полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 201, September 3, 1853

13. Savile Street, Hull.

This has long been a puzzle to the Hull antiquaries. I have often inquired of old persons likely to know the origin of such names of places at that sea-port as "The Land of Green Ginger," "Pig Alley," "Mucky-south-end," and "Rotten Herring Staith;" and I have come to the conclusion, that "The Land of Green Ginger" was a very dirty place where horses were kept: a mews, in short, which none of the Muses, not even with Homer as an exponent, could exalt ("Ἔπεα πτεροέντα ἐν ἀθανάτοισι θεοῖσι") into the regions of poesy.

Ginger has been cultivated in this country as a stove exotic for about two hundred and fifty years. In one of the histories of Hull, ginger is supposed to have grown in this street, where, to a recent period, the stables of the George Inn, and those of a person named Foster opposite, occupied the principal portion of the short lane called "Land of Green Ginger." It is hardly possible that the true zingiber can have grown here, even in the manure heaps; but a plant of the same order (Zingiberaceæ) may have been mistaken for it. Some of the old women or marine school-boys of the Trinity House, in the adjoining lane named from that guild, or some druggist, may have dropped, either accidentally or experimentally, a root, if not of the ginger, yet of some kindred plant. The magnificent Fuchsia was first noticed in the possession of a seaman's wife by Fuchs in 1501, a century prior to the introduction of the ginger plant into England.

T. J. Buckton.Birmingham.

PHOTOGRAPHIC CORRESPONDENCE

Stereoscopic Angles.—The discussion in "N. & Q." relative to the best angle for stereoscopic pictures has gone far towards a satisfactory conclusion: there are, however, still a few points which may be beneficially considered.

In the first place, the kind of stereoscope to be used must tend to modify the mental impression; and secondly, the amount of reduction from the size of the original has a considerable influence on the final result.

If in viewing a stereoscopic pair of photographs, they are placed at the same distance from the eyes as the length of the focus of the lens used in producing them, then without doubt the distance between the eyes, viz. about two and a quarter inches, is the best difference between the two points of view to produce a perfectly natural result; and if the points of operation be more distant from one another, as I have before intimated, an effect is produced similar to what would be the case if the pictures were taken from a model of the object instead of the object itself.

When it is intended that the pictures taken are to be viewed by an instrument that requires their distance from the eyes to be less than the focal length of the lens used in their formation, what is the result? Why, that they subtend an angle larger than in nature, and are consequently apparently increased in bulk; and the obvious remedy is to increase the angle between the points of generation in the exact ratio as that by which the visual distance is to be lessened. There is one other consideration to which I would advert, viz. that as we judge of distance, &c. mainly by the degree of convergence of the optic axes of our two eyes, it cannot be so good to arrange the camera with its two positions quite parallel, especially for objects at a short or medium distance, as to let its centre radiate from the principal object to be delineated; and to accomplish this desideratum in the readiest way (for portraits especially), the ingenious contrivance of Mr. Latimer Clark, described in the Journal of the Photographic Society, appears to me the best adapted. It consists of a modification of the old parallel ruler arrangement on which the camera is placed; but one of the sides has an adjustment, so that within certain limits any degree of convergence is attainable. Now in the case of the pictures alluded to by Mr. H. Wilkinson in Vol. viii., p. 181., it is probable they were taken by a camera placed in two positions parallel to one another, and it is quite clear that only a portion of the two pictures could have been really stereoscopic. It is perfectly true that two indifferent negatives will often combine and form one good stereoscopic positive, but this is in consequence of one possessing that in which the other is deficient; and at any rate two good pictures will have a better effect; consequently, it is better that the two views should contain exactly the same range of vision.

Geo. Shadbolt.Protonitrate of Iron.—"Being in the habit of using protonitrate of iron for developing collodion pictures, the following method of preparing that solution suggested itself to me, which appears to possess great advantages:—

Water 1 oz.

Protosulphate of iron 14 grs.

Nitrate of potash 10 grs.

Acetic acid ½ drm.

Nitric acid 2 drops.

In this mixture nitrate of potash is employed to convert the sulphate of iron into nitrate in place of nitrate of baryta in Dr. Diamond's formula, or nitrate of lead as recommended by Mr. Sisson; the advantage being that no filtering is required, as the sulphate of potash (produced by the double decomposition) is soluble in water, and does not interfere with the developing qualities of the solution.

