Полная версия

The Irrational Bundle

Now you are on your second task: you’re shopping for your suit. You find a luxurious gray pinstripe suit for $455 and decide to buy it, but then another customer whispers in your ear that the exact same suit is on sale for only $448 at another store, just 15 minutes away. Do you make this second 15-minute trip? In this case, most people say that they would not.

But what is going on here? Is 15 minutes of your time worth $7, or isn’t it? In reality, of course, $7 is $7—no matter how you count it. The only question you should ask yourself in these cases is whether the trip across town, and the 15 extra minutes it would take, is worth the extra $7 you would save. Whether the amount from which this $7 will be saved is $10 or $10,000 should be irrelevant.

This is the problem of relativity—we look at our decisions in a relative way and compare them locally to the available alternative. We compare the relative advantage of the cheap pen with the expensive one, and this contrast makes it obvious to us that we should spend the extra time to save the $7. At the same time, the relative advantage of the cheaper suit is very small, so we spend the extra $7.

This is also why it is so easy for a person to add $200 to a $5,000 catering bill for a soup entrée, when the same person will clip coupons to save 25 cents on a one-dollar can of condensed soup. Similarly, we find it easy to spend $3,000 to upgrade to leather seats when we buy a new $25,000 car, but difficult to spend the same amount on a new leather sofa (even though we know we will spend more time at home on the sofa than in the car). Yet if we just thought about this in a broader perspective, we could better assess what we could do with the $3,000 that we are considering spending on upgrading the car seats. Would we perhaps be better off spending it on books, clothes, or a vacation? Thinking broadly like this is not easy, because making relative judgments is the natural way we think. Can you get a handle on it? I know someone who can.

He is James Hong, cofounder of the Hotornot.com rating and dating site. (James, his business partner Jim Young, Leonard Lee, George Loewenstein, and I recently worked on a research project examining how one’s own “attractiveness” affects one’s view of the “attractiveness” of others.)

For sure, James has made a lot of money, and he sees even more money all around him. One of his good friends, in fact, is a founder of PayPal and is worth tens of millions. But Hong knows how to make the circles of comparison in his life smaller, not larger. In his case, he started by selling his Porsche Boxster and buying a Toyota Prius in its place.4

“I don’t want to live the life of a Boxster,” he told the New York Times, “because when you get a Boxster you wish you had a 911, and you know what people who have 911s wish they had? They wish they had a Ferrari.”

That’s a lesson we can all learn: the more we have, the more we want. And the only cure is to break the cycle of relativity.

Reflections on Dating and Relativity

In Chapter 1, on relativity, I offered some dating advice. I proposed that if you want to go bar-hopping, you should consider taking along someone who looks similar to you but who is slightly less attractive than you are. Because of the relative nature of evaluations, others would perceive you not only as cuter than your decoy, but also as better-looking than other people in the bar. By the same logic, I also pointed out that the flip side of this coin is that if someone invites you to be his or her wingman (or wingwoman), you can easily figure out what your friend really thinks of you. As it turns out, I forgot to include one important warning that came courtesy of the daughter of a colleague of mine from MIT.

“Susan” was an undergraduate at Cornell who wrote to me, saying she was delighted with my trick and that it had worked wonderfully for her. Once she found the ideal decoy, her social life improved. But a few weeks later she wrote again, telling me that she’d been at a party where she’d had a few drinks. For some odd reason, she decided to tell her friend why she invited her to accompany her everywhere. The friend was understandably upset, and the story did not end well.

The moral of this story? Never, ever tell your friend why you’re asking him or her to come with you. Your friend might have suspicions, but for the love of God, don’t eliminate all doubt.

Reflections on Traveling and Relativity

When Predictably Irrational came out, I went on a book tour that lasted six straight weeks. I traveled from airport to airport, city to city, radio station to radio station, talking to reporters and readers for what seemed like days on end, without engaging in any type of personal discussion. Every conversation was short, “all business,” and focused on my research. There was no time to enjoy a cup of coffee or a beer with any of the wonderful people I encountered.

