Полная версия

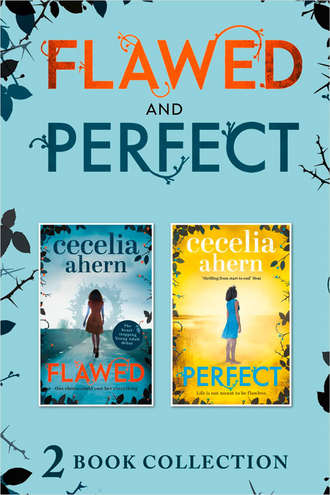

Flawed / Perfect

My mouth drops and I look across at Dad, now understanding why he looks so shattered. Has he spent the whole morning spinning this story?

“But there’s a problem,” Bosco says. “You helped him into a seat. A seat for the flawless. And that is where my colleagues and I cannot agree, and I have spent the past hour discussing it with them. We have failed to mention this part to Pia, but, of course, there were at least a dozen people on that bus who will come forward with the story. They probably even have video.”

He looks at my dad again and my dad nods. He has received a video already, something recorded on someone’s phone on the bus and sent directly into the news station. He’s probably spent the morning fighting for it not to be shown. He knows what will happen if it is.

“Rest assured, your dad will do everything in his power to make sure that video doesn’t hit the airwaves.” It sounds like a threat.

“I told you I’m doing everything that I can,” Dad says, looking him firmly in the eye.

Bosco holds his stare; they look at each other coldly.

Mum clears her throat to snap them out of their stare.

“So,” Bosco says, “after hearing that testimony, I would say this accusation is a grave injustice, as someone who was, in fact, aiding the Guild cannot be condemned to life as a Flawed. However, my fellow judges disagree. With me and with each other. Currently, Judge Jackson, who is normally a sound man, regards your act as a moral misjudgement and would like a Flawed verdict. Judge Sanchez sees your act as aiding and assisting a Flawed, which carries a punishment of imprisonment.”

Mum gasps. I freeze. Dad doesn’t do anything. He probably already knew this.

“As you know, the minimum prison term for aiding a Flawed is eighteen months, and considering this act was carried out so publicly, on public transport, in full sight of thirty people, it carries the highest penalty. We have argued this back and forth.” He sighs, and I hear the weariness, the genuine discontent, at what is happening. “And we have reached an agreement of three years. But you will be released in two years and two months.”

“What?” I say. Two years in prison? But it’s like I’m not there; they’re talking about me like I’m not there.

“It is unfortunate timing for Celestine to have … slipped up,” he says to Mum and Dad. “The vultures out there are willing to make an example of her. Pia can only hold her ground for so long. Cutter, you and your team, of course, are pulling your weight and covering the story as you always should, but there is extreme opposition from the other side. This isn’t so much about Celestine being on trial as the Guild being on trial, and we cannot allow that. We cannot allow that.” He sits up, puffs out his chest. “Cutter, I’ll need your team to step it up. Candy has commented on the fact there has been some recent … upheaval at the station. I think, for the sake of your daughter, the reporting should be in strict keeping with the style and philosophy of the network. No wandering off …”

Is that a threat? Did I just hear Bosco threaten Dad? Candy is Bosco’s sister; she’s in charge of the news network. My head snaps around to look at Dad, and it looks as though there’s another version of him underneath his skin just trying to get out but being contained, restrained with force.

“The pessimists who look backward to some mythical golden age of journalism are mistaken. The golden age is now – and even more so in the immediate future. Candy has quite rightly given Bob Tinder some time off due to personal issues. With the atmosphere as it is now, I need him to be on his toes, performing at a high level to keep the gossip-mongers and the opportunists at bay. The naysayers assume that Celestine will get away with this, that the Flawed court isn’t entirely fair. She is the girlfriend of the son of the judge; she will get special treatment. And that is really what I want to do, Celestine,” he says sadly, genuinely sad. “You make Art happy, the only person who can do that since his mother passed, and I know that he thinks the world of you. But, unfortunately, my colleagues, my own people, also see you as a pawn. They see you as a perfect example to show our doubters how the system is fair. How even the seemingly perfect girlfriend of the son of the head judge can be deemed Flawed. I am fighting two sides, dear Celestine.”