"The above gives the bright deposit of silver so much admired in Dr. Diamond's pictures, and will be found to answer equally well either for positives or negatives. If the nitric acid be omitted, we obtain the effects of protonitrate of iron prepared in the usual way.—John Spiller."

(From the Photographic Journal.)Photographs in natural Colours.—As "N. & Q." numbers among its correspondents many residents in the United States, I hope you will permit me to inquire through its columns whether there is really any foundation for the very startling announcement, in Professor Hunt's Photography, of Mr. Hill of New York having "obtained more than fifty pictures from nature in all the beauty of native coloration," or whether the statement is, as I conclude Professor Hunt is inclined to believe, one of those hoaxes in which many of our transatlantic friends take so much delight.

Matter-of-Fact.Photographs by artificial Lights.—May I ask for references to any manuals of photography, or papers in scientific journals, in which are recorded any experiments that have been made with the view of obtaining photographs by means of artificial lights? This is, I have no doubt, a subject of interest to many who, like myself, are busily occupied during the day, and have only their evenings for scientific pursuits: while it is obvious, that if such a process can be successfully practised, there are many objects—such as prints, coins, seals, objects of natural history and antiquity—which might well be copied by it, even though artificial light should prove far slower in its action than solar light.

A Clerk.Replies to Minor Queries

Vandyke in America (Vol. viii., p. 182.).—I would take the liberty of asking Mr. Balch of Philadelphia whom he means by Col. Hill and Col. Byrd, "worthies famous in English history, and whose portraits by Vandyke are now on the James River?" I know of no Col. Hill or Byrd whom Vandyke could possibly have painted. I should also like to know what proof there is that the pictures, whomsoever they represent, are by Vandyke. Mr. Balch says that he favours us with this information "in answer to the query" (Vol. vii., p. 38.); but I beg leave to observe that it is by no means "in answer to the query," which was about an engraved portrait and not picture, and his thus bringing in the Vandykes à propos de bottes makes me a little curious about their authenticity.

C.Title wanted—Choirochorographia (Vol. viii., p. 151.).—The full title of the book inquired after is as follows:

"Χοιροχωρογραφια: sive, Hoglandiæ Descriptio.—Plaudite Porcelli Porcorum pigra Propago (Eleg. Poet.): Londini, Anno Domini 1709. Pretium 2d," 8vo.

The printer, as appears from the advertisement at the end of the volume, was Henry Hills. The middle of the title-page is occupied by a coarsely executed woodcut, representing a boar with barbed instrument in his snout, and similar instrument on a larger scale under the head, surmounted with some rude characters, which I read

"TURX TRVYE BEVIS O HAMTVN."The dedication is headed, "Augusto admodum & undiquaq; Spectabili Heroi Domini H– S– Maredydius Caduganus Pymlymmonensis, S.P.D." The entire work appears to be written in ridicule of Hampshire, and to be intended as a retaliation for work written by Edward Holdsworth, of Magd. Coll. Oxford, entitled Muscipula, sive καμβρο-μυο-μαχια, published by the same printer in the same year, and translated by Dr. Hoadly in the fifth volume of Dodsley's Miscellany, p. 277., edit. 1782.

Query, Who was the author? and had Holdsworth any farther connexion with Hampshire than that of having been educated at Winchester School?

J. F. M.Second Growth of Grass (Vol. viii., p. 102.).—R. W. F. of Bath inquires for other names than "fog," &c. In Sussex we leave "rowens," or "rewens" (the latter, I believe, a corruption), used for the second growth of grass.

Halliwell, in his Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words, has "Rowens, after-grass," as a Suffolk word. Bailey gives the word, with a somewhat different signification; but he has "Rowen hay, latter hay," as a country word.

William Figg.Lewes.

In Norfolk this is called "aftermath eddish," and "rowans" or "rawins."

The first term is evidently from the A.-S. mæth, mowing or math: Bosworth's Dictionary. Eddish is likewise from the A.-S. edisc, signifying the second growth; it is used by Tusser, October's Husbandry, stanza 4.:

"Where wheat upon eddish ye mind to bestow,Let that be the first of the wheat ye do sow."Rawings also occurs in Tusser, and in the Promptorium Parvulorum, rawynhey is mentioned. In Bailey's Dictionary it is spelt rowen and roughings: this last form gives the etymology, for rowe, as may be seen in Halliwell, is an old form for rough.