Toward the end of the tour I found myself in Barcelona. There I met Jon, an American tourist who, like me, did not speak any Spanish. We felt an immediate camaraderie. I imagine this kind of bonding happens often with travelers from the same country who are far from home and find themselves sharing observations about how they differ from the locals around them. Jon and I ended up having a wonderful dinner and a deeply personal discussion. He told me things that he seemed not to have shared before, and I did the same. There was an unusual closeness between us, as if we were long-lost brothers. After staying up very late talking, we both needed to sleep. We would not have a chance to meet again before parting ways the following morning, so we exchanged e-mail addresses. This was a mistake.

About six months later, Jon and I met again for lunch in New York. This time, it was hard for me to figure out why I’d felt such a connection with him, and no doubt he felt the same. We had a perfectly amicable and interesting lunch, but it lacked the intensity of our first meeting, and I was left wondering why.

In retrospect, I think it was because I’d fallen victim to the effects of relativity. When Jon and I first met, everyone around us was Spanish, and as cultural outsiders we were each other’s best alternative for companionship. But once we returned home to our beloved American families and friends, the basis for comparison switched back to “normal” mode. Given this situation, it was hard to understand why Jon or I would want to spend another evening in each other’s company rather than with those we love.

My advice? Understand that relativity is everywhere, and that we view everything through its lens—rose-colored or otherwise. When you meet someone in a different country or city and it seems that you have a magical connection, realize that the enchantment might be limited to the surrounding circumstances. This realization might prevent you from subsequent disenchantment.

CHAPTER 2

The Fallacy of Supply and Demand

Why the Price of Pearls—and Everything Else—

Is Up in the Air

At the onset of World War II, an Italian diamond dealer, James Assael, fled Europe for Cuba. There, he found a new livelihood: the American army needed waterproof watches, and Assael, through his contacts in Switzerland, was able to fill the demand.

When the war ended, Assael’s deal with the U.S. government dried up, and he was left with thousands of Swiss watches. The Japanese needed watches, of course. But they didn’t have any money. They did have pearls, though—many thousands of them. Before long, Assael had taught his son how to barter Swiss watches for Japanese pearls. The business blossomed, and shortly thereafter, the son, Salvador Assael, became known as the “pearl king.”

The pearl king had moored his yacht at Saint-Tropez one day in 1973, when a dashing young Frenchman, Jean-Claude Brouillet, came aboard from an adjacent yacht. Brouillet had just sold his air-freight business and with the proceeds had purchased an atoll in French Polynesia—a blue-lagooned paradise for himself and his young Tahitian wife. Brouillet explained that its turquoise waters abounded with black-lipped oysters, Pinctada margaritifera. And from the black lips of those oysters came something of note: black pearls.

At the time there was no market for Tahitian black pearls, and little demand. But Brouillet persuaded Assael to go into business with him. Together they would harvest black pearls and sell them to the world. At first, Assael’s marketing efforts failed. The pearls were gunmetal gray, about the size of musket balls, and he returned to Polynesia without having made a single sale. Assael could have dropped the black pearls altogether or sold them at a low price to a discount store. He could have tried to push them to consumers by bundling them together with a few white pearls. But instead Assael waited a year, until the operation had produced some better specimens, and then brought them to an old friend, Harry Winston, the legendary gemstone dealer. Winston agreed to put them in the window of his store on Fifth Avenue, with an outrageously high price tag attached. Assael, meanwhile, commissioned a full-page advertisement that ran in the glossiest of magazines. There, a string of Tahitian black pearls glowed, set among a spray of diamonds, rubies, and emeralds.

The pearls, which had shortly before been the private business of a cluster of black-lipped oysters, hanging on a rope in the Polynesian sea, were soon parading through Manhattan on the arched necks of the city’s most prosperous divas. Assael had taken something of dubious worth and made it fabulously fine. Or, as Mark Twain once noted about Tom Sawyer, “Tom had discovered a great law of human action, namely, that in order to make a man covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.”

