полная версия

полная версияThe Continental Monthly , Vol. 2 No. 5, November 1862

It may be inferred that no man in the concern works harder than its owner, and we believe that this is acknowledged by all its employés. Day after day he wears the harness of silent and patient toil.

It is not generally known that during these hours of application, and while engrossed in the management of his immense operations, no one is allowed to address him personally until his errand or business shall have been first laid before a subordinate. If it is of such a character that that gentleman can attend to it, it goes no farther, and hence it vests with him to communicate it to his principal. To illustrate this circumstance, we relate the following incident: A few weeks ago a person entered the wholesale department, with an air of great importance, and demanded to see the proprietor. That proprietor could very easily be seen, as he was sitting in his office, but the stranger was courteously met by the assistant, with the usual inquiry as to the nature of his business. The stranger, who was a Government man, bristled up and exclaimed, indignantly, 'Sir, I come from Mr. Lincoln, and shall tell my business to no one but Mr. Stewart.' 'Sir,' replied the inevitable Mr. Brown, 'if Mr. Lincoln himself were to come here, he would not see Mr. Stewart until he should have first told me his business.'

The amount of annual sales made at this establishment is not known outside of the circle of managers, but may be variously estimated at from ten to thirty millions. This includes the retail department, whose daily trade varies, according to weather and season, from three thousand to twelve thousand dollars per day. To supply this vast demand for goods, Mr. Stewart has agencies in Paris, London, Manchester, Belfast, Lyons, and other European marts. Two of the above cities are the permanent residences of his partners; and while Mr. Fox represents the house in Manchester, Mr. Warton occupies the same position in Paris. These gentlemen are the only partners of the great house of A.T. Stewart & Co.

The marble block which the firm now occupies was built nearly twenty years ago. It had been the site of an old-fashioned hotel—which, like many others of its class, bore the name of 'Washington,' and which was eventually destroyed by fire. Mr. Stewart bought the plot at auction for less than $70,000, a sum which now would be considered beneath half its value. To this was subsequently added adjacent lots in Broadway, Reade and Chambers streets, and the present magnificent pile reared. To such of our readers as walk Broadway, we need not add any detail of its dimensions, nor mention what is now well known, that, large as it is, it is still too small for the increasing business. Hence another mercantile palace has been erected by Mr. Stewart in Broadway near Tenth street. This is intended for the retail trade, and is, no doubt, the most convenient, as well as the most splendid structure of the kind in the world. After the retail department shall have been thus removed up town the present store will be devoted to the wholesale trade.

If any of our readers should inquire what impulse moves the energies of one whose circumstances might warrant a life of ease, we presume that the reply would be force of character and the strength of habit. Mr. Stewart has an empire in the world of merchandise which he can neither be expected to resign or abdicate. We cannot regret that law of centralization which builds up one marble palace, where hundreds have failed utterly to make a living. Centralization of trade has its objections, and yet, upon the whole, there is, no doubt, a much healthier and happier condition prevailing among the parties connected with Mr. Stewart, than would be found among the struggling concerns (say fifty or more) whose place he has taken. Centralization is a law in trade whose movement crushes the weak by an inevitable step, while, by compelling them to take refuge beneath the protection of the strong it affords a better condition than the one from which they have been driven. To his early perception of this law Mr. Stewart largely owes his present colossal fortune.

UNHEEDED GROWTH

As on the top of Lebanon,Slowly the Temple grew,All unobserved, though every shaftA giant shadow threw:Unheeded, though the golden pompOf ponderous roof and spire,Wrought in the chambers of the earth,Like subterranean fire:Until the huge translated pile,By brother kings upreared,On Zion's hill, enthroned at last,In silence reappeared.So, not with observation comesGod's kingdom in the heart;But like that Temple, silently,With golden doors apart.And all the Mighty Ones that watch,With folded wings above,Trembling with awe, now stoop to earth,On messages of love.Another Temple riseth fast,Unbuilt of mortal hands,Upheaving to the battle-blastOf Freedom's conquering bands!The bannered host—the darkened skies—The thunderings all about,Foreshadow but a Nation's birth,Answering a Nation's shout!RED, YELLOW, AND BLUE

