Полная версия

National Geographic Kids Chapters: The Whale Who Won Hearts: And More True Stories of Adventures with Animals

Copyright © 2014 National Geographic Society

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Published by the National Geographic Society

John M. Fahey, Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer

Declan Moore, Executive Vice President; President, Publishing and Travel

Melina Gerosa Bellows, Publisher and Chief Creative Officer, Books, Kids, and Family

Prepared by the Book Division

Hector Sierra, Senior Vice President and General Manager

Nancy Laties Feresten, Senior Vice President, Kids Publishing and Media

Jennifer Emmett, Vice President, Editorial Director, Kids Books

Eva Absher-Schantz, Design Director, Kids Publishing and Media

Jay Sumner, Director of Photography, Kids Publishing

R. Gary Colbert, Production Director

Jennifer A. Thornton, Director of Managing Editorial

Staff for This Book

Becky Baines, Shelby Alinsky, Project Editors

Marfé Ferguson Delano, Editor

Kelley Miller, Senior Photo Editor

Amanda Larsen, Art Director

Ruth Ann Thompson, Designer

Ariane Szu-Tu, Editorial Assistant

Callie Broaddus, Design Production Assistant

Margaret Leist, Illustrations Assistant

Grace Hill, Associate Managing Editor

Joan Gossett, Production Editor

Lewis R. Bassford, Production Manager

Susan Borke, Legal and Business Affairs

Production Services

Phillip L. Schlosser, Senior Vice President

Chris Brown, Vice President, NG Book Manufacturing

George Bounelis, Senior Production Manager

Nicole Elliott, Director of Production

Rachel Faulise, Manager

Robert L. Barr, Manager

For more information, please visit

www.nationalgeographic.com, call 1-800-NGS LINE (647-5463), or write to the following address:

National Geographic Society, 1145 17th Street

N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at

www.nationalgeographic.com/books

For librarians and teachers:

www.ngchildrensbooks.org

National Geographic supports K–12 educators with ELA Common Core Resources. Visit natgeoed.org/commoncore for more information.

More for kids from National Geographic:

kids.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org

Trade paperback ISBN:

978-1-4263-1520-6

Reinforced library edition ISBN:

978-1-4263-1521-3

eBook ISBN: 978-1-4263-1606-7

v3.1

Version: 2017-07-10

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

QUEST FOR LIVING DINOSAURS

Chapter 1: A Shot in the Dark

Chapter 2: Trapped in a Net!

Chapter 3: Into the Wild!

THE ICE, THE SEALS, AND ME

Chapter 1: The Whitecoats Arrive

Chapter 2: Deadly Ice

Chapter 3: Sink or Swim!

THE WHALE WHO WON HEARTS

Chapter 1: A New Friend!

Chapter 2: A Whale Named Wilma

Chapter 3: A Dream Come True

THE REEF WHERE SHARKS RULE

Chapter 1: Hooked on Sharks

Chapter 2: Fish Bites!

Chapter 3: Stranded!

Sneak Preview of Lucky Leopards

More Information

Dedication

Credits

Acknowledgments

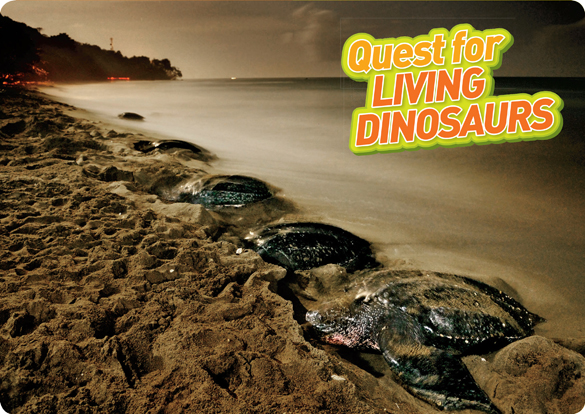

Five female leatherback sea turtles scoot up onto the beach to lay their eggs.

This is me, photographer Brian Skerry, with my special underwater camera and lights. I’m getting ready to dive.

It was a warm night in May. I was walking along a beach in Trinidad (sounds like TRIH-nuh-dad), an island in the Caribbean (sounds like CARE-uh-BEE-un) Sea. It was almost midnight. The ocean waves rumbled and crashed onto the sand. Behind the beach, palm trees swayed in the damp breeze.

