полная версия

полная версияHandwork in Wood

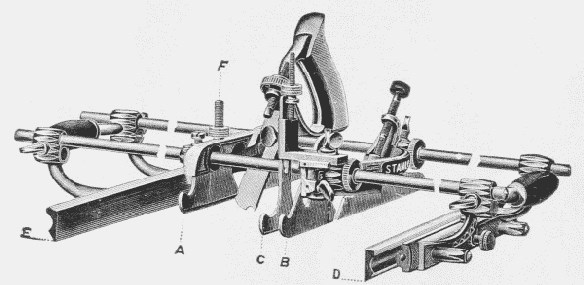

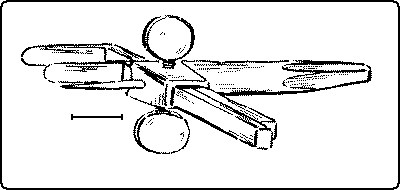

Fig. 117. Universal Plane.

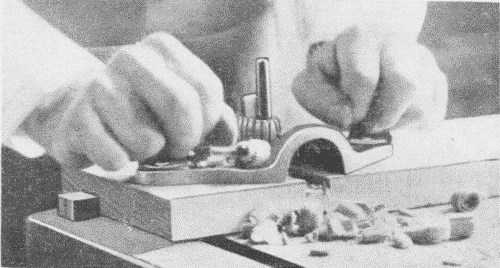

The Use of the Universal Plane. Insert the proper cutter, adjusting it so that the portion of it in line with the main stock, A, will project below the sole the proper distance for cutting.

Adjust the bottom of the sliding section, B, so that the lowest portion of the cutter will project the proper distance below it for cutting. Tighten the check nuts on the transverse arms and then tighten the thumb-screws which secure the sliding section to the arms. The sliding section is not always necessary, as in a narrow rabbet or bead.

When an additional support is needed for the cutter, the auxiliary center bottom, C, may be adjusted in front of it. This may also be used as a stop.

Adjust one or both of the fences, D and E, and fasten with the thumb-screws. Adjust the depth-gage, F, at the proper depth.

For a dado remove the fences and set the spurs parallel with the edges of the cutter. Insert the long adjustable stop on the left hand of the sliding section. For slitting, insert the cutter and stop on the right side of the main stock and use either fence for a guide.

For a chamfer, insert the desired cutter, and tilt the rosewood guides on the fences to the required angle. For chamfer beading use in the same manner, and gradually feed the cutter down by means of the adjusting thumb-nut.

There are also a number of planelike tools such as the following:

The spoke-shave, Fig. 118. works on the same principle as a plane, except that the guiding surface is very short. This adapts it to work with curved outlines. It is a sort of regulated draw-shave. It is sometimes made of iron with an adjustable mouth, which is a convenient form for beginners to use, and is easy to sharpen. The pattern-makers spokeshave, Fig. 119, which has a wooden frame, is better suited to more careful work. The method of using the spokeshave is shown in Fig. 120.

Fig. 118. Iron Spokeshave. Fig. 119. Pattern-maker's Spokeshave.

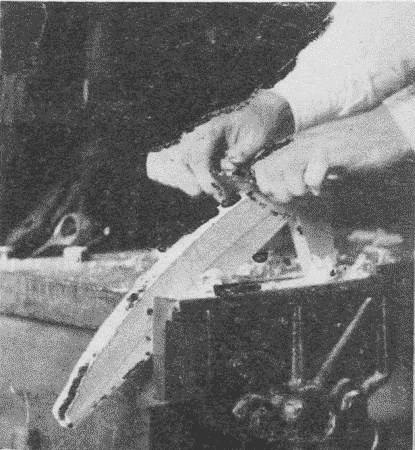

Fig. 120. Using a Spokeshave.

