Полная версия

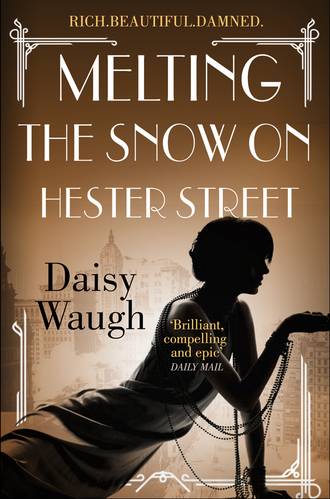

Melting the Snow on Hester Street

‘Hell, Butch – why don’t you sign her!’ Mr Carrascosa called out again. Pleased with the joke. ‘You’re so goddamn fond of her! … She’s costing us an arm and a leg – and for what? She’s finished here, my friend. She’s all yours!’

Butch smiled at them – one of his rare smiles. They had done it to spite him, without doubt. But they would have found another way to spite him if getting rid of Eleanor didn’t also happen to make good business sense. And the numbers were against her: her age, for one; her ticket receipts, for two. And Butch knew – everyone in the business knew – she just wasn’t as good as she used to be. On set, she was professional. She knew what was her best angle and where the kindest light shone; she knew her lines: like an efficient machine, she did everything right. But the tension was gone. She put no heart into it – and somehow, the camera could always pick it up. It’s what Butch had told her, more than once. He’d said it again only a couple of weeks ago.

‘You have to care, Eleanor. You have to care as Max does. As much as I do. As much as you care about life itself …’

‘Of course I care,’ she’d said – beautiful, trained voice crackling with the sound of caring.

It was Butch, then, who’d shaken his head. ‘I can’t protect you from them, Eleanor. You know that. Not if …’ But he couldn’t bring himself to mention it. Two weeks later, he still hadn’t told her he was leaving the studio.

‘I don’t need you to protect me,’ she said. And then, unkindly – she regretted it at once: ‘I have Max to do that.’

But Max had not protected her. Max had gone to Silverman. The truth of it rang out in the silence. Butch, his own guilt hanging heavily, left her statement unchallenged.

‘In any case,’ she added, and kissed him. ‘You mustn’t worry. I’m tougher than I seem.’ And she smiled, and seemed, to Butch, in that instant, to be quite unbearably fragile. He could protect her. If she would only let him.

He kissed her: ‘Eleanor, things might be going to change for me soon. Everything’s going to change. It’s going to be different.’ He stopped. Still, he couldn’t say it. Instead, to fill the silence, he said: ‘I think you should come live with me …’

Eleanor gave him a throaty chuckle: ‘Watch out, Butch Menken,’ she laughed at him. ‘One of these days I may just take you up on the offer …’

They were in his bed, in his new apartment at the Chateau Marmont, an apartment Eleanor had helped him to arrange. It was a beautiful, sultry afternoon. The ceiling fan had kept them cool and, from behind the half-closed louvre shutters, softening the whir of traffic as it chugged down Sunset Boulevard far below, the smallest, sweetest, softest breezes had caressed their warm, naked skin. They were a little drunk, both of them. And she wasn’t listening. She never listened.

10

Butch looked at his watch. Four thirty in the afternoon already. Even taking into account the party last night, to which, of course, he had not been invited, she must have woken and checked her post by now. Why hadn’t she called?

He should call her. He should tell her he was leaving Silverman – if she didn’t know it already. He should talk to her. There was really no way out of it. He knew that. And so, finally, he geared himself to do it. He would call before Max got home and had a chance to break the news to her himself. He would check up on her, make her feel better, soothe her with promises to help …

Grimly, he leaned to pick up the telephone. As he did so his secretary buzzed through on the intercom. Max Beecham was on the line.

HA! It was, Butch realized, the very call he had been waiting not to take all the long afternoon. All day, actually. Ever since his cocktail with Blanche Williams the previous afternoon.

‘Thank you, Mrs Rowse,’ said Butch, soft and succinct as ever. ‘You can tell the son of a bitch I’m out of town.’

‘Out of town. Right you are,’ Mrs Rowse said primly. ‘Shall I say when you’ll be returning?’

‘Tell him I’m back after the weekend. I’m on vacation.’

