformational figure, drawing a huge number of white Americans into the story of the emerging black middle class. But when it came to political leadership, the Man still wasnât getting out of the way. By the dawn of 1987, President Reagan was seventy-five (and finally starting to look it), and his main Democratic foil, House speaker Tip OâNeill, was seventy-four. Reaganâs likely successor among Republicans, George H. W. Bush, was a comparatively sprightly sixty-two. Someone had to kick open the door to Washington and let the sixties generation come rushing through. And even before his thrilling run in 1984, Hart had been first in line.

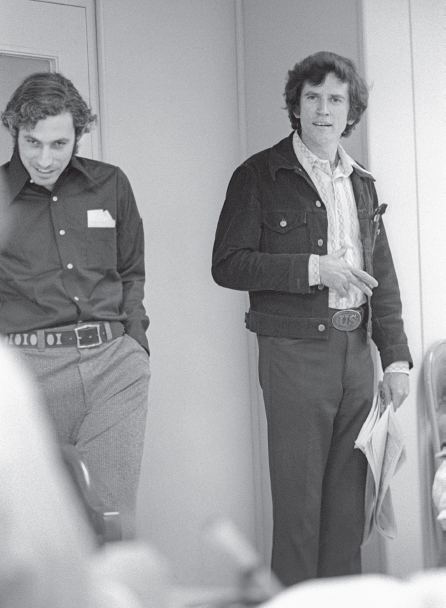

After all, wherever politicsâand Democratic politics specificallyâhad been headed in the two tumultuous decades before 1987, Hart had managed to lead the way. In 1969, when Hart was an unknown Denver lawyer with some ideas about reforming the electoral system, George McGovern picked him to serve on the commission that would institute the primary system for choosing Democratic nomineesâan innovation that transformed presidential politics almost immediately by taking power from the old urban bosses and handing it to a new generation of activists, including women and African Americans. A few years later, McGovern, seeking to take advantage of the new primary system, tapped Hart to assemble and run his improbable, antiwar presidential campaign. McGovern overturned the party establishment on his way to the nomination (and a crushing defeat in the general election), and Hart became famous as the young, brilliant operative in cowboy boots, straddling the motorcycle of his new pal, Hunter S. Thompson.

Gary Hart, at right, as Senator George McGovernâs campaign manager in the 1972 presidential election: thirty-five and a celebrity CREDIT: KEITH WESSEL

Hart got himself elected to the Senate just two years later, making him, at thirty-eight, its second youngest member. (Joe Biden, who got there in 1972, was six years younger.) Some older colleagues expected the glamorous ex-strategist to fashion himself as a left-wing revolutionary. But Hart was from the burgeoning West, where the partyâs Eastern orthodoxies were always viewed with some contempt, and he was, by nature, too inquisitive to follow the crowd. Instead, he made a name for himself by leading the emerging movement to modernize the Cold War military. (Among those who shared his passion was a young Georgia congressman by the name of Newt Gingrich, who joined Hartâs new âmilitary reform caucus.â) Hartâs foray into advances in modern weaponry led him, inevitably, to start thinking about the silicon chip and what it would mean for industry and education, too. Years later, Hart would remember an eye-opening lunch near Stanford with a couple of scruffy entrepreneurs named Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, who had recently set up a company called Apple in Jobsâs garage.

By the early eighties, having been reelected despite the Reagan tide that wiped out nine of his Democratic colleagues (including McGovern), Hart was the front man for a small group of younger, mostly Western lawmakers whom the media dubbed the âAtari Democrats.â Their main preoccupationâwhich few politicians of the time understood, much less talked aboutâwas how to transition the country and its military from the industrial economy to the computer-based world of the twenty-first century. This was dangerous ground for a Democrat in the 1980s, when industrial states and labor unions still threw around immense political power. Whenever anyone would ask Hart about whether his challenge to the status quo made him a liberal or a centrist, he would answer by drawing a simple graph on the back of a napkin or whatever else might be handy, sketching out a horizontal axis for notions of left and right, and then a vertical axis that represented the past and the future. Hart always placed himself in the upper left quadrantâprogressive, yes, but tilting strongly toward a new set of policies to match up with new realities.

