Полная версия

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

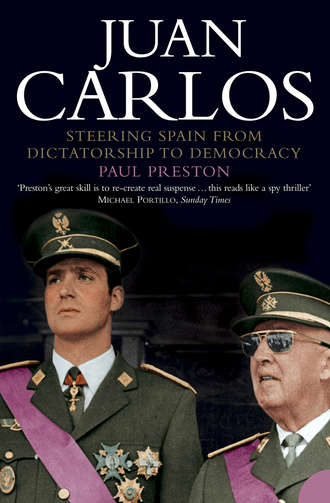

The confidence in himself and his office generated by such ceremonial was revealed when Franco celebrated the first year of his Movimiento. His broadcast speech was, according to his cousin, entirely written by himself. He spoke in terms which suggested that he placed himself far higher than the Borbón family, as a providential figure, the very embodiment of the spirit of traditional Spain. He attributed to himself the honour of having saved ‘Imperial Spain which fathered nations and gave laws to the world’.26 On the same day, an interview with the Caudillo was published in the monarchist newspaper ABC. In it, he announced the imminent formation of his first government. Asked if his references to the historic greatness of Spain implied a monarchical restoration, he replied truthfully while managing to give the impression that this was his intention, ‘On this subject, my preferences are long since known, but now we can think only of winning the War, then it will be necessary to clean up after it, then construct the State on firm bases. While all this is happening, I cannot be an interim power.’

For Franco, and indeed many of his supporters within the Nationalist zone, the monarchy of Alfonso XIII was irrevocably stigmatized by its association with the constitutional parliamentary system. In his interview, he declared that, ‘If the monarchy were to be one day restored in Spain, it would have to be very different from the monarchy abolished in 1931 both in its content and, though it may grieve many of us, even in the person who incarnates it.’ This was profoundly humiliating for Alfonso XIII, all the more so coming from a man whose career he had promoted so assiduously.27

The Caudillo’s attitude to the exiled King, and by implication, to the Borbón family, was underlined in a harshly dismissive letter sent to Alfonso XIII on 4 December 1937. The King, having recently donated one million pesetas to the Nationalist cause, had written to Franco expressing his concern that the restoration of the monarchy seemed to be low on his list of priorities. The Generalísimo replied coldly, insinuating that the problems which caused the Civil War were of the King’s making and outlining both the achievements of the Nationalists and the tasks remaining to be carried out after the War. Expanding on his ABC interview, the Caudillo made it clear that Alfonso XIII could expect to play no part in that future: ‘the new Spain which we are forging has so little in common with the liberal and constitutional Spain over which you ruled that your training and old-fashioned political practices necessarily provoke the anxieties and resentments of Spaniards.’ The letter ended with a request that the King look to the preparation of his heir, ‘whose goal we can sense but which is so distant that we cannot make it out yet’.28 It was the clearest indication yet that Franco had no intention of ever relinquishing power, yet the epistolary relationship between Franco and the exiled King remained surprisingly smooth. (Indeed, in December 1938, Franco revoked the Republican edict that had deprived the King of his Spanish citizenship and the royal family of its properties.) Throughout the Civil War, after each victory, the Generalísimo had sent a telegram to Alfonso XIII and, in turn, received congratulatory messages from both the exiled King and his son. However, after the final victory, and the capture of Madrid, Franco had not done so. The outraged Alfonso XIII rightly took this to mean that Franco had no intention of restoring the monarchy.29

If the future of Alfonso XIII’s heir was unclear to Franco, even less certain was that of his grandson, Juan Carlos. For the first four and a half years of his life, the boy lived with his parents in Rome. Soon after his birth the family moved from the modest flat on the top floor of the Palazzo Torlonia in Via Bocca di Leoni to the four-storey Villa Gloria, at 112 Viale dei Parioli in the elegant Roman suburb of Parioli.30 This was a happy time for the Borbóns – a period during which it was possible to live as a relatively normal, as opposed to a royal, family. Juan Carlos’s younger sister Margarita was born blind on 6 March 1939. Even so, the degree of family warmth was limited. All three children were looked after by two Swiss nannies, Mademoiselles Modou and Any, under the supervision, not of their mother but of the Vizcondesa de Rocamora. The young Prince was often taken out for walks by his parents or by his nannies, sometimes to the Palazzo Torlonia, sometimes to the private park of the Pamphili family or to the park of Villa Borghese. Don Juan showed some affection for his eldest son, often carrying him in his arms when they visited Alfonso XIII at the Gran Hotel.