‘Mr Menken, you’ll be on a reconnaissance out at Palm Springs this coming Monday. Shall I tell him you’ll be back Tuesday?’

‘You tell him that. And tell him you’ve no idea where to find me.’

‘I’ll do that.’

Butch stood up, feeling satisfied. Trying to feel satisfied. The job was done. The son of a bitch could take care of his beautiful wife himself, for once in his lousy, cheating life. Butch had a date with a cute little actress named … Melanie … No, Bethany. From Savannah. Maybe Charleston.

In any case, he was heading home to shower.

11

On those very rare occasions when Max allowed himself to think about it, the truth seemed to shine out like a beacon: the most immutable fact in the universe. Butch Menken had always been in love with his wife. During all the years the three had been working together, Max used to see Butch, watching her, from behind his clever, blue, predatory eyes. And then Max had moved to Silverman. And because she reminded him of so many things he needed to forget, he had turned away from her long before and he had left the two of them together. He never quite knew how long she held out – not quite as long as he might have hoped, perhaps. They were as lonely as each other. But he knew one thing, always. She never stood a chance.

It was all such a long time ago now. But the months and years rolled by – and he knew the affair rumbled on. Or he didn’t know. But he knew. Because Eleanor almost never mentioned Butch’s name, though they worked together; and because Eleanor lied so well, about everything, always, and because she seemed always to be wrapped in an invisible, impenetrable shell. Just as he was.

After his failed attempt to get through to Butch, Max had thrown down his telephone in disgust and immediately, blindly, stormed along the corridor to fight it out with his boss.

Silverman glanced up from his work as Max burst in. ‘Ha!’ he barked cheerfully. ‘Well, I was wondering when you’d finally show your handsome face in here. And before you even start, Max – listen to me. You’re gonna get used to him. Trust me. He’s good news for the studio. Which means he’s good news for you and he’s good news for me.’ And that was it.

When Max tried to present the case against Butch: that he was untrustworthy and extravagant; that his artistic taste was vacuous and shallow; that the sort of big budget films he produced were anathema to all that Silverman Pictures stood for, his employer and friend held up a hand to shush him. And when that didn’t work, and Max continued shouting, he stood up from behind his desk (something he didn’t do often) and simply pushed him from the room.

‘It’ll be good for us,’ was all Joel Silverman would say. ‘Don’t whine, Max. Men should never whine. Butch Menken’s the best producer in the business. He’s just the tonic we need. And if you cared about this studio as much you ought to, you’d be celebrating. Just as I am. Now go home, Max. Lighten up. Enjoy a pleasant weekend with your beautiful wife … And while you’re at it, would you thank her please for a beautiful party last night. Tell her Margaret wants to know where she found those lobster …’

Max returned to the Castillo not long afterwards. Feeling bruised and foolish, and in a filthy mood, he went directly to his study, where he stayed, hidden away, drinking heavily to dull the myriad of pains – among them the ache, ever present, in the palms of his two hands. It was always more acute when he was tired. He sat at his desk and pulled out the old screenplay, the one he turned to whenever his hands burned, or his heart ached, and which one day he swore he would make into a film. After several hours of failing to make any progress with it, he staggered to bed.

All the time he had imagined his wife’s brooding presence somewhere in the house, and was torn between resenting her failure to engage with him, and delighting in not being required to engage with her. But then the bedroom was empty. And then there it was, the miserable little note:

M,

I shall be gone for a few days. I think it’s about time we talked, don’t you?

E

He stared at it stupidly, mind throbbing, trying to work out what in hell it meant. Time to talk? About what? He was tempted to laugh.

Where did she imagine they could possibly begin?

12

New York City, December 1909

Thick snow had settled above the city grime on Hester Street. During the day, the two had mingled under a million tired feet, and this evening the resulting soup had frozen over once again. Eleana’s boots had been restitched so often there was barely anything left to hold them together. They had sucked in the filthy, icy mire, numbed her feet as she stood on Greene Street – and now, in the steaming warmth of the picture house, they were itching and aching as they thawed. It didn’t matter. Not really. It was such a relief to be inside – somewhere warm and cheerful at last – and with Matz at the piano, smiling at her through the crowd. There was neat gin running warm through Eleana’s veins, and hot potato soup in her belly, and the new movie, Frankenstein, playing on a loop on the screen above her head. Her feet could have detached themselves completely and she might not have complained.