E. G. R.I have always heard it called in Northumberland, fog; in Norfolk, after-math; in Oxfordshire, I am told, it is latter-math. This term is pure A.-Saxon, mæth, the mowing; the former word fog, and eddish also, are to be found in dictionaries, but their derivation is not satisfactory.

C. I. R.Snail eating (Vol. viii., p. 34).—The beautiful specimens of the large white snails were brought from Italy by Single-speech Hamilton, a gentleman of vertù and exquisite taste, and placed in the grounds at Paynes Hill, and some fine statues likewise. On the change of property, the snails were dispersed about the country; and many of them were picked up by my grandfather, who lived at the Grove under Boxhill, near Dorking. They were found in the hedges about West Humble, and in the grounds of the Grove. I had this account from my mother; and had once some of the shells, which I had found when staying in Surrey.

Julia R. Bockett.Southcote Lodge.

The snails asked after by Mr. H. T. Riley are to be met with near Dorking. When in that neighbourhood one day in May last, I found two in the hedgerow on the London road (west side) between Dorking and Box Hill. They are much larger than the common snail, the shells of a light brown, and the flesh only slightly tinged with green. I identified them by a description and drawing given in an excellent book for children, the Parent's Cabinet, which also states that they are to be found about Box Hill.

G. Rogers Long.The large white snail (Helix pomatia) is found in abundance about Box Hill in Surrey. It is also plentiful near Stonesfield in Oxfordshire, where have, at different periods, been discovered considerable remains of Roman villas; and it has been suggested that this snail was introduced by the former inhabitants of those villas.

W. C. Trevelyan.Wallington.

Sotades (Vol. vii., p. 417.).—Sotades is the supposed inventor of Palindromic verses (see Mr. Sands' Specimens of Macaronic Poetry, p. 5., 1831. His enigma on "Madam" was written by Miss Ritson of Lowestoft).

S. Z. Z. S.The Letter "h" in "humble" (Vol. viii., p. 54).—The question has been raised by one of your correspondents (and I have not observed any reply thereto), as to whether it is a peculiarity of Londoners to pronounce the h in humble. If, as a Londoner by birth and residence, I might be allowed to answer the Query, I should say that the h is never heard in humble, except when the word is pronounced from the pulpit. I believe it to be one of those, either Oxford or Cambridge, or both, peculiarities, of which no reasonable explanation can be given.

I should be glad to hear whether any satisfactory general rule has been laid down as to when the h should be sounded, and when not. The only rule which occurs to me is to pronounce it in all words coming to us from the Celtic "stock," and to pass it unsounded in those which are of Latin origin. If this rule be admitted, the pronunciation sanctioned by the pulpit and Mr. Dickens is condemned.

Benjamin Dawson.London.

Lord North (Vol. vii., p. 317. Vol. viii., p. 184.).—Is M. E. of Philadelphia laughing at us, when he refers us to a woodcut in some American pictorial publication on the American Revolution for a true portraiture of the figure and features of King George III.; different, I presume, from that which I gave you. His woodcut, he says, is taken "from an English engraving;" he does not tell us who either painter or engraver was—but no matter. We have hundreds of portraits by the best hands which confirm my description, which moreover was the result of personal observation: for, from the twentieth to the thirtieth years of my life, I had frequent and close opportunities of approaching his Majesty. I cannot but express my surprise that "N. & Q." should have given insertion to anything so absurd—to use the gentlest term—as M. E.'s appeal to his "woodcut."

C.Singing Psalms and Politics (Vol. viii., p. 56.).—One instance of the misapplication of psalmody must suggest itself at once to the readers of "N. & Q.," I mean the melancholy episode in the history of the Martyr King, thus related by Hume:

"Another preacher, after reproaching him to his face with his misgovernment, ordered this Psalm to be sung,—

'Why dost thou, tyrant, boast thyself,Thy wicked deeds to praise?'The king stood up, and called for that Psalm which begins with these words,—

'Have mercy, Lord, on me, I pray;For men would me devour.'The good-natured audience, in pity to fallen majesty, showed for once greater deference to the king than to the minister, and sung the psalm which the former had called for."—Hume's History of England, ch. 58.

