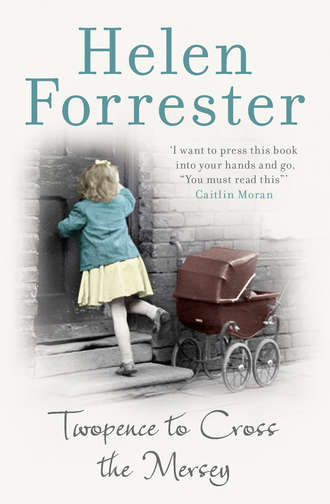

Полная версия

Twopence to Cross the Mersey

‘I can’t help it,’ Father said helplessly. ‘That is what they told me.’

He sat, rubbing his cold hands gently together to restore the circulation, anxiety apparent in every line of him.

‘I must obtain a position. But I don’t even know anybody whom I could ask about a post. I have never lived in Liverpool long enough to make close friends, as you know.’

I remembered that when Mother wanted a servant she used sometimes to advertise in the newspaper, and I suggested that perhaps other posts were advertised also.

This idea was a revelation to Father and he hailed it with delight.

‘By Jove, the girl is right. Look in the newspapers.’

We succeeded in borrowing the landlady’s newspaper, after promising faithfully to return it intact.

And so began an endless writing of replies to advertisements on pennyworths of notepaper. Father did not know that firms frequently got seventy to eighty replies to an advertisement for a clerk, and that they just picked a few envelopes at random from the mighty pile, knowing that almost every applicant would be qualified for the post advertised.

That afternoon, Father undertook another long, cold walk, this time to the south end of the city, to look for accommodation. He had no success and returned hungry and dispirited.

Two days later ‘The Parish’ presented him with thirty-eight shillings, which represented forty-three shillings less five shillings for the food vouchers already supplied.

Only two more days were left of our tenancy of the rooms and our landlady had already reminded us, quite civilly, that she would require the rooms at the end of the week. Mother said, therefore, that she would take the money from ‘The Parish’ and, with the aid of a taxi, go to the south end of the town to see if she could find us a home.

Father protested that she was not fit for the journey, but she insisted coldly that she could manage and, after instructing me to look after baby Edward and Avril, she sent him to arrange for a taxi.

I was truly relieved to see Mother beginning to take an interest in what was to become of us, but I did not dare to tell her that my throat was ominously sore and I feared that I was getting tonsilitis again, a disease which had always plagued me.

On the advice of the taxi-driver, she alighted in an area of tall, narrow, Victorian houses surrounding a series of squares. In the middle of each square was a communal garden which seemed to be permanently locked.

From house to house, up and down the imposing front steps, she dragged herself, knocking on doors which were cautiously opened by black, white, brown and yellow hands. Nobody would consider a family of seven children.

When she had come almost to the point of giving up, she came to a house where the door-bell actually worked. She could hear the old-fashioned clapper bell pealing in the basement. The door was answered by a tiny old lady in a long black-and-white-striped dress and a black apron. Her white hair was brushed up in Edwardian poufs and she looked very clean.

In reply to Mother’s query regarding accommodation, she lifted a finger heavenward and announced piously, ‘The Lord will provide!’

Mother blinked and prepared to turn away.

‘Wait!’ exclaimed the old lady imperiously. ‘I will call Mrs Foster. Please step into the hall.’

Mother stepped in, as requested. The house was not nearly as clean as the old lady, and the lofty hall, with its peeling, olive-green wallpaper, its threadbare, dusty rug and strong smell of cooking, did not inspire confidence. An old-fashioned hatrack and an umbrella-stand made from an elephant’s foot stood near the door, and behind them, set rigidly against the wall, were three Edwardian dining chairs, their woodwork lustreless and their upholstery torn.

The old lady toddled to the back of the hall and shrieked up the stairs in a strong, Liverpool accent, ‘Bissis Fostaire!’

A door upstairs squeaked open and a deeper shriek replied, followed by a heavy tread on the stairs.

‘God bless you, my child,’ said the old lady to Mother, and vanished into what must once have been the dining-room of the house.

There was the sound of steady panting coming closer down the stairs, and Mrs Foster emerged from the gloom of the staircase.

