Полная версия

Twopence to Cross the Mersey

Under Mother’s instructions, I made a feed for Edward and then fed him: he was ravenous and took the whole small bottleful. Father cooked sausages on the smoking fire, found a knife in the kitchen and cut the bread and spread it with margarine. We sat around on whatever we could find and ate a sausage apiece in our fingers. He managed to boil a pan of water and make tea in it. Mother drank much and ate little, refusing a sausage which was happily snatched up by Avril. Father finally ate, and only afterwards I realized that he had not had a sausage, and I felt a crushing sense of guilt about it.

Our landlady called down the stairs to say that she could hear the coalman coming, and my father looked aghast. The coal donated by our landlady was already nearly consumed and we had exactly a penny left. We could do nothing, and sat hopelessly silent, as the shout of ‘Coal, coal, one and nine a hundredweight’ faded down the street.

That was the first of many years of nights I spent tossing restlessly, napping, waking, unable to settle because of cold or gnawing hunger. Four of us, still dressed in our underwear, were packed somehow into one bed, and Father, Alan and Brian were to manage in the other bed. Mother stayed on the settee with the baby. For a long time I lay and listened to my parents quarrelling with each other, while the baby whimpered and Fiona, her head against my shoulder, chattered inconsequently in her own uneasy sleep, her doll clasped tightly to her. I fell into a doze, from which I was awakened by Mother calling me in the early morning. I was glad to leave the bed, which smelled of urine, put on my gym-slip and blouse and go to her.

It had been decided, she said, that Father should enrol Alan, Fiona, Brian and Tony at an elementary school he had noticed on his way to the corner shop the previous night. I was to stay at home and help with the baby. My loud protest that I would get behind with my schooling was sharply hushed. I was to see the children washed and tidied for school and was to divide the remaining bread and margarine between them for breakfast. All this I did, whilst shivering with cold. Brian and Tony were also shivering and were scared of going to school; Fiona and Alan were frankly relieved at the thought of something normal creeping back into their lives.

A breakfastless Father was gone with them for an hour and came back to report the children safely ensconced. He had put into his pocket, when leaving home, an old-fashioned cut-throat razor, and he now did his best to shave with it, in cold water, without soap. The result was not very good, and his clothing, still wet from yesterday’s soaking, looked crumpled and old. He then departed for the employment exchange, a three-mile walk.

Mother, Avril and I sat almost silent in the icy room. Occasionally, we would feed the baby a little of the remaining milk. We warmed it slightly by putting the bottle next to Mother’s skin down the front of her dress, and we wrapped the baby in Mother’s coat, which had not got much wetted the previous day. I then tucked our two precious blankets round both mother and child. I longed to get out of the fetid room, even if it was only to stand at the front door, but I was too afraid of my mother in her present state to ask permission to do so.

The other children came home for lunch, but there was no lunch, and they departed again for school, cold, hungry and in tears, even brave Alan’s lips quivering. Mother, Avril and I, like Father, had neither eaten nor drunk.

The afternoon dragged on and the children returned, except for Fiona.

‘Fiona’s ill,’ explained Alan anxiously. ‘A teacher is going to bring her home in a little while, when she feels better.’

I suppose my mother was past caring, for she said nothing, but, to the griping hunger pains in my stomach, was added a tightening pain of apprehension for Fiona, the frailest of us all. I tried, however, to be cheerful while I helped the boys off with their coats and then put them on again immediately, because they said they were so cold.

The front door bell clanged sonorously through the house. I expected to hear the clatter of our landlady coming down the stairs to open it, but there was no sound from the upper regions of the house, so very diffidently I rose and answered it.

At the door, stood an enormously tall man in long, black skirts. In his arms he carried Fiona.

Four

I quailed before the apparition on the doorstep – it reminded me of an outsize bat and my overstimulated imagination suggested that it might be a vampire; in the chaotic mess that our world had become, anything was possible. The voice that issued from the apparition’s bearded face was, however, gentle and melodious, and asked to see my mother.

Nervously, I invited him (it was obviously male, despite the long, black dress) into the hall, and he slid a whey-faced Fiona to the floor, while I went to see Mother. She told me to bring the gentleman into our room, and, for the first time since our arrival, a slight animation was apparent in her face.