Alas for the old fashions! Wonder, incredulity, curiosity, and a crowd of primitive sensations, the whooping host that greeted, like misformed brutes on Circean shores, the steamboat and the telegraph, are passing away on a Lethean tide, and our mysteries are departing from among us. The intelligence which so long gazed wistfully upon the barred door of nature, or picked unsuccessfully at the bolts, with skeleton theories, and vague speculations, had learned to try the 'open sesame' of science. The master key is turning, the shafts yield, and already a dim glory shines through.

While the strides of a positive philosophy are crippled by enthusiastic rhapsodies about intuition and instinct, her footsteps are still indelible, and her progress is certain and accelerating. Reason is written on her brow; she appeals to the universal gift, and denies the authoritative dictations of fallible genius, as much as a moral equality disallows the divine right of kings. Speculators among stars, speculators among sounds and colors, are the skirmishers in front of an intellectual post, whose tread reverberates but little in their rear. Accoutred with a few empiric facts and inductive minds, they aspire to beautiful and stable theories, whence they may descend, by deductive steps, accurate even to mathematical absoluteness, to the very arcana of what has been the inexplicable. To them the true, the beautiful, must be facts, defined, realized, and vigorously analyzed. Visible embodiments of an incomprehensible grace must be disintegrated, and the thinnest essences escape not the analytical rack whereon they confess the causal entity of their composition. 'Broad-browed genius' may toss his locks in the studio redolent of art; his eye may light, and his nervous fingers print the grand creation on the canvas. The divine afflatus is in his nostrils; it is his spirit, and his picture is the reflex of his soul. But keen-eyed Science lays a shadowy hand upon the 'holy coloring,' and says: 'Truly, the harmony is beautiful; it has pleased a sympathetic instinct from the first. Yet, from the first, my laws have been upon it—inexorable laws, which answer to the mind as instinct echoes to the soul.'

The august simile of the philosopher, who likened the world to a vast animal, is appearing each day as too real for poetry. The ocean lungs pulse a gigantic breath at every tide, her continental limbs vibrate with light and electricity, her Cyclopean fires burn within, and her atmosphere, ever giving, ever receiving, subserves the stupendous equilibrium, and betrays the universal motion. Motion is material life; from the molecular quiverings in the crystal diamond, to the light vibrations of a meridian sun—from the half-smothered sound of a whispered love, to the whirl of the uttermost orb in space, there is life in moving matter, as perfect in particulars, and as magnificent in range, as the animation which swells the tiny lung of the polyp, or vitalizes the uncouth python floundering in the saurian slime of a half-cooled planet.

When a polar continent heaves from the bosom of the deep, or when the inquiring eye rests upon the serrated rock, the antique victim of some drift-dispersing glacier, the mind perceives the effects and recognizes the existence of nature's omnipotent muscles, and their appalling power.

But that adventurer who chases the chain of necessity to the sources of this grand instability, is merged at once in a haze of speculations, beautiful as sunlight through morning mists, but uncertain as the veriest chimeras. While beyond the idea of comprehensive motion the colossal symmetry of Truth expands in ultimate outlines, her features are shrouded, but in such an attractive clare-obscure of inviting analogies and semi-satisfying glimpses, that the temptation to guess at the ideal face almost overpowers the desire to kiss the real and shining feet below. Unfortunately, there is the domain of the myths and immaterials, there is the home of the law and the force, there dwell the Odyles, the electricities, the magnetisms, and affinities, and there the speculative Æneas pursues shadows more fleeting than the Stygian ghosts, and the grasp of the metaphysician closes on shapes whose embrace is vacancy. The bark that ploughs within this mystic expanse, sheds from its cleaving keel but coruscations of phosphorescent sparkles, which glimmer and quench in a gloom that Egyptian seers never penetrated, and modern guessers cannot conjecture through. There is, indeed, 'oak and triple brass' upon his breast who steeps his lips in the chalice of the Rosicrucian, and the doom of Prometheus is the fabled defeat which is waiting for the wanderer in those opaque spaces. While we warily, therefore, tread not upon the ground whose trespass brought the vulture of unfilled desire, the craving void for visionary lore upon the heaven-born, earth-punished speculator, we can still find flowery paths and full fruition, in meadows wherein the light of reason requires no support from the ignes fatui of imagination; meadows after all so broad, that did not metaphysics 'teach man his tether,' they would seem illimitable. The book of nature is not spread before us, turning leaf after leaf at every sunrise, with new delineations on every page, to be stared at with vacant inanity, or criticized with imbecile verbosity. The rivulet does not tinkle and the sky does not look blue that people may feed the ear alone with the one, or satisfy the eye alone with the other; the nerves which carry the sensation to the brain, flutter with the news, and knock at the house of mind for explanation. We do not anticipate being hurried into any extravaganza about the rural felicity of green trees, clinking cowbells, cane chairs, and cigars, when we recall to the trainer of surburban vines the harmony, the analogy, the relationship, which he must have observed between sounds and colors in nature's album of melodies.

