полная версия

полная версияThe Continental Monthly, Vol. 6, No 3, September 1864

As much interest is manifested for increased knowledge of solar characteristics, and as many astronomers and numerous amateurs are daily engaged in their investigation, I have thought that the experience of thousands of observations and the final advantages of a host of experiments in combination of lenses and colored glasses, resulting highly favorably to a further elucidation of solar characteristics, would be interesting, especially to such as are engaged in that branch of inquiry.

My experiments have resulted in two important discoveries. First, by a new combination of lenses, I prevent heat from being communicated to the colored glasses, which screen the eye from the blinding effects of solar light, and thus avoid the not infrequent cracking of these glasses from excess of heat, thereby endangering the sight—whereas, by my method, the colored glasses remain as cool after an hour's observation as at the commencement, and no strain or fatigue to the eye is experienced. Secondly, the defining power of the telescope is greatly increased, so that with a good three-and-a-quarter inch acromatic object-glass, with fifty-four inches focal length (mine made by Búron, Paris), I have obtained a clearer view of the physical features of the sun than any described in astronomical works.

In a favorable state of the atmosphere, and when spots are found lying more than halfway between the sun's centre and the margin, or better still, if nearer the margin, when the spots lie more edgeways to the eye, I can see distinctly the relative thickness of the photosphere and the underlying dusky penumbra, which lie on contiguous planes of about equal thickness, like the coatings of an onion. When these spots are nearer the centre of the sun, we see more vertically into their depths, by which I frequently observe a third or cloud stratum, underlying the penumbra, and partially closing the opening, doubtless to screen the underlying globe (which, by contrast with the photosphere, is intensely black) from excessive light, or to render it more diffusive.11 The concentric faculæ are then plainly visible, and do not appear to rise above the surface of the photosphere (as generally described), but rather as depressions in that luminous envelope, frequently breaking entirely through to the penumbra; and when this last parts, forms what are called 'spots.' The delusion in supposing the faculæ to be elevated ridges, appears to me to be owing to the occasional depth of the faculæ breaking down through the photosphere to the dusky penumbra, giving the appearance of a shadow from an elevated ridge. What is still more interesting, in a favorable state of the atmosphere, I can distinctly see over the whole surface of the sun, not occupied by large spots or by faculæ, a network of pores or minute spots in countless numbers, with dividing lines or faculæ-like depressions in the photosphere, separating each little hole, varying in size, some sufficiently large to exhibit irregularities of outline, doubtless frequently combining and forming larger spots.12 When there are no scintillations in the air, the rim or margin of the sun appears to be a perfect circle, as defined, in outline, as if carved. By interposing an adjusted circular card, to cut off the direct rays of the sun, thus improvising an eclipse, not a stray ray of light is seen to dart in any direction from the sun, except what is reflected to the instrument, diffusively, from our atmosphere; thus proving that the corona, the coruscations or flashes of light, seen during a total or nearly total eclipse of the sun by the moon, are not rays direct from the sun, but reflections from lunar snow-clad mountains, into her highly attenuated atmosphere. Solar light, being electric, is not developed as light until reaching the atmosphere of a planet or satellite, or their more solid substance, which would explain why solar light is not diffused through space, and thus account for nocturnal darkness.

The combination of glasses which enabled me to inspect the above details may be stated briefly thus: In the place of my astronomic eyepiece, I use an elongator (obtainable of opticians) to increase the power. Into this I place my terrestrial tube, retaining only the field glasses, and using a microscopic eyepiece of seven eighths of an inch in diameter. Over this I slide a tube containing my colored glasses, one dark blue and two dark green, placed at the outer end of the sliding tube, one and a half inches from the eyeglass. The colored glasses are three quarters of an inch in diameter, and the aperture next the eye in diameter half an inch. The power which I usually employ magnifies but one hundred and fifty diameters; and I use the entire aperture of my object glass. This combination of colored glasses gives a clear dead white to the sun, the most desirable for distinct vision, as all shaded portions, such as spots, however minute, and their underlying dusky penumbra, are thus brought into strong contrasts.