HOW DID THE pearl king do it? How did he persuade the cream of society to become passionate about Tahitian black pearls—and pay him royally for them? In order to answer this question, I need to explain something about baby geese.

A few decades ago, the naturalist Konrad Lorenz discovered that goslings, upon breaking out of their eggs, become attached to the first moving object they encounter (which is generally their mother). Lorenz knew this because in one experiment he became the first thing they saw, and they followed him loyally from then on through adolescence. With that, Lorenz demonstrated not only that goslings make initial decisions based on what’s available in their environment, but that they stick with a decision once it has been made. Lorenz called this natural phenomenon imprinting.

Is the human brain, then, wired like that of a gosling? Do our first impressions and decisions become imprinted? And if so, how does this imprinting play out in our lives? When we encounter a new product, for instance, do we accept the first price that comes before our eyes? And more importantly, does that price (which in academic lingo we call an anchor) have a long-term effect on our willingness to pay for the product from then on?

It seems that what’s good for the goose is good for humans as well. And this includes anchoring. From the beginning, for instance, Assael “anchored” his pearls to the finest gems in the world—and the prices followed forever after. Similarly, once we buy a new product at a particular price, we become anchored to that price. But how exactly does this work? Why do we accept anchors?

Consider this: if I asked you for the last two digits of your social security number (mine are 79), then asked you whether you would pay this number in dollars (for me this would be $79) for a particular bottle of Côtes du Rhône 1998, would the mere suggestion of that number influence how much you would be willing to spend on wine? Sounds preposterous, doesn’t it? Well, wait until you see what happened to a group of MBA students at MIT a few years ago.

“NOW HERE WE have a nice Côtes du Rhône Jaboulet Parallel,” said Drazen Prelec, a professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, as he lifted a bottle admiringly. “It’s a 1998.”

At the time, sitting before him were the 55 students from his marketing research class. On this day, Drazen, George Loewenstein (a professor at Carnegie Mellon University), and I would have an unusual request for this group of future marketing pros. We would ask them to jot down the last two digits of their social security numbers and tell us whether they would pay this amount for a number of products, including the bottle of wine. Then, we would ask them to actually bid on these items in an auction.

What were we trying to prove? The existence of what we called arbitrary coherence. The basic idea of arbitrary coherence is this: although initial prices (such as the price of Assael’s pearls) are “arbitrary,” once those prices are established in our minds they will shape not only present prices but also future prices (this makes them “coherent”). So, would thinking about one’s social security number be enough to create an anchor? And would that initial anchor have a long-term influence? That’s what we wanted to see.

“For those of you who don’t know much about wines,” Drazen continued, “this bottle received eighty-six points from Wine Spectator. It has the flavor of red berry, mocha, and black chocolate; it’s a medium-bodied, medium-intensity, nicely balanced red, and it makes for delightful drinking.”

Drazen held up another bottle. This was a Hermitage Jaboulet La Chapelle, 1996, with a 92-point rating from the Wine Advocate magazine. “The finest La Chapelle since 1990,” Drazen intoned, while the students looked up curiously. “Only 8,100 cases made . . .”

In turn, Drazen held up four other items: a cordless trackball (TrackMan Marble FX by Logitech); a cordless keyboard and mouse (iTouch by Logitech); a design book (The Perfect Package: How to Add Value through Graphic Design); and a one-pound box of Belgian chocolates by Neuhaus.

Drazen passed out forms that listed all the items. “Now I want you to write the last two digits of your social security number at the top of the page,” he instructed. “And then write them again next to each of the items in the form of a price. In other words, if the last two digits are twenty-three, write twenty-three dollars.”

“Now when you’re finished with that,” he added, “I want you to indicate on your sheets—with a simple yes or no—whether you would pay that amount for each of the products.”

When the students had finished answering yes or no to each item, Drazen asked them to write down the maximum amount they were willing to pay for each of the products (their bids). Once they had written down their bids, the students passed the sheets up to me and I entered their responses into my laptop and announced the winners. One by one the student who had made the highest bid for each of the products would step up to the front of the class, pay for the product,* and take it with them.