She probably measured nearly as much round as she did in height, a veritable ball of a woman, clad in folds of black chiffon. Her neck was draped in a series of long bead necklaces, such as were worn in the nineteen-twenties, and as she moved they swayed across her bosom making rhythmical tiny clicks as they hit each other. Her pale-blue eyes had a hard, myopic stare and her double chin wobbled, as she continued to pant after reaching the hall.

Mother repeated her inquiry regarding rooms, then sat down suddenly on one of the hall chairs, and fainted.

She was aroused by the strong odour of smelling salts proffered by an old gentleman with a tobacco-stained handlebar moustache. She was vaguely aware that she was leaning against the ample bulk of Mrs Foster who was sitting in the next chair, still panting softly, like a lap-dog.

With the aid of the old gentleman and encouragement from Mrs Foster plodding up behind her, she managed to climb a double flight of stairs into what had been the drawing-room of the house, on the first floor.

The room was furnished as a bed-sitting-room. Two Cairn terriers frolicked under the high double bed; in the window stood a large cage occupied by two dismal grey parrots, and near it a cat lay on the linoleum and watched the birds with narrow, lazy eyes. The unmade bed was piled high with old clothes, and a basket table held a perilous pile of dirty dishes, while the shelf underneath it was filled with dusty ladies’ magazines. A strong aroma of cats and birds permeated everything.

Mother was assisted to a chair by the cheerfully blazing fire and after a moment’s hesitation the old gentleman retired, closing the door quietly after him. Mrs Foster pushed a kettle already standing on the hob round on to the fire.

‘You’ll feel better when you’ve had a cup o’ tea, luv. Would you like to take off yer hat?’

Mother thankfully took off her hat and leaned back in her chair.

‘That was me brother,’ remarked Mrs Foster, gesturing towards the closed door. ‘He has the old breakfast-room and does for himself. Me grandfather built this house.’ She looked round the room proudly. ‘Left it to me father, and he left it to me brother and me. We must be almost the only people left round here as owns their own house.’

She turned round and surveyed Mother, weighing her up quite accurately, as it transpired. She observed the fashionable hat, the dirty dress, the beautifully cut tweed coat, the white hands and, finally, the dead, grey face.

‘Been real ill, haven’t yer, luv?’

‘I have, rather.’

‘And you want a place for you ’n’ the kids?’

‘And my husband.’

‘Oh, I thought mebbe he’d left you.’

‘No.’

Mrs Foster silently considered this information while she assembled a tray of fine, rose-patterned crockery from a corner cupboard and made the tea.

She poured Mother a cup of tea, ladling a generous amount of sugar into it, and then sat down herself, stirring her own tea with slow, thoughtful turning of the battered spoon.

‘I’ve got two rooms and an attic at the top of the house,’ she said. ‘I hadn’t had in mind to have kids in them.’ She paused and ran her tongue round her ill-fitting, artificial teeth. ‘I had three kids there before, but they was little horrors, if you know what I mean. I don’t suppose yours will be that bad.’

‘They are fairly well-mannered,’ Mother assured her hopefully. She sipped her over-sweet tea and its scalding heat began to revive her.

‘I got two married couples and two single ladies in the rooms underneath. The married ones is at work all day, so they won’t hear the noise, and the ladies – well, there’s plenty like them, if they don’t like it.’ She put her spoon into the saucer with a decisive smack, her mind made up. ‘You can have the rooms for twenty-seven shillings a week – in advance, mind you. There’s a gas meter and gaslight in the kitchen-living-room.’

Mother was too thankful at having found a place for us to live in, to realize that the rent was exorbitant for such accommodation.

‘Is it furnished?’ Mother asked.

‘Yes. There’s enough furniture – and you can add a bit of your own, no doubt.’

Mother put down her cup.

‘I wonder if I may see it?’

‘Certainly, if you feel OK now.’

Laboriously, Mother climbed thirty-two more stairs; they were covered in ancient linoleum in which the holes threatened to trip her up from time to time.

There was a kitchen-living-room with a small bedroom fireplace. It contained a wooden table, two straight chairs, a cupboard with odds and ends of crockery and a couple of saucepans in it, a rickety, bamboo bookcase filled with dusty books and a horse-hair sofa exhibiting its intestines.