Maybe ‘picture house’ was too grand a name for the place. It was a five-cent Lower East Side nickelodeon, a dirty little store front, nothing more, and nothing like the big, fancy theatres opening further uptown. There was a screen at one end, a hand-turned projector at the other, and not enough benches for the boisterous audience between the two. It was packed, as it was every night, even now, with the garment strike – and thick with the smells of tobacco and sweat, and hot, unwashed bodies.

The projection screen was too small, or the film was too large. Something wasn’t right. As always, at the nickelodeon on Hester Street, the top half of the image was bouncing lopsided off the ceiling. But nobody complained. In the normal run of things, such a detail wouldn’t stop the audience from screaming with merry terror: it was Matz Beekman, up to his tricks at the piano keyboard, who was so blithely sabotaging the mood.

Matz was employed five evenings a week (at seventy-five cents a night) to provide musical accompaniment to whatever film was showing. Tonight he had cast aside the official score, as he did from time to time, and was improvising a comic soundtrack of his own – turning what was meant to be a horror show into a ludicrous romp – and the crowd was loving it. Their bellows of laughter could be heard outside on the frozen street, bursting from the room, beckoning more people to join the hot, boisterous crush. Looking at them all, as Eleana did just then, it would have been hard to guess just what and whom they were up against. The garment workers’ general strike, into its third week now, was more widespread – and more successful – than anyone had expected it would be, including the strike organizers. And now the city authorities were turning savage. In cahoots with the factory owners, they were letting their thugs loose on the picket lines, and for the mass of the Lower East Side, garment-manufacturing centre of the world, life had become not merely a struggle to stay warm and to find enough to eat, but a battle – bloody, violent, lawless. To the hunger and the grind, the anonymity and the squalor, there had been added a tang of actual, mortal fear.

Eleana turned her mind from it, from all of it. Everything to do with the strike, and everything connected with it. She concentrated instead on the here and now: the nickelodeon on Hester Street. And Matz at his piano. And Frankenstein and his monster, bouncing off the ceiling.

The film was only sixteen minutes long and Matz knew every frame. He watched movies differently from other people – with the same concentration and passion that he did everything, but with a filmmaker’s instinct, too; though he couldn’t know it yet. It meant he only needed to watch something once, and he could break it down, scene by scene, shot by shot.

No matter what the film was showing, in just a handful of notes, and simply to keep himself amused, Matz could take possession of it, transform the mood. He could send the audience lurching from horror to tears and then to laughter, and carry every soul in the room with him. It was magical. Matz was magical. Eleana loved him most when he was at the piano, hitting the keys, playing the audience – happy and free. He was a different man from the one who stood on stage at the Union halls and called on his fellow workers to strike, or to keep striking, or to keep up the fighting. She loved him then, too – of course. She loved and admired him in the halls. But she loved and desired him at the piano. He would look up suddenly, in the middle of it all, his audience weeping or laughing at his musical command – he would glance up through the crowd, with that look of ferocious concentration, search out Eleana, catch her eye, and his face would break into a wild grin. Often, more and more often, he would beckon her over, forget the film entirely, and instead start hammering out one of the popular songs, in the hope that she might sing along …

Give My Regards to Broadway …, Take Me Out to the Ball Game … , Keep on the Sunny Side …

The crowd never objected. The regulars would holler for her until she came forward to stand beside him.

She didn’t do much. A song and dance. A little routine. The usual schtick. The sort of acts pretty young girls were running through in cheap bars and crowded nickelodeons all over the city. Except, when it came to it, Eleana was anything but usual. Her dark features were too large to be conventionally pretty, and there was a wildness about her, as if she were permanently searching, in hope and fear – and, above all, in vain – for an exit from whatever situation she was in. She was rough hewn, yet: still only a teenager. But she was beautiful. Matz saw it. The crowd saw it, when she sang. In years to come, the camera would see it. She was as magical as Matz up there, standing by that piano: a born performer. Her rich voice, her expressive face, her timing, her intensity, her humour, her lightness of touch – something and everything about her cast a spell. Matz told her so, endlessly. He knew she was a star, all along. He used to say so. And she must have believed it, just a little, or she wouldn’t have continued to stand up there, night after night. She wouldn’t have followed him to the ends of the earth … And she must have heard the applause, felt the warmth. She loved it back then, in the beginning. It made her feel alive.

