полная версия

полная версияThe Continental Monthly , Vol. 2 No. 5, November 1862

Mr. Walker's bill granted a homestead of a quarter section to every settler on payment of twenty dollars, after three years' occupancy and possession.

The special committee, to which this bill was referred, would not go so far, but authorized Mr. Walker to report 'A bill to arrest monopolies of the public lands and purchases thereof for speculation, and substitute sales to actual settlers only, in limited quantities, and at reduced prices,' &c. This report will be found in vol. 5, Sen. Doc., 1st session, 24th Congress, No. 402. 'In Senate of the United States, June 15, 1836, Mr. Walker made the following report:'

Extracts.—'The committee have adopted the principle that the public lands should be held as a sacred reserve for the cultivators of the soil; that monopolies by individuals or companies should be prevented; that sales should be made only in limited quantities to actual settlers, and the price in their favor reduced and graduated.' * * The old system 'is throwing the public domain into the hands of speculating monopolists. It is reviving many of the evils of the old feudal system of Europe. Under that system, the lands were owned in vast bodies by a few wealthy barons, and leased by them to an impoverished and dependent tenantry.'

A bill based on this principle, and reported by Mr. Walker at a succeeding session, passed the Senate, but was defeated in the House. In each of his annual reports as Secretary of the Treasury, Mr. Walker strongly recommended the homestead policy, which encountered the continual opposition of Mr. Calhoun.

In his inaugural address as Governor of Kansas, of the 27th May, 1857, Mr. Walker thus strongly advocated the Homestead policy:

'If my will could have prevailed as regards the public lands, as indicated in my public career, and especially in the bill presented by me, as chairman of the Committee on Public Lands, to the Senate of the United States, which passed that body but failed in the House, I would authorize no sales of these lands except for settlement and cultivation, reserving not merely a preëmption, but a Homestead of a quarter section of land in favor of every actual settler, whether coming from other States or emigrating from Europe. Great and populous States would thus be added to the Confederacy, until we should soon have one unbroken line of States, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, giving immense additional power and security to the Union, and facilitating intercourse between all its parts. This would be alike beneficial to the old and to the new States. To the working men of the old States, as well as of the new, it would be of incalculable advantage, not merely by affording them a home in the West, but by maintaining the wages of labor, by enabling the working classes to emigrate and become cultivators of the soil, when the rewards of daily toil should sink below a fair remuneration. Every new State, beside, adds to the customers of the old States, consuming their manufactures, employing their merchants, giving business to their vessels and canals, their railroads and cities, and a powerful impulse to their industry and prosperity. Indeed, it is the growth of the mighty West which has added, more than all other causes combined, to the power and prosperity of the whole country; whilst, at the same time, through the channels of business and commerce, it has been building up immense cities in the Eastern Atlantic and Middle States, and replenishing the Federal treasury with large payments from the settlers upon the public lands, rendered of real value only by their labor, and thus, from increased exports, bringing back augmented imports, and soon largely increasing the revenue of the Government from that source also.'—See Doc. Vol. I., No. 8, 1st Sess. XXXVth Congress.

It will no doubt be remembered how much this address was denounced by the secession leaders, and with what fury Mr. Walker was assailed by them for insisting on the rejection of the Lecompton Constitution, by which, it was attempted, by fraud and forgery, to force slavery upon Kansas, against the will of the people.

In June, 1860, a Homestead bill was passed by Congress, securing to actual settlers a quarter section of the public lands, at twenty-five cents per acre, which was vetoed by Mr. Buchanan. The veto message says: 'The Secretary of the Interior estimated the revenue from the public lands for the nest fiscal year at $4,000,000, on the presumption that the present land system would remain unchanged. Should this bill become a law, he does not believe that $1,000,000 will be derived from this source.' It would thus seem that Jacob Thompson, then Secretary of the Interior, was permitted to dictate the financial portion of this veto. He is now in the traitor army; but before leaving the Cabinet, he communicated to the enemy at Charleston important information he had received officially and confidentially. Whilst still Secretary, he was permitted by Mr. Buchanan to accept from Mississippi, after she had seceded, the post of her ambassador to North Carolina, to induce her to secede; which public mission he openly fulfilled, still remaining a member of the Cabinet. Such was the abyss of degradation to which the late Administration had then fallen. Indeed, Thompson (like Floyd and Cobb), was never dismissed by Mr. Buchanan, but resigned his office, receiving then, after all these treasonable and perfidious acts, a most complimentary letter from the late President.