AN ARMY: ITS ORGANIZATION AND MOVEMENTS

FOURTH PAPER

In previous papers we have briefly related the history of the art of war as now practised, stated the functions of the principal staff departments, and mentioned some of the peculiar features of the different arms of military service. It remains to describe the operations of an army in its totality—to show the methods in which its three principal classes of operations—marching, encamping, and fighting—are performed.

The first necessity for rendering an army effective is evidently military discipline, including drill, subordination, and observance of the prescribed regulations. The first is too much considered as the devotion of time and toil to the accomplishment of results based on mere arbitrary rules. The contrary is the truth. Drilling in all its forms—from the lowest to the highest—from the rules for the position of the single soldier to the manœuvres of a brigade—is only instruction in those movements which long experience has proved to be the easiest, quickest, and most available methods of enabling a soldier to discharge his duties: it is not the compulsory observance of rules unfounded on proper reasons, designed merely to give an appearance of uniformity and regularity—merely to make a handsome show on parade. Nothing so much wearies and discourages a new recruit as his drill; he cannot at first understand it, and does not see the reason for it. He exclaims:

'I'm sick of this marching,Pipe-claying and starching.'He thinks he can handle his musket with more convenience and rapidity if he is permitted to carry it and load it as he chooses, instead of going through the formula of motions prescribed in the manual. Perhaps as an individual he might; but when he is only one in a large number, his motions must be regulated, not only by his own convenience, but also by that of his neighbors. Very likely, a person uneducated in the mysteries of dancing would never adopt the polka or schottish step as an expression of exuberance; but if he dances with a company, he must be governed by the rules of the art, or he will be likely to tread on the toes of his companions, and be the cause of casualties. Military drill is constantly approaching greater simplicity, as experience shows that various particulars may be dispensed with. Formerly, when soldiers were kept up as part of the state pageants, they were subjected to numberless petty tribulations of drill, which no longer exist. Pipe-clayed belts, for example, have disappeared, except in the marine corps. Frederick the Great was the first who introduced into drill ease and quickness of execution, and since his day it has been greatly simplified and improved.

One great difficulty in our volunteer force pertains to the institution of a proper subordination. Coming from the same vicinage, often related by the various interests of life, equals at home, officers and men have found it disagreeable to assume the proper relations of their military life. The difficulty has produced two extremes of conduct on the part of officers—either too much laxity and familiarity, or the entire opposite—too great severity. The one breeds contempt among the men, and the other hatred. After the soldier begins to understand the necessities of military life, he sees that his officers should be men of dignity and reliability. He does not respect them unless they preserve a line of conduct corresponding to their superior military position. On the other hand, if he sees that they are inflated by their temporary command, and employ the opportunity to make their authority needlessly felt, and to exercise petty tyranny, he entertains feelings of revenge toward them. A model officer for the volunteer service is one who, quietly assuming the authority incident to his position, makes his men feel that he exercises it only for their own good. Such an officer enters thoroughly into all the details of his command—sees that his men are properly fed, clothed, and sheltered—that they understand their drill, and understand also that its object is to render them more effective and at the same time more secure in the hour of conflict—is careful and pains-taking, and at the same time, in the hour of danger, shares with his men all their exposures. Such an officer will always have a good command. We think there has been a tendency to error in one point of the discipline of the volunteer forces, by transferring to them the system which applied well enough to the regulars. In the latter, by long discipline, each man knows his duty, and if he commits a fault, it is his own act. In the volunteers, the faults of the men are in the majority of cases attributable to the officers. We know some companies in which no man has ever been sent to the guard house, none ever straggled in marching, none ever been missing when ordered into battle. The officers of these companies are such as we have described above. We know other companies—too many—in which the men are constantly straying around the country, constantly found drunk or disorderly, constantly out of the ranks, and constantly absent when they ought to be in line. Invariably the officers of such companies are worthless. If, then, the system of holding officers responsible for the faults of the men, were adopted, a great reform would, in our judgment, be introduced into the service. It is a well-known fact in the army that the character of a regiment, of a brigade, of a division even, can be entirely changed by a change of commanders. A hundred or a thousand men, selected at random from civil life anywhere, will have the same average character; and if the military organization which these hundred or thousand form differs greatly from that of any similar organization, it is attributable entirely to those in command.