This is precisely how Hart positioned himself in 1984, when his underfunded and undermanned campaign erupted in New Hampshire and swept the Westâas the young, forward-thinking alternative to his partyâs aging liberal establishment. âNot since the Beatles had stormed onto the stage of the Ed Sullivan Show twenty years before had any new face so quickly captivated the popular culture,â The Washington Postâs Paul Taylor later wrote of the 1984 campaign. âIndeed, the velocity of Hartâs rise in the polls was unprecedented in American political history.â Except that Hartâs youthful image belied what was, in retrospect, a critical distinction between the candidate and a lot of those who were assumed to be his contemporariesâthe activists, operatives, and reporters who represented the vanguard of the boomers. The baby boom had technically commenced in 1946. Hart, on the other hand, had been born a full decade earlier, in 1936. And those particular ten years happened to make a very big difference, temperamentally and philosophically, in the life of an American.

Those ten years meant that Hartâs essential worldview and personality were shaped more by his upbringing in the post-Depression Dust Bowl than by the beatniks or the social movements that later rocked Southern cities and college campuses. (Hart read about civil rights while doing his graduate studies in New Haven, but he never marched.) They meant that Hart, unlike his younger compatriots, didnât see the personal as the political; to him, the personal was the personal, and nobody elseâs business, and it wasnât polite to ask too many questions. His grandfather sat silently on his front porch all day with a Bible in hand, and nobody badgered him about it. (When a neighbor finally did dare to ask what exactly he was doing out there, the old man answered: âCramming for the finals.â) Though Hartâs father spent the war in Kansas, running through a succession of small businesses and houses, some of Hartâs uncles had returned from the Battle of the Bulge as hardened, silent men who drank too much and rode the rails for months at a time. They were his boyhood idols, and he knew better than to ask where theyâd been or what theyâd seen.

Like the role models of his youth, and like the taciturn railroad men he met during his first summers in Denver, where an uncle helped Hart land a job driving spikes in the ninety-degree heat, Hart learned to value reticence and privacy. And like his political heroes, the Kennedys, Hart believed that the political arena was constructed around recognized rules and boundaries, much like the societal rules and boundaries that had governed his upbringing.

This belief had only been reinforced by his experiences in public life. As a young senator (too young, really, to have merited such a prized assignment), Hart had served on the legendary Church Committee, which investigated the intelligence agenciesâ secret activities on American soil. The committee had uncovered the first tangible evidence of John Kennedyâs sexual escapades and even his connections to Mafia figures, none of which had ever been publicly reported, despite its obvious availability. From his days at the McGovern campaign, Hart knew all the big-time reporters in Washington well enough to drink with them late into the night, but in his experience what was said at the hotel bar always stayed at the hotel bar.

It was well known around Washington, or at least well accepted, that Hart liked women, and that not all the women he liked were his wife. After all, Gary and Lee Hart had fallen in love and married as kids, in the confines of a strict church where even dancing was prohibited. It wasnât just that Hart had never played the field before marriage; heâd never even stepped onto it. And so here he was, young and famous and sturdily good-looking, powerful in a city where power was everything, and friends knew that he and Leeâas so often happens with college sweetheartsâhad matured into different people, that she spent long periods back in Denver with the two kids, that she could drive him absolutely crazy at times. Twice he and Lee quietly agreed to separate for months at a time, and during one of those separations Hart had even moved in with his pal Bob Woodward and slept on the couchâat least when he wasnât gone for nights at a time. No one in Woodwardâs newsroom, or anyone else for that matter, ever thought to ask for details or to write a word about it. Why would they? Whose business was it, anyway?