Suddenly, a few yards down, I spotted dark shapes on the sand.

Did You Know?

The temperature inside a leatherback’s nest determines if the baby turtles will be male or female.

They looked like huge rocks. But they were leatherback sea turtles! They were here to do something sea turtles have been doing for more than 100 million years. And I was hoping to shoot them. With my camera, that is!

My name is Brian Skerry. I’m an underwater wildlife photographer. It’s my job to take pictures of animals that live in the sea.

I fell in love with the sea when I was a child. I grew up in a small town in Massachusetts. We lived about an hour’s drive from the ocean. I was always asking my parents to take me there.

When I wasn’t at the beach, I was reading books or watching TV shows about ocean life. I really admired the sea turtles. It was fun to imagine gliding with them through miles of deep, blue water.

When I was 15, I tried scuba diving. It was in my family’s swimming pool. I was sitting in the shallow end. I had the scuba tank on my back. Hoses attached to the tank would bring air to my mouthpiece. I’ll never forget putting that mouthpiece in and taking my first breath underwater. All I could think was, “Wow! I have discovered a whole new world!”

As I grew up, I practiced diving. I studied photography in college. I began taking underwater photos. Finally, I landed my dream job. I was hired to take photos for National Geographic magazine. And that’s what brought me to Trinidad. I was there to photograph sea turtles for National Geographic.

Sea turtles are reptiles. Like all reptiles, they breathe air. But unlike most reptiles, sea turtles don’t live on land. They spend nearly their entire lives in the ocean. That’s why they’re called marine reptiles.

One hundred million years ago, dinosaurs ruled the land. At that time, many types of marine reptiles lived in the oceans. Giant, long-necked plesiosaurs (sounds like PLEEZ-ee-oh-soars) and sharp-toothed ichthyosaurs (sounds like ICK-thee-oh-soars) swam the seas. Earth’s first sea turtles swam with them.

Dinosaurs died out 65 million years ago. Marine reptiles went extinct then, too—all of them except for sea turtles, that is.

Seven types of sea turtles are still around today. The leatherback is the largest of them all. Leatherbacks can grow to more than seven feet (2 m) long. They can weigh more than 2,000 pounds (900 kg).

Other types of sea turtles have hard shells. Not leatherback sea turtles. They have thick, leathery skin. It’s what gives them their name.

My assistant Mauricio (sounds like moh-REE-cee-oh) Handler was with me on the beach. As we watched, the giant female leatherbacks began to dig their nests and lay their eggs. Female leatherbacks always lay their eggs on warm, sandy beaches. Usually they return to the same beach where they were born.

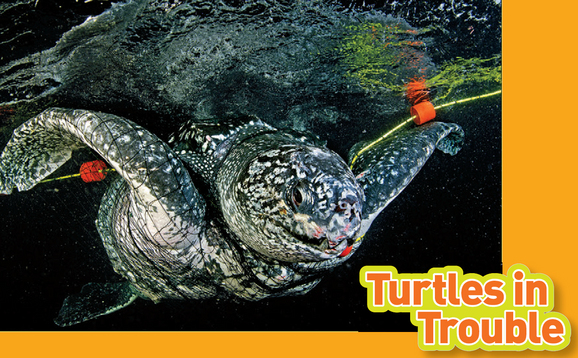

Sadly, leatherback turtles are in danger of extinction. People have been hunting leatherbacks for centuries. But over the past 30 years, too many have been killed for their meat. People raided nests and took all the eggs. Today, new laws help protect nesting leatherbacks and their eggs. But they still face many dangers. They get tangled in fishnets. They get hooked on longlines meant to catch large fish. Houses and hotels have also been built on some of the leatherbacks’ favorite nesting beaches.

I moved in close to one of the turtles. Leatherbacks only come out when it is dark. I knew the camera flashbulb would disturb her. So I would rely on the moonlight.

The turtle found a spot she liked. She made a shallow pit in the sand with her front flippers. Once she was comfy, she dug a deep hole with her hind flippers. She took long, deep breaths as she dug. To me, it was like a sound from the prehistoric (sounds like pre-hih-STORE-ick) past! She laid more than 80 round, white eggs in the hole. Then she covered them with sand.