The bedroom held a black metal double bed, covered with a lumpy, stained mattress, and an ancient wardrobe with a broken door and no mirror. A further small staircase led to an attic which held another double bed. This bed lacked a leg and one corner was held up by a pile of bricks. Two trunks lay in a corner, and an old door was propped against one wall. A forgotten candlestick lay on the floor by the bed. All the floors had some linoleum on them, with dirty, wooden floor showing through in places, and all the windows were shrouded in lace curtains, grey and ragged with age.

Mother looked around her in despair.

‘Nobody’d take seven children nowadays,’ puffed Mrs Foster, as they descended the stairs once more.

Mother knew this to be true and, since the accommodation represented at least a roof under which to shelter, she said, ‘I appreciate that, and I will take the rooms.’

They went back to Mrs Foster’s room, a rent book was carefully made out and Mother paid over a week’s rent. She was informed that she could hang clothes out to dry in the tiny, overgrown back garden, but the children could not play there because, to quote Mrs Foster: ‘Me brother faces out back and he can’t stand noise – he’s a professional pianist. He used to play reelly well in a cinema.’

Mother sighed. She must have been sickened by the squalor of the place. She asked how to reach our present rooms by bus and found that a tram went from a nearby corner.

The trams were open at the front and back and the driver in a shabby uniform augmented by a huge scarf round his neck stood exposed to wind and rain, his foot for ever on his clanging bell. The conductor, not quite so well armoured against the elements, heaved young and old on and off, crammed the vehicle with loud admonitions to ‘Move farther daan t’ back there and make some room for them as comes atter yer’, and collected the fares into his leather pouch with jingling efficiency, as he shoved and pushed his way between his close-packed passengers.

As she sat swaying in the noisy vehicle, Mother watched them work and realized that Mrs Foster had not asked if Father was employed or not; we discovered later that she had taken it for granted that he was not.

Darkness had long since fallen when Mother at last staggered into our living-room and collapsed on to the settee.

Seven

Half an hour after moving into our new abode on the following Monday, we began to appreciate some of the difficulties of living there.

Our coal was to be kept in a cupboard by the back door of the basement, where a series of old pantries had been converted for this purpose. This meant that every bucketful had to be carried up sixty-four stairs. We were to share the bathroom on the first floor with eleven other residents, and this meant innumerable trips for me up and down thirty-two stairs, since Brian, Tony and Avril were far too scared of the dark staircase and crypt-like, filthy bathroom to go down alone, and they needed help to manage in such a dirty place. I was getting resigned to disgusting bathrooms – they seemed to be part of the way of life in Liverpool, as I saw it.

The gas for the light in the living-room, and for a gas stove if we had had one to put in, came through a slot meter which ate pennies at an alarming rate. We did not know that such subsidiary meters were installed and set by landlords at the highest rate they thought they could squeeze out of their tenants. The landlords emptied these meters. They had only to pay the gas company the amount calculated on the reading of the main house meter in the basement, and they pocketed quite a substantial profit on this transaction, in addition to their rent. A more worldly-wise person than my mother would have inserted a penny and run the gas, to see how long a penny lasted, before accepting the tenancy.

Father went out and stopped a passing coal-cart, and the man brought in a sack of coal. He then went to buy cigarettes at a tiny corner store. Both he and Mother had been heavy smokers and found their enforced abstinence hard to bear.

We had brought with us on our tram journey a little oatmeal, a few potatoes, sugar and tea. There was still some baby food for Edward, and, since it was late afternoon by the time we arrived and Edward was whimpering, I made a bottle of formula and then some porridge for the other children. Alan had managed to get a smoky fire going, having lugged a handleless bucket full of coal upstairs by hugging it to his chest. His shirt, already dirty from a week’s wear, was now streaked with coal dust.

Although my head was throbbing and my throat was very sore, I ate some porridge gratefully.

As there was no hot water in the bathroom, I afterwards heated pans of water on our fire, and, starting with Avril, washed all the children, except Alan, who washed himself. Little Tony, fair and silent like Fiona, felt very hot, too, and I sat him on my knee and got him back into his grubby clothes as fast as possible.

I tucked Alan, Brian and Tony up in the bed in the attic, spreading over them their three overcoats, and left them squabbling with each other regarding the fair distribution of room in the bed.

