Полная версия

The Irrational Bundle

So what was going on here? Let me start with a fundamental observation: most people don’t know what they want unless they see it in context. We don’t know what kind of racing bike we want—until we see a champ in the Tour de France ratcheting the gears on a particular model. We don’t know what kind of speaker system we like—until we hear a set of speakers that sounds better than the previous one. We don’t even know what we want to do with our lives—until we find a relative or a friend who is doing just what we think we should be doing. Everything is relative, and that’s the point. Like an airplane pilot landing in the dark, we want runway lights on either side of us, guiding us to the place where we can touch down our wheels.

In the case of the Economist, the decision between the Internet-only and print-only options would take a bit of thinking. Thinking is difficult and sometimes unpleasant. So the Economist’s marketers offered us a no-brainer: relative to the print-only option, the print-and-Internet option looks clearly superior.

The geniuses at the Economist aren’t the only ones who understand the importance of relativity. Take Sam, the television salesman. He plays the same general type of trick on us when he decides which televisions to put together on display:

36-inch Panasonic for $690

42-inch Toshiba for $850

50-inch Philips for $1,480

Which one would you choose? In this case, Sam knows that customers find it difficult to compute the value of different options. (Who really knows if the Panasonic at $690 is a better deal than the Philips at $1,480?) But Sam also knows that given three choices, most people will take the middle choice (as in landing your plane between the runway lights). So guess which television Sam prices as the middle option? That’s right—the one he wants to sell!

Of course, Sam is not alone in his cleverness. The New York Times ran a story recently about Gregg Rapp, a restaurant consultant, who gets paid to work out the pricing for menus. He knows, for instance, how lamb sold this year as opposed to last year; whether lamb did better paired with squash or with risotto; and whether orders decreased when the price of the main course was hiked from $39 to $41.

One thing Rapp has learned is that high-priced entrées on the menu boost revenue for the restaurant—even if no one buys them. Why? Because even though people generally won’t buy the most expensive dish on the menu, they will order the second most expensive dish. Thus, by creating an expensive dish, a restaurateur can lure customers into ordering the second most expensive choice (which can be cleverly engineered to deliver a higher profit margin).1

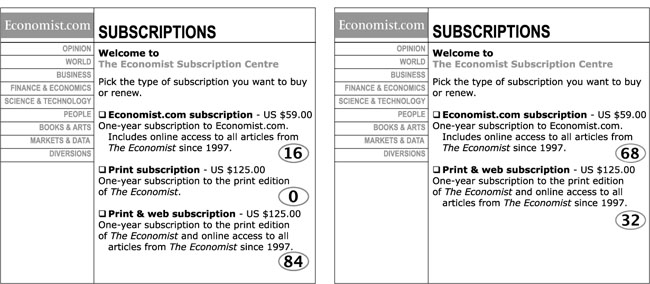

SO LET’S RUN through the Economist’s sleight of hand in slow motion.

As you recall, the choices were:

1. Internet-only subscription for $59.

2. Print-only subscription for $125.

3. Print-and-Internet subscription for $125.

When I gave these options to 100 students at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, they opted as follows:

1. Internet-only subscription for $59—16 students

2. Print-only subscription for $125—zero students

3. Print-and-Internet subscription for $125—84 students

So far these Sloan MBAs are smart cookies. They all saw the advantage in the print-and-Internet offer over the print-only offer. But were they influenced by the mere presence of the print-only option (which I will henceforth, and for good reason, call the “decoy”). In other words, suppose that I removed the decoy so that the choices would be the ones seen in the figure below:

Would the students respond as before (16 for the Internet only and 84 for the combination)?

Certainly they would react the same way, wouldn’t they? After all, the option I took out was one that no one selected, so it should make no difference. Right?

Au contraire! This time, 68 of the students chose the Internet-only option for $59, up from 16 before. And only 32 chose the combination subscription for $125, down from 84 before.*

What could have possibly changed their minds? Nothing rational, I assure you. It was the mere presence of the decoy that sent 84 of them to the print-and-Internet option (and 16 to the Internet-only option). And the absence of the decoy had them choosing differently, with 32 for print-and-Internet and 68 for Internet-only.