Mr. Thompson's financial argument against the Homestead bill is most fallacious. Our national wealth, by the last census, was $16,159,616,068, and its increase during the last ten years $8,925,481,011, or 126.45 per cent. Now if, as a consequence of the Homestead bill, there should be occupied, improved, and cultivated, during the next ten years, 50,000 additional farms by settlers, or only 5,000 per annum, it would make an aggregate of 8,000,000 acres. If, including houses, fences, barns, and other improvements, we should value each of these farms at ten dollars an acre, it would make an aggregate of $80,000,000. But if we add the products of these farms, allowing only one half of each (80 acres) to be cultivated, and the average annual value of the crops, stock included, to be only ten dollars per acre, it would give $40,000,000 a year, and, in ten years, $400,000,000, independent of the reinvestment of capital. It is clear that, thus, vast additional employment would be given to labor, freight to steamers, railroads, and canals, and markets for manufactures.

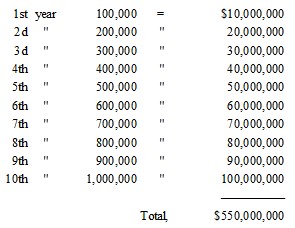

The homestead privilege will largely increase immigration. Now, beside the money brought here by immigrants, the census proves that the average annual value of the labor of Massachusetts per capita was, in 1860, $220 for each man, woman, and child, independent of the gains of commerce—very large, but not given. Assuming that of the immigrants at an average annual value of only $100 each, or less than 33 cents a day, it would make, in ten years, at the rate of 100,000 each year, the following aggregate:

In this table, the labor of all immigrants each year is properly added to those arriving the succeeding year, so as to make the aggregate, the last year, one million. This would make the value of the labor of this million of immigrants, in ten years, $550,000,000, independent of the annual accumulation of capital, and the labor of the children of the immigrants after the first ten years, which, with their descendants, would go on constantly increasing.

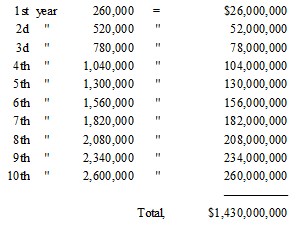

But, by the actual official returns (see page 14 of Census), the number of alien immigrants to the United States, from December, 1850, to December, 1860, was 2,598,216, or an annual average of 259,821, say 260,000. The effect, then, of this immigration, on the basis of the last table, upon the increase of national wealth, was as follows:

Thus the value of the labor of the immigrants from 1850 to 1860, was fourteen hundred and thirty millions of dollars, making no allowance for the accumulation of capital by annual reinvestment, nor for the natural increase of population, amounting by the census in ten years to about twenty-four per cent. This addition to our wealth by the labor of the children, in the first ten years, would be small; but in the second, and each succeeding decennium, when we count children and their descendants, it would be large and constantly augmenting. But the census shows, that our wealth increases each ten years at the rate of 126.45 per cent. Now then, take our increase of wealth in consequence of immigration as before stated, and compound it at the rate of 126.45 per cent, every ten years, and the result is largely over three billions of dollars in 1870, and over seven billions of dollars in 1880, independent of the effect of any immigration succeeding 1860. If these results are astonishing, we must remember that immigration here is augmented population, and that it is population and labor that create wealth. Capital, indeed, is but the accumulation of labor. Immigration, then, from 1850 to 1860, added to our national wealth a sum more than double our whole debt on the first of July last, and augmenting in a ratio much more rapid than its increase, and thus enabling us to bear the war expenses.

As the homestead privilege must largely increase immigration, and add especially to the cultivation of our soil, it will contribute more than any other measure to increase our population, wealth, and power, augment our revenue from duties and taxes, and soon enable us to repeal the tax bill, or, at least, confine it to a few articles of luxury.