We watched as the turtle headed back to the water. Having a chance to photograph this huge creature in the wild was thrilling—almost like seeing a living dinosaur!

A newly hatched baby leatherback scurries to the sea. It will spend the rest of its life in the water.

It takes 60 to 70 days for a leatherback’s babies to come out of their eggs. While we were taking photos of the nesting leatherbacks, eggs from other nests began to hatch. We stopped to take photos as the tiny, striped hatchlings hurried across the sand. Their mothers were long gone. Leatherback babies must look to the sea for food and protection.

Did You Know?

Leatherbacks can dive as deep as 4,000 feet (1,219 m). Even the most skilled human scuba divers cannot dive much deeper than 1,000 feet (305 m).

For the lucky few who make it to adulthood, there aren’t many ocean creatures that can harm them. But humans have created new problems for these ancient (sounds like ANE-chunt) animals. I wanted to see for myself the dangers leatherbacks face once they leave the shore. It was time to get into the water!

I talked to local fishermen and found one who was interested in helping. He said leatherbacks sometimes got tangled in his fishnets. He did what he could to save them. But sometimes he was too late. If a tangled turtle is not pulled to the surface soon enough, it will drown.

The fisherman said we could follow him while he fished. If any turtles got caught, we could see how it happened. Maybe we could even help. We rented a small boat. The captain of our boat helped us sail close behind the fishing boat.

We watched as the fisherman set out a mile (1.6 km) of fishnet. Floats held up the top edge of the net. The rest of it hung down in the water, like a curtain. After several hours, the fisherman pulled in his net. Dozens of fish were caught in it. He put the fish in his boat. Then he set the net out again.

Our captain moved our boat slowly alongside the net. I sat in the front of the boat. The stars shone brightly above us. I kept an eye on the net below. I had my fins, mask, and air tank ready, in case I needed to dive.

Later that night, Mauricio and I spotted an adult turtle in the net. I quickly pulled on my diving gear and went over the side. As I swam down, I could see the leatherback struggling.

Leatherbacks never stop swimming. The turtle paddled and paddled with its long flippers. The more it paddled, the more tangled it became. I took a few pictures of it. Then I had to help it. I grabbed my knife and began to cut the net.

As I worked, the current began to wrap me up in the net, too. I had to stop helping the turtle and cut myself free first. Then I cut the turtle loose. I watched as it swam off gracefully, into the darkness of the sea.

Jellyfish, or jellies, are a leatherback’s favorite food. Jellies are mostly water, with a few minerals and a dash of protein thrown in. How do leatherbacks grow so big on a jelly diet? The answer: they eat a LOT of jellies. Scientists videotaped one leatherback eating 69 jellies in three hours. Each jelly weighed about ten pounds (4.5 kg). That’s 690 pounds (313 kg) of jellies! A leatherback’s throat is lined with three-inch (7.6-cm) spines. These spines help the turtle swallow its very slippery prey—and keep the prey from coming back up.

I found this leatherback swimming in deep water. The two yellow fish clinging to her side are called remoras.

Now I had pictures of a leatherback underwater. But I wanted to take photos of one swimming. I knew I’d find turtles swimming around Trinidad. But the water there is too murky to get good photos. I needed to find leatherbacks in clear water. So I went to the other side of the world. To the Pacific Ocean!

I headed for one of the turtles’ favorite hunting grounds. It is in the deep water off the Kai (sounds like KEY) Islands in Indonesia (sounds like in-doh-NEE-zhuh).

My assistant Jeff Wildermuth joined me on this trip. When we got to the Kai Islands, we talked to some local fishermen. They gave us tips on how to find turtles.

The fishermen go out to sea in long, narrow boats. Boats like this have been used in these islands for thousands of years. I decided to use one of them to search for leatherbacks. I knew it could be dangerous. The boats are very tippy when the waves get steep! But this was my best bet for getting close to the turtles.

The local people told us they often found turtles around a certain island. Jeff and I set up our tents on the beach there. Then we decided to try our luck.

Jeff and I eased our boat off the sand and into the choppy water. We watched for the glint of a black turtle moving under the silvery waves. Meanwhile, the sun blazed down on us. We gulped water from our water bottles. We paddled around the whole island, searching. Before we knew it, the sun was going down. We hadn’t seen one turtle.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.