However, such signs of warmth were rare. The young Prince was soon being schooled in the harsh lesson that his central purpose in life was to contribute in some way to the mission of seeing the Borbón family back on the throne in Spain. Don Juan had already started to make demands that the child found difficult to meet. Miguel Sánchez del Castillo (a film actor working in Rome at the time) recalls that, on one occasion, Juan Carlos was given a cavalry uniform as a present from several Spanish aristocratic ladies. ‘An Italian photographer spent over an hour taking pictures of him. Don Juan Carlos, who was only four years old at the time, endured having to stand to attention on a table. When they finally took him to the kitchen and one of his nannies took his boots off, his feet had been rubbed raw, because the boots were too small for him. That is when he shyly started to cry. I later learnt that his father had taught him from a very young age that a Borbón cries only in his bed.31

Two events soon disturbed the royal family’s tranquillity: the first was Queen Victoria Eugenia’s departure from Rome; the second was Alfonso XIII’s death. Victoria Eugenia had been spending increasing amounts of time in Rome. When Italy entered the Second World War on 9 June 1940, her position as an English woman became difficult and thereafter she divided her time between Lausanne in neutral Switzerland and the outskirts of Rome. She and her husband had been effectively separated for more than a decade but, as his health deteriorated, they spent more time together. In 1941, she returned to Rome in order to care for him, moving into the nearby Hotel Excelsior, where she stayed until his death.32

Alfonso XIII died on 28 February 1941. A few weeks earlier, on 15 January, he had abdicated in favour of his son and heir, Don Juan. Speaking with the American journalist, John T. Whitaker, shortly before his end, the exiled King said, ‘I picked Franco out when he was a nobody. He has double-crossed and deceived me at every turn.’33 Alfonso was right. During his final agony, he kept asking whether Franco had enquired about his health. Pained by his desperate insistence, his family lied and told him that the Generalísimo had indeed sent a telegram asking for news. In reality, Franco showed not the slightest concern. At Alfonso XIII’s bedside, Don Juan made a solemn promise to his father to ensure that he was buried in the Pantheon of Kings at El Escorial. His promise could not be fulfilled while Franco remained alive, and Alfonso XIII’s body would remain in Rome until its transfer to El Escorial in early 1981. Franco was reluctant even to announce a period of national mourning for the King. He grudgingly agreed to do so only when faced with the sudden appearance of black hangings draped from balconies in the streets of Madrid. He limited himself to sending a red and gold wreath. Amongst the many other floral tributes that adorned Alfonso XIII’s funeral on 3 March 1941 was one from Juan Carlos. It was a simple arrangement of white, yellow and red flowers tied together with a black ribbon on which someone had sewn with a yellow thread the dedication ‘para el abuelito’ (for granddad).34

The death of Alfonso XIII seemed, in all kinds of ways, to free Franco to give rein his own monarchical pretensions. He insisted on the right to name bishops, on the royal march being played every time his wife arrived at any official ceremony and planned, until dissuaded by his brother-in-law, to establish his residence in the massive royal palace, the Palacio de Oriente in Madrid. By the Law of the Headship of State published on 8 August 1939, Franco had assumed ‘the supreme power to issue laws of a general nature’, and to issue specific decrees and laws without discussing them first with the cabinet ‘when reasons of urgency so advise’. According to the sycophants of his controlled press, the ‘supreme chief was simply assuming the powers necessary to allow him to fulfil his historic destiny of national reconstruction. It was power of a kind previously enjoyed only by the kings of medieval Spain.35

