Полная версия

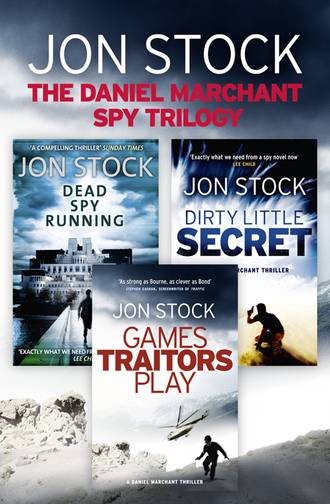

The Daniel Marchant Spy Trilogy: Dead Spy Running, Games Traitors Play, Dirty Little Secret

‘An asset? Am I missing something here? Right now, Salim Dhar’s our new Ace of Spades.’

‘Sir, we think he could be turned.’ Carter looked back again nervously. Fielding gave the discreetest of nods.

‘Is that right?’

‘MI6 have turned up some interesting CX on Dhar,’ Carter continued.

‘Will, we think he might be one of ours,’ Fielding said, acknowledging Carter, who had drawn enough of the Director’s fire. He would take it up from here.

‘You think?’

‘Stephen Marchant set up a retainer for his family back in 1980, when he was posted to Delhi.’

‘Christ, Marcus, why didn’t you mention this sooner?’

Fielding pointedly ignored the question. ‘Monthly payments to his father, following his dismissal from the British High Commission.’

‘Didn’t he once work at our embassy?’

‘For a number of years, yes.’

‘So why was Marchant paying him? Dhar was just a kid.’

‘I know.’ It was the one question Fielding didn’t have an answer to.

‘But you think this makes Dhar a good guy, rather than confirming our worst fears about Stephen Marchant? Forgive the Monday-morning quarterbacking, but from our point of view this doesn’t exactly look like asset cash well spent: two US Embassy attacks, the London Marathon.’

‘No one’s saying he’s ours, sir,’ Carter said. ‘But we think he might be persuaded to work for the British.’

‘And Daniel Marchant is the only person who can find out,’ Fielding added. ‘Dhar would be the highest ranking member of AQ the West has ever run. We’d be prepared to pool on this one.’

There was another pause, and for a moment Fielding thought the link with Langley had dropped. But he knew the plan would appeal to the clandestine streak that ran deep in the Director.

‘I can’t have Marchant and Dhar running around India when the President arrives. The DNI just wouldn’t buy it. And I wouldn’t blame him.’ He paused again. ‘You’ve got twenty-four to figure out which side Dhar’s on, then we’re bringing them both in.’

The two women, Kirsty and Holly, had tickets for three-tier A/C on the Mangala Express, which was considerably more comfortable than Marchant’s bare-benched economy carriage. Their entire compartment was open plan, but it was loosely divided up into separate areas by curtains. The lights had already been turned down, even though Delhi was only an hour behind them, and the atmosphere was like that of a well-behaved school dormitory, a faint murmur of snoring rising above the rattle of the wheels. Marchant’s carriage, by contrast, was a seething mass of people who were clearly intent on eating, burping and arguing all the way to Kerala, 1,500 miles south. There were no beds, just hard wooden seats.

The two women’s area consisted of a pair of three-tier bunks facing each other. They were sleeping on the top two bunks, and a Keralan family, with one child, occupied the lower decks. The bunk directly below Holly was empty, and it was on this that Marchant was now lying, talking up to Kirsty.

‘You can stay there the night, if you want to,’ she said, glancing across at Holly. ‘She’s already asleep. There were three of us, but Holly and Anya had a bit of a falling out, so Anya stayed in Delhi. You’re on her bed.’

‘I’ll see if the ticket guy’ll upgrade me,’ Marchant said. He could hear the inspector making his way down the carriage. Earlier, a member of staff had eyed him suspiciously while he distributed sheets and blankets around the carriage.

Holly and Kirsty, both English and in their early twenties, were going to Goa. They were on a six-month world tour and had been travelling in India for two weeks. Holly, the younger one, was already at war with the subcontinent, railing at its food, the weather, the men, her bowel movements and the state of the public lavatories, before falling asleep. The argument at the station had clearly exhausted her. Kirsty had a more relaxed manner, and was obsessed with neither the weather nor her bowels. Something about her laid-back approach to life reminded Marchant of Monika, and they had immediately hit it off.