A sense of remove from public life was crucial for Hart, and not simply, or even mostly, because of whatever women he was or wasnât spending the night with. You could see it in the way heâd walk into any room, maybe a Hollywood cocktail party or a Manhattan fundraiser, and immediately plant himself in a corner somewhere, or over by the fireplace, watching and waiting for others to approach, just as he had been impelled to do at the church mixers as a boy. Ideas and rhetorical flourishes came easily to him, but not celebrity. âI am an obscure man, and I intend to remain that way,â Hart told the writer Gail Sheehy during the 1984 campaign. Hart was an introvert who needed space to breathe and think and be alone, and he had risen through a political world where such a thing was not antithetical to success.

Once, during that first presidential campaign, when the presidency had suddenly and miraculously seemed within reach, Hart had sat down the lead agent on his Secret Service detail and quizzed him. What if Hart were president, and one day he wanted to fly off to, say, Boulder, and wander through the downtown by himself, talk to some voters, maybe buy a few books, and then hop back on the plane and return to Washington? Would the cameras need to follow? Would âRedwoodââthat was Hartâs Secret Service code nameâreally need the motorcade and the full detail and the rest of the traveling show? Yes, came the solemn replyâhe would need all of it. And it was hard for Hart to argue the point after the convention in San Francisco, when the agents had stopped the elevator of the St. Francis Hotel and hustled him back upstairs, because, it turned out, some kid with a loaded .22 in his backpack had been waiting outside. (Word came back from the Secret Service that the hapless gunman, apparently not much of a reader, hadnât gotten the word that Hart wasnât the nominee.)

Hart wrestled with this issue of privacy all the time, even after his friend Warren Beatty, who had come by such wisdom firsthand, told him flatly: âThere is no privacy.â Hart would say he felt called to the White House, in the way the Nazarenes spoke of a callingâcompelled to serve, in the way the Kennedys had been compelled. He wanted the job as badly as any man, and he believed, as any good candidate must, that he was singularly qualified to hold it. But he did worry about being miserable. More and more, as time went on, Hart wasnât content with the idea of simply becoming president. He meant to become president his way.

3

OUT THERE

IT STUNG BADLY, that moment in 1984 when Hartâs soaring campaign took a direct hit, when he started to lose altitude and never fully recovered. It was March, less than two weeks after his stunning, ten-point thrashing of Walter Mondale in New Hampshire, and the two men were seated next to each other during a televised debate at Atlantaâs Fox Theatre. A confident Hart was giving it to the former vice president pretty good, going on about the younger Americans who had entered the process in the previous decade, how weary they were of an aging Democratic establishment that cared only about keeping its interest groups happy, how badly they wanted new ideas. It was a theme that Hart had been sounding since 1973, when he wrote, in the closing pages of his memoir of the McGovern campaign, that âAmerican liberalism was near bankruptcy.â Despite President Kennedyâs poetry, Hart had written then, the torch wasnât passed from one generation to the nextâit had to be seized.

The fifty-six-year-old Mondale was no rookie, though, and he was ready with a canned one-liner that had been written for him by Bob Beckel, his sharp-tongued strategist (and later another cohost of Crossfire). The laconic former vice president had to wind up and start delivering the line several times, since he couldnât get Hart to shut up already and let him do it the way heâd practiced. âWhen I hear your new ideas,â Mondale finally said, in his flat Midwestern accent, âIâm reminded of that ad. âWhereâs the beef?ââ

Itâs probably hard for any American born after, say, 1980 to appreciate how devastating a line like that could be. This was before ubiquitous cable or DVRs or the phrase âaudience fragmentation.â Most American families watched one of the same three networks at the same time every night, so no one watching the debate at home could have missed what was then the most talked about advertising campaign in the countryâthat Wendyâs ad where one old woman kept talking about how big the bun was on the typical fast-food burger, while her tiny, white-haired companion blurted out: âWhereâs the beef?â Mondaleâs laugh line instantly became one of the seminal moments in the history of American debates. It recast him, instantly, as somehow more current and less of a cardboard cutout. And, more important, it underscored how little Democrats really knew about this young interloper who was on the verge of upending their party.