When, at evening, the zenith blue melts away toward the horizon in dreamy violet, and the retreating sun leaves limber shafts of orange light, like Parthian arrows, among the green branches of the elms, what sounds can charm the ear like the soft chirrup of the cricket, the homely drone of the hive-seeking bee, and the cool rustle of the breeze through the tops of the spring-sodden water grasses? How fondly the mind blends the evening colors and the incipient voices of the night! 'Oh,' says the metaphysician, 'this is association: just so a strain of music reminds you of a fine passage in a book you have read, or a beautiful tone in a picture you have seen; just so the Ranz des Vaches bears the exile to the timber house, with shady leaves, corbelled and strut-supported, whose very weakness appeals to the avalanche that shakes an icicly beard in monition from the impeding crags.'

Well, let association play her part in some cases; when a habit has necessitated the recurrence of two distinct ideas together, they will certainly be associated at times when the habit is gone; but suppose the analogy is felt when the ideas have never before been in juxtaposition, or when there has even been no sensation at all to generate one of the notions. How, for instance, did the sightless imaginer ever conceive that red must be like the sound of the trumpet? Simply because the analogy between color and music is deeper than the idea of either, more absolute than association could make it; because certain tints are calculated to produce exactly similar impressions on the eye that certain sounds do upon the ear; or, to use a mathematical turn of expression, because some color [Greek: x] is to the eye as some sound [Greek: x] is to the ear.

That this mathematical turn of expression is no vagary, but perfectly germane to the subject, and accurate in application, we propose to prove to those who love coincidences and analogies sufficiently to fish them out of a little dilute science.

Light and sound are the daughters of motion. Color and music, the ethereal and aërial offspring of this ancestry, born with the world, fostered in Biblical times, expanded in China and Egypt, living on the painted jar, and breathing in the oaten reed, deified in Greece, and analyzed to-day, are natural cousins at the least, and they have come from the spacious home of their progenitor, upon our dusky and silent sphere, like Peace and Goodwill, with hands bound in an oath and contract never to part. We will spare a dissertation on chaos; we will not speak of matter and inertia; but as our greatest and purest fountain of light is the sun, we may be allowed a modest exposition of his philosophical state, as a granite gate to the garden beyond. Ninety-five millions of miles to the north, east, south, or west of us, up or down, as the case may be, stands the molten centre of our system—an orb, whose atoms, turbulent with electricity, gravity, or whatever mechanists please to call the attraction of particle for particle, are forever urging to its centre, forever meeting with repulsions when they slide within the forbidden limits of molecular exclusiveness, and eternally vibrating with a quake and quiver which lights and heats the worlds around. In other words, this agitation is one that, transmitted to an ethereal medium, produces therein corresponding vibrations or waves, which are light and heat.

As sound is the symmetrical aërial motion, if our atmosphere embraced our sun, and extended throughout space, we should perhaps hear in the ambient the fundamental chord, resolvable into the diatonic scale—as we look upon the beam of white which the prism decomposes into the solar spectrum, and in the ghostly watches of the night, we might recognize the 'music of the spheres' as the planets rushed around their airy orbits, with a noise like the 'noise of many waters,' no longer a poetic illusion, but a harmonic fact.