‘D’you hear that?’ Kirsty asked, nodding down the carriage. Marchant listened as someone protested about not being allowed to stay in an empty seat. The inspector explained about waiting lists, three-month advance bookings, the police. Marchant’s and Kirsty’s eyes met.

‘Quick, come up here. You can hide under my blanket.’

Marchant looked below him. The man from Kerala, an engineer who had earlier given him his business card, was snoring. The woman was also sleeping, but the toddler, who was cradled next to her, had his big brown eyes open and was staring up at him. Marchant smiled, putting a finger to his lips. ‘Sshhh,’ he said, stretching his leg across onto the edge of the opposite bunk, where the Keralan family had stowed some of their luggage. Then he heaved himself up onto the narrow top bunk. Kirsty giggled as she shuffled across to the edge, trying to make some room for Marchant beside the wall.

‘They’re tiny, these beds,’ Marchant whispered, feeling her body warmth as he pulled the wool blanket over him. Its coarseness reminded him of school.

‘The man’s coming,’ Kirsty said, pulling her rucksack up from her feet to provide a screen. Marchant lay still, listening out for the ticket collector. He heard him stir the family below as Kirsty reached across to wake Holly.

When the inspector had gone, Marchant stayed where he was for a few moments, lulled by the carriage’s rhythmic motion. The last time he had been on a train in India, in his gap year, he had travelled to Calcutta on what had once been known as the Frontier Mail.

‘David?’ Kirsty said quietly. ‘He’s gone now.’ Marchant came up for air, and the two of them lay there, looking up at the metallic-blue 1950s interior, with its rivets, brass switches and bakelite fittings. The style reminded Marchant of the inside of an old naval ship.

Earlier, they had talked about the incident on the Delhi concourse. Both women thanked him for his gallant rescue, asking if any of what he said had been true. Marchant chose to maintain the deceit, a harmless one for once, and told them that he had spent two days working as an extra up at the Red Fort, and that Shah Rukh was shorter in the flesh. He needed to keep his liar’s hand in.

Holly had sensed the chemistry between Marchant and Kirsty, and had retreated to her bunk in a sulk, leaving the two of them to sit on the open doorstep of the train, watching Delhi’s suburbs slide by. Their conversation had been unforced, as if they had known each other for years. No questions or accounting for lives, which suited Marchant.

He learnt little about Kirsty, except that she wanted to practise Ashtanga on a beach in Goa, and had the lissom figure of a yoga babe. All Kirsty thought she knew about him was that his name was David Marlowe, his rucksack had been stolen from a guesthouse in Paharganj, and he was originally from Ireland. They were strangers, in other words–much more so than Kirsty would ever know.

But Marchant felt there was something about their carefree encounter, lying on the narrow top bunk bed of a night train to Goa, listening to the long, droning horn of the engine, somewhere far ahead of them, that made it inevitable she should link a leg over his. He was about to reciprocate the gesture when, below them, the child from Kerala coughed. Marchant smiled as Kirsty moved her leg away. Instead, they lay there together, their colliding worlds moving apart from each other again, as the Mangala Express pushed on through the darkness towards the Arabian Sea.

34

Paul Myers had been drinking heavily all evening in the Morpeth Arms, watching the lights of Legoland across the Thames burning brightly into the night. He knew that what he was about to do could lead to his dismissal. It was also a betrayal of Leila, one of the few people he had been able to call a friend. But she had betrayed him, and he now realised that he was left with little option. Draining his fifth pint of London Pride, he stood up and walked outside, making his way across the Embankment to the pavement by the river.

He watched the dark water running silently beneath him as he dialled the personal mobile of Marcus Fielding. Very few people knew the number, and even fewer were allowed to ring it. But when you worked at GCHQ, with the security clearance of a senior intelligence analyst, there were ways. Myers looked up at the Vicar’s office as the number began to ring.

‘Who’s this?’ Fielding said.

‘Paul Myers, senior analyst, Asia desk, Cheltenham,’ Myers said, aware of a slight slurring of his words.

‘This is neither an appropriate channel of communication, nor an appropriate time,’ Fielding said. ‘Who do you report to?’

‘Sir, it’s about Leila. I need to speak to you tonight.’ Despite the alcohol, Myers detected a missed beat at the other end of the phone. ‘We’ve intercepted some of her calls. I think you should see the transcripts. I’ve got them with me.’

A pause. ‘Where are you?’

‘Just across the water.’ Myers glanced up at the buttressed bay window at the top of Legoland. He couldn’t see anyone, but imagined the Vicar looking out into the darkness.