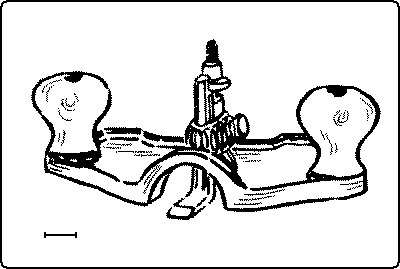

The router-plane, Figs. 121 and 122, is used to lower a certain part of a surface and yet keep it parallel with the surrounding part, and it is particularly useful in cutting panels, dadoes, and grooves. The cutter has to be adjusted for each successive cut. Where there are a number of dadoes to be cut of the same depth, it is wise not to finish them one at a time, but to carry on the cutting of all together, lowering the cutter after each round. In this way all the dadoes will be finished at exactly the same depth.

Fig. 121. Router-Plane.

Fig. 122. Using a Router-Plane.

The dowel-pointer, Fig. 123, is a convenient tool for removing the sharp edges from the ends of dowel pins. It is held in a brace. The cutter is adjustable and is removable for sharpening.

The cornering tool, Fig. 124, is a simple device for rounding sharp corners. A cutter at each end cuts both ways so that it can be used with the grain without changing the position of the work. The depth of the cut is fixed.

Fig. 123. Dowel-Pointer. Fig. 124. Cornering Tool.

2. BORING TOOLS

Some boring tools, like awls, force the material apart, and some, like augers, remove material.

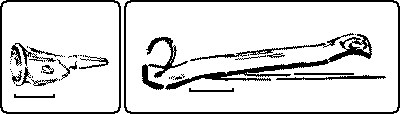

The brad-awl, Fig. 125, is wedge-shaped, and hence care needs to be taken in using it to keep the edge across the grain so as to avoid splitting the wood, especially thin wood. The size is indicated by the length of the blade when new,—a stupid method. The awl is useful for making small holes in soft wood, and it can readily be sharpened by grinding.

Gimlets and drills are alike in that they cut away material, but unlike in that the cutting edge of the gimlet is on the side, while the cutting edge of the drill is on the end.

Twist-drills, Fig. 126, are very hard and may be used in drilling metal. They are therefore useful where there is danger of meeting nails, as in repair work. Their sizes are indicated by a special drill gage, Fig. 220, p. 116.

Twist-bits, Fig. 127, are like twist-drills except that they are not hard enough to use for metal. Their sizes are indicated on the tang in 32nds of an inch. Both twist-bits and drill-bits have the advantage over gimlet-bits in that they are less likely to split the wood.

Twist-bits and twist-drills are sharpened on a grindstone, care being taken to preserve the original angle of the cutting edge so that the edge will meet the wood and there will be clearance.

German gimlet-bits, Fig. 128, have the advantage of centering well. The size is indicated on the tang in 32nds of an inch. They are useful in boring holes for short blunt screws as well as deep holes. They cannot be sharpened readily but are cheap and easily replaced.

Bit-point drills, Fig. 129, are useful for accurate work, but are expensive.

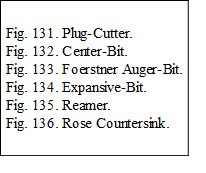

Auger-bits, Fig. 130, have several important features. The spur centers the bit in its motion, and since it is in the form of a pointed screw draws the auger into the wood. Two sharp nibs on either side score the circle, out of which the lips cut the shavings, which are then carried out of the hole by the main screw of the tool. The size of auger-bits is indicated by a figure on the tang in 16ths of an inch. Thus 9 means a diameter of 9⁄16".