The students enjoyed this class exercise, but when I asked them if they felt that writing down the last two digits of their social security numbers had influenced their final bids, they quickly dismissed my suggestion. No way!

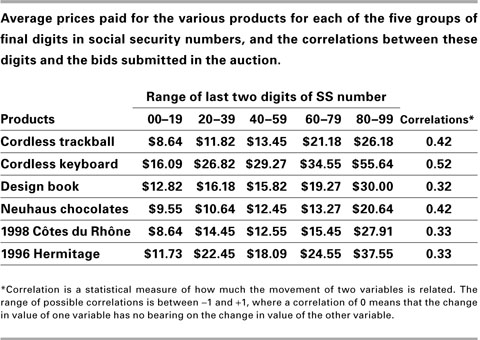

When I got back to my office, I analyzed the data. Did the digits from the social security numbers serve as anchors? Remarkably, they did: the students with the highest-ending social security digits (from 80 to 99) bid highest, while those with the lowest-ending numbers (1 to 20) bid lowest. The top 20 percent, for instance, bid an average of $56 for the cordless keyboard; the bottom 20 percent bid an average of $16. In the end, we could see that students with social security numbers ending in the upper 20 percent placed bids that were 216 to 346 percent higher than those of the students with social security numbers ending in the lowest 20 percent (see table on the facing page).

Now if the last two digits of your social security number are a high number I know what you must be thinking: “I’ve been paying too much for everything my entire life!” This is not the case, however. Social security numbers were the anchor in this experiment only because we requested them. We could have just as well asked for the current temperature or the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP). Any question, in fact, would have created the anchor. Does that seem rational? Of course not. But that’s the way we are—goslings, after all.*

The data had one more interesting aspect. Although the willingness to pay for these items was arbitrary, there was also a logical, coherent aspect to it. When we looked at the bids for the two pairs of related items (the two wines and the two computer components), their relative prices seemed incredibly logical. Everyone was willing to pay more for the keyboard than for the trackball—and also pay more for the 1996 Hermitage than for the 1998 Côtes du Rhône. The significance of this is that once the participants were willing to pay a certain price for one product, their willingness to pay for other items in the same product category was judged relative to that first price (the anchor).

This, then, is what we call arbitrary coherence. Initial prices are largely “arbitrary” and can be influenced by responses to random questions; but once those prices are established in our minds, they shape not only what we are willing to pay for an item, but also how much we are willing to pay for related products (this makes them coherent).

Now I need to add one important clarification to the story I’ve just told. In life we are bombarded by prices. We see the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) for cars, lawn mowers, and coffeemakers. We get the real estate agent’s spiel on local housing prices. But price tags by themselves are not necessarily anchors. They become anchors when we contemplate buying a product or service at that particular price. That’s when the imprint is set. From then on, we are willing to accept a range of prices—but as with the pull of a bungee cord, we always refer back to the original anchor. Thus the first anchor influences not only the immediate buying decision but many others that follow.

We might see a 57-inch LCD high-definition television on sale for $3,000, for instance. The price tag is not the anchor. But if we decide to buy it (or seriously contemplate buying it) at that price, then the decision becomes our anchor henceforth in terms of LCD television sets. That’s our peg in the ground, and from then on—whether we shop for another set or merely have a conversation at a backyard cookout—all other high-definition televisions are judged relative to that price.

Anchoring influences all kinds of purchases. Uri Simonsohn (a professor at the University of Pennsylvania) and George Loewenstein, for example, found that people who move to a new city generally remain anchored to the prices they paid for housing in their former city. In their study they found that people who move from inexpensive markets (say, Lubbock, Texas) to moderately priced cities (say, Pittsburgh) don’t increase their spending to fit the new market.* Rather, these people spend an amount similar to what they were used to in the previous market, even if this means having to squeeze themselves and their families into smaller or less comfortable homes. Likewise, transplants from more expensive cities sink the same dollars into their new housing situation as they did in the past. People who move from Los Angeles to Pittsburgh, in other words, don’t generally downsize their spending much once they hit Pennsylvania: they spend an amount similar to what they used to spend in Los Angeles.