Nor has this immigration merely increased our wealth; but it has filled our army with brave volunteer soldiers, Irish, Germans, and of other nationalities, who, side by side with our native sons, are now pouring out their blood on every battle field in defence of our flag and Union. Thousands of them have suffered in rebel dungeons, where many are still languishing—thousands are wounded, disabled for life, or filling a soldier's grave.

Thus has the immigrant proved himself worthy to participate with our native sons in the homestead privilege. He fights our battle, and dies, that the Union may live.

Come, then, our European brother, and enjoy with us every privilege of an American citizen. The altar of freedom is consecrated by the sacrament of our commingled blood. Countrymen of Lafayette and Montgomery, of Steuben and DeKalb, of Koscinsko and Pulaski! you are fighting, like them, in the same great cause, under the same banner, and for the same glorious Union, and, like them, you will reap an immortality of glory, and the gratitude of our country and of mankind. As century shall follow century, in marking this crisis of human destiny, history will record the stupendous fact, that the blood of all Europe commingled freely with our own in the mighty contest, the pledges of the freedom and brotherhood of man!

We have seen that the Homestead bill was of Union origin, opposed by Mr. Calhoun and the pro-slavery party. We have seen that the bill was vetoed by Mr. Buchanan, quoting the opposing argument of a traitor member of his Cabinet, now in the rebel army. The vote in the Senate after the veto, was, yeas 28 (not two thirds), and nays 18. (Sen. Journal, 757, June 23, 1860.) Of the yeas, all but three were from the free States; and of the nays, all were from the slave States. The opposition, then, as foreshadowed by Mr. Calhoun in 1836, was exclusively sectional and pro-slavery. As Mr. Buchanan changed his policy as to Kansas upon the threats of the secession leaders in 1857, so he sacrificed upon their mandate the Homestead bill in 1860.

Most of the eighteen Southern Senators who voted against this bill, are now in the rebel service. Among these eighteen nays, are Jefferson Davis, Bragg, Mason, Hunter, Mallory, Chesnut, Yulee, Wigfall, Fitzpatrick, Iveson, Johnson of Arkansas, Hemphill, and Sebastian. Now, then, when Irish and Germans in the South are asked to fight for the pro-slavery rebellion, let them remember that the secession leaders voted unanimously against the homestead bill, whilst the North then gave its entire vote in, favor of the measure, and have now made it the law of the land.

As it is a blessed thing for the poor and landless to receive, substantially as a gift, a farm from the Government, where they and their children may till their own soil, and enjoy competence, freedom, and free schools, let them never forget, that this was the act of the North, and opposed by the South. If the rebels succeed, they will hold the public domain in their States and Territories for large plantations, to be cultivated by slaves, and sink their 'poor whites,' as nearly as practicable, to the level of their slaves, in accordance with their theory, that capital should own labor.

Texas, is very nearly six times as large as New York, and more than one half the area is public domain of the State, with a most salubrious climate, with all the products of the North and South, as shown by the census, and with three times as many cattle (2,733,267) as in any other State. This vast domain, if the South succeeds, will be cultivated in large tracts by slaves; but with our success, the State title will be forfeited to the Government, and the land colonized by loyal freemen, and subjected to the Homestead law, so that educated free white labor can raise there sugar, cotton, rice, tobacco, and indigo, as well as the crops of the North. It appears by the history of the reign of Henry II., that Ireland (in the year 1102) was the first country which abolished slavery, England still retaining it for many centuries; and Germany scarcely participated in the African slave trade. And now those two brave and mighty races, the Celtic and Teutonic, so devoted to liberty and the rights of man, will never erect the temple of their faith upon the Confederate corner stone, the ownership, of man by man, and of labor by capital. No—they are fighting in the great cause, (now, henceforth, and forever inseparable,) of Liberty and Union. And when, as the result of this rebellion, slavery shall disappear from our country, the words of the Sermon on the Mount, announcing the brotherhood of man, and adopted by our fathers in the Declaration of American Independence, may be inscribed on our banner, 'that all men are created Equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with inalienable Rights; that among these are life, LIBERTY, and the pursuit of happiness.' Such was the faith plighted to God, our country, and humanity, on the day of the nation's birth; in crushing this rebellion, and inaugurating the reign of universal freedom, we are now fulfilling that pledge. Slavery having struck down our flag, having dissevered our States, having, with sacrilegious steps, entered our holy temples, separated churches, and erected a government based on dehumanizing man, under the Union as it was: liberty will reunite us by fraternal and indissoluble ties, under the Union as it will be.