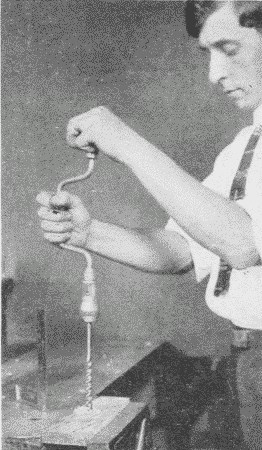

There are three chief precautions to be taken in using auger-bits. (1) One is to bore perpendicularly to the surface. A good way to do this is to lay the work flat, either on the bench or in the vise, and sight first from the front and then from the side of the work, to see that the bit is perpendicular both ways. The test may also be made with the try-square, Fig. 137, or with a plumb-line, either by the worker, or in difficult pieces, by a fellow worker. The sense of perpendicularity, however, should constantly be cultivated. (2) Another precaution is that, in thru boring, the holes should not be bored quite thru from one side, lest the wood be splintered off on the back. When the spur pricks thru, the bit should be removed, the piece turned over, and the boring finished, putting the spur in the hole which is pricked thru in boring from the first side. It is seldom necessary to press against the knob of the brace in boring, as the thread on the spur will pull the bit thru, especially in soft wood. Indeed, as the bit reaches nearly thru the board, if the knob is gently pulled back, then when the spur pricks thru the bit will be pulled out of its hole. This avoids the necessity of constantly watching the back of the board to see if the spur is thru. (3) In stop boring, as in boring for dowels or in making a blind mortise, care should be taken not to bore thru the piece. For this purpose an auger-bit-gage, Fig. 219, p. 116, may be used, or a block of wood of the proper length thru which a hole has been bored, may be slipped over the bit, or the length of bit may be noted before boring, and then the length of the projecting portion deducted, or the number of turns needed to reach the required depth may be counted on a trial piece. Tying a string around a bit, or making a chalk mark on it is folly.

Fig. 137. Using a Try-Square as a Guide in Boring.

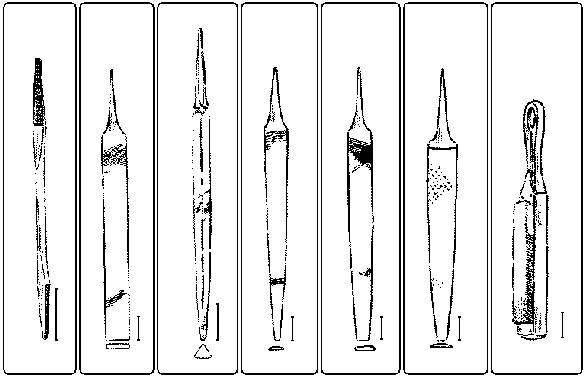

Auger-bits are sharpened with an auger-bit file, Fig. 142, p. 90, a small flat file with two narrow safe edges at one end and two wide safe edges at the other. The "nibs" should be filed on the inside so that the diameter of the cut may remain as large as that of the body of the bit. The cutting lip should be sharpened from the side toward the spur, care being taken to preserve the original angle so as to give clearance. If sharpened from the upper side, that is, the side toward the shank, the nibs will tend to become shorter.

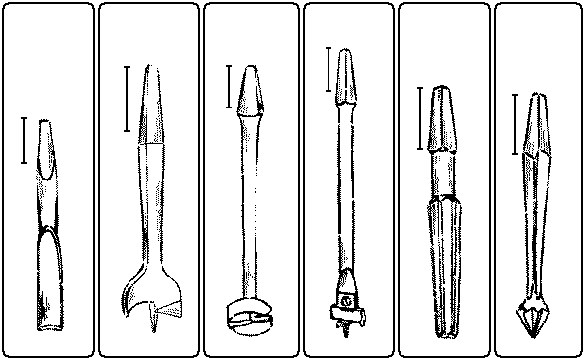

The plug-cutter, Fig. 131, is useful for cutting plugs with which to cover the heads of screws that are deeply countersunk.

Center-bits, Fig. 132, work on the same principle as auger-bits, except that the spurs have no screw, and hence have to be pushed forcibly into the wood. Sizes are given in 16ths of an inch. They are useful for soft wood, and in boring large holes in thin material which is likely to split. They are sharpened in the same way as auger-bits.

Foerstner bits, Fig. 133, are peculiar in having no spur, but are centered by a sharp edge around the circumference. The size is indicated on the tang, in 16ths of an inch. They are useful in boring into end grain, and in boring part way into wood so thin that a spur would pierce thru. They can be sharpened only with special appliances.