My weary mother had been resting on the bed in the bedroom, and we now held a hasty debate about where Fiona, Avril and I should sleep, it being tacitly agreed that Mother, still in pain, had to have a bed. After a long argument, Father and I brought down into the bedroom the old door which had been left in the attic. We propped this up at each corner with a pile of long-forgotten Victorian books taken from the bamboo bookcase, and then covered it with crumpled newspaper found in the wardrobe. Avril had a wonderful time chasing the spiders we dislodged from the bookcase when we took the books out. She was delighted that Fiona, she and I were going to share this improbable bed. Father and Edward would share Mother’s bed.

Mother got up and went into the living-room, while I put Avril to bed, and when I joined my parents later, they were quietly muttering reproaches at each other through clouds of cigarette smoke. The problem was that we had only three shillings left from our parish relief, and we had to live, somehow, nearly three more days until Thursday afternoon when the benevolent parish would disgorge another forty-three shillings.

As I entered they broke off their recriminations and Father told me to go to bed. I went, thankfully, clinging to Fiona because I felt so dizzy. Fiona, as she took off her shoes preparatory to crawling in beside a soundly sleeping Avril, was crying silently as if her heart was already broken. Avril refused to make room for us when we pushed her gently, and grumbled drowsily that it was her bed. Desperate with the need to lie down, I slapped her legs and, with a howl and an occasional kick at her not-too-loving sisters, she made way.

With nothing over us except our overcoats, and only newspaper under us, it was unbearably cold, and yet at times I felt dreadfully hot.

After a broken night of bad dreams, through which I could hear Edward crying steadily most of the time, I staggered out of bed when Mother called me. I could hardly speak and my throat was swollen from ear to chin.

With eyes still closed she told me in a whisper to call the others, get them ready for school, cut them some bread to eat and make some milkless tea to drink.

Obediently, I built a fire and when I had fanned it with a newspaper into some semblance of heat, I put a pan of water on to it for the tea. Fiona got up from her rustling couch, leaving Avril still slumbering, and without being bidden, went downstairs to wash in the bathroom.

‘The Minister’s soap is nearly finished,’ she reported as she brought the remains of the tablet back to me.

I went upstairs to call the boys and clung to the rickety banister because of the dizziness that enveloped me. The boys were not making their usual rumpus, and I found Alan anxiously surveying a tearful Tony, whose neck was as swollen as mine, while Brian, his small brown face looking wizened and old, was lying miserably on the mattress and saying that he didn’t feel well and he wanted to go home.

‘I’ll tell Mother,’ I said, through nearly closed lips. I noticed, in terror, that we all seemed to have very large red spots on us – mine itched abominably.

Mother looked so utterly defeated when I told her about the boys and when she had really looked at me that my heart went out to her. She woke Father, who had been sleeping the deep sleep of exhaustion.

He sat up quickly, looking very quaint in his rumpled outer clothes, and put on his spectacles.

He peered at me in an effort to persuade his slumber-ridden eyes to focus.

‘I think it’s mumps,’ he said incredulously.

‘It’s my old tonsilitis,’ I said in a whisper. ‘My ear hurts like it always does when tonsilitis is coming.’

My voice and the room seemed to be receding from me and I burned with heat.

‘I think you have mumps as well.’

‘Does mumps bring you out in spots?’ I asked.

He was scratching absent-mindedly at himself, as I spoke.

‘Oh my God!’

He looked at his own arms, and then at my bright red tummy, which I obligingly bared for his inspection.

‘Bug bites, I think,’ he said slowly. ‘Saw them in the army.’

Slow tears welled into Mother’s eyes.

‘I can’t bear it!’ she cried out suddenly. ‘I can’t bear it!’ She hammered the mattress with closed fists. ‘I can’t bear it!’ she screamed, her pretty face distorted. ‘I can’t stand any more.’

She continued to shriek hysterically as we gaped at her in terrified silence. For me the scene was almost totally unreal, as fever gained on me; yet I knew that one of my parents had nearly reached the end of the amount of suffering she could accept, and it was difficult for me to contain my own screams of sheer fright.

There was the sound of heavy feet on the stairs and a coarse male voice shouted up, ‘For Christ’s sake, shut up up there!’

In spite of the pain it gave my throat, I began to cry.

‘Don’t cry, Mummy,’ I begged, ‘we’ll get through somehow.’

Father, ever optimistic like Mr Micawber that something would turn up, bestirred himself and scrambled out of bed.

‘Yes, don’t cry,’ he said kindly. ‘I’ll tell Mrs Foster about the bugs – she’ll probably do something about them.’

