Полная версия

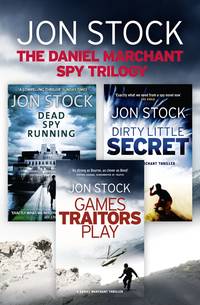

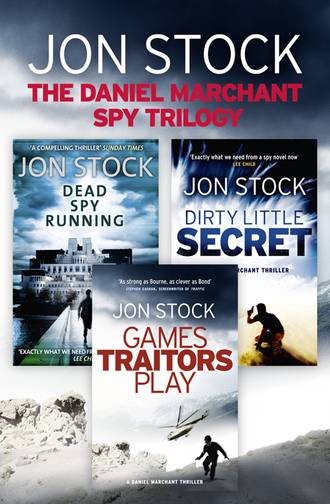

The Daniel Marchant Spy Trilogy: Dead Spy Running, Games Traitors Play, Dirty Little Secret

‘Who is this?’ she asked. His voice sounded familiar.

‘A friend of the family,’ the man said. She could hear other male voices in the background. ‘She’s fine and, inshallah, will have the best treatment dollars can buy.’ The mocking tone was thinly disguised, his words addressed to the others in the room with him.

‘I want her looked after, that was always the deal,’ Leila said, trying not to raise her voice. A man outside the telephone booth glanced up at her. She knew she should be at her mother’s bedside, but that was impossible.

‘I will tell her you called,’ the voice said, then paused. ‘And that her health rests in your hands.’

The sun was at its highest as she walked back towards the embassy. In the distance, an unseen nutseller was rattling his spoon rhythmically against a frying pan. Otherwise there was a stillness in the midday air. Even the traffic police at the junction near the embassy had retreated to the shade, where they snoozed on flimsy wooden chairs. She had never minded dry heat. It somehow made her feel closer to her mother, who she knew needed her now more than ever.

She had just turned nine when she first sensed that all was not well between her parents. They were living in the expat community in Dubai, where her father was working, and he had come home late, as he often did. But this time she was awake. There had been a problem with the electricity in their apartment block–there was not enough power to run the air conditioning, and the sudden warmth had woken her. One of the staff had placed an old fan in the room and she lay there mesmerised by the way it turned as far as it could one way, before sweeping back in the other direction. But above its hum she gradually became aware of shouting downstairs, and then screaming, followed by slammed doors and silence.

She had found her mother curled up in a corner of the kitchen, their Indian maid holding a bloodied cloth to her forehead. Her mother smiled weakly when she saw Leila, but the maid gestured crossly for her to go back upstairs.

‘It’s OK,’ her mother had said, beckoning Leila towards her. She walked tentatively across the kitchen and sat down beside her mother, watched anxiously by the maid. ‘It’s OK,’ her mother repeated, putting a shaking arm around Leila as the maid retreated.

They must have stayed like that for most of the night, hunched together on the marble floor in the heat of a Dubai night, the weak yellow lights flickering. Her mother explained how her father was under a lot of stress at work and sometimes drank too much whisky, hoping that it would make him feel better. But it just made him angry, and when he was angry he wasn’t himself, and did silly things.

In the years that followed, Leila and her mother learnt to be out of the way when he was not himself, but Leila knew that he continued to vent his whisky-fuelled fury on his wife. Not even a burqa could disguise the black eyes. Her father’s long hours and frequent trips abroad meant that she had always been closer to her mother than to him, but his violence bonded them further, uniting them in a mixture of shame and solidarity. She had never forgotten that night, the sight of her mother crying, and could never forgive her father, whose light in her life went out.

All she could do now, slumped on the floor of her bare embassy room, was to fulfil her side of the deal and hope that the voices at the end of the phone in Tehran would honour theirs. But before she could think what that deal might bring, the evening stillness was split by a sound that she knew at once was not thunder.

31

Marchant felt the weight of a body lying on top of him, but he didn’t realise it was Uncle K until he tried to move out from under his heavy frame. Other people were stirring on the bar floor all around him. For a moment, in the dark silence, Marchant was back at the marketplace in Mogadishu. But then the moaning started, guttural cries of primitive pain, and he remembered the quicksilver shards dicing the air, the compression, the chilling cacophony of disintegrating glass.

‘Uncle K, are you OK?’ Marchant asked, trying to shut out the sweet smell of cauterised flesh. It was a smell he hated more than any other, one that had never left him. Now, five years later, the same nagging thoughts were suddenly back once again: could he have done more about the man at the bar?