Expansive-bits, Fig. 134, are so made as to bore holes of different sizes by adjusting the movable nib and cutter. There are two sizes, the small one with two cutters, boring from ½" to 1½" and the large one with three cutters boring from ⅞" to 4". They are very useful on particular occasions, but have to be used with care.

Reamers, Fig. 135, are used for enlarging holes already made. They are made square, half-round and six cornered in shape.

Countersinks, Fig. 136, are reamers in the shape of a flat cone, and are used to make holes for the heads of screws. The rose countersink is the most satisfactory form.

Fig 138. Washer-Cutter.

The washer-cutter, Fig. 138, is useful not only for cutting out washers but also for cutting holes in thin wood. The size is adjustable.

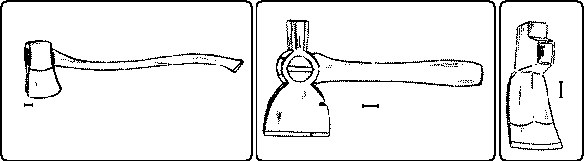

3. CHOPPING TOOLSThe primitive celt, which was hardly more than a wedge, has been differentiated into three modern hand tools, the chisel, see above, p. 53, the ax, Fig. 139, and the adze, Fig. 141.

The ax has also been differentiated into the hatchet, with a short handle, for use with one hand, while the ax-handle is long, for use with two hands. Its shape is an adaption to its manner of use. It is oval in order to be strongest in the direction of the blow and also in order that the axman may feel and guide the direction of the blade. The curve at the end is to avoid the awkward raising of the left hand at the moment of striking the blow, and the knob keeps it from slipping thru the hand. In both ax and hatchet there is a two-beveled edge. This is for the sake of facility in cutting into the wood at any angle.

There are two principal forms, the common ax and the two bitted ax, the latter used chiefly in lumbering. There is also a wedge-shaped ax for splitting wood. As among all tools, there is among axes a great variety for special uses.

The hatchet has, beside the cutting edge, a head for driving nails, and a notch for drawing them, thus combining three tools in one. The shingling hatchet, Fig. 140, is a type of this.

The adze, the carpenter's house adze, Fig. 141, is flat on the lower side, since its use is for straightening surfaces.

WOOD HAND TOOLSReferences:10

(1) Cutting.

Goss, p. 22.

Smith, R. H., pp. 1-8.

Chisel.

Barnard, pp. 59-73.

Selden, pp. 44-50, 145-147.

Barter, pp. 93-96.

Griffith, pp. 53-64.

Goss, pp. 20-26.

Sickels, pp. 64-67.

Wheeler, 357, 421, 442.

Knife.

Barnard, pp. 48-58.

Selden, pp. 26-28, 158.

Saw.

Griffith, pp. 20-27.

Barnard, pp. 114-124.

Selden, pp. 41-43, 179-182.

Wheeler, pp. 466-473.

Hammacher, pp. 309-366.

Goss, pp. 26-41.

Sickels, pp. 76-79, 84.

Smith, R. H., 43-55.

Diston, pp. 129-138.

Plane.

Barnard, pp. 74-80.

Selden, pp. 11-26, 165-175.

Sickels pp. 72-75, 116.

Wheeler, pp. 445-458.

Hammacher, pp. 377-400.

Smith, R. H., pp. 16-31.

Larsson, p. 19.

Goss, pp. 41-52.

Barter, pp. 96-109.

Griffith, pp. 28-45.

(2) Boring Tools.

Barnard, pp. 125-135.

Goss, pp. 53-59.

Griffith, pp. 47-52.

Seldon, pp. 38-40, 141-144.

Wheeler, pp. 353-356.

(3) Chopping Tools.

Barnard, pp. 80-88.

Chapter IV, Continued.