I swallow hard.

“And I agree that no one can be seen to be above the Guild. No one can be seen to escape the justice of the Guild.”

I think of the definition of what the Guild is: it is not a function of the Guild to administer justice; its work is solely inquisitorial. I want to say it aloud, but I know I shouldn’t. Now is not the time for my black-and-white logic, though shouldn’t it be?

“Do you realise just how much trouble you are in, child?” Bosco asks.

“Child,” I say suddenly. “They can’t send me to prison. I’m not eighteen for another six months.”

“Celestine,” he says, “an individual over sixteen can be deemed Flawed, and for a punishment of imprisonment, we can delay the start date until the day of your eighteenth birthday.”

Bosco had said I could have a party on his yacht for my eighteenth birthday. Instead, I could be spending my first night as an adult in prison. I don’t deserve this. Do I? Does anybody? Angelina certainly didn’t.

I look over at the boy in the next room, who is sitting on his bed, with his head down. I wonder how long he has been here; I wonder what he did. Bosco follows my gaze. As if sensing our stares, the boy looks up and looks directly at Bosco with a cold, hard stare, eyes filled with hate. Bosco matches the boy’s look but holds such disgust and contempt for him that I shrivel and almost want to apologise on his behalf.

“You shouldn’t be in here with such scum,” Bosco says simply, and I’m glad the boy can’t hear.

“What did he do?”

“Him? He’s Flawed to the bone,” he says, disgusted. “Though he doesn’t know it yet. I don’t even need to listen to the facts of the case to know his type. I can see it in him. Not like you, Celestine. You are pure. You should not have the future that is destined for him.”

“What do I need to do?” I ask, voice shaking.

“You repeat the story we just discussed, and when they ask you about helping the old man into a seat, you say that you did not, that he sat there himself.”

My mouth falls open. “But the old man will be punished for that.”

“Yes, he will. He’s old and very sick. He’ll probably die before Naming Day anyway.”

The old man did not sit down. He did everything in his strength to stay standing. It was me who helped him to the seat.

“I can’t …”

“You can’t what?” Bosco looks at me.

“I can’t lie.”

“Of course you can’t,” he says, confused, looking at me as if he doesn’t recognise me. “To lie would be to prove that you are Flawed. I would never ask you to lie,” he says, as though insulted. “It is the only way you will go free, prevent being branded for life. It is the only way. What we discussed here now is what happened, and you will confirm that in court, you will say loud and clear for all to hear that society must seek out and oust the Flawed scum in our society. It is the Guild’s work, and you, in full support of the Guild and its values, were working under its rules. You didn’t aid a Flawed. What you did was aid the Guild and, in turn, aid society. That’s what you will tell them. Are we agreed?”

I’m the poster girl. One side wants to use me to prove the Guild is biased; the Guild wants to use me to prove that it isn’t. The perfect girl to prove its power. It wants me to feed the fear.

“Agreed,” I say shakily.

My hearing is this afternoon. The boy in the room beside me, whom I have nicknamed Soldier, has continued to ignore me. I’m sure that seeing me embrace Bosco didn’t do much to sway his initial feelings about me. The word that Pia Wang has been pushing on behalf of Crevan is that I was trying to get rid of the Flawed man from the bus, not help him. If Soldier has seen these reports, which I’m sure he has because Flawed Court TV is the only station we can get on the tiny television in our cells, then that is why he isn’t looking at me. I can only gather from this that he is not anti-Flawed, that he feels my actions were unfair. If only he knew the truth, then he would know he had an ally in the cells. I know this untruth will save my life, but I can’t help but feel embarrassed that this is the perception out there of me. I feel Soldier’s disgust through the wall, and I don’t blame him, but I wonder, if he had the same chance to get out of this, would he take it?