Hartâs 1984 campaign had been, from the start, something of an amateur enterprise; he had hovered around 3 percent in the polls for most of the campaign before New Hampshire. He hadnât yet figured out a facile way of communicating his worldview in a few sentences, and even if he had, his campaign lacked the funding and sophistication needed to get it across. Mondale had seen Hartâs vulnerability and struck at it. The blow didnât stop Hart from going on to win most of the remaining states, including California on the final day of voting before the convention. But Mondaleâs one great debate moment did arrest his precipitous slide long enough to keep the party regularsâand most notably the newly created âsuperdelegatesââin line, and it was they who ultimately ensured his path to the nomination.

There was never any question that Hart would run again, nor was there any question that he would be the presumed nominee, especially after his warnings about the partyâs dying establishment proved well founded. The first thing he did, the day after Reagan thoroughly humiliated Mondale at the polls that November by taking every state but Mondaleâs native Minnesota, was to call Bill Dixon, Wisconsinâs banking commissioner and his old friend from McGovern days, and ask him to come to Washington. The plan was for Dixon, a Wisconsin lawyer who had worked on several presidential campaigns and run the 1980 convention for Jimmy Carter, to run Hartâs Senate office until his second term expired at the end of 1986. Then Hart would retire from the Senate to focus his energy on running, and Dixon would be charged with doing what he was really there to do in the first place, which was to build a truly top-flight presidential campaign for 1988, the kind that couldnât be so easily caricatured by well-paid consultants with a single well-placed zinger.

âWhereâs the beef?â: Hart and Mondale share a laugh before the 1984 campaign. Mondale would use the phrase to devastating effect. CREDIT: KEITH WESSEL

In the more than thirty years since the ratification of the Twenty-second Amendment, which limited the president to two full terms in office, neither party had yet managed to win a third consecutive election, as Republicans would need to do in order to deny Hart the White House. Everyone agreed: it was Hartâs race to lose. And he was going to have the campaign he needed in order to beat the sitting vice president, George H. W. Bush, and end the Reagan era once and for all.

By the time 1986 rolled around, though, Hart was deeply ambivalent about his new status as the partyâs leading man. In part, his concerns were temperamental. For the first time in his political life, going back to the 1960s, Hart was now the Man, rather than the insurgent, and the role was unfamiliar and uncomfortable for him. No one had ever accused him of telling ward leaders or union bosses what they wanted to hear, or of cozying up to other powerful interests; if anything, he leaned too hard toward the opposite approach. But now that he was assumed to be the nominee, everybody wanted a sit-down meeting or a quick grip-and-greet, some commitment to protect steel jobs or oppose nukes or whatever. Now all the influential organizers and fundraisers in the early primary states, the guys who had shunned him last time around, were looking for a lunch with the candidate and a photo with the kids. Like so many other Americans whose self-image was grounded in the sixties, Hart in his middle age found himself struggling not to become the very thing he had once disdained.

And it wasnât simply the mechanics of the thing, this process of whoring himself out like any other cheap politician, that seemed untenable. It was also the idea that if he ran for president like a front-runner, he wouldnât actually be able to be president, or at least not in the way he intended. From the early 1980s, Hart had been thinking at least as much about how he would govern as how he would get elected. For example, his chief foreign policy aide, Doug Wilson, had set up something called the âNew Leadersâ program, which was essentially an annual meeting of up-and-coming politicos from countries around the world; Hartâs idea was that a president should come into office with a network of highly placed friends in other governments, rather than investing the first two years of a presidency in getting to know them. Hart saw himself as a transformational figure who would free the country from the stifling, left-right orthodoxies of the Cold War era. If he campaigned as the vehicle of everyone who wanted to protect the partyâs status quo, he complained, then he wouldnât be able to claim the public mandate he needed to govern like a reformer.

Then there was the tactical problem inherent in being the front-runner. Alone among major candidates of the modern era, Hart had, by that time, experienced presidential campaigns as both a lead strategist and as a candidate. So however much Hart may have liked to project an image of rising above the mediaâs game of electoral chess, in truth he was already thinking several moves beyond his younger advisors. Having played a fundamental role in creating the modern primary system, Hart had now seen two long-shot candidatesâMcGovern and Carterâuse it to shock better-known and better-funded opponents, and he himself had come impossibly close to doing the same thing in 1984. So no one understood better than Hart that the most perilous place to be in Democratic politics in the post-reform era was at the pinnacle of the primary field, as the anointed candidate of the establishment. Hart felt sure that if he were to embrace his role as the presumed nominee, he would become as vulnerable in â88 as Mondale had been in â84.