‘I’ll pick you up in my car,’ Fielding said. ‘I’m on my way out.’

Ten minutes later, Myers was in the back of a Range Rover, next to Fielding, as they were driven down the Thames towards Westminster. Myers was much as Fielding had imagined: few social skills, heavy-rimmed glasses, little personal hygiene, drink problem, and an IQ off the scale. A typical Cheltenham data cruncher, in other words.

‘The first call showed up on the grid a few hours after the marathon,’ Myers said. ‘We were listening to everything, desperate for a lead. It was mayhem, a bit like 7/7. South India was obviously in the frame, so we were scanning for Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu. But we were on the lookout for Farsi, too. I picked up this. I knew it was Leila’s voice straight away.’

He passed Fielding a printout of a phone transcript. Fielding read it through carefully.

Mother (Farsi): ‘They came tonight, three of them. They took the boy–you know him, the one who cooks for me. Beat him in front of my eyes.’

Leila (Farsi): ‘Did they hurt you, Mama? Did they touch you?’

Mother (Farsi): ‘He was like a grandson to me. Dragged him away by his [feet?].’

Leila (Farsi): ‘Mama, what did they do to you?’

Mother (Farsi): ‘You told me they wouldn’t come. Others here have suffered, too.’

Leila: ‘Never again, Mama. They won’t come any more. (English) I promise.’

Mother (Farsi): ‘Why did they say my family are to blame? What have we ever done to them?’

Leila (English): ‘Nothing. (Farsi) You know how it is. Are you safe now?’

[Line dropped.]

Fielding passed the transcript back.

‘Did you log this, give it to anyone else?’

Myers was silent for a moment, bobbing his head. ‘No. I know I should have done. Leila and I were friends. Good friends. I thought nothing of it. She had talked to me before about the nursing home, the way the staff mistreated her mother. To be honest, I felt a little awkward listening in. Felt like family business.’

‘What made you change your mind?’

‘Well obviously the news that she was working for the Americans. I hated her for that when I heard. It felt very personal, a personal betrayal. I went back to the transcript, read it through again.’

‘And?’

‘I’d overlooked the most important part of it, the transmission data. Leila had always talked about her mother as if she was in a nursing home in Britain. When I heard her talking about a cook, the beating, I assumed it was just about the nursing staff. The call had been made to a UK mobile number, but I checked back through the intercept log and realised that it had been routed via a mobile network in Tehran.’

They had all missed it, Fielding thought. Everyone except the Americans, who had not only learnt that Leila’s mother had moved to Iran, but had used that information to turn Leila. More worryingly, it meant that the Developed Vetting system had failed, the first casualty of the Service’s new policy of casting its recruitment net wider. How many more would slip through in the future?

‘We used to look out for each other,’ Myers continued.

‘In what way?’

‘The odd thing, here and there.’

‘Go on.’

‘At Cheltenham we heard some chatter on the morning of the marathon. I passed it on, told her to be careful.’

‘Did you tell anyone else?’

‘No. At the time I thought it was nothing. I just knew she was running. She thanked me, said she would pass it up the line, but I know she never did.’

‘And you think that’s important now?’

‘Yeah, I do.’

‘Why?’

‘My line manager recently received instructions from MI6 to focus solely on the Gulf. We picked this up on today’s grid. It’s from a phone booth in Delhi. Leila’s voice again. I’ve run it through profiling. She’s trying to talk to her mother–in Tehran.’

He handed Fielding another transcript.

Leila (Farsi): ‘Mama. It’s Leila. Things will be better soon.’

Unidentified Male (Farsi): ‘Your mother’s in hospital.’

Leila: ‘Who is this?’

Unidentified male: ‘A friend of the family. [Male voices in background] She’s fine and, inshallah, will have the best treatment dollars can buy.’

Leila: ‘I want her looked after, that was always the deal.’

Unidentified male: ‘I will tell her you called. And that her health rests in your hands.’

[End]

‘Do we know who the male voice is?’ Fielding asked, passing the transcript back.

Myers paused. ‘Ali Mousavi, a senior officer in VEVAK, the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence and Security.’

‘I know him,’ Fielding said. ‘Takes personal pleasure in persecuting Bahá’ís.’

‘Does he also enjoy masterminding marathon attacks?’

‘Why?’