Dad goes back to work and Mum stays with me. She has brought with her a suitcase of my clothes for the trial, and it looks like she went into a clothes store and grabbed every item from the racks. Soldier watches with a sarcastic look as Mum lays out the clothes on my bed, hangs them from every point of the cell she can. He shakes his head and goes back to pacing. I feel self-conscious about all the fuss in my cell when he has been alone all morning, but I try to put his presence out of my mind and concentrate on saving my own life.

“That’s a lot of pink,” I state as I run my eyes over the selection.

“We’ve got pale pink, baby pink, orchid pink, champagne pink, pink lace, cherry blossom pink, lavender pink, cotton candy, hot pink …” Mum lists the shades as she moves along the line, already eliminating the ones she doesn’t like and tossing them back into the suitcase. The hot pinks, candy pinks and lace are removed. The suggestive tops with the low fronts are taken away. We settle on baby pink: skinny cropped trousers and a blouse so light pink it is almost white, buttoned up the centre with ruffles, and a pair of ballet flats. A walk across the cobblestoned courtyard in heels is too much of a stage set for a tripping/heel-getting-caught disaster. Not a good look for the cameras and the hysterical public, who will be there to watch me. The flats are pink and tan leopard print.

“They’re sweet, but they say ‘don’t mess with me’, too,” Mum says. “Remember, in this world, image is everything.”

Tina arrives with a male mannequin, then leaves.

“Sweetheart, this is Mr Berry,” Mum says. “He will be representing your case. Judge Crevan recommended him, says he’s the best. He represented Jimmy Child.”

The mannequin suddenly moves. He offers me a big smile, a smile I don’t believe, a smile that is as fake as the smooth skin on his face. From the neck down he looks sixty; from the chin up he looks thirty. He wears a dapper suit – like he’s just walked out of the airbrushed pages of a magazine – shiny shoes, a handkerchief perfectly positioned in his pocket and gold cuff links to match his gold tie. His face shimmers where his cheekbones have been accentuated, and I definitely see powder on his skin. He’s perfect, and yet I don’t trust him. I look over at Soldier, who is glaring at my newly appointed representative with suspicion. I must say I agree, once again, with his instincts. Our eyes meet, and he shakes his head as though I am nothing and then walks to the far corner of his cell, as far away from me as he can physically get.

“Celestine,” Mum says. She jerks her head in Mr Berry’s direction, and I realise I haven’t acknowledged him yet.

“I’m sorry.” I move forward hastily, as if I’ve been pushed.

“I understand,” he says, devoid of all understanding and affection, through his big white teeth. “So let’s get to it.” He takes his seat and bangs his briefcase down on the table before him. Gold clasps spring open. “Today is just procedure. You won’t be required to say or do anything at all apart from deny the Flawed claim, then they’ll set a time for your trial tomorrow and send you home.”

I breathe a sigh of relief.

“Celestine,” he says, noticing my nerves, “you just stick with me, kiddo, do as I say, and we’ll both be fine. I’ve done this a million times.”

The both is not lost on me.

“Of course, your situation is unique. I don’t usually have every member of the press and MTV outside my door. Not even for Jimmy Child, but then young women in the media are always more interesting. We found that helped us in Jimmy’s case. They were more interested in his wife and her sister than him.”

“MTV?”

“You’re a pretty seventeen-year-old girl from a good part of town, no serious problems, girlfriend of the son of Judge Crevan. What’s not to love about this case? Plus they’re looking for a new reality show, and it looks like you’re their newest target. You represent a generation that will be obsessed with every detail of every aspect of this case, a generation that is pliable, mouldable and just so happens to have more disposable income than any other demographic. Whatever shoes you wear today, they’ll want tomorrow. Whatever earrings you’re wearing, they will sell out by the end of this week. Whatever perfume you wear, there will be a waiting list for it tomorrow. It will be the Celestine North effect. The fashion and sales industry will love you.”

He speaks so fast I can barely keep up with him, and he talks through a smile, which makes it difficult to read his plumped-up lips, which rarely move.