WOOD HAND TOOLS

4. SCRAPING TOOLSScraping tools are of such nature that they can only abrade or smooth surfaces.

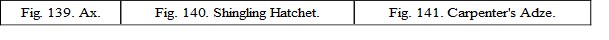

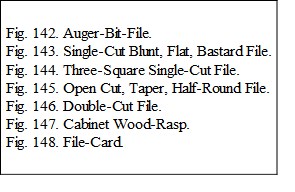

Files. Figs. 142-146, are formed with a series of cutting edges or teeth. These teeth are cut when the metal is soft and cold and then the tool is hardened. There are in use at least three thousand varieties of files, each of which is adapted to its particular purpose. Lengths are measured from point to heel exclusive of the tang. They are classified: (1) according to their outlines into blunt, (i. e., having a uniform cross section thruout), and taper; (2) according to the shape of their cross-section, into flat, square, three-square or triangular, knife, round or rat-tail, half-round, etc.; (3) according to the manner of their serrations, into single cut or "float" (having single, unbroken, parallel, chisel cuts across the surface), double-cut, (having two sets of chisel cuts crossing each other obliquely,) open cut, (having series of parallel cuts, slightly staggered,) and safe edge, (or side,) having one or more uncut surfaces; and (4) according to the fineness of the cut, as rough, bastard, second cut, smooth, and dead smooth. The "mill file," a very common form, is a flat, tapered, single-cut file.

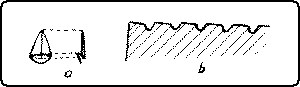

Rasps, Fig. 147, differ from files in that instead of having cutting teeth made by lines, coarse projections are made by making indentations with a triangular point when the iron is soft. The difference between files and rasps is clearly shown in Fig. 149.

Fig. 149. a. Diagram of a Rasp Tooth.

b. Cross-Section of a Single-Cut File.

It is a good rule that files and rasps are to be used on wood only as a last resort, when no cutting tool will serve. Great care must be taken to file flat, not letting the tool rock. It is better to file only on the forward stroke, for that is the way the teeth are made to cut, and a flatter surface is more likely to be obtained.

Both files and rasps can be cleaned with a file-card, Fig. 148. They are sometimes sharpened with a sandblast, but ordinarily when dull are discarded.

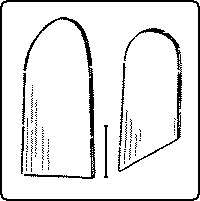

Scrapers are thin, flat pieces of steel. They may be rectangular, or some of the edges may be curved. For scraping hollow surfaces curved scrapers of various shapes are necessary. Convenient shapes are shown in Fig. 150. The cutting power of scrapers depends upon the delicate burr or feather along their edges. When properly sharpened they take off not dust but fine shavings. Scrapers are particularly useful in smoothing cross-grained pieces of wood, and in cleaning off glue, old varnish, etc.

Fig. 150. Molding-Scrapers.

There are various devices for holding scrapers in frames or handles, such as the scraper-plane, Fig. 111, p. 79, the veneer-scraper, and box-scrapers. The veneer-scraper, Fig. 151, has the advantage that the blade may be sprung to a slight curve by a thumb-screw in the middle of the back, just as an ordinary scraper is when held in the hands.

Fig. 151. Using a Veneer-Scraper.

In use, Fig. 152, the scraper may be either pushed or pulled. When pushed, the scraper is held firmly in both hands, the fingers on the forward and the thumbs on the back side. It is tilted forward, away from the operator, far enough so that it will not chatter and is bowed back slightly, by pressure of the thumbs, so that there is no risk of the corners digging in. When pulled the position is reversed.

Fig. 152. Using a Cabinet-Scraper.

