полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 5, 1920

The attitude of the Negro immediately after the war was that of opposition to all kinds of labor. He had not as then learned the distinction between working as a slave and working as a freedman. What he wanted most was an education, a literary education, such as the white man had. He did not want his education for any definite purpose, except as an end in itself. The chief reason probably may have been that of a desire to put himself on a par with the white man, and to prove his intellectual equality. The attitude to-day is radically different, being represented by men like Washington and DuBois. Washington preached the gospel of industrial education, believing strongly that that method would lead to an increase of the economic wealth of the race, whereby they could acquire the so-called higher education. DuBois, however, although he believed in the efficiency of industrial training, also felt that the race should not neglect to educate leaders even at the present time, so that his attitude differs from that of Washington in a slight degree. Two short quotations from Washington's writings may illustrate to a certain extent the attitude of the leaders of Negro education: "What Negro education needed most," said he, "was not so much more schools or different kinds of schools, as an educational policy and a school system,60 and "I want to see education as common as grass, and as free for all as sunshine and rain.61

Prejudice is an important factor in the attitude of the white race toward Negro education. This prejudice seems to be in all sections of the country, but it is the southerner who is heard from the most, possibly because he is more in contact with the real problem and then because it seems to be a policy of southern politicians to attempt to outdo each other in their speeches along the line of race prejudice. According to Weatherford prejudice has arisen out of the fear that education will lead to the dominance of the Negro in politics and to promiscuous mingling in social life. "The southern white man will never be enthusiastic for Negro education, until he is convinced that such education will not lead to either of these."62 This feeling of a group is expressed in the following statement in a report to the Baltimore Council by a committee in 1913: "No fault is found with the Negroes' ambitions," said the report, "but the Committee feels that Baltimoreans will be criminally negligent as to their future happiness, if they suffer the Negroes' ambitions to go unchecked."63 Mr. Thomas Dixon, Junior, deplores the fact that Washington was training the Negroes to be "masters of men," stating that "if there is one thing the southern white man cannot endure it is an educated Negro."64

School officials and educators on the other hand show an entirely different attitude. Mr. Glenn, recently Superintendent of Education of Georgia, made the declaration that "The Negro is … teachable and susceptible to the same kind of mental improvement characteristic to any other race."65 Thomas Nelson Page states that "the Negro may individually attain a fair and in uncommon instances a considerable degree of mental development."66 Another states that "We must educate him because ignorant men are dangerous, especially to a democracy pledged to educate all men."67 Some believe that we must also educate him for self-protection from vice and disease. The Southern Educational Association in 1907 passed the following resolution: "We endorse the accepted policy of the States of the South in providing educational facilities for the youth of the Negro race, believing that whatever the ultimate solution of this grievous problem may be, education must be an important factor in that solution."68

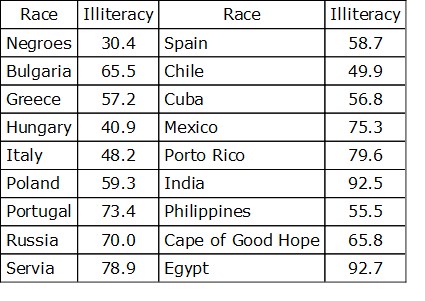

Illiteracy which in 1863 equaled about 95 per cent of the Negro population has been decreasing rapidly since the Civil War. The illiteracy of the Negro during the last three decades has been as follows: in 1890, 57.1 per cent; in 1900, 44.5 per cent; and in 1910, 30.4 per cent. In the North in 1910 the illiteracy was 18.2 per cent in the South 48.0 per cent, and in the West 13.1 per cent.69 The urban Negro in 1910 showed 17.6 per cent illiteracy and the rural 36.5 per cent. Louisiana showed 48 per cent, whereas Minnesota and Oregon showed only 3.4 per cent.70 In 1900 when the Negro illiteracy was 44.5 per cent, the children between ten and twenty-five years of age showed only 30 per cent and those between 10 and 14 years in Mississippi showed only 22 per cent.71 The illiteracy for all Negro children was 25 per cent, whereas the illiteracy for all white children was only 10.5 per cent.72 The illiteracy of our Negroes does not seem so great when a comparison is made with some foreign countries:73

The percentage of Negro illiteracy in America is less than any one of these foreign races.