He entered, leading Fiona by the hand, and immediately my mother assumed the gracious manner which had, in the past, contributed to her reputation as an accomplished hostess.

‘Father!’ Her voice was bell-like. ‘This is a pleasure! Come in. Do sit down.’ She ignored poor Fiona, who came and stood by me, and stared dumbly at our new-found friend.

‘Father’? It was beyond me. I had never seen an Anglican priest in high church robes, nor yet a Roman Catholic one, in the small towns in which we had previously lived. I stood, with fingers pressed against my mouth, and wondered what further troubles this visit portended.

He was explaining to Mother that the school was an Anglican Church school. After Fiona had come out of her faint, the headmistress had wormed out of her something of what was happening to us, and had then telephoned him. The advent of four well-dressed, well-behaved children entering a slum school had already caused some stir among the teachers and considerable jeering and cat-calling among the other pupils, so the headmistress had asked him to call upon us. Here he was, he announced gravely, and could he be of help?

As I examined the beautiful, serene face of the young priest, Mother poured out a condensed version of the story of Father’s losses. He was a Liverpool man originally, she said, and had come back to his native city in the hope of earning his living there. To me, the well-edited tale still presented a picture of foolishness, extravagance and carelessness.

Now, at last, I knew why we were in Liverpool and what the word ‘bankruptcy’ really meant to our family. I knew, with terrible clarity, that I would never see my bosom friend, Joan, again, never play with my doll’s house, never be the captain of the hockey team or be in the Easter pageant. My little world was swept away.

I looked at Alan, who was standing equally silently by the window. His eyes met mine and we shared the same sense of desolation. Then his golden eyelashes covered his eyes and shone with tears, half-hidden.

‘Have you no relations who would help you?’ asked the priest.

‘I have no relations,’ said Mother coldly, ‘and my husband’s refused to know us at present.’

The priest combed his beard with his fingers, and smiled when Avril tried to reach up to touch it. He took her hand gently and held it, and within thirty seconds she had established herself triumphantly on his knee, from which safe throne she surveyed the rest of the family gleefully.

‘There is a great deal of unemployment in Liverpool,’ he said. ‘I fear your husband may find difficulty in finding work.’

Mother just stared disconsolately at him.

At that moment Father entered, dragging his feet slowly and looking almost as hopeless as Mother. The children ignored him, the exhausted baby slept.

Desperate to fill the silence, I cried gladly, ‘Daddy!’

He managed to smile faintly.

Mother introduced him formally to the priest, and he sat down and waited politely to hear why the priest was there. This was explained to him, while he shivered with cold and rubbed his blue hands together to restore the circulation.

Finally, the priest said to him, ‘First things first. You must have a fire or your youngest child will die. Probably I can persuade old Wright to bring up a hundredweight of coal. I have some small funds and I will bring some food. After you have eaten perhaps I can advise you a little.’

He put his hand out over the children’s heads in a gesture of blessing, said goodbye, strode out of the room and let himself out of the house.

The boys immediately broke into jubilant conversation with each other at the idea of food, and gradually Father began to relax a little for the same reason, though his face looked pinched and white. He had spent hour upon hour in the employment exchange, being chivvied from one huge queue to another, until he had finally got himself registered for work as a clerk. He was not eligible for unemployment insurance as he had never contributed to that fund, and the employment exchange clerk just laughed when he asked when he might hope to be sent to apply for a job. There were, he said, a hundred men for every job, and my father’s age was a grave difficulty – at thirty-eight he was too old to hope seriously for employment.

He had hardly finished telling us of his adventures, when the doorbell rang again. I answered it quickly this time.

A surly voice from beneath a large hump inquired where it should put t’ coal, and not to keep ’im waiting cos ’e ’adn’t all night to run after folks as ’adn’t enough sense to get it in the daytime.

The landlady had shown me where our coal could be stored, and the coalman clomped through the house behind me, scattering slack liberally around him, and heaved the coal expertly over his head, out of the sack and into a broken-down box in an out-house. Then, still muttering about improvident folks, he stomped back through the passage and departed into the darkness.