This is not only irrational but predictably irrational as well. Why? I’m glad you asked.

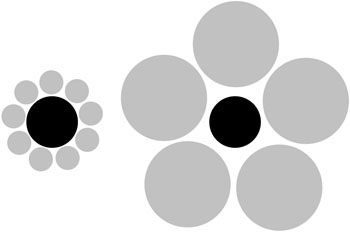

LET ME OFFER you this visual demonstration of relativity.

As you can see, the middle circle can’t seem to stay the same size. When placed among the larger circles, it gets smaller. When placed among the smaller circles, it grows bigger. The middle circle is the same size in both positions, of course, but it appears to change depending on what we place next to it.

This might be a mere curiosity, but for the fact that it mirrors the way the mind is wired: we are always looking at the things around us in relation to others. We can’t help it. This holds true not only for physical things—toasters, bicycles, puppies, restaurant entrées, and spouses—but for experiences such as vacations and educational options, and for ephemeral things as well: emotions, attitudes, and points of view.

We always compare jobs with jobs, vacations with vacations, lovers with lovers, and wines with wines. All this relativity reminds me of a line from the film Crocodile Dundee, when a street hoodlum pulls a switchblade against our hero, Paul Hogan. “You call that a knife?” says Hogan incredulously, withdrawing a bowie blade from the back of his boot. “Now this,” he says with a sly grin, “is a knife.”

RELATIVITY IS (RELATIVELY) easy to understand. But there’s one aspect of relativity that consistently trips us up. It’s this: we not only tend to compare things with one another but also tend to focus on comparing things that are easily comparable—and avoid comparing things that cannot be compared easily.

That may be a confusing thought, so let me give you an example. Suppose you’re shopping for a house in a new town. Your real estate agent guides you to three houses, all of which interest you. One of them is a contemporary, and two are colonials. All three cost about the same; they are all equally desirable; and the only difference is that one of the colonials (the “decoy”) needs a new roof and the owner has knocked a few thousand dollars off the price to cover the additional expense.

So which one will you choose?

The chances are good that you will not choose the contemporary and you will not choose the colonial that needs the new roof, but you will choose the other colonial. Why? Here’s the rationale (which is actually quite irrational). We like to make decisions based on comparisons. In the case of the three houses, we don’t know much about the contemporary (we don’t have another house to compare it with), so that house goes on the sidelines. But we do know that one of the colonials is better than the other one. That is, the colonial with the good roof is better than the one with the bad roof. Therefore, we will reason that it is better overall and go for the colonial with the good roof, spurning the contemporary and the colonial that needs a new roof.

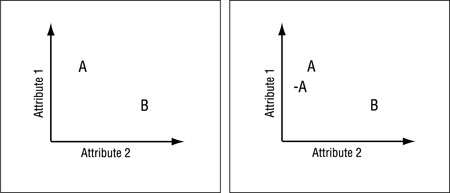

To better understand how relativity works, consider the following illustration:

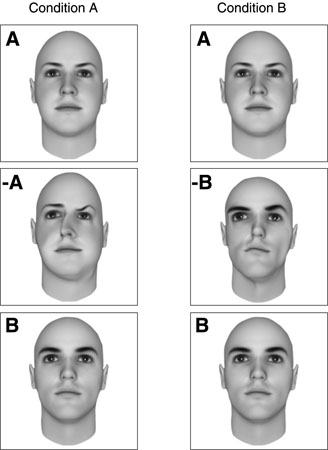

In the left side of this illustration we see two options, each of which is better on a different attribute. Option (A) is better on attribute 1—let’s say quality. Option (B) is better on attribute 2—let’s say beauty. Obviously these are two very different options and the choice between them is not simple. Now consider what happens if we add another option, called (–A) (see the right side of the illustration). This option is clearly worse than option (A), but it is also very similar to it, making the comparison between them easy, and suggesting that (A) is not only better than (–A) but also better than (B).

In essence, introducing (–A), the decoy, creates a simple relative comparison with (A), and hence makes (A) look better, not just relative to (–A), but overall as well. As a consequence, the inclusion of (–A) in the set, even if no one ever selects it, makes people more likely to make (A) their final choice.