The criminality of the Negro seemingly has decreased as the illiteracy has decreased. Out of every 100 criminals only 39 could read and 61 could not, whereas in the general population 43 could read and 57 could not.74 In the Mississippi penitentiary where they had 450 convicts of Negro blood one half of them could neither read nor write, and less than 10 per cent had anything like a fair education.75 Atlanta University has graduated 800 Negro men and women, not one of whom has ever been convicted of crime. Fisk University has only one graduate who has ever been convicted. Greensboro Agricultural and Technical College has had 2,000 students since its establishment, and only five have ever been convicted of crime. Two of these had been expelled students, and none were among the three hundred graduates of the college. Negro students who have gone to high school show a remarkably low percentage of crime. Of the 200 graduates from the Winston-Salem High School (North Carolina) only one has a criminal record. Waters Normal Institute at Winton, North Carolina, has graduated more than 130 students and not one of these has ever been arrested or convicted of any crime.76 The records of the southern prisons show that at least 90 per cent of those in prison are without trades of any sort.77 According to Booker T. Washington, "Manual training is as good a prevention of criminality as vaccination is of smallpox."78 In 1903, in Gloucester County, Virginia, twenty-five years after education had been introduced, there were 30 arrests for misdemeanors, 16 white and 14 black; and in the next year there were 15 arrests for misdemeanors, 14 white and one black.79 The general opinion of the southerner may be judged by the answers to a questionnaire sent out to prominent southern men in each of the Southern States. To the question "Does crime grow less as education increases?" there were 102, answered "yes" and 19 answered "no."80

One of the charges against the Negro has been his shiftlessness, both as far as his personal industriousness is concerned, and as far as the care of his home and things about him. Now, however, education has increased his standards and his wants, so that since he desires to have land, homes, churches, books, papers, and education for his children, he will labor regularly and efficiently to supply these. The graduates of Tuskegee Institute are kept in touch with by one of the school officials, who reported that not 10 per cent could be found in idleness and that only one was in a penitentiary.81

Loretta FunkeTHE NEGRO MIGRATION TO CANADA AFTER THE PASSING OF THE FUGITIVE SLAVE ACT

When President Fillmore signed the Fugitive Slave Bill82 on September 18, 1850, he started a Negro migration that continued up to the opening of the Civil War, resulting in thousands of people of color crossing over into Canada and causing many thousands more to move from one State into another seeking safety from their pursuers. While the free Negro population of the North increased by nearly 30,000 in the decade after 1850, the gain was chiefly in three States, Ohio, Michigan and Illinois. Connecticut had fewer free people of color in 1860 than in 1850 and there were half a dozen other States that barely held their own during the period. The three States showing gains were those bordering on Canada where the runaway slave or the free man of color in danger could flee when threatened. It is estimated that from fifteen to twenty thousand Negroes entered Canada between 1850 and 1860, increasing the Negro population of the British provinces from about 40,000 to nearly 60,000. The greater part of the refugee population settled in the southwestern part of the present province of Ontario, chiefly in what now comprises the counties of Essex and Kent, bordering on the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair. This large migration of an alien race into a country more sparsely settled than any of the Northern States might have been expected to cause trouble, but records show that the Canadians received the refugees with kindness and gave them what help they could.83 At the close of the Civil War many of the Negroes in exile returned, thus relieving the situation in Canada.