I flew in to Mother, and it seemed no time at all before we had a huge fire glowing, with Father’s coat and jacket and Edward’s nappy steaming in front of it. The already heavy atmosphere of the room was intensified by the cloying stench of these garments drying, but we did not care. We learned then that, when one has to choose between warmth and being half-fed, except in the last extremities of starvation, warmth is the better choice.

An hour later the priest presented himself again, carrying two large boxes and accompanied by a boy carrying two more. The boy dropped his burdens on the step and trotted away. The priest came in, at my shy invitation. He smiled at the sight of the comforted children kneeling by the fire between the drying clothes, and, with Father’s aid, he unpacked the boxes.

The table was soon loaded with six loaves of bread, oatmeal, potatoes, sugar, margarine, a tin of baby milk, two bottles of milk, salt, bacon, some tea, a bar of common soap, a pile of torn-up old sheeting (for cleaning, and for the baby, he explained apologetically) and, wonder of wonders, a towel, a big one.

The priest sat down, and called the boys to him, while Father and I made baby formula and porridge, and Alan collected all the dishes he could find. It felt oddly like a Christmas celebration, and even Mother seemed to come a little out of her apathy as she sipped the tea and ate the porridge Father eventually brought to her. I fed the baby while the children stuffed themselves with porridge, bread and margarine and chattered excitedly, Avril’s shrill falsetto and Brian’s contralto occasionally emerging from the general hubbub. At the priest’s insistence, Father and I finally ate, and Father became more his old, lively self.

We boiled another panful of water, and I took Fiona, Brian, Tony and Avril to the bathroom, and washed their hands, faces and knees. They had not had their underclothes off for thirty-six hours and did not smell very sweet, even after my washing efforts, but a quart of water does not go very far in washing four people, and I reasoned that the beds stank so much that they were bound to smell by morning no matter what I did.

Afterwards I took them into the bedroom, tucked their overcoats over them, covered these with a greasy blanket, heard their prayers, and returned to Alan and my parents.

Five

Unemployment was so rampant in Liverpool that the young priest felt it necessary to warn Father that getting work would be a very slow process – he was too kind to say that it would be virtually impossible. He suggested that Father should apply for parish relief.

‘What is that?’ asked Father.

‘Well, it is really the old poor-law relief for the destitute, but it is now administered by the city through the public assistance committee. More help is given by way of allowances rather than by committal to the workhouse.’

Father went white at the mention of the workhouse. I stared in shocked horror at the priest. I had read all of Charles Dickens’s books – I knew about workhouses.

‘I see,’ said Father, his voice not much more than a whisper. ‘I suppose I have no alternative.’

The priest asked about our accommodation, and sat, drumming his finger-tips upon his skirt-clad knee, when he was told that our landlady wanted her rooms back for another tenant, at the end of the week.

At last he spoke.

‘There are a lot of older houses in the south end of the city. You might find a couple of rooms in one of those. Some of them are still quite respectable. There is also a High Church school in that area, which is a little better than an ordinary board school. However, you might have to pay twopence a week for each child at the school – and that might pose a problem.’

Father said optimistically that he could not imagine such a small amount being a problem, once we got settled.

The priest smiled at him pityingly, opened his mouth to speak and then decided otherwise. We would soon learn.

‘Would you like to ask me about anything else?’ he inquired.

‘No, thank you,’ said Mother suddenly. ‘You have been most kind.’

I was surprised at her firmness, and then remembered that neither she nor Father had ever had any great respect for the Church. In addition, the priest represented to her the class of people who, she must have felt, had left her in the lurch when she most needed friends. She had accepted this stranger’s help because she had to, but her grey eyes were steely, when she politely held out her hand to indicate dismissal.

I could see Father beginning to dither, like Bertie Wooster. He was obviously loath to let the priest go and yet was afraid that, if he said anything, Mother might start another bitter family row.

The priest settled the question by getting up abruptly. There was a hurt expression in the mild eyes. He ignored Mother’s hand but inclined his head slightly towards her, as he moved through the crowded room to the door. Alan, Father and I hastened to see him out, with many protestations of gratitude. He bowed gravely, blessed us and, with slow, dignified tread, went down the steps into the darkness.