Light, whether white or colored, is transmitted through ether in waves of measurable length: each atom of the medium, when disturbed, moves around its place of rest in an orbit of variable dimension and eccentricity. On the character of the orbit depends the character of the light; and on the velocity of orbit motion, its intensity. Like the gentle pulsations which circle from the point where fell the pebble in the purple lake, come the grateful twilight waves, red with the last kiss of day; like the fierce struggles of the storm-beaten ocean floods come the lightning waves, blazing through the thunder clouds, howling in riven agony: so great is the variety of character in these orbicular disturbances, which, acting upon the optic nerves, produce the sensation of multiform light and color.

Waves of light, like waves of sound, are of different lengths, and while the eye prefers some single waves to others, it recognizes a harmony in certain combinations, which it cannot discover in different ones.

While, however, the constitution of individual eyes acknowledges one color more pleasing than another, there is none, perhaps, which does not prefer the coldest monochromatic to entire absence of color, as in blank white, or to an absolute vacancy of light, as in black.

Sepia pieces are more agreeable than the neatest drawings in China ink, or the most graceful curves done in chalk upon a blackboard. But however the eye may admire a severe and simple unity, it relishes still more a harmonious complexity; and a very mediocre little pensée in water colors, will prove more generally attractive than the monochromatic copies in the Liber Veritatis.

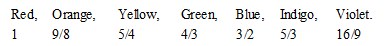

But to this complexity there must be limits—an endless and incongruous variety teases and revolts; the discordant effect of innumerable tints, among which some are sure to be uncongenial to each other, is always extremely irritating. There ought, then, to be a scale of color, it would seem, within whose limits the purest harmonies are to be found, and beyond which subdivisions should be no more allowed than in constant musical notes. When this idea strikes, as it must have, many artists, reason, consideration, instinct, and all, refer at once to the solar spectrum as such an one. The analogy between this scale, which governs the chromatics of the sunset and thunderstorm, and that which the science of man has established, empirically, for harmonies, is remarkable, and we shall try to make it patent. They are both scales of seven: the tonic, mediant, and dominant, find their types in red, yellow, and blue, while the modifications on which the diatonic scale is constructed, resemble, numerically and esthetically, the well-known variations in the spectrum.

The theory of harmonies in optics is the same as in acoustics, the same as in everything—it is based on simplicity. Those colors, like those notes, the number of whose vibrations or waves in the same time bear some simple ratio to each other, are harmonious; an absolute equality produces unison; and a group of harmonies is melody both in music and in color. At this point we cannot but hint at the analogy already discovered between the elements of music and the elements of form. Angles harmonize in simple analysis, or intricate synthesis, whose circular ratios are simple.

Numerical proportions are the roots of that shaft of harmony which, springing from motion, rises and spreads into the nature around us, which the senses appreciate, the spirit feels, and the reason understands. Beauty is order, and the infinity of the law is testified in the ever-swelling proofs of an unlimited consonance in creation, of which these analogies are the smallest types. But the idea of numerical analogy is not new to our age, now that the atomic theory is established, and people are turned back to the days when the much bescouted alchemist pored with rheumy eyes over the crucible, about to be the tomb of elective affinity, and whence a golden angel was to develop from a leaden saint: when they are reminded of the Pythagorean numbers, and the arithmetic of the realists of old, they may very well imagine that the vain world, like an empty fashion, has cycled around to some primitive phase, and look for the door of that academy 'where none could enter but those who understood geometry.'

But to return. When the ear accepts a tone, or the eye a single color, it is noticed that these organs, satiated finally with the sterile simplicity, echo, as it were, in a soliloquizing manner, to themselves, other notes or tints, which are the complementary or harmony-completing ones: so that if nature does not at once present a satisfaction, the organization of the senses allows them internal resources whereon to retreat. 'There is a world without, and a world within,' which may be called complementary worlds. But nature is ever liberal, and her chords are generally harmonies, or exquisite modifications of concord. The chord of the tonic, in music, is the primal type of this harmony in sound; it is perfectly satisfactory to the tympanum; and the ear, knowing no further elements (for the tonic chord combines them all), can ask for nothing more.

