Полная версия

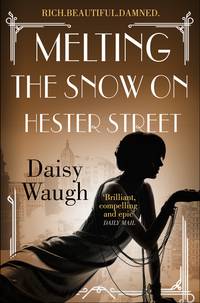

Melting the Snow on Hester Street

They slept sardine-like, side by side on wooden pallets – no room for niceties here; no single-sex wards. On the sixth night, the two of them lay together in the same hot, slumbering room, separated only by a few unwanted bodies, a few feet of space. Neither could have stood it much longer: the proximity and the distance. But Eleana waited, her mind and body restless with longing. She knew he would come to her, and so he did.

Matz clambered over the two sleeping figures between them – Eleana’s young cousin was one, and the other was somebody else. Matz squeezed in beside her. And she regarded him in the semi-darkness. A long time it was they lay like that: a minute or two, or more. And in the beautiful hush, when the noisy world receded, he touched her face – and she touched his, and they saw in each other all that they needed to see, at least for the moment: more than they ever knew it was possible to see in another human being – acceptance, trust, curiosity, desire … Finally, he whispered:

‘You – this moment – no, you, Eleana. This is all I have been able to think of …’

She nodded, curved him a slow, warm smile: ‘I was hoping so,’ she murmured, ‘but my goodness you took your time!’

He laughed – they both did, a whispered laugh – and they made love to each other – they fucked each other – just there and then. Quietly. So quietly. Beside them, the sleeping man – the one who wasn’t the cousin – grunted in his sleep, a half-conscious protest at his small space being disturbed; and shunted up as best he could. But he didn’t wake.

It was a stolen moment: a moment of enchantment and fierce perfection, shared by two people for whom life had only ever offered struggle. It was a moment which amazed them both.

‘Kishefdik!’ Matz whispered. ‘I am a lucky man.’

And she giggled. ‘Kishefdik! Magical. Yes, yes. It was. You are. Let’s do it again.’

He gazed at her, through the tenement gloom. There was a small light shining from the parlour, where a few of them were still at work, attaching mother-of-pearl buttons to a heap of child-sized pantaloons, sixty little buttons an hour, ninety child-sized pantaloons a night, fourteen hours a day. Three dollars more a week. ‘Sheyn maydl, Eleana,’ he whispered, over the hum of the sweatshop sewing machines, the hum which never stopped; over the snores and grunts of his fellow boarders. ‘You’re beautiful … The most beautiful girl I ever saw.’ And she was. He believed she was. Cat’s eyes, green as emeralds, warm as a summer moon; and that soft, smiling mouth, that long slim neck, and those eyes …

‘Your eyes …’ he whispered. ‘All week, all I see are those eyes …’

She didn’t giggle. She looked at him, looking at her, through the tenement gloom. ‘I am not really beautiful,’ she said simply. ‘But you make me feel as though I were.’

That was how it began. And now, three years on, Matz still worked at the Triangle Waist Company factory during the day and, five nights a week, he worked (though it hardly counted as work) at the Hester Street nickelodeon. During the strike, of course, he and Eleana earned nothing from the factory. But thanks to the nickelodeon, they were better off than many. They had moved to another apartment on the same street, no less cramped or dark or crumbling, and even smaller than the last, but without the elevated railway right outside the window, at least, and with fewer roommates. They lived with Eleana’s mother, Batia Kappelman, and Eleana’s pregnant cousin, Sarah Kessler, and Sarah’s brown-eyed baby Tzivia, and (sometimes) with Sarah’s husband Samuel Kessler, who came and went. There was also, temporarily, a greenhorn boarder living with them, a cousin of Sarah’s, fresh from the old country and still finding his feet.

And best of all, of course, there was a daughter, Isha. Two years old – eighteen months older than her cousin Tzivia. The girls were as alike as two peas in a pod, so their grandmother always said. But of course they weren’t. In any case, Matz and Eleana quietly, confidently noted, Isha was not like anyone, not really. She was their golden child. She could walk and talk already, and she had a smile that could melt all the snow on Hester Street, and eyes as wild and green as her mother’s. Her parents wanted nothing less than the world for her: but a different world – one that was kinder and fairer, and which didn’t smell of pickled herring and horse manure and rotting vegetables. And where food was plentiful and the air was clean, and where their baby girl didn’t have to fight for every soot-filled little breath, and wheeze through every airless night, but where she could sleep comfortably, breathe easily, and know that she was safe.