It seems that we get used to the particularities of our housing markets and don’t readily change. The only way out of this box, in fact, is to rent a home in the new location for a year or so. That way, we adjust to the new environment—and, after a while, we are able to make a purchase that aligns with the local market.

SO WE ANCHOR ourselves to initial prices. But do we hop from one anchor price to another (flip-flopping, if you will), continually changing our willingness to pay? Or does the first anchor we encounter become our anchor for a long time and for many decisions? To answer this question, we decided to conduct another experiment—one in which we attempted to lure our participants from old anchors to new ones.

For this experiment we enlisted some undergraduate students, some graduate students, and some investment bankers who had come to the campus to recruit new employees for their firms. Once the experiment started we presented our participants with three different sounds, and following each, asked them if they would be willing to get paid a particular amount of money (which served as the price anchor) for hearing those sounds again. One sound was a 30-second high-pitched 3,000-hertz sound, somewhat like someone screaming in a high-pitched voice. Another was a 30-second full-spectrum noise (also called white noise), which is similar to the noise a television set makes when there is no reception. The third was a 30-second oscillation between high-pitched and low-pitched sounds. (I am not sure if the bankers understood exactly what they were about to experience, but maybe even our annoying sounds were less annoying than talking about investment banking.)

We used sounds because there is no existing market for annoying sounds (so the participants couldn’t use a market price as a way to think about the value of these sounds). We also used annoying sounds, specifically, because no one likes such sounds (if we had used classical music, some would have liked it better than others). As for the sounds themselves, I selected them after creating hundreds of sounds, choosing these three because they were, in my opinion, equally annoying.

We placed our participants in front of computer screens at the lab, and had them clamp headphones over their ears.

As the room quieted down, the first group saw this message appear in front of them: “In a few moments we are going to play a new unpleasant tone over your headset. We are interested in how annoying you find it. Immediately after you hear the tone, we will ask you whether, hypothetically, you would be willing to repeat the same experience in exchange for a payment of 10 cents.” The second group got the same message, only with an offer of 90 cents rather than 10 cents.

Would the anchor prices make a difference? To find out, we turned on the sound—in this case the irritating 30-second, 3,000-hertz squeal. Some of our participants grimaced. Others rolled their eyes.

When the screeching ended, each participant was presented with the anchoring question, phrased as a hypothetical choice: Would the participant be willing, hypothetically, to repeat the experience for a cash payment (which was 10 cents for the first group and 90 cents for the second group)? After answering this anchoring question, the participants were asked to indicate on the computer screen the lowest price they would demand to listen to the sound again. This decision was real, by the way, as it would determine whether they would hear the sound again—and get paid for doing so.*

Soon after the participants entered their prices, they learned the outcome. Participants whose price was sufficiently low “won” the sound, had the (unpleasant) opportunity to hear it again, and got paid for doing so. The participants whose price was too high did not listen to the sound and were not paid for this part of the experiment.

What was the point of all this? We wanted to find out whether the first prices that we suggested (10 cents and 90 cents) had served as an anchor. And indeed they had. Those who first faced the hypothetical decision about whether to listen to the sound for 10 cents needed much less money to be willing to listen to this sound again (33 cents on average) relative to those who first faced the hypothetical decision about whether to listen to the sound for 90 cents—this second group demanded more than twice the compensation (73 cents on average) for the same annoying experience. Do you see the difference that the suggested price had?

BUT THIS WAS only the start of our exploration. We also wanted to know how influential the anchor would be in future decisions. Suppose we gave the participants an opportunity to drop this anchor and run for another? Would they do it? To put it in terms of goslings, would they swim across the pond after their original imprint and then, midway, swing their allegiance to a new mother goose? In terms of goslings, I think you know that they would stick with the original mom. But what about humans? The next two phases of the experiment would enable us to answer these questions.