LITERARY NOTICES

The Patience of Hope. By the Author of A Present Heaven. With an Introduction by John G. Whittier, 'Et teneo et teneor.' Boston: Ticknor & Fields.

A work less remarkable for talent than for tender, pious feeling—less marked by genius than goodness, yet of a kind which the impartial critic will still sincerely commend, simply because its defects are negative while its merits are positive and apparent to all who will read only a few pages in it. The author seems to us as one who has gleaned the best from mystical Christianity or Quietism, without having taken up its defects—one who has found in Tauler or Guyon, or perhaps still more in Fénélon, something to love, and has loved it without effort. We are certain that the work is one which will enjoy a very extensive popularity among all liberal-minded yet truly devout Christians.

History of Friedrich the Second, called Frederick the Great. By Thomas Carlyle. In four volumes. Vol. III. New York: Harper & Brothers. Boston: A.K. Loring. 1862.

To judge Carlyle well, one should have outgrown a love for him. Then, and not till then, will the reader ace him as he is—a genius obscured and belittled by eccentricity in judgment and grotesqueness in literary art; a man who must be seen, out of whom much may be taken, but not with profit unless we leave much behind; a writer who was ahead of his age in 1830, but who is wellnigh thirty years behind it now; one still worshipping heroes, and quite ignorant that great ideas are taking for the world the place of great men. It is curious to consider that Carlyle, without understanding the first principles of the French Revolution, should have written most readably on it, and that, still more blind to the manifest path of free labor and of utility, he should still have assumed a pseudo-radical position. Yet, after all, nothing is strange when a man is wrong in his premises. Carp at them as he may, Carlyle is of the destructives rather than the builders, and, like all literary destructives, continually flies for shelter to the conservatives, even as Rabelais fled for safety to the Pope.

In this third volume of Friedrich the Second, he who neither overrates nor underrates Carlyle may read with great profit. In it one sees, as in a brilliant series of highly-colored views—overcolored very often—shifting with strange rapidity and in wild lights, how from June, 1740, to August, 1744, King Frederick lived his own life, and incidentally that of Prussia and a good part of the civilized world with it, as all active and earnest monarchs are wont to do. That it is piquant and interesting—to the well-educated taste more so than any novel—is true enough; and if the author acts despotically and talks arbitrarily, we may smile, and leave him to settle it with his dead men. He must be dumb indeed who can read it and not feel his thinking powers greatly stimulated, and with it, if he be a writer, his faculty of creating.

Jenkins's Vest-Pocket Lexicon. BY Jabez Jenkins. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. Boston: A.K. Loring. 1862.

A dictionary is generally referred to for unfamiliar—not for well-known words; but it is in large and copious ones only that such words are given, and every one has not always at hand his Webster and Worcester 'unabridged.' In view of this want, Jabez Jenkins has compiled an admirable little two-and-a-half-inch square English 'Lexicon of all except familiar words, including the principal scientific and technical terms, and foreign moneys, weights, and measures.' The common Latin and French phrases of two and three words, and the principal names of classical mythology, are also given; 'omitting,' says J.J., 'what everybody knows, and containing what everybody wants to know, and cannot readily find.' It would be difficult to exaggerate the great practical utility of this admirable little book, in which, we have, so to speak, the very quintessence of a dictionary given in poco. We should not have looked for a joke, however, in an abridged dictionary—but there is one. 'This Lexicon,' says its author, 'will be found a convenient, and, it is hoped, a valuable vade mecum; and, though not inspiring the same degree of veneration as some of its leviathan contemporaries, may possibly occupy a place much nearer the heart, viz., in the heart-pocket.' Let us not forget, by the way, to mention that S. Austin Allibone has indorsed this little work as one of the most important and useful publications of the day.