He was kneeling beside Uncle K now, checklisting his own body as he spoke. He put a hand briefly to his face, touching warm blood as he bent over the colonel. The old man’s features were still intact, the plump, putty-faced cheeks and pursed, rosebud mouth, but the angle of his lower body was too jack-knifed for a seventy-year-old.

Marchant looked at the debris all around him, the lights torn from the ceiling, the upturned tables, shredded curtains. He saw a plastic bottle of mineral water on the floor, a few feet away from him. Reaching over, he dribbled some onto the colonel’s dusty lips, spitting grit out of his own mouth. Slowly, the colonel’s lips began to move. Marchant leant closer, cupping one hand behind his head.

‘You must go,’ the colonel whispered. ‘They will try to blame you for this.’

‘Who will?’

But the colonel had lost consciousness again. Marchant put the bottle to his mouth, spilling water over his lips and chin. Blood was seeping now from the corner of his mouth. The colonel opened his eyes, coughing feebly.

‘You must go,’ he urged. ‘Om Beach, near Gokarna. Ask for…’ The next word was lost in the blood and saliva. ‘…brother Salim at the Namaste Café.’

‘Leila, I want you to get down to the club and slip inside the cordon, assuming the Delhi police have put one up. It’s usually a free-for-all at these things. They might do Golden Temples, but crime-scene golden hours? Give me a break.’

A ripple of polite laughter moved around the room as Monk Johnson, head of the Presidential Protective Detail, addressed a room of ten officers, a mix of Secret Service and CIA. Behind him, a large TV screen was showing library footage from NDTV of the Gymkhana Club before the blast. Cameras had yet to reach the scene. Leila had been tempted to head out into the Delhi evening as soon as she heard the explosion, but she had been summoned to the meeting within minutes. The station was already on a state of high alert: in seventy-two hours the new President of the United States would be flying in to Palam military airbase, five miles from Delhi, as part of his four-country tour of South Asia.

‘I’ve just come off the phone to the Director of the Secret Service,’ Johnson continued. ‘He says POTUS is adamant the tour is still on. The best we can do is buy ourselves a little time: the Islamabad leg could be brought forward, but the Indians won’t like it–they’ve insisted all along that they go first. They tested their nukes before Pakistan, and they want to make damn sure they’re the first to shake the new President’s hand.’

‘You’re assuming this is a Pak thing, right?’ asked David Baldwin, head of the CIA’s Delhi station. He was sitting behind Leila.

‘You tell us. It’s got to be an option. The Gymkhana Club is a colonial hangover, full of army brass.’

‘First up is Salim Dhar. General Casey was due to go there tonight, but cancelled.’

‘Thank God,’ Johnson said.

‘Vivek?’ Baldwin said, ignoring Johnson.

‘Dhar’s exact location on the grid is still to be confirmed, sir,’ Vivek Kumar said, ‘but it has all his hallmarks, particularly if Casey was the target.’

Leila had already been introduced to Kumar as a fellow newcomer. One of the Agency’s brightest analysts, he had been flown in from Langley earlier in the week, and knew more than anyone about Salim Dhar. He knew all about Daniel Marchant, too. Marchant, he said, had left Poland and was already somewhere in India.

‘Widespread military collateral, high-profile US target,’ Kumar continued. ‘We can’t rule out Daniel Marchant either. Right now, that whole situation’s a little complicated. He’s just become the subject of an ongoing level-five covert run by Clandestine, Europe.’

‘Tell me about it,’ Baldwin said, glancing at Leila. ‘I’m speaking to Alan Carter in ten.’

‘OK, let’s re-meet in two hours,’ Johnson said. ‘Unless another bomb goes off. What’s wrong with Texas? Why can’t POTUS go there and shake a few hands?’

Marchant didn’t know who he was fleeing from as he picked his way through the wreckage of the bar and climbed out of a large broken window. It went against every instinct to leave Colonel K, but there had been an urgency to his voice that persuaded Marchant to leave.

He stumbled across the lawn, still dazed, glancing back at the wounded building, curtains lolling from its windows like lacerated tongues. No one could blame him. The Gymkhana Club reception would confirm that a respected Indian colonel had signed him in. But Uncle K was an old friend of his father. He was also travelling as David Marlowe, not Daniel Marchant. Uncle K was right. Daniel was on the run, and once his presence at the club had been discovered, his name would be in the frame. If he could be blamed for the marathon, they would try to pin this one on him too. He thought of the look the man at the bar had given him, purposefully catching his eye. Who was he? Who had sent him?