Passing to the army at large, the next matter of prominent necessity to be noticed is the infusion in it of a uniform spirit—so as to make all its parts work harmoniously in the production of a single tendency and a single result. This must depend upon the general commanding. It is one of the marks of genius in a commander that he can make his impress on all the fractions of his command, down to the single soldier. An army divided by different opinions of the capacity or character of its commander, different views of policy, can scarcely be successful. Napoleon's power of impressing his men with an idolatry for himself and a confidence in victory is well known. The moral element in the effectiveness of an army is one of great importance. Properly stimulated it increases the endurance and bravery of the soldiers to an amazing degree. Physical ability without moral power behind it, is of little consequence. It is a well-known fact that a man will, in the long run, endure more (proportionately to his powers) than a horse, both being subject to the same tests of fatigue and hunger. A commander with whom an army is thoroughly in accord, and who shows that he is capable of conducting it through battle with no more loss than is admitted to be unavoidable, can make it entirely obedient to his will. The faculty of command is of supreme importance to a general. Without it, all other attainments—though of the highest character—will be unserviceable.

However large bounties may have given inducements for men to enlist as soldiers, it is undeniable that patriotism has been a deciding motive. Under the influence of this, each soldier has entertained an ennobling opinion of himself, and has supposed that he would be received in the character which such a motive impressed on him. He has quickly ascertained, however, when fully entered on his military duties, that the discipline has reduced him from the position of an independent patriot to that of a mere item in the number of the rank and file. Military discipline is based on the theory that soldiers should be mere machines. So far as obedience is concerned, this is certainly correct enough; but discipline in this country, and particularly with volunteers, should never diminish the peculiar American feeling of being 'as good as any other man.' On the contrary, the soldier should be encouraged to hold a high estimation of himself. We do not believe that those soldiers who are mere passive instruments—like the Russians, for example—can be compared with others inspired with individual pride. Yet, perhaps, our discipline has gone too far in the 'machine' direction. To keep up the feeling of patriotism to its intensest glow is a necessity for an American army, and a good general would be careful to make this a prominent characteristic of the impression reflected from his own genius upon his command. Professional fighting is very well in its place, and there are probably thousands who are risking blood and life in our armies, who yet do not cordially sympathize with the objects of the war. But an army must be actuated by a living motive—one of powerful importance; in this war there is room for such a motive to have full play, and it is essential that our soldiers should be incited by no mere abstract inducements, by no mere entreaties to gain victory, but by exhibitions of all the reasons that make our side of the struggle the noblest and holiest that ever engaged the attention of a nation.

But we must leave such discussions, and proceed specifically to the subject of this paper—the methods of moving an army.

A state of war having arrived, it depends upon the Government to decide where the theatre of operations shall be. Usually, in Europe, this has been contracted, containing but few objective points, that is, the places the capture of which is desired; but in our country the theatre of operations may be said to have included the whole South. The places for the operations of armies having been decided on, the Government adopts the necessary measures for assembling forces at the nearest point, and accumulating supplies, as was done at Washington in 1861. A commander is assigned to organize the forces, and at the proper time he moves them to the selected theatre. Now commences the province of strategy, which is defined as 'the art of properly directing masses upon the theatre of war for the defence of our own or the invasion of the enemy's country.' Strategy is often confounded with tactics, but is entirely different—the latter being of an inferior, more contracted and prescribed character, while the former applies to large geographical surfaces, embraces all movements, and has no rules—depending entirely on the genius of the commander to avail himself of circumstances. It is the part of strategy, for instance, so to manœuvre as to mislead the enemy, or to separate his forces, or to fall upon them singly. Tactics, on the contrary, are the rules for producing particular effects, and apply to details. The strategy of the commander brings his forces into the position he has chosen for giving battle; tactics prescribe the various evolutions of the forces by which they take up their assigned positions. It was by strategy that General Grant obtained the position at Petersburg; it was by tactics that his army was able to march with such celerity and precision that the desired objects were attained.