The 27-year-old Don Juan – now, in the eyes of many Spanish monarchists, King Juan III – took the title of Conde de Barcelona, the prerogative of the King of Spain. He faced a lifelong power struggle with Franco, who held virtually all the cards. For the task of hastening a monarchical restoration, he could rely only on the support of a few senior Army officers. However, the Falange was fiercely opposed to the return of the monarchy and Franco himself had no intention of relinquishing absolute power. In the aftermath of the Civil War, many conservatives who might have been expected to support Don Juan were reluctant to face the risks involved in getting rid of Franco. Accordingly, Don Juan began to seek foreign support. With an English mother and service in the Royal Navy, his every inclination was to look to Britain. But he was resident in Fascist Italy and the Third Reich was striding effortlessly from triumph to triumph. Accordingly, his close adviser, the portly and foul-mouthed Pedro Sainz Rodríguez, pressed him to seek the support of Berlin or at least secure its benevolent neutrality towards a monarchical restoration in Spain.36 On 16 April 1941, Ribbentrop instructed the German Ambassador in Spain, Eberhard von Stohrer, to inform Franco – lest he hear of it through other channels – that Don Juan de Borbón had tried to contact the Germans through an intermediary in order to get their support for a monarchist restoration. The intermediary had approached a German journalist, Dr Karl Megerle, on 7 April and again on 11 April 1941. In the early summer of 1941, the Italian Ambassador in Spain, Francesco Lequio, recounted rumours circulating in Madrid that Don Juan was about to be invited to Berlin to discuss a restoration. Lequio reported that the intensification of efforts to accelerate the restoration were emanating from Don Juan’s mother – ‘an intriguer, eaten up with ambition’.37

In response to the approaches made to the Germans by Don Juan’s supporters, Franco wrote an impenetrably convoluted letter to him at the end of September 1941. The tone was deeply patronizing: ‘I deeply regret that distance denies me the satisfaction of being able to enlighten you as to the real situation of our fatherland.’ The gist was a tendentious summary of Spain’s recent history which permitted Franco to combine the apparently conciliatory gesture of recognizing Don Juan’s claim to the throne with the threat that he would play no part in the future of the regime if he did not refrain from pushing that claim. What was quite clear was Franco’s total identification with the cause of the Third Reich – unmistakably referring to Britain and Russia when he spoke of ‘those who were our enemies during the Civil War … the nations who yesterday gambled against us and today fight against Europe’. Warning Don Juan against any action that might diminish Spanish unity (that is to say, threaten the stability of Franco’s position), he underlined the need ‘to uproot the causes that produced the progressive destabilization of Spain’ – a sly reference to the mistakes of the reign of Alfonso XIII. This task could be fulfilled only by his single party, the great amalgam known as the Movimiento, which was dominated by Falangists. Don Juan was warned that only by refraining from rocking Franco’s boat might he, ‘one day’, be called to crown Franco’s work with the installation – not restoration – of Spain’s traditional form of government.38

Don Juan waited three weeks before replying. The delay may have been caused by the fact that, on 3 October 1941, his second son had been born. Christened Alfonso after his recently deceased grandfather, he would soon be the apple of his father’s eye. When he did write to the Caudillo, Don Juan seized on the recognition of his claim to the throne and suggested that Franco convert his regime into a regency as a stepping stone to the restoration of the monarchy.39 Subsequently, knowing that Franco was in no hurry to bring back the monarchy, and as part of their ongoing power struggle with the Falange, a group of senior Spanish generals sent a message to Field-Marshal Göring in the first weeks of 1942. They requested his help in placing Don Juan upon the throne in Madrid in exchange for an undertaking that Spain would maintain its pro-Axis policy. Pressure on Franco was stepped up in the early spring, when, at the invitation of the Italian Foreign Minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, Don Juan attended a hunting party in Albania where he was received with sumptuous hospitality and full honours by the Italian authorities. In May, it was rumoured in Madrid that Göring himself had met with Don Juan in Lausanne (where he and his family were now resident) to express his support for his ambitions. Johannes Bernhardt, Göring’s unofficial representative in Spain, arranged at the end of May for General Juan Vigón to be invited to Berlin to discuss the matter. Vigón was both Minister of Aviation and one of Don Juan’s representatives in Spain. At the same time, Franco’s Foreign Minister, Ramón Serrano Suñer, had come to favour a monarchical restoration in the person of Don Juan. In June 1942, Serrano Suñer told Ciano in Rome that he believed that the Axis powers should come out in favour of Don Juan in order to neutralize British support for him. Serrano Suñer was planning to visit Don Juan in Lausanne. A somewhat alarmed Franco prohibited the trips of Vigón and of Serrano Suñer.40