Isha was never strong – not from the first day. But she had bright green eyes, like her mother, and thick dark curly hair, like her father. And laughter that was so easy, so warm, so infectious, it lightened the burden of all and any who were lucky enough to hear it.

So. They were blessed. They had a roof over their heads and enough food on the table – always enough for Isha, and enough, just about, for them. Unlike his fellow strikers, Matz still brought money home from his work at the nickelodeon and there was just enough, after he had given half of it away, to pay the rent. Better than that, in the apartment they shared with only five others, it had been agreed that when the strike was over, and the greenhorn had found his feet, Eleana, Matz and Isha would have a room of their own.

14

Last night, as she had been making her way home from the Greene Street picket line, Eleana had been approached – ambushed, rather – by Mr Blumenkranz, one of the supervisors at Triangle and someone who, when she wasn’t striking, she was forced to deal with on a daily basis. He was a small man, no taller than Eleana, in his late forties, with an unhappy wife at home. Mr Blumenkranz was standing in wait for her, hiding behind a stationary coal cart, because he sensed, quite rightly, that if Eleana had seen him she would have quickly turned and walked the other way. He fell into step as she bustled by, causing her to jump, and offering her no choice but to acknowledge his presence. She glanced about her, unhappy that anyone should spot her fraternizing with the management, and tried to walk on by. But he was quite determined.

‘Eleana!’ he said, panting slightly to keep pace, struggling for a foothold on the ice.

‘Good evening Mr Blumenkranz,’ she replied, cool but polite, not glancing at him, walking faster. Since when, she wondered, had he thought to call her Eleana?

He rarely bothered to learn the machinists’ names – not first names or second names. Most came and went so fast, why would he bother? But there was generally one girl who caught his eye, whose name he always remembered. Eleana was the one. Everybody noticed it. All the girls. And Matz, too. Mr Blumenkranz’s crushes were a long-running joke at Triangle. Sometimes the girl he fixated upon simply left. Couldn’t cope with it. Sometimes, when they wouldn’t submit to his advances, he fired them. Sometimes they accepted his little gifts, his offers of money and stayed for a little while. Until they were fired. Sometimes, rumours circulated about a girl getting herself in trouble. One way or another, nothing good ever seemed to come of his crushes. To their recipients, it was generally deemed, they were less of a blessing than a curse.

But Eleana was clever, in her quiet way. And somehow she had survived Blumenkranz’s cloying attention for longer than the rest, while still keeping him at bay. Her pleasant refusal to engage with him, her ability to slip so innocuously through his fingers, only left him panting for more. Mr Blumenkranz had taken to standing behind her as she bent over her sewing machine, which whirred from the same motor under the same floorboards and at the same speed as the machine beside her, and the machine beside that, and all two hundred machines on the factory’s eighth floor …

‘Ah, Miss Beekman!’ he would sigh, above all the racket of the whirring. ‘A born machinist, if ever there was one!’ As if that were any kind of compliment. And he would turn to the rest of the row, heads bowed, necks and backs twisted over their work: ‘If only all you girls could work as efficiently as the lovely Miss Beekman!’

She corrected him once. ‘It’s Mrs Beekman, Mr Blumenkranz.’ Though, strictly speaking, it wasn’t. She was still Miss Kappelman. She and Matz weren’t yet married. It was something Eleana’s mother protested about from time to time. But somehow they had never quite got around to it. There was always something else more urgent to be done, some other more essential way to spend the time and money.

Mr Blumenkranz knew perfectly well she lived with Matz Beekman the cutter – Union sympathist and nothing but trouble, as far as Blumenkranz was concerned. If he could have his way the man would be fired. But a good cutter was hard to find. And everyone knew, Matz was the best they had. So Blumenkranz ignored Eleana’s comment. He laid a plump, yearning hand on her thin shoulder. ‘Continue your work like this, Miss Beekman,’ he said to her, ‘and before long we shall make you head of the line!’