This chord, constructed on the tonic C, or Do, as a key note, and consisting of the 1st, 3d, and 5th of the diatonic scale, or Do, Mi, Sol, is called the fundamental chord. The harmony in color which corresponds to this, and leaves nothing for the eye to desire, is, of course, the light that nature is full of—sunlight. White light is then the fundamental chord of color, and it is constructed on the red as the tonic, consisting of red, yellow, and blue, the 1st, 3d, and 5th of the solar spectrum.

This little analogy is suggestive, but its development is striking.

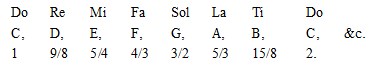

The diatonic scale in music, determined by calculation and actual experiment on vibrating chords, stands as follows. It will be easily understood by musicians, and its discussion appears in most treatises on acoustics:

The intervals, or relative pitches of the notes to the tonic C, appear expressed in the fractions, which are determined by assuming the wave length or amount of vibration of C as unity, and finding the ratio of the wave length of any other note to it. The value of an interval is therefore found by dividing the wave length of the graver by that of the acuter note, or the number of vibrations of the acuter in a given time by the corresponding number of the graver. These fractions, it is seen, comprise the simplest ratios between the whole numbers 1 and 2, so that in this scale are the simple and satisfactory elements of harmony in music, and everybody knows that it is used as such. Now nature exposes to us a scale of color to which we have adverted; it is thus:

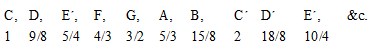

Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, VioletLet us investigate this, and see if her science is as good as mortal penetration; let us see if she too has hit upon the simplest fractions between 1 and 2, for a scale of 7. We can determine the relative pitch of any member of this scale to another, easily, as the wave lengths of all are known from experiment.

The waves of red are the longest; it corresponds, then, to the tonic. Let us assume it as unity, and deduce the pitch of orange by dividing the first by the second.

The length of a red wave is 0.0000266 inches; the length of an orange wave is 0.0000240 inches; the fraction required then is 266/240; dividing both members of this expression by 30, it reduces to 9/8, almost exactly. This is encouraging. We find a remarkable coincidence in ratio, and in elements which occupy the same place on the corresponding scales. Again, the length of a yellow wave is 0.0000227 inches; its pitch on the scale is therefore 266/227; dividing both terms by 55, the reduced fraction approximates to 5/4 with great accuracy, when we consider the deviations from truth liable to occur in the delicate measurements necessary to determine the length of a light vibration, or the amount of quiver in a tense cord. A green wave is 0.0000211 inches in length; its pitch is then 266/211, which reduced, becomes 4/3; in like manner the subsequent intervals may be determined, which all prove to be complete analogues, except, perhaps, violet, whose fraction is 266/167, which reduces nearer 16/9 than 15/8. But these small discrepancies, which might be expected in the results of physical measurements, do not cripple the analogy which appears now in the two following scales:

DIATONIC OR NATURAL SCALE OF MUSIC

Thus orange is to red what D is to C; and to resume the proportion we used before, red is to eye as C is to ear; yellow: eye: Mi: ear; and so on the proportion extends, till the analogy embraces chords, harmonies, melodies, and compositions even.

We have already mentioned the chord of the tonic, and the corresponding eye-music, red, yellow, and blue; let us consider the chord of the dominant or 5th note, whose analogue is blue. This chord is constructed on the 5th of the diatonic as a fundamental note, and consists of the 5th, 7th, and 9th, or returning the 9th an octave, the 5th, 7th, and 2d. The parallel harmony among the spectral colors is blue, violet, and orange. The name 'dominant' indicates the nature of this chord; its often recurring importance in harmonic combinations of a certain key make it easily recognized, and it is even more pleasing than the tonic in its subdued character.