In fact, the brief flirtation between some monarchists and the Axis soon came to an end. It was clear that the fate of the monarchy would be better served by alignment with the British. Soon after her husband’s death, Victoria Eugenia had returned to her home in Lausanne, La Vieille Fontaine. In the summer of 1942, Don Juan moved his family there too and, shortly afterwards, appointed the four-year-old Juan Carlos’s first tutor. His strange choice was the gaunt and austere Eugenio Vegas Latapié, an ultra-conservative intellectual. In 1931, appalled by the establishment of the Second Republic, Vegas Latapié, for whom democracy was tantamount to Bolshevism, had been the leading light of a group which set out to found a ‘school of modern counter-revolutionary thought’. This took the form of the extreme rightist group, Acción Española, whose journal provided the theoretical justification for violence against the Republic, while its well-appointed headquarters in Madrid served as a conspiratorial centre.41 Shortly after the creation of Acción Española, Eugenio Vegas Latapié had written to Don Juan and a friendship had been forged. Ironically, Vegas Latapié had helped elaborate the idea that the old constitutional monarchy was corrupt and had to be replaced by a new kind of dynamic military kingship, a notion used by Franco to justify his endless delays in restoring the Borbón monarchy. Now, as a faithful servant of Don Juan, his outrage at this was such that, despite having served in the Nationalist forces during the Civil War, he turned against Franco. In April 1942, Don Juan asked Vegas Latapié to join a secret committee with the task of preparing for the restoration of the monarchy. When Franco found out, he ordered both Vegas Latapié and Sainz Rodríguez exiled to the Canary Islands. Sainz Rodríguez took up residence in Portugal and Vegas Latapié fled to Switzerland where he became Don Juan’s political secretary.

Deeply reactionary and authoritarian, Vegas Latapié had a powerfully sharp intelligence but seemed hardly suitable to be mentor to a four-year-old child, particularly one who was far from intellectually precocious. Inevitably, Vegas Latapié’s nomination as the boy’s tutor did little for the rather introverted Juan Carlos. Neither his tutor nor his father took much notice of him, their attention being absorbed by the progress of the War and plans for the return of Don Juan to the throne. Initially, Vegas Latapié’s role was, at Don Juan’s request, to give Spanish classes to Juan Carlos because the boy spoke the language with some difficulty, having a French accent and using many Gallicisms. When Juan Carlos reached the age of five, he began to attend classes at the Rolle School, in Lausanne. Vegas Latapié would accompany him to school in the morning and pick him up in the afternoon, using the trip to give the boy his extremely partisan and reactionary view of Spain’s past.42

The relationship between Don Juan and Franco was developing in such a way as to dictate the direction of the young Prince’s later childhood, his adolescence and his adulthood. Fearful that the approaches made to the Germans by Don Juan’s supporters might bear fruit, on 12 May 1942, Franco had written him another patronizing letter based on his bizarre interpretation of Spanish history. In it, he rejected the notion that there was support in Spain for a restoration and reiterated his rejection of everything associated with the constitutional monarchy that fell in 1931. Linking the greatness of imperial Spain with modern Fascism, he stated that the only monarchy that could be permitted was a totalitarian one such as he associated with Queen Isabella I of Castile. He made it clear that there would be no restoration in the near future, and none at all unless the Pretender were to express his commitment to the Spanish single party, FET y de las JONS (Falange Española Traditionalist a y de las juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista), created in 1937 by the forced unification of all right-wing parties.43

Don Juan did not reply to Franco’s letter of May 1942 for ten months. The outbreak of violent clashes between monarchists and Falangists – and the consequent removal of Ramón Serrano Suñer – in mid-August 1942 boosted his confidence. The Allied landings in North Africa on 8 November 1942 convinced him that the best chance of a restoration was to distance himself from Franco and persuade the Allies that, after the War, the monarchy could provide both stability and national reconciliation. On 11 November 1942, barely three days after the landings, Don Juan’s most powerful supporter, General Alfredo Kindelán, the most senior general on active service and Captain-General of Catalonia, travelled to Madrid. After discussing recent events with the rest of the high command, Kindelán informed the Caudillo in unequivocal terms that if he had committed Spain formally to the Axis then he would have to be replaced as Head of State. In any case, he advised Franco to proclaim Spain a monarchy and declare himself regent. Franco swallowed his fury and responded in a conciliatory – and deceitful – way. He denied any formal commitment to the Axis, implied that he was anxious to relinquish power and confided that he wanted Don Juan to be his ultimate successor. Franco was seething. After a cautious interval of three months, he replaced Kindelán as Captain-General of Catalonia.44