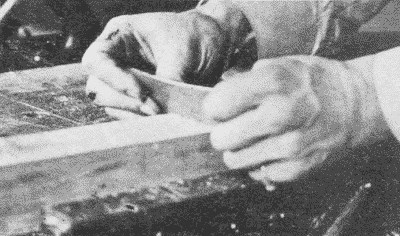

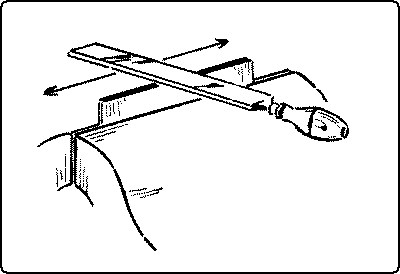

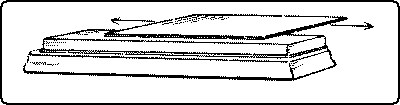

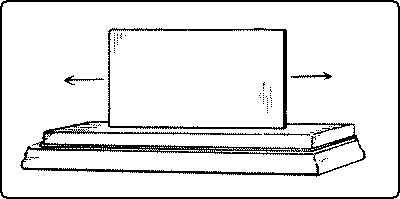

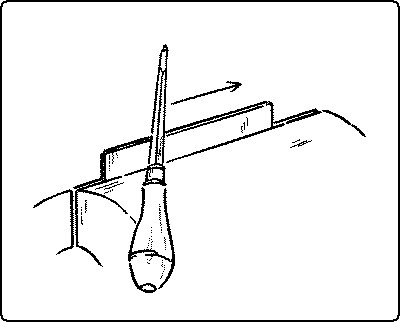

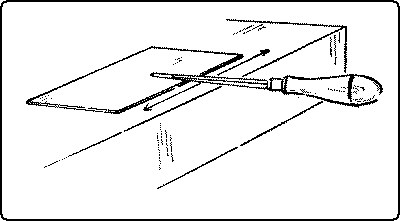

One method of sharpening the scraper is as follows: the scraper is first brought to the desired shape, straight or curved. This may be done either by grinding on the grindstone or by filing with a smooth, flat file, the scraper, while held in a vise. The edge is then carefully draw-filed, i. e., the file, a smooth one, is held (one hand at each end) directly at right angles to the edge of the scraper, Fig. 153, and moved sidewise from end to end of the scraper, until the edge is quite square with the sides. Then the scraper is laid flat on the oilstone and rubbed, first on one side and then on the other till the sides are bright and smooth along the edge, Fig. 154. Then it is set on edge on the stone and rubbed till there are two sharp square corners all along the edge, Fig. 155. Then it is put in the vise again and by means of a burnisher, or scraper steel, both of these corners are carefully turned or bent over so as to form a fine burr. This is done by tipping the scraper steel at a slight angle with the edge and rubbing it firmly along the sharp corner, Fig. 156.

Fig. 153. Sharpening a Cabinet-Scraper: 1st Step, Drawfiling.

Fig. 154. Sharpening a Cabinet-Scraper: 2nd Step, Whetting.

Fig. 155. Sharpening a Cabinet-Scraper: 3rd Step, Removing the Wire-Edge.

Fig. 156. Sharpening a Cabinet-Scraper: 4th Step, Turning the Edge.

To resharpen the scraper it is not necessary to file it afresh every time, but only to flatten out the edges and turn them again with slightly more bevel. Instead of using the oilstone an easier, tho less perfect, way to flatten out the burr on the edges is to lay the scraper flat on the bench near the edge. The scraper steel is then passed rapidly to and fro on the flat side of the scraper, Fig. 157. After that the edge should be turned as before.

Fig. 157. Resharpening a Cabinet-Scraper: Flattening the Edge.

Sandpaper. The "sand" is crushed quartz and is very hard and sharp. Other materials on paper or cloth are also used, as carborundum, emery, and so on. Sandpaper comes in various grades of coarseness from No. 00 (the finest) to No. 3, indicated on the back of each sheet. For ordinary purposes No. 00 and No. 1 are sufficient. Sandpaper sheets may readily be torn by placing the sanded side down, one-half of the sheet projecting over the square edge of the bench. With a quick downward motion the projecting portion easily parts. Or it may be torn straight by laying the sandpaper on a bench, sand side down, holding the teeth of a back-saw along the line to be torn. In this case, the smooth surface of the sandpaper would be against the saw.