Inside Out. A Curious Book by a Singular Man. New York: Miller, Mathews & Clasback, 767 Broadway. Boston; A.K. Loring.

The first instalment of the promised oddity of this work occurs in the first page—in fact, several pages before it—in the assertion that 'this work is respectfully dedicated to the first young lady who can truthfully assert that she has read from title page to colophon WITHOUT SKIPPING. Such is the determination of the author.'

It is needless to say that the determined author has hit upon a tolerably effectual means of securing a few lady readers. As for the work itself, it is, with more eccentricity of thought and less familiarity with composition than we should anticipate in a bad one. It is bold, rather sensational, involving a high-pressure murder and the somewhat connu father-in-difficulties with a daughter, but interesting, and on the whole likely enough—in New York, where any amount of anything may be supposed to take place at any time without in the slightest degree violating the conditions of probability. For his bete noir or grand villain, the Singular Man seems to have studied very carefully the gentleman who is said to have poséd for 'Dens-death' in 'Cecil Dreeme,' and has to our mind approached him more closely even than Winthrop has done. Among the characters one—'Charles Tewphunny'—strikes us as a reality; a vigorous, earnest, cheerful nature, clear and fine even through the obscurity and occasional crudity of his word-painter. We like Charles—he should have been the favored one by love, as he is in being the true hero of the tale.

The work is in fact crude, as though hastily written and had not been at all reviewed—at least by an experienced writer. On the other hand, its author is evidently a gentleman, one widely familiar with life—even a town life in many details—and is most unmistakably a scholar of rare ripeness. So manifest is his ability, and so remarkable the varied learning and experience which gleam (unknown to the author himself) through many unconscious allusions, that we wonder at finding such peculiar gifts turned to illustrate a tale, above all one so carelessly constructed as this is. We find fault with the names: 'Malfaire,' 'Tewphunny,' 'Mrs. Kairfull,' are not well devised; and yet again we at once regret all harsher judgment in some truly human, refined, and delicate passage, which is as creditable to the author's taste as heart. Taking it altogether, 'Inside Out' is, according to promise, a very curious book indeed. In justice to the publishers, we must say a word in favor of its neat binding and very attractive typography.

Country Living and Country Thinking. By Gail Hamilton. Boston: Ticknor & Fields. 1862.

The Essay, after long years of sleep, has sprung up of late to, at least, popularity, and from the pens of the Country Parson and his disciples has sent word-pictures and personal experiences well through the country. Among the most promising of the American members of the 'Parson's' flock is Gail Hamilton, a lively, well-writing, intensely-Yankee woman; that is to say, a bird who would fly far and fast indeed were she not well bound down by Puritanical chains, and who, in default of other experience-means of expression, clinks her fetters in measures which are merry enough for the many, albeit somewhat sorrowful at times to those who feel how much more she might have done under more genial influences and in a freer field. We could also wish a little less of the endless I and Me and Mine of the Essays, and wonder if the author will never tire of her intense self-setting forth. But this is the constant fault of the personal essay, let who will write it; and since it has great names to sanction it, we may perhaps let it pass.

EDITOR'S TABLE

The President's Proclamation is based mainly on the act of Congress to which he refers. That act was passed with great approach to unanimity among unconditional Unionists, and met their approbation throughout the country. That the rebel States, as a military question, must be deprived of the 'sinews of war,' which, with them, are the sinews of slaves, is quite certain. They have boasted, as well before as since the rebellion, that their great strength in war consisted in their ability to send all the whites to battle, whilst the slaves were retained at home to cultivate the lands and provide subsistence for armies. Take from the South its slaves, and the necessary supplies must cease for want of laborers in the field, or the whites must be withdrawn from the armies to raise provisions. In either event, the rebellion must terminate in defeat. There are thousands then, who, under ordinary circumstances, would oppose emancipation, yet who will support this measure as a military necessity. As regards the Border States, the President still adheres to his original programme: emancipation with their consent, compensation by Congress, and colonization beyond our limits.