Does this selection process sound familiar? Remember the pitch put together by the Economist? The marketers there knew that we didn’t know whether we wanted an Internet subscription or a print subscription. But they figured that, of the three options, the print-and-Internet combination would be the offer we would take.

Here’s another example of the decoy effect. Suppose you are planning a honeymoon in Europe. You’ve already decided to go to one of the major romantic cities and have narrowed your choices to Rome and Paris, your two favorites. The travel agent presents you with the vacation packages for each city, which includes airfare, hotel accommodations, sightseeing tours, and a free breakfast every morning. Which would you select?

For most people, the decision between a week in Rome and a week in Paris is not effortless. Rome has the Coliseum; Paris, the Louvre. Both have a romantic ambience, fabulous food, and fashionable shopping. It’s not an easy call. But suppose you were offered a third option: Rome without the free breakfast, called -Rome or the decoy.

If you were to consider these three options (Paris, Rome, -Rome), you would immediately recognize that whereas Rome with the free breakfast is about as appealing as Paris with the free breakfast, the inferior option, which is Rome without the free breakfast, is a step down. The comparison between the clearly inferior option (-Rome) makes Rome with the free breakfast seem even better. In fact, -Rome makes Rome with the free breakfast look so good that you judge it to be even better than the difficult-to-compare option, Paris with the free breakfast.

ONCE YOU SEE the decoy effect in action, you realize that it is the secret agent in more decisions than we could imagine. It even helps us decide whom to date—and, ultimately, whom to marry. Let me describe an experiment that explored just this subject.

As students hurried around MIT one cold weekday, I asked some of them whether they would allow me to take their pictures for a study. In some cases, I got disapproving looks. A few students walked away. But most of them were happy to participate, and before long, the card in my digital camera was filled with images of smiling students. I returned to my office and printed 60 of them—30 of women and 30 of men.

The following week I made an unusual request of 25 of my undergraduates. I asked them to pair the 30 photographs of men and the 30 of women by physical attractiveness (matching the men with other men, and the women with other women). That is, I had them pair the Brad Pitts and the George Clooneys of MIT, as well as the Woody Allens and the Danny DeVitos (sorry, Woody and Danny). Out of these 30 pairs, I selected the six pairs—three female pairs and three male pairs—that my students seemed to agree were most alike.

Now, like Dr. Frankenstein himself, I set about giving these faces my special treatment. Using Photoshop, I mutated the pictures just a bit, creating a slightly but noticeably less attractive version of each of them. I found that just the slightest movement of the nose threw off the symmetry. Using another tool, I enlarged one eye, eliminated some of the hair, and added traces of acne.

No flashes of lightning illuminated my laboratory; nor was there a baying of the hounds on the moor. But this was still a good day for science. By the time I was through, I had the MIT equivalent of George Clooney in his prime (A) and the MIT equivalent of Brad Pitt in his prime (B), and also a George Clooney with a slightly drooping eye and thicker nose (–A, the decoy) and a less symmetrical version of Brad Pitt (-B, another decoy). I followed the same procedure for the less attractive pairs. I had the MIT equivalent of Woody Allen with his usual lopsided grin (A) and Woody Allen with an unnervingly misplaced eye (–A), as well as Danny DeVito (B) and a slightly disfigured version of Danny DeVito (–B).

For each of the 12 photographs, in fact, I now had a regular version as well as an inferior (–) decoy version. (See the illustration for an example of the two conditions used in the study.)

It was now time for the main part of the experiment. I took all the sets of pictures and made my way over to the student union. Approaching one student after another, I asked each to participate. When the students agreed, I handed them a sheet with three pictures (as in the illustration here). Some of them had the regular picture (A), the decoy of that picture (–A), and the other regular picture (B). Others had the regular picture (B), the decoy of that picture (–B), and the other regular picture (A).

For example, a set might include a regular Clooney (A), a decoy Clooney (–A), and a regular Pitt (B); or a regular Pitt (B), a decoy Pitt (–B), and a regular Clooney (A). After selecting a sheet with either male or female pictures, according to their preferences, I asked the students to circle the people they would pick to go on a date with, if they had a choice. All this took quite a while, and when I was done, I had distributed 600 sheets.