The Fugitive Slave Bill had been signed but a month when Garrison pointed out in The Liberator that a northward trek of free people of color was already under way. "Alarmed at the operation of the new Fugitive Slave Law, the fugitives from slavery are pressing northward. Many have been obliged to flee precipitately leaving behind them all the little they have acquired since they escaped from slavery."84 The American Anti-Slavery Society's report also notes the consternation into which the Negro population was thrown by the new legislation85 and from many other contemporary sources there may be obtained information showing the distressing results that followed immediately upon the signing of the bill. Reports of the large number of new arrivals were soon coming from Canada. Hiram Wilson, a missionary at St. Catharines, writing in The Liberator of December 13, 1850, says: "Probably not less than 3,000 have taken refuge in this country since the first of September. Only for the attitude of the north there would have been thousands more." He says that his church is thronged with fugitives and that what is true of his own district is true also of other parts of southern Ontario. Henry Bibb, in his paper The Voice of the Fugitive86 published frequent reports of the number of fugitives arriving at Sandwich on the Detroit River. In the issue of December 3,1851, he reports 17 arrivals in a week. On April 22, 1852, he records 15 arrivals within the last few days and notes that "the Underground Railroad is doing good business this spring." On May 20, 1852, he reports "quite an accession of refugees to our numbers during the last two weeks" and on June 17 notes the visit of agents from Chester, Pennsylvania, preparatory to the movement of a large number of people of color from that place to Canada. On the same date he says: "Numbers of free persons of color are arriving in Canada from Pennsylvania and the District of Columbia, Ohio and Indiana. Sixteen passed by Windsor on the seventh and 20 on the eighth and the cry is 'Still they come.'" The immigration was increasing week by week, for on July 1 it was reported in The Voice of the Fugitive that "in a single day last week there were not less than 65 colored emigrants landed at this place from the south.... As far as we can learn not less than 200 have arrived within our vicinity since last issue." Almost every number of the paper during 1852 gives figures as to the arrivals of the refugees. On September 23 Bibb reported the arrival of three of his own brothers while on November 4, 1852, there is recorded the arrival of 23 men, women and children in 48 hours. Writing to The Liberator of November 12, 1852, Mary E. Bibb said that during the last ten days they had sheltered 23 arrivals in their own home. The American Missionary Association, which had workers among the fugitives in Canada noted in its annual report for 1852 that there had been a large increase of the Negro population during the year87 while further testimony to the great activity along the border is given by the statement that the Vigilance Committee at Detroit assisted 1,200 refugees in one year and that the Cleveland Vigilance Committee had a record of assisting more than a hundred a month to freedom.88

The northern newspapers of the period supply abundant information regarding the consternation into which the Negroes were thrown and their movements to find places of safety. Two weeks after President Fillmore had signed the Fugitive Slave Bill a Pittsburgh despatch to The Liberator stated that "nearly all the waiters in the hotels have fled to Canada. Sunday 30 fled; on Monday 40; on Tuesday 50; on Wednesday 30 and up to this time the number that has left will not fall short of 300. They went in large bodies, armed with pistols and bowie knives, determined to die rather than be captured."89 A Hartford despatch of October 18, 1850, told of five Negroes leaving that place for Canada;90 Utica reported under date of October 2 that 16 fugitive slaves passed through on a boat the day before, bound for Canada, all well armed and determined to fight to the last;91 The Eastport Sentinel of March 12 noted that a dozen fugitives had touched there on the steamer Admiral, en route to St. John's; The New Bedford Mercury said: "We are pleased to announce that a very large number of fugitive slaves, aided by many of our most wealthy and respected citizens have left for Canada and parts unknown and that many more are on the point of departure."92 The Concord, New Hampshire, Statesman reported: "Last Tuesday seven fugitives from slavery passed through this place … and they probably reached Canada in safety on Wednesday last. Scarcely a day passes but more or less fugitives escape from the land of slavery to the freedom of Canada … via this place over the track of the Northern Railroad."93