Tonight, after she sang, they would be passing a hat for the strike fund. And when Matz stopped playing for the evening, when she’d done her song and dance, and the customers were heading home, she might pull him into the cupboard behind that beaten-up piano. Or he might pull her, probably: either way. It was where the proprietor, Mr Listig, stored any reels of film overnight. Not such a big cupboard then: no space to lie down. But big enough. At the end of the evening they always helped to put the reels away, and then – what the hell? Mr Lustig pretended not to notice. He didn’t care (so long as the reels weren’t ruined). Seventy-five cents an evening wasn’t much, after all, and Eleana didn’t even get that. She received nothing, except a wave-through at the door. A little bit of privacy at the end of the night wasn’t much, but it was a luxury not many young couples enjoyed back then, not on the Lower East Side. The use of his cupboard was a perk of the job.

13

She and Matz had been together for three years by then, since Eleana was fifteen. And Matz was eighteen, perhaps. Or seventeen. Nineteen … Matz always travelled light on such details. Until he met Eleana, he seemed to travel entirely alone. He came to America – he said – ten years earlier, alone with his mother, who had died since, to be reunited with his father, who never appeared at the dock to claim him. It was a daily tragedy in New York back then, when so many thousands of immigrants were pouring in every day.

And, to Matz, it was a mystery still. His father had sent the money home, enough for their passage to join him. It had taken him four years to collect enough together: four long, hungry years, saving, scrimping, living no better than a dog in the Lower East slums.

But when wife and son disembarked at last, the Statue of Liberty behind them, and a free life in the New World in front, he wasn’t at the pier to greet them, and though they waited for three days, returned every morning and every afternoon for many more, he never did come. Matz and Matz’s mother never laid eyes on him again.

So that was Matz.

He couldn’t remember his father, anyway. Couldn’t remember his home country, not really. But he remembered this and that: a grandmother, plenty of cousins, and a great crowd – the whole shtetl, his mother said, turning out to wave them off on their journey. He remembered the ship, and the long days at sea: the cramped, stale air on the lower deck, the seasickness – and the lice inspectors at Ellis Island, who had dragged him off, yanked him, screaming, from his mother’s arms. He remembered the wild, overwhelming relief when he was allowed to fall back into her arms again. He would never forget that.

And then … nothing much. The shock of the Lower East Side. The tenement flats, six storeys high, one after the other to the horizon end, blocking the sun, hiding the sky – and the teeming streets, the dirt, the smell of rotting garbage and horse manure, the roar of metal wheels on cobbled roads, the soot that rained from the elevated trains, the endless noise … And his mother finding work, and then working, and working, and never stopping … Someone used to bring vast bundles of materials to the apartment where they boarded, and then she – and the lady who took the rent, and her three daughters and an old man and someone else, and sometimes Matz, too – would sit in silence, too tired to talk, constructing silken flowers for ladies’ hats, by the hundreds, by the thousands, night after night … Someone took the bundles away when the work was completed, and brought back more bundles: a never-ending stream of bundles, squatting in the space, piled high, stealing the daylight …

What he remembers most is that airless August, when she lay dying.

They were boarding with a family on Essex Street, and the family was kind. There was tuberculosis rampant through the block that summer. With so many bodies existing so close together, when the sickness visited a building, as it did from time to time, it took with it whole families, it swept away whole floors of human life. But on this occasion, in Matz’s small apartment, only Matz’s mother fell prey – and the family they boarded with took pity. They let her stay on the only bed, they moved it to the room with the only window, and for those last few weeks, and even for a week or so afterwards, they wouldn’t take any rent from him, and they fed Matz free of charge.

After that – after that – Matz had survived. That was the main thing. He stole food from the carts on Hester Street, collected coal fallen from the back of the coal carts and sold it, or exchanged it, piece by piece. He constructed silk flowers, carried bundles, took work where he could; did whatever he had to do. And in fact he did far better than simply survive. Somehow, between the struggle to earn enough to eat, the struggle to find a place to sleep, Matz achieved what his parents had brought him to the New World to achieve: there was a charitable night school on East Broadway, founded to help little immigrant boys just like him. Without it, who knows what might have happened?

Matz learned English. He learned to read and write. Learned the piano. Discovered Karl Marx. Learned, above all, that life didn’t have to be this way; that it wasn’t this way for everyone.