What was my motive in all this? Simply to determine if the existence of the distorted picture (–A or –B) would push my participants to choose the similar but undistorted picture. In other words, would a slightly less attractive George Clooney (–A) push the participants to choose the perfect George Clooney over the perfect Brad Pitt?

There were no pictures of Brad Pitt or George Clooney in my experiment, of course. Pictures (A) and (B) showed ordinary students. But do you remember how the existence of a colonial-style house needing a new roof might push you to choose a perfect colonial over a contemporary house—simply because the decoy colonial would give you something against which to compare the regular colonial? And in the Economist’s ad, didn’t the print-only option for $125 push people to take the print-and-Internet option for $125? Similarly, would the existence of a less perfect person (–A or –B) push people to choose the perfect one (A or B), simply because the decoy option served as a point of comparison?

Note: For this illustration, I used computerized faces, not those of the MIT students. And of course, the letters did not appear on the original sheets.

It did. Whenever I handed out a sheet that had a regular picture, its inferior version, and another regular picture, the participants said they would prefer to date the “regular” person—the one who was similar, but clearly superior, to the distorted version—over the other, undistorted person on the sheet. This was not just a close call—it happened 75 percent of the time.

To explain the decoy effect further, let me tell you something about bread-making machines. When Williams-Sonoma first introduced a home “bread bakery” machine (for $275), most consumers were not interested. What was a home bread-making machine, anyway? Was it good or bad? Did one really need home-baked bread? Why not just buy a fancy coffeemaker sitting nearby instead? Flustered by poor sales, the manufacturer of the bread machine brought in a marketing research firm, which suggested a fix: introduce an additional model of the bread maker, one that was not only larger but priced about 50 percent higher than the initial machine.

Now sales began to rise (along with many loaves of bread), though it was not the large bread maker that was being sold. Why? Simply because consumers now had two models of bread makers to choose from. Since one was clearly larger and much more expensive than the other, people didn’t have to make their decision in a vacuum. They could say: “Well, I don’t know much about bread makers, but I do know that if I were to buy one, I’d rather have the smaller one for less money.” And that’s when bread makers began to fly off the shelves.2

OK for bread makers. But let’s take a look at the decoy effect in a completely different situation. What if you are single, and hope to appeal to as many attractive potential dating partners as possible at an upcoming singles event? My advice would be to bring a friend who has your basic physical characteristics (similar coloring, body type, facial features), but is slightly less attractive (–you).

Why? Because the folks you want to attract will have a hard time evaluating you with no comparables around. However, if you are compared with a “–you,” the decoy friend will do a lot to make you look better, not just in comparison with the decoy but also in general, and in comparison with all the other people around. It may sound irrational (and I can’t guarantee this), but the chances are good that you will get some extra attention. Of course, don’t just stop at looks. If great conversation will win the day, be sure to pick a friend for the singles event who can’t match your smooth delivery and rapier wit. By comparison, you’ll sound great.

Now that you know this secret, be careful: when a similar but better-looking friend of the same sex asks you to accompany him or her for a night out, you might wonder whether you have been invited along for your company or merely as a decoy.

RELATIVITY HELPS US make decisions in life. But it can also make us downright miserable. Why? Because jealousy and envy spring from comparing our lot in life with that of others.

It was for good reason, after all, that the Ten Commandments admonished, “Neither shall you desire your neighbor’s house nor field, or male or female slave, or donkey or anything that belongs to your neighbor.” This might just be the toughest commandment to follow, considering that by our very nature we are wired to compare.

Modern life makes this weakness even more pronounced. A few years ago, for instance, I met with one of the top executives of one of the big investment companies. Over the course of our conversation he mentioned that one of his employees had recently come to him to complain about his salary.

“How long have you been with the firm?” the executive asked the young man.

“Three years. I came straight from college,” was the answer.

“And when you joined us, how much did you expect to be making in three years?”

“I was hoping to be making about a hundred thousand.”

The executive eyed him curiously.

“And now you are making almost three hundred thousand, so how can you possibly complain?” he asked.

“Well,” the young man stammered, “it’s just that a couple of the guys at the desks next to me, they’re not any better than I am, and they are making three hundred ten.”