Marches are of two classes—of concentration and of manœuvre. The former, being used merely for the assembling of an army, or conducting it to the theatre of operations, need but little precision; the latter are performed upon the actual theatre of war, often in the presence of the enemy, and require care and skill for their proper conduct. The details of marches are of course governed by the nature of the country in which they are performed, but so far as practicable they are made in two methods—by parallel columns, or by the flank. The former is the most usual and the most preferable in many respects; indeed, the latter is never adopted except when compelled by necessity, or for the purpose of executing some piece of strategy. A careful arrangement of all details by commanders, and a steady persistence in their performance on the part of the troops, are required to permit this class of marches to be made safely in the presence of an enemy.

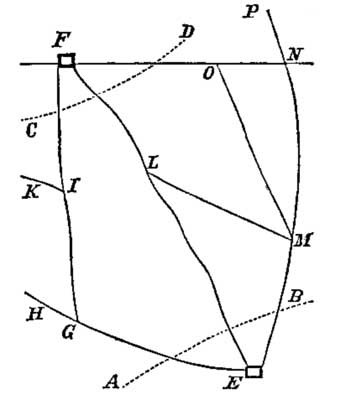

For the use of an army of a hundred thousand men about to march forward against an enemy, all the parallel roads within a space of at least ten miles are needed, and the more of them there are the better, since the columns can thereby be made shorter, and the trains be sent by the interior roads. Where a sufficient number of parallel roads exist, available for the army, it is usual to put about a division on each—sometimes the whole of a corps—according to the nature of the country and the objects to be attained. We will attempt to illustrate the march of an army by columns in the following diagram.

Suppose that E and F are two towns thirty miles apart, and that there are road connections as represented in the diagram. The army represented by the dotted line A B, wishes to move to attack the army C D. Cavalry, followed by infantry columns, would be sent out on the roads E M N and E G I, the cavalry going off toward P and K to protect the flanks, and the infantry taking position at I and O. Meantime another column, behind which are the baggage trains, covered with a rear guard, has moved to L. If the three points I, L, and O are reached simultaneously, the army can safely establish its new line, the baggage trains are entirely protected, and the whole country is occupied as effectually as if every acre were in possession.

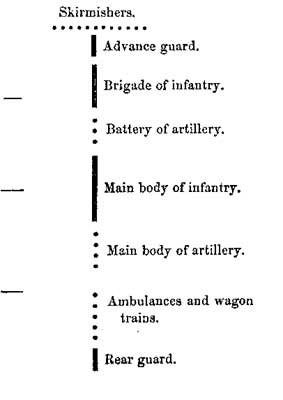

The formation of a marching column varies according to circumstances, but is usually somewhat as follows, when moving toward an enemy:

The dots representing the ambulances and wagon trains do not show the true proportion of these to the rest of the column, and it cannot be given except at too great a sacrifice of space. They occupy more road than all the other parts of the column combined. With the advance guard go the engineers and pioneers, to repair the roads, make bridges, etc.

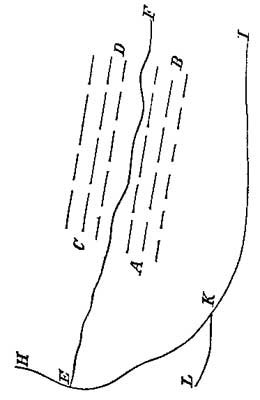

The difficulties and dangers attending a flank march can be made apparent by a diagram:

Let A B and C D represent two armies drawn up against each other in three lines of battle, on opposite sides of a stream, E F. The commander of the army A B, finding he cannot cross and drive the enemy from their works, determines, by a flank march to the left, to go around them, crossing at the point E. In order to effect this he must send his trains off by the road I K L to some interior line, and then slowly unfold his masses upon the single road K E H. By the time the head of his column is at H the rear has not perhaps left K, and thus the whole length of his army is exposed on its side to an attack by the enemy, which may sever it into two unsupporting portions. It will be perceived that to accomplish such marches with security, they must be made in secret as far as possible, until a portion of the marching force reaches the rear of the enemy; the column must be kept compact, and great vigilance must be exercised. In his progress from the Rapidan to the James, General Grant made three movements of this character with entire success, each time putting our forces so far in the rear of the rebels that they were compelled to hasten their own retreat instead of delaying to avail themselves of the opportunity for attacking.