Sandpaper should never be used to scrape and scrub work into shape, but only to obtain an extra smoothness. Nor ordinarily should it be used on a piece of wood until all the work with cutting tools is done, for the fine particles of sand remaining in the wood dull the edge of the tool. Sometimes in a piece of cross-grained wood rough places will be discovered by sandpapering. The surface should then be wiped free of sand and scraped before using a cutting tool again. In order to avoid cross scratches, work should be "sanded" with the grain, even if this takes much trouble. For flat surfaces, and to touch off edges, it is best to wrap the sandpaper over a rectangular block of wood, of which the corners are slightly rounded, or it may be fitted over special shapes of wood for specially shaped surfaces. The objection to using the thumb or fingers instead of a block, is that the soft portions of the wood are cut down faster than the hard portions, whereas the use of a block tends to keep the surface even.

Steel wool is made by turning off fine shavings from the edges of a number of thin discs of steel, held together in a lathe. There are various grades of coarseness, from No. 00 to No. 3. Its uses are manifold: as a substitute for sandpaper, especially on curved surfaces, to clean up paint, and to rub down shellac to an "egg-shell" finish. Like sandpaper it should not be used till all the work with cutting tools is done. It can be manipulated until utterly worn out.

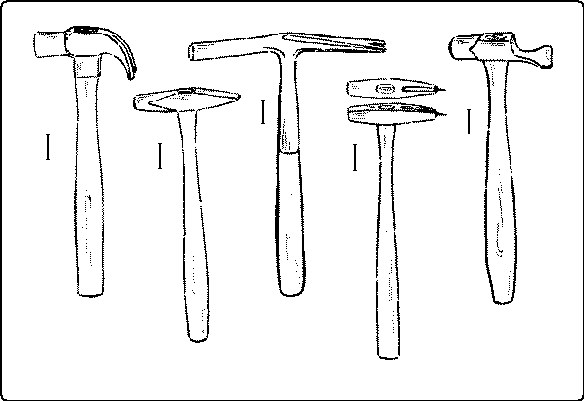

5. POUNDING TOOLSThe hammer consists of two distinct parts, the head and the handle. The head is made of steel, so hard that it will not be indented by hitting against nails or the butt of nailsets, punches, etc., which are comparatively soft. It can easily be injured tho, by being driven against steel harder than itself. The handle is of hickory and of an oval shape to prevent its twisting in the hand.

Hammers may be classified as follows: (1) hammers for striking blows only; as, the blacksmith's hammer and the stone-mason's hammer, and (2) compound hammers, which consist of two tools combined, the face for striking, and the "peen" which may be a claw, pick, wedge, shovel, chisel, awl or round head for other uses. There are altogether about fifty styles of hammers varying in size from a jeweler's hammer to a blacksmith's great straight-handled sledge-hammer, weighing twenty pounds or more. They are named mostly according to their uses; as, the riveting-hammer, Fig. 159, the upholsterer's hammer, Fig. 160, the veneering-hammer, Fig. 162, etc. Magnetized hammers, Fig. 161, are used in many trades for driving brads and tacks, where it is hard to hold them in place with the fingers.

In the "bell-faced" hammer, the face is slightly convex, in order that the last blow in driving nails may set the nail-head below the surface. It is more difficult to strike a square blow with it than with a plain-faced hammer. For ordinary woodwork the plain-faced, that is, flat-faced claw-hammer, Fig. 158, is best. It is commonly used in carpenter work.

It is essential that the face of the hammer be kept free from glue in order to avoid its sticking on the nail-head and so bending the nail. Hammers should be used to hit iron only; for hitting wood, mallets are used. In striking with the hammer, the wrist, the elbow and the shoulder are one or all brought into play, according to the hardness of the blow. The essential precautions are that the handle be grasped at the end, that the blow be square and quick, and that the wood be not injured. At the last blow the hammer should not follow the nail, but should be brought back with a quick rebound. To send the nail below the surface, a nailset is used. (See below.)