Head of the line. Meant an extra $1 a week.

‘Head of the line, Miss Beekman! I don’t need to remind you – it’s another dollar a week!’

She let his hand rest on her shoulder – glanced across at Matz briefly, at the far end of the same floor, where the cutters stood. But Matz was oblivious – busy with his knife, slashing away, muttering Marxist revolution into the ear of the cutter beside him. She let Blumenkranz’s finger touch the skin at the top of her neck. Felt nothing – not a shiver of revulsion, because after all, the moment would pass.

When he finally wandered away, Dora, working beside Eleana, glowered at her closest friend.

‘Dershtikt zolstu vern!’ she said furiously. ‘You’re such a fool.’

‘You think so?’ Eleana giggled. ‘Why’s that? The stupid man is driving me crazy!’

‘“Miss” Beekman. “Mrs” Beekman. Who the hell cares? Not you! That’s for sure. Or you might have done something about it.’

‘Oh!’ Eleana tutted mildly. ‘For sure I care.’

‘Blumenkranz adores you, Miss Eleana Kappelman. You’re his One and Only.’

‘Nonsense! Shh!’

Dora chortled. ‘For sure – you’re his Chosen One, Ellie! The Only Girl for Him.’

‘Shut up, Dora!’

‘He loves you better than his own life!’

‘You’ll have us both fired!’

‘Carry on treating him as you do, Eleana, and pretty soon you shall be out of a job. That’s for certain.’

Eleana tipped her head to imply disagreement, but said nothing.

‘You want another a dollar a week? Or don’t you?’ her friend burst out impatiently.

‘Of course I want an extra dollar a week.’

‘Because if you don’t want it, “Mrs” Beekman, I surely do! Mr Blumenkranz can call me anything he likes! I’ll take an extra dollar for it, gladly.’

‘I’m sure you would, my friend,’ Eleana smiled.

‘You think I’m a kurve? Very well. Perhaps it’s so. I am a survivor. That’s what I am.’

‘And a kurve,’ Eleana added, laughing now. ‘And I shall tell your mama, too. The very next time I see her.’

Dora smiled. ‘You think my mama was any better in her day?’

‘Well … yes, Dora.’ Eleana looked at her, quite startled. ‘Indeed I do! And you know it too! You’re mother is a good woman.’

‘Well, Eleana, and so am I. That is exactly my point. I, too, am a good woman. And so are you. But a “good woman” needs to survive. And these are different times. This is America. Life isn’t what it was in the Old—’

‘Oh, please don’t start …’

It wasn’t that Eleana disagreed with her. Far from it. She only wished that all roads, all conversations – everything – didn’t have to lead to the same point. Dora’s socialism was becoming more irksome, more all-consuming than even Matz’s.

Nevertheless, Eleana didn’t correct Mr Blumenkranz again. She put up with his calling her Miss Beekman, leaning over her shoulder so his warm breath ran damp down her spine, and always smiled brightly when he passed. By the time of the strike neither the salary raise, nor the promised head-of-line advancement had materialized. On the other hand, she still had a job at the factory.

And here he was still, all these months later, slip-sliding after her over the ice as she returned from the Greene Street picket line. ‘Wait, Eleana!’ he panted, skidding in the frozen grime. ‘Can’t you stop a moment? I have something terribly important—’

‘I have to get home, sir,’ she said, still walking. ‘I have a small daughter waiting. Unless …’ Away from the factory floor, in these teeming streets, it was harder to hide her disdain. She threw him a glance, mid-stride. ‘Unless of course you have a message for the workers?’ She smiled at him, without warmth. ‘In which case, I’ll be sure to pass it on.’

‘Not for all the workers. No.’

‘Oh. Well then.’

‘Eleana.’ He took hold of her sleeve and pulled her to a halt. She might have snatched it back. She fought the urge. Because – even now, in the street, with the pathetic, pleading look in his eye, he was still powerful. The strike would not last forever, and there was the life beyond it to consider, when Mr Blumenkranz would once again be standing behind her, his hand on her shoulder, his finger on her neck – choosing whether to fire her, or to make her head of the line.