I closed the door, and stood leaning against the inside of it, while the others went back to the family. I had hoped so much that the young priest would have noticed that there were five children of school age in the family and realized that only four had been enrolled in his school. I had envisaged him instructing Father to send me with the others for lessons the following morning. But he had not noticed. I fought back my disappointment and told myself that I would probably go to school as soon as we were settled in a more permanent home, and then I would be able to play in the fresh air with new friends and perhaps even be top of the class in English once more.

The untold amount of anguish that I could have been saved if the good priest had only counted his little flock is hard to imagine. Undoubtedly, the education committee and its army of attendance officers and inspectors would have enforced my right to schooling had he but observed and reported this discrepancy.

I slunk back into the room.

‘A capable man,’ Mother was saying to Father, with a look which added ‘unlike you’.

Before this subtle barb could be plucked out and shot back, she announced that she would go up to the bathroom. She had, hitherto, managed to use an ancient, cracked chamber-pot found under one of the beds.

Refusing Father’s help with a lofty air, but using me and anything else she could to hold on to, she slowly eased her way into the hall and halfway up the narrow staircase. We sat down and rested on the stairs, and then continued. This was her first real effort to walk since her return from hospital, and she came down the stairs by going from step to step on her bottom. In spite of all the calamities she was undergoing, her strong body was healing and all that was required to return her to reasonable physical health was the will to try and strengthen her muscles. Her pretty, pink wool dress was already spoiled where the baby had wetted it, and the journey down the dusty stairs did not improve it.

The following day, she pottered round the room quite a lot, while Father went in search of that mysterious personage, ‘The Parish’. The children, including Fiona, went to school and I again stayed at home. Father had made the fire and I managed to heat some water and wash Edward. When the sun came out about mid-morning, on Mother’s instructions I gingerly wrapped the baby in one of the blankets.

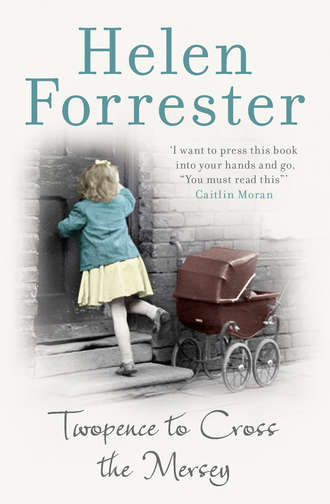

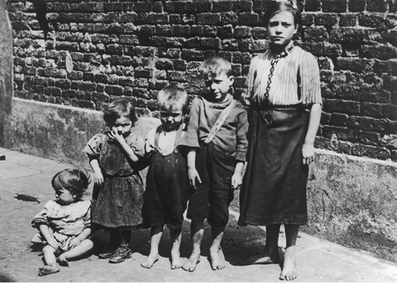

Line of street children

‘Take him outside and walk up and down in the sun with him,’ she said.

I was gone in a flash, the startled child whimpering at my sudden movements.

The bliss of being out of the fetid room overwhelmed me, though the street was not much better. The wind, sweeping in from the estuary, was, however, invigorating despite the gas fumes carried on it. A blank brick wall shielded one side of the street, and from behind it came the shuddering sounds of shunting trains.

The house in which we were staying was one of a row of shabby, jerry-built Edwardian houses, with a grocery store at one end of the block and a public house at the other end. Toddlers with runny noses and sores on their faces scrabbled around in the gutter. An older boy, a piece of jammy bread in one hand, flitted barefoot up the road and called something insolent after me. At the door of the public house, droopy men in shabby raincoats waited for opening time. They stared at me, and I wondered why, but I must have been an unusual sight in my private school uniform, ugly velour hat rammed neatly down on to my forehead, and carrying an almost new baby up and down the pavement. School uniforms would not, in those days, have been seen in such a slummy area. I endured the silent observation with embarrassment.

A sudden diversion brought a number of women to their doors, and in some houses ragged blinds and curtains were hastily drawn.