‘I’ve listened again to the chatter I picked up that night, before the race. All we got was one side of a conversation, London end. South Indian accent, clean mobile.’ Myers handed Fielding another transcript. ‘But the call came out of Iran. This afternoon I finally managed to trace the phone. It was used once earlier this year by Ali Mousavi.’

Fielding looked up at Myers. Like everything in intelligence, it wasn’t conclusive, but it was enough for him. He read the transcript:

Unidentified male (English, South Indian accent): 35,000 runners.

Caller: [no data, encrypted, out of Iran]

Unidentified male: Acha. 8 minutes 30.

[End]

Fielding asked for the other two transcripts back, and studied them again.

‘Thank you for showing me these,’ he said, sifting through the pages. ‘I appreciate the risk.’

‘We heard that the Americans were paying for Leila’s mother’s healthcare in return for her working for them. Her mother was a Bahá’í, so they were more than happy to support her.’

‘That’s what we heard, too.’

‘VEVAK believe all Bahá’ís are Zionist agents, get wind of this, turn up at her mother’s house, answer Leila’s call when she rings.’

‘That would be the logical explanation. But if the arrangement between Leila and the Americans was secret, as we must assume it was, then why would she say to an unknown Iranian who answers the phone in her mother’s house: “I want her looked after, that was always the deal”?’

Myers sat quite still, staring at the footwell of the car. For a moment Fielding thought he was going to be sick. Then he looked up and turned towards Fielding.

‘Leila wasn’t working for the Americans, was she?’

‘No, she wasn’t.’

‘And there wasn’t an American mole in MI6.’

‘No. There wasn’t. There was an Iranian one, who is now working for the CIA in Delhi, seventy-two hours before the new US President touches down. I think I need to drop you off.’

35

Marchant heard the police before they reached his carriage. He lay there, eyes open, Kirsty by his side, listening to the sounds of sleep all around him. In the background he could detect the faint but urgent voices of authority. He disentangled himself from Kirsty’s limp embrace and swung down to the floor of the carriage, making sure his footfall was silent. He knew he had to move quickly. Police were working their way through the train from both ends.

Marchant stepped out of the sleeping area and into a small space at the end of the carriage, where it was joined to the next one. In a cubicle marked ‘Laundry’, a junior-looking train official slept on a fold-down bed, pillows and blankets stacked neatly on shelves above him. The door was ajar. Quietly, Marchant pulled it closed. Then he pushed down on the handle of the outside door and swung it open. The night air was warm, the surrounding countryside flat: paddy fields. Marchant estimated that the train was travelling at 30 mph–not quick, but too fast to jump.

Beside him was a small metal cupboard marked ‘Electrics’. He pulled at its dented front panel. The lock had long since broken, and it opened easily. Voices were now getting louder behind him. He looked up and down the train, then flicked all those switches in the cupboard that were in the up position. Two lights above him went out, along with the dim night lights in the main carriage. It would buy him a few seconds. Checking that no emergency lighting had come on, he stretched down onto the step outside the train’s open door, holding onto the handle beside it. He then put his left foot up onto the door, and lifted himself upwards, glancing at the printed list of passengers that had been glued to the outside of the train in Delhi: name, sex, age.

For a moment, suspended horizontally above the moving ground, he thought he was going to fall, but with his left hand he managed to grip the top of the door, and pulled himself up further. A second later, the train passed a concrete signal post, which brushed against his billowing shirt. The surge of adrenalin made his legs heavy, and he knew he was losing strength.

Glancing both ways, he grabbed onto the lip of the train’s roof, then lifted himself upwards again, pushing with one foot on the small light above the passenger list. The next moment he was lying flat on the roof. He thought of Shah Rukh Khan dancing on the top of a train in Dil Se, but he didn’t feel like a film star as he pressed himself against the dirty train roof, looking out for bridges.

He knew he wasn’t safe yet. Leaning over the side of the train, he grabbed the heavy door and swung it shut. The door clicked closed, but not properly. There was no time to push it flush with the side of the carriage. He started to shuffle back down the roof of the train, towards economy class, keeping his body as flat as he could.

Below him, a posse of policemen entered the carriage from the far end, making their way through the sleeping families, looking for someone. They didn’t disturb passengers unless they couldn’t see their faces. When they reached Kirsty’s and Holly’s cubicle, the policeman in charge deferred to a female colleague, who moved forward. Holly’s face was clearly visible, but Kirsty’s was hidden beneath her blanket.