Having seen Mrs Foster I doubted this, but I heartily agreed. Anything, I thought, to get that desperate look off Mother’s face and stop her screaming.

Slowly, as Father pottered round trying to bring some order to his distraught family, her cries gave way to sobs and she laid her head down on the mattress. She continued to weep, sobbing quietly to herself for hours.

Father trailed down to the basement to fetch some more coal and coaxed the fire into a more cheerful blaze than I had been able to create. Then we all went and stood by it while he took us one by one and looked us over.

Mother wept on, Edward and Avril slept.

In his opinion, Father said with a sigh, Tony and I had mumps. In addition, I undoubtedly had tonsilitis. Everybody was so used to my sporadic bouts of tonsilitis that this latter pronouncement did not bring me any particular sympathy. Rather, it was taken as an example of my usual awkwardness and waywardness of character. As Father said, ‘You would! Just at this time.’

It was presumed that Brian was also sickening with mumps.

We three sick children were piled into the attic bed. I hardly knew, by this time, what was happening around me. Apparently, Mother was persuaded to feed Edward, when he woke, and Father fed Fiona and Alan. He then took them to their new school, where he had to part with fourpence for a week’s fees.

I am not sure how my parents managed during the next few days, except that, according to Alan, they pawned my overcoat for two shillings in order to be able to buy coal. I remember, between bouts of delirium, seeing my mother crawling about, sometimes literally on her hands and knees, tears streaming down her face, as she struggled to look after Edward; and Fiona bringing me drinks of hot water with a tiny piece of Oxo cube dissolved in it.

The pain in my ears was intolerable, but there was no doctor to paint my throat with glycerine and tannin, no hot-water-bottle or aspirin to ease the searing pain, no drops in my ears to encourage a discharge. The mumps soon decreased, but it was several days before the agony in my ears suddenly diminished. There was a heavy discharge from them on to the bare mattress and my temperature began to go down. I became aware that Brian and Tony were no longer with me, and I called out, my voice seeming muffled and far away to me.

They both came clattering up the attic stairs.

Their faces seemed to have shrunk far more than the vanquished mumps justified. Brian looked more monkeylike than ever, and Tony’s blue eyes and the bones of his head seemed grotesquely prominent. They both had large, scarlet spots about their faces and necks.

‘It’s very quiet,’ I whispered. ‘Where is everyone?’

‘Alan and Fiona are at school. Mummy’s in the living-room with the baby. We have to be quiet so she can rest.’

‘That is right,’ I said, trying to sit up and finding that the room swam around me, so that I was glad to lie down again. I looked imploringly at Brian. ‘I’m so cold, Brian. Could you find something more to cover me with?’

He immediately went and fetched his overcoat and put it over my shoulders.

‘Where is Daddy?’

‘He’s gone to see Mr Parish,’ volunteered Tony.

I smiled at his name for the public assistance committee.

‘Be a darling and bring me my specs,’ I commanded him. ‘I think I have to stay here a little longer. I still feel a bit hot between the shivers. Gosh, I do smell!’

The sides of my head were sticky with the discharge from my ears, but for the moment I had neither the strength nor the will to do anything about it.

‘Tell Daddy I’m better, when he comes,’ I said. ‘You can play in here if you like.’ And I closed my eyes, thankful to be free of pain at last, and fell into a deep sleep while the boys played tag up and down the room. I awoke much later to find Father bending over me, trying to see me by the light of a candlestub. He felt my head. It was cool.

‘Feel better?’ he asked.

‘Yes.’

‘That’s my girl.’

‘How is Mummy?’

‘Much better. She is walking quite well now.’

‘Has she stopped crying?’ I could not keep a hint of fear out of my voice.

Father looked old and very tired, as he said quietly, ‘Yes, she is better now.’

‘Can I get up?’

‘Yes, I think it would be a good idea. We’ve got a fire today, so it’s warmer in the other room.’

I craved a hot cup of tea and I hoped that if we had a fire to boil the water we might also have a little tea in the cupboard. My legs almost refused to obey me and I clung to Father’s arm as I shuffled across the floor, down the attic stairs and into the living-room, where I was greeted rapturously by Fiona and Alan and with a wan smile by my exhausted mother. Avril was sitting on the floor in a corner, her face red and tear-stained, getting over a tantrum.