W. Fraser.Tor-Mohun.

Dimidiation by Impalement (Vol. vii., p. 630.).—Your correspondent D. P. concludes his notice on this subject by doubting if any instance of "Dimidiation by Impalement" can be found since the time of Henry VIII. If he turn to Anderson's Diplomata Scotiæ (p. 164. and 90.), he will find that Mary Queen of Scots bore the arms of France dimidiated with those of Scotland from A.D. 1560 to December 1565. This coat she bore as Queen Dowager of France, from the death of her first husband, the King of France, until her marriage with Darnley.

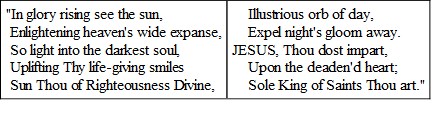

T. H. de H."Inter cuncta micans," &c. (Vol. vi, p. 413.; Vol. vii., p. 510.).—The following translation is by the Rev. Geo. Greig of Kennington. It preserves the acrostic and mesostic, though not the telestic, form of the original:

Hull.

Marriage Service (Vol. viii., p. 150.).—I have seen the Rubric carried out, in this particular, in St. Mary's Church, Kidderminster.

Cuthbert Bede, B. A.Widowed Wife (Vol. viii., p. 56.).—Eur. Hec. 612. "Widowed wife and wedded maid," occurs in Vanda's prophecy; Sir W. Scott's The Betrothed, ch. xv.

S. Z. Z. S.Pure (Vol. viii., p. 125.).—The use of the word pure pointed out by Oxoniensis is nothing new. It is a common provincialism now, and was formerly good English. Here are two examples from Swift (Letters, by Hawkesworth, vol. iv. 1768, p.21.):

"Ballygall will be a pure good place for air."

Ibid. p. 29.:

"Have you smoakt the Tattler yet? It is much liked, and I think it a pure one."

C. Mansfield Ingleby.Birmingham.

"Purely, I thank you," is a common reply of the country folks in this part when accosted as to their health. I recollect once asking a market-woman about her son who had been ill, and received for an answer: "Oh he's quite fierce again, thank you, Sir." Meaning, of course, that he had quite recovered.

Norris Deck.Cambridge.

Mrs. Tighe (Vol. viii., p. 103.).—"There is a likeness of Mrs. Henry Tighe, the authoress of 'Psyche,' in the Ladies' Monthly Museum for February, 1818. It is engraved by J. Hopwood, jun., from a drawing by Miss Emma Drummond. Underneath the engraving referred to, are the words 'Mrs. Henry Tighe;' but she is called in the memoir, 'wife of William Tighe, Esq., M.P. for Wicklow, whose residence is Woodstock, county of Kilkenny, author of The Plants, a poem, 8vo.: published in 1808 and 1811; and Statistical Observations on the County of Kilkenny, 1800. Mrs. Tighe is described as having had a pleasing person, and a countenance that indicated melancholy and deep reflection; was amiable in her domestic relations; had a mind well stored with classic literature; and, with strong feelings and affections, expressed her thoughts with the nicest discrimination, and taste the most refined and delicate. Thus endued, it is to be regretted that Mrs. Tighe should have fallen a victim to a lingering disease of six years at the premature age of thirty-seven, on March 24, 1810.'—The remainder of the short notice does not throw any additional light on Mrs. Tighe, or family; but if you, Sir, or the Editor of "N. & Q." wish, I will cheerfully transcribe it.—I am, Sir, yours in haste,

Vix."Belfast, Aug. 15."

[We are indebted for the above reply to the Dublin Weekly Telegraph, which not only does us the honour to quote very freely from our pages, but always most liberally acknowledges the source from which the articles so quoted are derived.]

Satirical Medal (Vol. viii., p. 57.).—I have seen the same medal of Sir R. Walpole (the latest instance of the mediæval hell-mouth with which I am acquainted) bearing on the obverse—"THE GENEROUSE (sic) DUKE OF ARGYLE;" and at the foot—"NO PENTIONS."

S. Z. Z. S."They shot him dead at the Nine-Stone Rig" (Vol. viii., p. 78.).—Your correspondent the Borderer will find the fragment of the ballad he is in search of commencing with the above line, in the second volume of the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, p. 114. It is entitled "Barthram's Dirge," and "was taken down," says Scott, "by Mr. Surtees, from the recitation of Anne Douglas, an old woman, who weeded his garden."