It didnât help that the emerging group of candidates who hoped to exploit Hartâs vulnerability as the obvious front-runner lookedâto use the term privately employed by Hartâs campaign staffâlike a bunch of ânew Garys.â In 1984, Hartâs chief advantage had been his relative youth, the way in which he marked the arrival of the sixties generation. What his success had done, though, was to clear the path for a new group of his contemporaries, who were already testing their own presidential ambitionsâWashington prodigies like Joe Biden and Al Gore in the Senate and Dick Gephardt in the House. (A little known Southern governor named Bill Clinton, whom Hart had once hired to work on the McGovern campaign, was also said to be exploring a run, although he would ultimately demur.)

Suddenly, these guys, too, were touting their comparative youth and rejecting the liberal orthodoxies of the postwar generation, embracing military reform and the potential of high-tech industries in Hart-like fashion. Known throughout his career as a reformer, Hart, who would be fifty by the time he announced his candidacy, now faced the danger of becoming another establishment retread.

The extent to which Hart was wrestling with this questionâhow to be the partyâs recognized front-runner without forfeiting his credentials as an antiestablishment Democratâis evident from a memo he wrote sometime in 1986. At Hartâs request, two of his most trusted aides, Billy Shore and Jeremy Rosner, had written their boss a secret memo laying out an overarching strategy for securing the nomination and then the White House in 1988. That memo is lost to the ages, but Hartâs point-by-point response, written in longhand and all capital letters on a legal pad, offers a fascinating window into the political calculations he was trying to makeâand into the depth of his personal involvement in campaign strategy. In the first of his twenty-seven âcomments and critiques,â Hart wrote: âI am not an âoutsiderâ out to defeat the party establishment. I am independent from the establishment, uniquely positioned to re-position it and move it forward (c.f. FDR, JFK).â In other words, he intended to make the convoluted argument that he was inside the establishment, but not of it.

âI have a strong regional base (west) and demographic base (young),â Hart wrote. âPlus my greatest strength as a Democrat is among independents. We must get analysts to understand that. I can broaden the partyâs base.â He made it clear that he had no intention of retooling his own political argument. âI do not need to distinguish myself from the ânew Garysââthey have to distinguish themselves from me,â he wrote. âIn every case it will make their nomination less likely. Letâs not go on the defensive!â

In fact, Hart intended to be very much on the offensive, and he had in mind his own strategy for putting some distance between himself and the Democratic establishment, while simultaneously making all the new Garys seem small and conventional. The big idea was to focus almost exclusively on big ideas, rather than on the usual political machinations. To start with, over three days in June 1986, Hart gave a series of three foreign policy lectures at Georgetown University, in which he outlined, with unusual technicality, the new approach he called âEnlightened Engagement.â Essentially, Hart argued that in the world after the Cold War, where nations would inevitably rise up to determine their own futures, the United States would no longer be able to protect its interests by deploying missiles and propping up repressive states; now it would need to retool its military to respond to stateless threats, and it would have to nurture democratic movements, mainly through economic assistance.

Twenty-five years later, that all sounds pretty routine. But in the context of 1986, especially for a Democrat, it was both provocative and prescient. Among those who bristled at Hartâs pragmatic vision was his old mentor George McGovern, whom Hart asked to preview the lectures. In a private letter to Hart written in May 1986, the dovish McGovern, echoing other liberals, listed his âreservationsâ about Hartâs worldview, most notably that he thought Hart overstated Soviet aggression and was too harsh toward Nicaraguaâs Communist government. McGovern also objected to a proposal to expand NATOâs conventional forces in the waning years of the Cold War, in order to ease Europeâs reliance on Americaâs nuclear arsenal. âIs the concept of mutual force reductions dead?â he despaired.