Marchant had walked through an unmanned side gate and was now on a main road, but the traffic was not as noisy as it should have been. He could barely hear a passing goods lorry, its horn eerily muted. It was then that he realised his ears were resonating with a high-pitched tone that didn’t stop when he shook his head. He looked back towards the club building again, black smoke threading up into the Delhi sky. A rickshaw slowed, its driver eyeing him with a mixture of hope and wariness. Marchant slumped into the back seat and asked for Gokarna.

‘Gokarna?’ the driver asked, smiling in the rear mirror as he throttled the tiny two-stroke engine. ‘Too far, sir, even for Shiva. Airport?’

‘Railway station.’

‘Gymkhana, firework problem?’

Marchant nodded, gripping the side bar of the rickshaw to stop his hand shaking. ‘Big problem,’ he said. On the opposite side of the road, a diplomatic car drove past at speed. Marchant turned back to look at the blue number-plate. It was American. For a moment he thought he recognised the female figure in the back of the car.

32

‘Can we assume that Marchant was at the club?’ Fielding asked, off the floor and back sitting upright at the dining-room table.

‘It’s a Wednesday night,’ Denton said, glancing at the flat screen mounted on the wall. It was now relaying Sky images of a burning Gymkhana Club. ‘We’ve spoken to Warsaw. Bridge night was all he had to go on.’

‘Are you saying you knew where Marchant was?’ Alan Carter asked. He had joined them again after stepping outside the Chief’s office to make a couple of calls to Langley. At Fielding’s request, Anne Norman had reluctantly connected him on a secure line.

‘I thought you knew too,’ Fielding replied.

‘We knew he was in India.’

‘He was to make contact with a colonel who used to work in Indian intelligence. Kailash Malhotra, former number two at RAW. He played in a bridge drive at the Gymkhana on Wednesday nights.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Carter said. ‘The DCIA wants Marchant brought in. I’ve just spoken to his office. He’ll be patched through shortly on the secure video link.’

‘I thought you were more interested in Dhar.’

‘We are. But we’ve also got our new President flying into Delhi Saturday.’

‘We must let Marchant find Dhar.’

‘The timing of this bomb couldn’t be worse, Marcus. I’m not going to be able to hold the hawks back if Marchant was at the club. Spiro isn’t completely out of the picture. The Director and him go way back. It’s a Marines thing. After this, Spiro will be telling him to go after Dhar with everything we’ve got. And it’s hard not to agree with him.’

‘Except that you don’t know where Dhar is.’

‘But the colonel did. He could have told us, told you, saved a lot of time, a lot of lives.’ Carter glanced again at the TV screen. Burnt and blistered bodies were being lined up beneath the club’s Lutyens porch.

‘He would never have told us,’ Fielding said. ‘Our relationship with Delhi is better than yours, but Dhar’s an embarrassment to them. RAW tried to recruit him once.’

‘But he was happy to tell Marchant of Dhar’s whereabouts.’

‘We hoped he might be. He was once very close to his father. But we don’t know what he said. Right now, we don’t even know if Marchant and Malhotra are alive.’

Carter paused. ‘It doesn’t look great, does it? Daniel Marchant, suspected of trying to kill the US Ambassador in London, now at the scene of a bomb blast in Delhi, three days before the President arrives there.’

‘Except that you and I both know that Daniel Marchant wasn’t behind either of those incidents.’

‘He just happened to be present at both. I’m losing my nerve here, Marcus. Remind me why Marchant’s on our side?’

‘Because he’s being set up. And if it’s not by you, then someone’s got us both by the balls.’

‘What makes you so certain?’

‘I knew Stephen Marchant. And I know Daniel. If he’s still alive, he’ll make contact with Dhar.’

‘Who’s walking around Delhi blowing up clubs.’

‘This wasn’t Dhar, Alan. Trust me on this one. Whoever planted this bomb was after Marchant.’

There was a knock on the door, and Anne Norman’s head appeared. She looked straight at Fielding, ignoring Carter. ‘Sir, I’ve got Langley on the line. The DCIA’s ready to join you.’

‘Screen two,’ Fielding said. ‘Thank you, Anne.’

‘Mind if I take the lead on this one?’ Carter said as she closed the door.

‘He’s all yours,’ Fielding said. William Straker, Director of the CIA, flickered into life on a screen next to the one that showed a smouldering Gymkhana Club.