The executive shook his head.

An ironic aspect of this story is that in 1993, federal securities regulators forced companies, for the first time, to reveal details about the pay and perks of their top executives. The idea was that once pay was in the open, boards would be reluctant to give executives outrageous salaries and benefits. This, it was hoped, would stop the rise in executive compensation, which neither regulation, legislation, nor shareholder pressure had been able to stop. And indeed, it needed to stop: in 1976 the average CEO was paid 36 times as much as the average worker. By 1993, the average CEO was paid 131 times as much.

But guess what happened. Once salaries became public information, the media regularly ran special stories ranking CEOs by pay. Rather than suppressing the executive perks, the publicity had CEOs in America comparing their pay with that of everyone else. In response, executives’ salaries skyrocketed. The trend was further “helped” by compensation consulting firms (scathingly dubbed “Ratchet, Ratchet, and Bingo” by the investor Warren Buffett) that advised their CEO clients to demand outrageous raises. The result? Now the average CEO makes about 369 times as much as the average worker—about three times the salary before executive compensation went public.

Keeping that in mind, I had a few questions for the executive I met with.

“What would happen,” I ventured, “if the information in your salary database became known throughout the company?”

The executive looked at me with alarm. “We could get over a lot of things here—insider trading, financial scandals, and the like—but if everyone knew everyone else’s salary, it would be a true catastrophe. All but the highest-paid individual would feel underpaid—and I wouldn’t be surprised if they went out and looked for another job.”

Isn’t this odd? It has been shown repeatedly that the link between amount of salary and happiness is not as strong as one would expect it to be (in fact, it is rather weak). Studies even find that countries with the “happiest” people are not among those with the highest personal income. Yet we keep pushing toward a higher salary. Much of that can be blamed on sheer envy. As H. L. Mencken, the twentieth-century journalist, satirist, social critic, cynic, and freethinker noted, a man’s satisfaction with his salary depends on (are you ready for this?) whether he makes more than his wife’s sister’s husband. Why the wife’s sister’s husband? Because (and I have a feeling that Mencken’s wife kept him fully informed of her sister’s husband’s salary) this is a comparison that is salient and readily available.*

All this extravagance in CEOs’ pay has had a damaging effect on society. Instead of causing shame, every new outrage in compensation encourages other CEOs to demand even more. “In the Web World,” according to a headline in the New York Times, the “Rich Now Envy the Superrich.”

In another news story, a physician explained that he had graduated from Harvard with the dream of someday receiving a Nobel Prize for cancer research. This was his goal. This was his dream. But a few years later, he realized that several of his colleagues were making more as medical investment advisers at Wall Street firms than he was making in medicine. He had previously been happy with his income, but hearing of his friends’ yachts and vacation homes, he suddenly felt very poor. So he took another route with his career—the route of Wall Street.3 By the time he arrived at his twentieth class reunion, he was making 10 times what most of his peers were making in medicine. You can almost see him, standing in the middle of the room at the reunion, drink in hand—a large circle of influence with smaller circles gathering around him. He had not won the Nobel Prize, but he had relinquished his dreams for a Wall Street salary, for a chance to stop feeling “poor.” Is it any wonder that family practice physicians, who make an average of $160,000 a year, are in short supply?*

CAN WE DO anything about this problem of relativity?

The good news is that we can sometimes control the “circles” around us, moving toward smaller circles that boost our relative happiness. If we are at our class reunion, and there’s a “big circle” in the middle of the room with a drink in his hand, boasting of his big salary, we can consciously take several steps away and talk with someone else. If we are thinking of buying a new house, we can be selective about the open houses we go to, skipping the houses that are above our means. If we are thinking about buying a new car, we can focus on the models that we can afford, and so on.

We can also change our focus from narrow to broad. Let me explain with an example from a study conducted by two brilliant researchers, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. Suppose you have two errands to run today. The first is to buy a new pen, and the second is to buy a suit for work. At an office supply store, you find a nice pen for $25. You are set to buy it, when you remember that the same pen is on sale for $18 at another store 15 minutes away. What would you do? Do you decide to take the 15-minute trip to save the $7? Most people faced with this dilemma say that they would take the trip to save the $7.