When he first came to live at Eleana’s tenement flat on Allen Street – his fifth move in a year – he was a member of the Socialist Party of America, and a vocal and active member of the Garment Workers’ Union. He worked ten hours a day as a cutter at the Triangle Waist Company, already one of the largest and most productive garment factories in the city – where, because his job required skill as well as masculine brawn, he earned $12 a week; three times what the young female machinists were paid, working the same hours. He kept only what he needed to survive, and divided the rest between the Party, the Union, and the little boys on the Lower East Side who roamed the streets just as he had, whose fathers never came to meet them at the dock, whose mothers died of consumption by a small window in a filthy street, in a crowded tenement a world away from home.

That was Matz.

By comparison, Eleana had enjoyed an easy life. Who hadn’t? She was born a few crowded streets away, on Orchard Street, five years after her parents arrived off the ship. By the time she was born, her parents were fully Americanized, and took care to speak to Eleana, almost always, in English. Her sister, two years her elder, died of tuberculosis when Eleana was one. Her father, Jethro, shared a lease on a six-by-four feet pickled food store, in the hallway of a neighbouring tenement block. He died of pneumonia, aged thirty-nine, in the winter of 1905, a year or so before she and Matz met. But Eleana often remembered her father: learned, affectionate and kind, always with the smell of pickled herring hanging over him, and – like everyone she knew – always working.

After he died, life grew much tougher. The shop, such that it was, was quickly appropriated by the other lessee, leaving Jethro’s widow and daughter to fend for themselves: Eleana abandoned her education and set to work making up the family income. Easier than Matz’s life, perhaps. But never easy. Before Jethro died, their tiny apartment had been shared only with one uncle and two cousins. Afterwards, innumerable more were crammed in. The apartment, like so many of their neighbours’, became home and sweatshop both, and a flop house for an ever-changing roster of boarders and fellow workers. They sewed buttons onto feathers, or feathers onto ribbons or ribbons onto hats … Whatever piecework was going, they took it in, and sewed – too tired to talk – and sewed – too poorly paid to stop – and sewed, and only paused to sleep.

It was how Matz first encountered her. Old for her years, and with the roster of boarders always passing through, no longer quite the untarnished maiden of good romantic fiction, a toughened daughter of the Lower East Side, but with a bloom that nothing and no one could dim.

There was a heat between them from the moment they met. No doubt about it. She was fifteen. He was eighteen. Maybe. He came back from the Triangle factory that first night. He sat down at the small kitchen table, where the boarders had to eat in shifts. Her mother passed Eleana a plate of schmaltz – chicken fat – and cornbread, which Eleana set before him without a word. He looked up at her – she looked back at him. If it wasn’t love, it was desire at first sight: hot, thick, rich. They gazed at each other, and felt a rush of something wonderful flow through them. They gazed at each other, in no hurry to look away; allowed their eyes to roam each other’s faces as if they were quite alone in the room, as if it were the most natural thing in the world. After a minute, when the current between them seemed to stifle everything else – and there seemed to be no question where it would lead, Eleana’s mother leaned across from the stove and smacked her soup ladle against Matz’s bowl. That was all. She said nothing. Nobody said anything. And, for the instant at least, the spell was partially broken.

There were eight bodies sleeping in that small and crumbling ‘old law’ Allen Street apartment then. Lower East Side was still filled with them – tenements with conditions so foul, with so little light and space, that they were no longer legal. Slowly, they were being replaced. But too slowly. In this small apartment, there lived five family members, loosely connected – not everyone could say quite how – and three boarders, connected only by the fact of the rent. At the end of each day, ten dog-tired bodies returned from their workplaces to be fed by their landlady: pickled herring and cornbread, pickled herring or cornbread, schmaltz, potatoes … mostly potatoes … Eleven bodies squeezed into the four small rooms: a parlour, a windowless kitchen, two windowless bedrooms. Directly outside ran the track for the Second Avenue elevated railroad, which meant a constant thunder and rumble of passing trains, and cinders from the engines floating through the only window, coating the parlour and everything inside it with dust. There was a water faucet in the hallway and a couple of toilets, which serviced all six floors, all seventeen apartments, each one as crammed as the one above, and the one below, and opposite, and on either side …