‘What is it, Mr Blumenkranz?’ she snapped.

He seemed surprised, as if he hadn’t really expected her to stop. ‘I have an offer for you,’ he said. ‘I wrote it down …’ He fumbled in the pockets of his thick winter coat. Eleana, standing still and wearing a jacket far thinner than his, began to shiver. ‘Wait a moment,’ he mumbled. ‘Wait there …’ But the paper could not be found, not in all the many pockets of his thick, warm coat and, finally, he abandoned the search. ‘I simply wanted to say … that you’re better than all this! It is irresponsible nonsense, what you are engaged in, and you can do better, Eleana. Much, much better.’

‘Better than what?’

‘Look at you – so cold. Your coat is so thin.’

‘Certainly it is thinner than yours.’

‘Eleana, my dear, you know you cannot win. None of you can win!’

‘Several other factories have already settled. You know they have.’

‘But not Triangle! Mr Blanck and Mr Harris have both said that they will fight you to the end. And they can because they have the rescources, and they have done so and, trust me, they will continue to do so. They will keep the factory working with or without you. They will never accept the Union. Never.’

He looked up at her, spotted the split-second of uncertainty in her eyes and, instinctively, he pressed his advantage. ‘But I could help you,’ he wheedled. ‘If you would allow me, Eleana, I could help you. Did you have breakfast this morning? I’ll bet you didn’t.’ His eyes were on her lips. ‘I can organize a payment. For you. It would be our secret, just between us. I can do that … if you are willing …’

‘What sort of payment, Mr Blumenkranz?’ she asked him politely. ‘Tell me, sir. What did you have in mind?’

But he didn’t hear her, not properly. He was gazing at her lips, and imagining himself, with his arms around her – pushing her back into the alley, right there, behind the rubble, the pile of rotting … whatever it was, and pulling up her skirt – and he couldn’t do all that and listen properly, not at the same time.

‘… Fair pay for all,’ she was saying. ‘Union recognition. Fewer hours for all of us, Mr Blumenkranz, not just for me. It cannot continue …’

‘But I can help you,’ Mr Blumenkranz pleaded. ‘You look hungry. Eleana. Of course you are hungry! What are you living off, while the strike is on? You cannot live on ideals! And nor can your child. Think of your child! Do you need money? I can give you money. How much do you need?’ Again, he was fumbling in his pockets.

But this time, when he looked up, she was gone; vanished. And he was standing alone on the bustling, noisy street. Yearning. Burning.

Such is the lot of the small, plain man with an unhappy wife and a hateful job: neither in one camp nor the other, neither rich nor poor, and in thrall to a young woman who despises him, to whom he has promised a dollar-a-week raise, and from whom, until recently, there had rarely been anything but smiles. No wonder, by the following morning, after he’d tossed and turned and failed to sleep on her rejection, while his unhappy wife snored foully beside him – no wonder he was angry.

15

It had been agreed by strike organizers that the pickets should, as far as possible, consist of young and attractive women workers whose suffering elicited better public sympathy, and that the striking men would be more usefully put to work behind the scenes. So it was that the following morning Eleana was due back on the picket at Greene Street, outside the workers’ entrance to her own factory. Meanwhile, Matz intended to spend the morning flitting between picket lines city-wide, informing strikers of the Union meeting later that day, boosting morale with his eloquent passion and, above all, keeping an eye on the police – who were less liable to erupt into violence when there were men about.

Eleana hadn’t intended to mention the incident with Blumenkranz, but as she and Matz were leaving the apartment that morning – without breakfast, and with a sickly daughter clinging tearfully to Eleana’s neck, the thought flitted through her mind: if she’d said yes to Blumenkranz, how different things would be. There would be breakfast for everyone. And a good breakfast for Isha. There might be a new coat for Isha, too; and warm blankets, a new coat for herself, and even for Matz. She spoke over her daughter’s small, frail shoulder without pausing to think of the consequences:

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.