‘Yes please, wake up madam, we need to see your passport,’ the policewoman said, tugging on Kirsty’s blanket. She then spoke to Holly, whose eyes had opened. ‘Passport, madam? Police check.’

Holly sat up and fumbled sleepily through her rucksack, which was at the end of her bed. ‘Kirsty, wake up,’ she called across to her friend, who was still asleep. ‘Kirsty?’

Kirsty stirred, blinking at the policewoman, whose head was just below the level of her bunk. Instinctively, she turned to where Marchant had been lying, and then looked back at the woman.

‘Lost something?’ she said to Kirsty.

‘Just my bag.’

‘Is this it?’ the policewoman said, tapping the rucksack at Kirsty’s feet.

Kirsty nodded, then pulled out her passport from the money belt around her waist, sweeping back her hair, still half asleep. Where had David gone? She hadn’t heard him leave. As the woman inspected both passports, then passed them to her senior colleague, Holly glanced quizzically at Kirsty, who shrugged.

‘Is there something wrong?’ Kirsty asked.

‘We’re looking for an Irishman, David Marlowe,’ the senior officer said, a bamboo lathi in one hand. ‘He was seen embarking this train in Delhi with two female foreign tourists. Have you seen anyone of this name?’

Kirsty glanced at Holly.

‘Yes, he’s travelling in economy,’ Holly said. ‘We only met him on the platform at Nizamuddin. Bit of a loser.’

Kirsty threw her a reproachful, confused look. She knew she should have stayed in Delhi with Anya.

‘Which place was he heading?’ the policewoman asked, making notes on a small pad.

‘Why don’t you ask her,’ Holly said. ‘She knew him better.’

‘He helped us out in a difficult situation on the platform in Delhi,’ Kirsty said, addressing Holly as much as the policewoman. ‘I think he said he was going as far as Vasai.’

Whatever David might have done wrong, Kirsty thought, he had still gone out of his way to help them in Delhi. Holly seemed to have forgotten that.

‘Vasai? He wasn’t travelling to Goa then?’

‘He didn’t have enough money.’

‘Did he say anything else?’

‘No.’

‘And he was travelling alone?’

‘I guess so.’

‘Any luggage?’

‘I don’t think so. Why are you asking me so many questions?’

‘Can you recall what was he wearing?’

‘I don’t know.’ Kirsty suddenly felt very tired. ‘Jeans?’

‘He smelt, that’s all I remember,’ Holly said. Kirsty didn’t even bother to look at her this time. She just wanted to go back to sleep, and wake up in her own bed in Britain.

‘A word of advice, madam,’ the policewoman said, handing back both passports to Kirsty. ‘Stay away from ne’er-do-wells like David Marlowe.’

‘What’s he done?’ Holly asked.

‘You’ll read about it soon enough in today’s papers. He’s dangerous, a slippery fellow.’

36

Fielding had ordered his driver to turn round and head back to the office after dropping Myers in Trafalgar Square, where he said he would pick up a night bus to a friend’s flat in North London. Legoland was reassuringly busy as Fielding took the lift up to his office. It troubled him when the place was quiet. He left a message on Denton’s mobile, asking him to get in early the next day, and then settled back down at his desk to read through Leila’s Developed Vetting report, which he had called up from the night duty manager. At about 3 a.m. he asked for the latest files on the Bahá’í community in Iran, Ali Mousavi, and the London Marathon attack, which needed to be delivered by trolley.

By the time dawn broke, a vivid orange warming the dark Thames beneath his window, Fielding had a better understanding of the threat posed by Leila, and the implications of her unprecedented triple-agent status for the Service, for Stephen Marchant, and for his own career. The Americans would have to make their own assessment, based on a briefing he would give Straker in a few hours. She was their problem now.

The implications for MI6 were still catastrophic, though, if Leila, one of the Service’s star recruits, had been working for VEVAK, Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security, from the day she arrived at Legoland. Developed Vetting, introduced ten years before, was meant to guarantee the highest level of clearance, far superior to routine counter-terrorism and security checks. Such vetting was more important than ever now that the intelligence services were recruiting from such diverse ethnic backgrounds, but in Leila’s case it appeared to have suffered an unprecedented failure.

A wide-ranging interview had been carried out with Leila shortly after she first applied to the Service, followed by two further interviews before she began training at the Fort, nine months after her initial application. The last of these had been conducted in the presence of a senior vetting officer, and triggered an ‘aftercare’ concern about family ties to Iran.