Many other examples of the effect of the Fugitive Slave Act might be noted. The Negro population of Columbia, Pennsylvania, dropped from 943 to 487 after the passing of the bill.94 The members of the Negro community near Sandy Lake in northwestern Pennsylvania, many of whom had farms partly paid for, sold out or gave away their property and went in a body to Canada.95 In Boston a fugitive slave congregation under Leonard A. Grimes had a church built when the blow fell. More than forty members fled to Canada.96 Out of one Baptist church in Buffalo more than 130 members fled across the border, a similar migration taking place among the Negro Methodists of the same city though they were more disposed to make a stand. At Rochester all but two of the 114 members of the Negro Baptist church fled, headed by their pastor, while at Detroit the Negro Baptist church lost 84 members, some of whom abandoned their property in haste to get away.97 A letter from William Still, agent of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, to Henry Bibb at Sandwich says there is much talk of emigration to Canada as the best course for the fugitives.98 The Corning Journal illustrates the aid that was given to the fugitives by northern friends. Fifteen fugitives, men, women and children, came in by train and stopped over night. In the morning a number of Corning people assisted them to Dunkirk and sent a committee to arrange for passage to Canada. The captain of the lake steamer upon which they embarked, very obligingly stopped at Fort Maiden, on the Canadian side, for wood and water and the runaways walked ashore to freedom. "The underground railroad is in fine working order," is the comment of The Journal. "Rarely does a collision occur, and once on the track passengers are sent through between sunrise and sunset." That time did not dull the terrors of the Fugitive Slave Act is shown by the fact that every fresh arrest would cause a panic in its neighborhood. At Chicago in 1861, almost on the eve of the Civil War, more than 100 Negroes left on a single train following the arrest of a fugitive, taking nothing with them but the clothes on their backs and most of them leaving good situations behind."99

The Underground Railroad system was never so successful in all its history as after 1850. Despite the law, and the infamous activities of many of the slave-catchers, at least 3,000 fugitives got through to Canada within three months after the bill was signed. This was the estimate of both Henry Bibb and Hiram Wilson and there were probably no men in Canada who were better acquainted with the situation than these two. In The Voice of the Fugitive of November 5, 1851, Bibb reported that "the road is doing better business this fall than usual. The Fugitive Slave Law has given it more vitality, more activity, more passengers and more opposition which invariably accelerates business.... We can run a lot of slaves through from almost any of the bordering slave states into Canada within 48 hours and we defy the slaveholders and their abettors to beat that if they can.... We have just received a fresh lot today and still there is room." The Troy Argus learned from "official sources" in 1859 that the Underground Railroad had been doing an unusually large business that year.100 Bibb's newspaper reports, December 2, 1852, that the underground is working well. "Slaveholders are frequently seen and heard, howling on their track up to the Detroit River's edge but dare not venture over lest the British lion should lay his paw upon their guilty heads." Bibb kept a watchful eye on slave-catchers coming to the Canadian border and occasionally reported their presence in his paper. Underground activity was also noted in The Liberator. "The underground railroad and especially the express train, is doing a good business just now. We have good and competent conductors," was a statement in the issue of October 29, 1852.101

Not all those who fled to Canada left their property behind. The Voice of the Fugitive makes frequent reference to Negroes arriving with plenty of means to take care of themselves. "Men of capital with good property, some of whom are worth thousands, are settling among us from the northern states." says the issue of October 22, 1851, while in the issue of July 1, 1852, it is noted that "22 from Indiana passed through to Amherstburg, with four fine covered waggons and eight horses. A few weeks ago six or eight such teams came from the same state into Canada. The Fugitive Slave Law is driving out brains and money." In a later issue it was stated "we know of several families of free people of color who have moved here from the northern states this summer who have brought with them property to the amount of £30,000."102 Some of these people with property joined the Elgin Association settlement at Buxton, purchasing farms and taking advantage of the opportunities that were provided there for education. A letter to The Voice of the Fugitive from Ezekiel C. Cooper, recently arrived at Buxton, says: "Canada is the place where we have our rights."103 He speaks of having purchased 50 acres of land and praises the school and its teacher at Buxton. Cooper came from Northampton, Massachusetts, driven out by the Fugitive Slave Law. A rather unusual case was that of 12 manumitted slaves who were brought to Canada from the South. They had been bequeathed $1,000 each by their former owner. They all bought homes in the Niagara district.104