Daniel remembered the red-shirted porters from his last visit to India, when he had travelled the length and breadth of the subcontinent by rail. But he had never seen so many of them before, bobbing through the crowded concourse of Nizamuddin station with suitcases on their scarved heads, sweating, sometimes smiling, always shouting, followed by anxious tourists trying to keep up. For once, nobody pestered him. Porters approached and then melted away, clocking that the farangi had no bags. Or was it the blood and soot on his clothes? They probably thought he was a drug addict, one of the many Westerners who end up begging on the streets of India for enough money to fly home.

He had washed as best he could when the rickshaw dropped him off at the entrance to the station, buying some bottled water at a food stand on the main concourse. It had been the right decision to come straight there, rather than try to pick up his rucksack from the guesthouse. His room would have been searched and ransacked by now. Marlowe’s passport and money were strapped safely to his leg. He would buy new clothes when he was safely out of Delhi. His ticket, third-class, to Karwar, near Gokarna, was in his pocket. All he had to do now was find platform 18, where the Mangala Express to Ernakulam would be leaving in half an hour, twelve hours behind schedule, which wasn’t so bad for a seventy-seven-hour journey.

As he made his way across the concourse, stepping over sleeping bodies and broken clay chai cups, he became aware of a commotion ahead of him, alongside a train that seemed to stretch forever in both directions. Two Western backpackers, both of them young women, were being harangued by an Indian businessman. Marchant slipped into the large crowd that had gathered to watch.

‘How dare you come to our country wearing your next-to-nothings and skimpy whatnots, and complain that our men are Eve-teasers,’ the businessman was saying shrilly. The argument appeared to have been running for several minutes.

‘The guy pinched my bloody arse,’ the younger of the two women said. Marchant detected a faint Australian accent, adopted rather than native, as he glanced at her figure. What little clothing she was wearing wouldn’t have looked out of place on a caged go-go dancer. The elder woman was dressed more modestly. Marchant pushed through the crowd, sensing an opportunity. The cover of travelling in a group would be useful. The women were trapped. When the elder of them told the other one that they should go, the crowd pressed together, preventing them from moving. ‘Out of my way, will you?’ the woman said, panic rising in her voice. ‘I need to get on this train. Hey, stop it! Get off me!’

‘Kareeb khade raho,’ the businessman barked as the crowd pressed against the women. ‘Close in, close in. We keep them here until the police arrive. These Western harlots must be taught a lesson.’

‘Kya problem, hai?’ Marchant said as he reached the businessman. ‘Is there a problem?’ He could smell alcohol on his breath.

‘And who are you?’

‘They’re travelling with me,’ Marchant said, glancing at the two women, who were now visibly frightened. Something in his eyes must have told them that he was on their side.

‘So you must be their pimp.’

‘Kind of,’ Marchant said, resisting the temptation to punch him. ‘We’ve just come from filming the new Shah Rukh Khan movie,’ he said, his voice loud enough to be heard by the crowd. Marchant was thinking quickly. While waiting for Uncle K to meet him at the reception of the Gymkhana Club, he had read in the Hindustan Times how the US President had hoped to visit a Bollywood film set while he was in India, but his itinerary was preventing it. Shah Rukh Khan was making a film at the Red Fort in Delhi, a joint production with a Western company. The star had extended a personal invitation to the President to watch the filming while he was in town.

‘Shah Rukh?’ one of the crowd asked excitedly.

‘Sure. We were only extras, though,’ Marchant said.

‘Did you meet him? My God, you met him, didn’t you?’ said another member of crowd. ‘He met Shah Rukh!’

‘Only to say hello to,’ Marchant continued, looking at the businessman, who clearly didn’t believe a word of what he was hearing. But the less educated crowd, as Marchant had hoped, was already beginning to turn.

‘What was he like?’ someone else called out. ‘Did you hear him sing?’

‘No, we didn’t hear him sing. They add the soundtracks later, you know. But we did see him dance.’

‘With Aishwarya? Did you see her dance, too?’

‘Of course. We were in a large fight scene, playing dirty, filthy Westerners of low moral standing. And I apologise for our appearance now. We had no time to change. The sooner we can board this train the better, then we can dispose of these offensive garments.’ Marchant turned towards the two women. ‘Follow me towards the train as soon as the crowd starts to back off,’ he told them quietly.

‘How can you prove this fanciful story?’ the businessman asked, as Marchant put his head down and made for a carriage door. The crowd, as he had calculated, started to part for the Westerners, ignoring the businessman, who found himself being carried away in the tide of people. ‘And why didn’t these two women mention any of this before?’ he called out after them.