A funeral procession came slowly down the street, led by a gaunt man in deep black. He was followed by the hearse, a wonderful creation of black and silver, with glass side panels and small, black curtains drawn back to expose the fine wooden coffin. The coffin itself was almost covered by wreath after wreath of gorgeous flowers, including many arum lilies. The four horses which drew the hearse were well matched black carriage-horses and as they paced slowly along they tossed their heads as if to show off the long black plumes fastened to their bridles. They were driven by a coachman draped in a black cloak and wearing a top hat which shone in the sun; his face beneath the shadow of the hat looked suitably lugubrious.

The men outside the public house, with one accord, removed their caps, and the toddlers scampered out of the gutter and took refuge behind me.

The hearse was followed by a carriage in which sat a woman dressed in heavy widow’s weeds. She sat well forward, so that all could see her and dabbed her purple face from time to time with a white handkerchief edged with black. Occasionally, she would bow, in a fair imitation of royalty, to one of the onlookers and then put her handkerchief again to her dry eyes. Opposite her, sat two pale, acne-pocked young men in black suits too large for them, looking thoroughly uncomfortable.

The widow’s carriage was followed by five other carriages, each filled with black-clad mourners.

‘Smith always does ’is funerals very nice,’ said a voice behind me, rich with approval.

I glanced back quickly.

Two fat women, garbed in grubby, flowered cotton frocks, their arms tucked into their equally grubby pinafores to keep them a little warm, had come out to see the procession.

‘’E does. Better’n old Johnson. ’E did her daughter’s wedding, too.’

There was a faint chuckle from the first woman. ‘She’s got more money to spend on ’er ’usband’s funeral than she ’ad on the wedding, what with ’is insurance and all.’ There was silence for a moment, then the voice continued, ‘Ah wonder if ’er Joe will keep on the rag-and-bone business?’

Her companion murmured some reply, but I was too intrigued at the idea of a rag-and-bone man having such a large funeral procession to be interested in them further. Everybody I had seen that morning had looked so poor, and yet one of their number was being laid to rest like a prince. Surely the money such a thing would cost was needed for food.

The sun went in and my spirits drooped as the cortège turned round the corner grocery store and disappeared. Like most children, I was afraid of death and the funeral seemed an ill omen to me.

I turned, and went indoors.

Alan came home at lunch-time with a black eye. A boy had asked him if he carried a marble in his mouth, because he spoke so queerly. Alan had replied that he spoke properly, not like a half-baked savage. The half-baked savage had then blacked his eye for him.

‘He’s got a black eye, too,’ said Alan with some satisfaction as I put a wet piece of cloth over the injured part. ‘You’re lucky not to have to go to this school – even the girls fight.’

‘I’d like to go, just to get out of this horrid house,’ I said vehemently. ‘And, oh, Alan, I’m so afraid Father won’t bother about sending me. You know he has always said that all a woman needed was to be able to read and write, and I can do that.’

‘He’ll have to send you. Isn’t there a law about it?’

‘Yes there is.’

‘Well, the school inspector will tell him he must.’

I removed the wet cloth from his eye and cooled it again under the tap. ‘If he knew I existed, I expect he would,’ I agreed. ‘But, Alan, I was thinking about it all night and if Father never tells them about me they will never know I am here.’

He looked at me uneasily before closing his eyes again so that I could replace the cloth over the blackened one. After wincing at my ministrations, he said doubtfully, ‘Probably when we get a proper house, he’ll arrange for you to go.’

‘I hope so,’ I responded earnestly; but I remembered the funeral and my stomach muscles were clenched with apprehension.

Six

Father returned at lunch-time with food vouchers to last us for two days, while ‘The Parish’ made inquiries as to the rates of relief paid in the small town from which we came. Apparently, this town would have to reimburse the Liverpool public assistance committee for any relief given to us. It was expected that we would be granted forty-three shillings per week. This sum must cover everything for nine people – rent, food, clothing, heating, lighting, washing, doctor, medicines, haircuts and the thousand and one needs of a growing family.

Mother looked at him disbelievingly.

‘It’s impossible,’ she said, her unpainted face puckered up with surprise. She was used to spending more than that on a hat.