While fugitives and free Negroes were being harried in the Northern States slaves continued to run away from their masters and seek liberty. "Slaves are making this a great season for running off to Pennsylvania," said the Cumberland, Virginia, Unionist in 1851.105 "A large number have gone in the last week, most of whom were not recaptured." At the beginning of 1851 The Liberator had a Buffalo despatch to the effect that 87 runaways from the South had passed through to Canada since the passing of the bill the previous September.106 Bibb mentions two runaways from North Carolina who were 101 days reaching Canada.107 The Detroit Free Press reported that 29 runaways crossed to Canada about the end of March, 1859, "the first installment of northern emigration from North Carolina."108 About the same time The Detroit Advertiser announced that "seventy fugitive slaves arrived in Canada by one train from the interior of Tennessee. A week before a company of 12 arrived. At nearly the same time a party of seven and another of five were safely landed on the free soil of Canada, making 94 in all. The underground railroad was never before doing so flourishing a business."109 The New Orleans Commercial Bulletin of December 19, 1860, asserted that 1,500 slaves had escaped annually for the last fifty years, a loss to the South of at least $40,000,000. The American Anti-Slavery Society's twenty-seventh report said "Northward migration from slave land during the last year has fully equalled the average of former years."110

It is interesting to note that several of the most famous cases that arose under the Fugitive Slave Act had their ending in Canada. Shadrack, Anthony Burns, Jerry McHenry, the Parkers, the Lemmon slaves and others found refuge across the border after experiencing the terrors of the Fugitive Slave legislation. The Shadrack incident was one of the earliest to arise under the new law. Shadrack, a Negro employe in a Boston coffee house, was arrested on February 15, 1851, on the charge of having escaped from slavery in the previous May. As the commissioner before whom he was brought was not ready to proceed, the case was adjourned for three days. As Massachusetts had forbidden the use of her jails in fugitive cases Shadrack was detained in the United States court room at the court house. A mob of people of color broke into the building, rescued the prisoner and he escaped to Canada. The rescue caused great excitement at Washington and five of the rescuers were indicted and tried but the jury disagreed. The incident showed that the new law would be enforced with difficulty in Massachusetts in view of the fact that the mob had been supported by a Vigilance Committee of most respectable citizens.111

A few months later, at Syracuse, a respectable man of color named Jerry McHenry was arrested as a fugitive on the complaint of a slaver from Missouri. He made an attempt to escape and failed. The town, however, was crowded with people who had come to a meeting of the County Agricultural Society and to attend the annual convention of the Liberty Party. On the evening of October 1, 1851, a descent was made upon the jail by a party led by Gerrit Smith and Rev. Samuel J. May, both well-known abolitionists. The Negro was rescued, concealed for a few days and then sent on to Canada where he died, at Kingston, in 1853.112

A more tragic incident was that known as the Gorsuch case. A slaver named Gorsuch, with his son and some others, all armed, came to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in search of two fugitives. In a house two miles from Lancaster was a Negro family named Parker and they were besieged by the Gorsuchs. The Negroes blew a horn and brought others to their help. Two Quakers who were present were called upon to render help in arresting the Negroes, as they were required to do under the Act, but they refused to aid. In the fighting that took place the elder Gorsuch was killed and his son wounded. The Negroes escaped to Canada where they spent the winter in Toronto and in the spring joined the Elgin Association settlement at Buxton in Kent county.113

The Anthony Burns case attracted more attention than any other arising in the execution of the Fugitive Slave Law. Burns, who was a fugitive from Virginia living in Boston, betrayed his hiding place in a letter which fell into the hands of a southern slaver and was communicated to a slave hunter. The slaver tried to coax Burns to go back to bondage peaceably but failing in this he had him arrested and brought before a commissioner who, on June 2, 1854, decided that Burns was a fugitive and must be sent back to slavery. Boston showed its feelings on the day that the Negro was removed from jail to be sent South. Stores were closed and draped in black, bells tolled, and across State Street a coffin was suspended bearing the legend The Death of Liberty. The streets were crowded and a large military force, with a field piece in front, furnished escort for the lone black. Hisses and cries of " shame" came from the crowd as the procession passed. Burns was soon released from bondage, Boston people and others subscribing to purchase his liberty. He was brought North, educated and later entered the ministry. For several years he was a missionary at St. Catharines, Canada, and died there in the sixties.114