Besides the topography of the country, various circumstances influence the manner in which a march is conducted—particularly the position of the enemy. When following a retreating foe, the cavalry is sent in the advance, supported by some infantry and horse artillery, to harass the rear guard, and, if practicable, delay the retreat until the main army can come up. This was the case in the peninsula campaign, from Yorktown to the Chickahominy. Again, the exact position of the enemy may not be known, or he may have large bodies in different places, so that his intentions cannot be surmised. It is then necessary to scatter the army so as to cover a number of threatened points, care being exercised to have all the different bodies within supporting distances, and to be on guard against a sudden concentration of the enemy between them. This was the case in the campaign which ended so gloriously at Gettysburg. The rebels were then threatening both Harrisburg and Baltimore, and the two extremities of our army were over thirty miles apart, so as to be concentrated either on the right, left, or centre, as events might determine. It happened that a collision was brought on at Gettysburg, and both armies immediately concentrated there. The corps on the right of our army was obliged to march about thirty-two miles, performing the distance in about eighteen or nineteen hours, and arriving in time to participate in the second day's battle. As much skill is evinced by a commander in preliminary manœuvring marches and the assignment of positions to the different portions of his army as in the direction of a battle. Napoleon gained many of his victories through the effects of such manœuvres.

Time is a very important element in marching. An army which can march five miles a day more than its opponent will almost certainly be victorious, for it can go to his flank, or assail him when unprepared, Frederick the Great achieved his successes by imparting mobility to his troops, and Napoleon also was a master of that peculiar feature in that faculty of command of which we have before spoken, that enables a leader to obtain from his men the maximum amount of continued exertion. To achieve facility in marching, all the equipments of the soldiers should be as light as possible, and the columns should be encumbered with no more trains than are absolutely indispensable. Officers of the highest class must be prepared to forego unnecessary luxuries, and to march with nothing more than a blanket, a change of clothing, and rations for a few days in their haversacks.

When a march is contemplated, orders are issued from the general headquarters prescribing all the details—the time at which each corps is to start, the roads to be taken, the precautions to be observed, and the points to be gained. Usually an early hour in the morning is fixed for the commencement of the march. If not in the immediate presence of the enemy, and a surprise is not intended, the reveillé is beaten about three o'clock, and the sleepy soldiers arouse from their beds on the ground, pack up their tents, blankets, and equipments, get a hasty breakfast, and fall into their ranks. If some commander—perhaps of a regiment only—has been dilatory, the whole movement is delayed. Many well-formed plans have been defeated by the indolence of a subordinate commander and his failure to put his troops in motion at the designated hour. Such a delay may embarrass the whole army by detaining other portions, whose movements are to be governed by those of the belated fragment. At four o'clock, if orders have been obeyed, the long columns are moving. Perhaps four or five hours are occupied in filing out into the road. While the sun is rising and the birds engaged at their matins, the troops are trudging along at that pace of three miles an hour, which seems so tardy, but which, persisted in day after day, traverses so great a distance. Every hour there is ten or fifteen minutes' halt, enabling the rear to close up, and the men to relieve themselves temporarily of their guns and knapsacks. Soon the heat commences to grow oppressive, the dust rises in suffocating clouds, knapsacks weigh like lead, and the artillery horses pant as they drag the heavy guns. But the steady tramp must be continued till about eleven o'clock, when a general halt under the shelter of some cool woods, by the side of a stream, is ordered. Two or three hours of welcome rest are here employed in dinner and finishing the broken morning's nap. After the intenser heat of the day is past, the tramp recommences, and continues till six or seven o'clock, when the place appointed for encamping is reached. Soon white tents cover every hill and plain and valley, the weary animals are unharnessed, trees and fence rails disappear rapidly to feed the consuming camp fires, there is a universal buzz formed from the laugh, the song, the shout, and the talking of twenty thousand voices: it gradually subsides, the fires grow dim, and silence and darkness fall upon the scene.