Since the death of Mr. Surtees, however, it has been ascertained that this ballad, as well as "The Death of Featherstonhaugh," and some others in the same collection, were composed by him and passed off upon Scott as genuine old Scottish ballads.

Farther particulars respecting this clever literary imposition are given in a review of the "Memoir of Robert Surtees," in the Athenæum of August 7, 1852.

J. K. R. W.Hendericus du Booys: Helena Leonora de Sievéri (Vol. v., p. 370.).—Are two different portraits of each of these two persons to be found? By no means. There exists, however, a plate of each, engraved by C. Visscher; but the first impressions bear the address of E. du Booys, the later that of E. Cooper. As I am informed by Mr. Bodel Nijenhuis, Hendericus du Booys took part in the celebrated three-days' fight, Feb. 18, 19, and 20, 1653, between Blake and Tromp.—From the Navorscher.

M.House-marks, &c. (Vol. vii., p. 594. Vol. viii., p. 62.).—May I be allowed to inform Mr. Collyns that the custom he refers to is by no means of modern date. Nearly all the cattle which come to Malta from Barbary to be stall-fed for consumption, or horses to be sold in the garrison, bring with them their distinguishing marks by which they may be easily known.

And it may not be out of place to remark, that being one of a party in the winter of 1830, travelling overland from Smyrna to Ephesus, we reached a place just before sunset where a roving band of Turcomans had encamped for the night. On nearing these people we observed that the women were preparing food for their supper, while the men were employed in branding with a hot iron, under the camel's upper lip, their own peculiar mark,—a very necessary precaution, it must be allowed, with people who are so well known for their pilfering propensities, not only practised on each other, but also on all those who come within their neighbourhood. Having as strangers paid our tribute to their great dexterity in their profession, the circumstance was published at the time, and to this day is not forgotten.

W. W.Malta.

"Qui facit per alium, facit per se."—In Vol. vii., p. 488., I observe an attempt to trace the source of the expression, "Qui facit per alium, facit per se." A few months since I met with the quotation under some such form as "Qui facit per alium, per se facere videtur," in the preface to a book on Surveying, by Fitzherbert (printed by Berthelet about 1535), where it is attributed to St. Augustine. As I know of no copy of the works of that father in these parts (though I heard him quoted last Sunday in the pulpit), I cannot at present verify the reference.

J. Sleednot.Halifax.

Engin-à-verge (Vol. vii., p. 619. Vol. viii., p. 65.).—H. C. K. is mistaken in his conjecture respecting this word, as the following definition of it will show:

"Engins-à-verge. Ils comprenaient les diverges espèces de catapultes, les pierriers, &c."—Bescherelle, Dictionnaire National.

B. H. C.Campvere, Privileges of (Vol viii., p. 89.).—"Jus Gruis liberæ." Does not this mean the privilege of using a crane to raise their goods free of dues, municipal or fiscal? Grus, grue, krahn, kraan, all mean, in their different languages, crane the bird, and crane the machine.

J. H. L.Humbug—Ambages (Vol. viii., p. 64.).—May I be permitted to inform your correspondent that Mr. May was certainly correct when using the word "ambages" as an English word in his translation of Lucan.

In Howell's Dictionary, published in London in May 1660, I find it thus recorded

"Ambages, or circumstances.""Full of ambages."W. W.Malta.

"Going to Old Weston" (Vol. iii., p. 449.).—In turning over the pages of the third volume of "N. & Q." recently, I stumbled on Arun's notice of the above proverb. It immediately struck me that I had heard it used myself a few days before, without being conscious at the time of the similarity of the expression. I was asking an old man, who had been absent from home, where he had been to? His reply was, "To Old Weston, Sir. You know I must go there before I die." Knowing that he had relatives living there, I did not, at the time, notice anything extraordinary in the answer; but, since reading Arun's note, I have made some inquires, and find the saying is a common one on this (the Northamptonshire) side of Old Weston, as well as in Huntingdonshire. I have been unable to obtain any explanation of it, but think the one suggested by your correspondent must be right. One of my informants (an old woman upwards of seventy) told me she had often heard it used, and wondered what could be its meaning, when she was a child.