When Don Juan did finally reply to Franco’s letter, in March 1943, his tone was altogether more confrontational than before. He questioned Franco’s exercise of absolute power without institutional or juridical basis and expressed alarm at both the continued divisions within Spain and the international situation. He firmly informed Franco that it was his patriotic duty to: ‘abandon the current transitory and one-man regime in order to establish once and for all the system which, according to Your Excellency’s oft-repeated phrase, forged the greatness of our fatherland’. He bluntly stated that he found entirely unacceptable Franco’s vague formula of delaying the return of the monarchy until his work was done. Then, in terms that can only have horrified Franco, Don Juan roundly rejected the Caudillo’s call for him to identify with the Falange, asserting that any link with a specific ideology ‘would mean the outright denial of the very essence of the value of monarchy which is radically opposed to the provocation of partisan divisions and domination by political cliques and is rather the highest expression of the interests of the entire nation and the supreme arbiter of the antagonistic tensions inevitable in any society’.

In his letter, Don Juan outlined the formula for the eventual restoration of a democratic monarchy in Spain on the basis of national reconciliation – although he cannot have imagined that it would take a further 32 years. Recalling Alfonso XIII’s declaration in 1931 that he was ‘Rey de todos los españoles’ (King of all Spaniards), Don Juan presented Franco with a slap in the face for which he would never be forgiven: ‘In fact, my arrival on the throne after a cruel civil war should, in contrast, appear to all Spaniards – and this is precisely the transcendental service that the monarchy, and only the monarchy, can offer them – not as an opportunist government of a particular historical moment or of exclusive and changing ideologies, but rather as the sublime symbol of a permanent national reality and the guarantee of the reconstruction, on the basis of harmony, of Spain, complete and eternal.’45

Franco’s outrage can be discerned both in the unaccustomed (for him) rapidity (19 days) in which he replied and in the unconcealed contempt of his tone. ‘Others might speak to you in the submissive tone imposed by their dynastic fervour or their ambitions as courtiers; but I, when I write to you, can do so only as the Head of State of the Spanish nation addressing the Pretender to the throne.’ He went on, condescendingly, to attribute Don Juan’s position to his ignorance and to lay before him a petulant list of what he regarded as his own achievements.46

In the wake of Allied success in expelling Axis forces from North Africa in June 1943, Don Juan remained on the offensive. He could draw confidence from the fact that monarchists within the regime were beginning to fear for their own futures. At the end of the month, a group of 27 senior Procuradores (parliamentary deputies) from Franco’s pseudo-parliament, the Cortes, appealed to the Caudillo to settle the constitutional question by re-establishing the traditional Spanish Catholic monarchy before the War ended in an inevitable Allied victory. They believed that only the monarchy could avoid Allied retribution for Franco’s pro-Axis stance throughout the War. The signatories came from right across the Francoist spectrum, with representatives from the banks, the Armed Forces, monarchists and even Falangists. The Caudillo reacted swiftly. Even before the manifesto was published, he had ordered the arrest of the Marqués de la Eliseda who was collecting the signatures. As soon as it was published, showing how very little he was interested in his much-vaunted contraste de pareceres (contrast of opinions – his substitute for democratic politics), he dismissed all the signatories from their seats in the Cortes immediately and sacked the five of them who were also members of the Movimiento’s supreme consultative body, the Consejo Nacional.47

The Caudillo’s sense of being under siege by Don Juan was intensified by the fall of Mussolini on 25 July 1943. Don Juan sent Franco a telegram recommending the restoration of the monarchy as his only chance to avoid the fate of the Duce. It embittered even further the tension between the two. Thereafter, Don Juan believed that Franco never forgave him: ‘he always had it in for me after that telegram.’ It was a bizarre measure of Franco’s self-regard that he regarded Don Juan’s action as high treason.48 Mortified, but aware of his own vulnerability, he shelved his resentment for a better moment. Instead, Franco replied with an appeal to Don Juan’s patriotism, begging him not to make any public statement that might weaken the regime.49 The Caudillo had every reason to be worried – his senior generals were swinging more openly behind the cause of Don Juan. Pedro Sainz Rodríguez was informed that a number of them were ready to rise to restore the monarchy, provided that immediate Allied recognition could be arranged by Don Juan. The Caudillo’s anxiety – and his resentment of Don Juan – was exacerbated when he discovered in the late summer that the generals were conspiring. Prompted by Don Juan’s senior representative in Spain, his cousin Prince Alfonso de Orleans Borbón, they met in Seville on 8 September 1943 to discuss the situation and composed a document calling upon Franco to take action to bring back the monarchy.50