Marchant let the two women climb up into the carriage first, then followed them, before turning to wave to the crowd.

‘You’re not fooling anyone,’ the businessman persisted, pushing his way to the edge of the platform. Marchant was aware that the public scene he had created needed to end quickly. The police would arrive soon, questions would be asked, statements taken. Up until now he had avoided using force, hoping to defuse rather than exacerbate the situation. But the businessman had a doggedness about him that troubled Marchant.

‘Drugs only deceive yourself, my friend,’ the businessman said. ‘You don’t fool me.’

‘I know I don’t,’ Marchant said, leaning down towards him, his mouth close to the man’s ear. ‘But what I do know is that if you try to come after us, or talk to the police, or identify us to anyone, I’ll personally break your neck, just like Shah Rukh does in the film.’

33

In another life, a different time, Marcus Fielding and William Straker might have been close. American intelligence officers everywhere had cheered when Straker was appointed Director of the CIA. He was a spy’s spy, a HUMINT man through and through, rising to head the Agency’s Clandestine Service before taking over as its Director. His appointment had softened the blow of the CIA suddenly finding itself answerable to a higher authority, the new Director of National Intelligence. But working for a DNI suited Straker fine. It helped to deflect some of the unwanted publicity.

Not many clandestines made it to the top of a bureaucracy as big as the CIA. Straker was good for the spy’s soul at a time when Congress was questioning the Agency’s very existence. And his Marines background played well with the paramilitaries, too. He was less popular in London. Straker had personally led the drive to remove Stephen Marchant, which, given Fielding’s loyalty to his predecessor, made for a far from special relationship between the two intelligence chiefs.

But Fielding had been suspicious of Straker long before he helped to remove Marchant. He knew that they should have been allies rather than antagonists. Straker couldn’t be more different from the previous Director, a showman who had somehow emerged from the harsh, post-9/11 spotlight as a celebrity clandestine, savouring the international limelight before retirement and memoirs. Straker was different, more like the British. He had always preferred the penumbral. And as such he was a greater threat to the Service, because he played by the same rules.

‘Sirs,’ Straker said, his manner drilled, precise. ‘There’s not a lot of time. One of our top generals was almost killed tonight. I need to know everything we have on the Gymkhana blast. Was Marchant involved?’

Red lights on three small cameras, mounted on a terminal in the centre of the table, glowed discreetly. Carter glanced at Fielding, who nodded and then looked up at the video screen. ‘Sir, as you know, Marchant’s become the subject of a level-five covert. MI6 think he was at the club, but that he wasn’t responsible.’

‘I thought you’d say that. Just like he wasn’t trying to take out Munroe. Marcus?’

‘Will, I know how this must appear, but we’re convinced Marchant’s being set up here.’

‘Not by us he isn’t,’ Straker said.

Fielding read the subtext–Leila hadn’t been used by the Americans to frame Marchant–and ignored it. To look at, Straker reminded Fielding of one of the thickset rugby players his college at Cambridge used to admit, the promise of an impressive performance on the field outweighing any academic shortcomings off it. Only he knew that Straker was the sharpest officer of his generation. Both fluent Arabic-speakers (Straker spoke Russian and Urdu too), their paths had crossed when he and Fielding had talked Gaddafi out of his nuclear ambitions. For a while there had been a healthy intellectual rivalry between the two of them, until Langley claimed all the credit for castrating Gaddafi.

But what bothered Fielding now was the knowledge that the Leila plan would have been personally signed off by Straker, even if it had been Spiro’s operation. A line was supposed to have been drawn after Stephen Marchant’s resignation, but relations between the CIA and MI6 had remained resolutely sour.

‘I’ve got POTUS touching down in Delhi in seventy-two,’ Straker said, ‘and right now I need a very good reason not to bring Marchant in and lean hard on the Indians to take Dhar out.’

‘It would be better to let Marchant find him first,’ Fielding said coolly. He didn’t care for Straker’s bullying impatience.

‘I appreciate that’s an option, Marcus. It’s why I pulled Spiro and put Alan there in charge. But I was hoping Marchant would lead us to Dhar, not try to take out General Casey at the Gymkhana Club.’

‘We think Dhar might be a potential asset,’ Carter said, glancing at Fielding, who was happy for him to take the lead. Since the discovery of the payments to the Dhar family, Fielding had been wondering how to break the bad news to the Americans. Letting one of their own be the messenger seemed as good a solution as any.