“Every single medium is going to use you for its own motivations – you remember that. You’re a poster girl for the Guild, you’re a poster girl for Anti-Guild, you’re a poster girl for the clothes you’re about to wear and for the lip gloss they’re going to wonder about. Does your daily eating plan include carbs, and how many ab crunches do you do a day? Who styles your hair? How many boyfriends have you had? Have you had a boob job? Should you? Plastic surgeons are lined up and ready to talk about every aspect of you, Celestine North, and I care about all those aspects because they affect the outcome of the biggest question at all: are you Flawed?”

I don’t know if he’s waiting for an answer or not. He is simply studying me, all of me, with his snake-like eyes, which stare at me from under his eyelid-lift, so I don’t respond. I will not give him the benefit, and I wonder again where this stubbornness comes from.

“Everyone is ready and waiting to use you for their own good, just you remember that.”

Everyone? “And what’s your angle?” I ask.

“Celestine.” Mum gasps. “I’m sorry, Mr Berry, but Celestine has the tendency to be so literal about everything.”

“Nothing wrong with that,” Mr Berry says, studying me with his big smile, looking and sounding like there is everything wrong with all of that. “Like I said, today is procedural. You’ll deny the charge, then you’ll go home, and you’ll wait until trial tomorrow. It will all be over by the end of tomorrow. You need to think about character witnesses. Parents, siblings, best friends who’d die for you, that kind of thing.”

“My boyfriend, Art, is my best friend. He’ll speak for me.”

“Sweet,” he says, flicking through his documents, “but he won’t.”

“Why not?” I ask, surprised.

“Better if I ask the questions,” he says. “But seeing as you asked, Judge Crevan has decided he’s off-limits.”

I can tell he’s uncomfortable with this decision, and I understand why. Bosco could not ask his son to lie about my helping the old man to the seat. It makes sense to me, and yet I feel deeply disappointed not to have Art on my side. I need him, and I wonder how hard he fought to speak up for me, or if he fought at all.

“Anyway, it doesn’t matter. Nobody needs to hear how your boyfriend thinks you’re perfect. Every boyfriend either thinks that or will lie about it even if he doesn’t. And he won’t be called as a witness to the scene, because there are thirty other people who are leaping at the chance to do just that. In particular, Margaret and Fiona, the two ladies involved.”

I silently fume, then think hard. “My sister, Juniper.”

“No,” Mum says. “Juniper won’t be taking the stand,” she says to Mr Berry.

They look at each other for a while, speaking a silent language that I don’t understand.

“Why not?” I ask.

“We’ll talk about that later,” she says, smiling, but her eyes are warning me to leave it alone.

So Juniper won’t speak on my behalf. Paranoia tells me she is ashamed of me, she has turned her back on me. She won’t lie for me, or my parents won’t let her lie. They don’t want me to drag her down with me. Why lose two daughters when you can just lose one? My bitterness takes me by surprise. Earlier I hadn’t wanted her to get into trouble, and now when I’m sinking deeper into it, I’m angered by those who are stepping away.

“You have other friends, I assume, and not just your sister and your boyfriend. We only need one.”

Art became my life after his mum passed away, and by spending so much time together, we managed to alienate our group, who, though they understood, also felt a little betrayed and left out. But I know Marlena, my closest friend since childhood, will support me, despite how left out she’s felt lately.

“You’ll be out of here by tonight,” Mr Berry says.

“They won’t keep me here?”

“No, no. They only do that in special cases, for those who are at risk of running, like that young man beside you.”

We all look at Soldier, and Mum visibly shudders. He looks so lost, so angry, he doesn’t stand a chance.

“Who is representing him?”

“Him?” Mr Berry snorts. “He has chosen to represent himself, and he is doing a very bad job. You would almost think he wants to be Flawed.”

“Who would want that?” Mum asks, turning away from him.

I think of the Flawed I pass every day, the people I can’t look in the eye, the people I take steps around to avoid even brushing against. Their scars as identifiers, their armbands, their limited possibilities, living in society but everything they want being just out of reach. You see them all standing at the curfew bus stops in town, to be home by ten pm in winter, eleven pm in summer. In the same world but not living in the same way. Do I want to be like them?

“What’s his name?” I ask.

“I have no idea,” Mr Berry says, bored, wanting to move on.

I look at him alone in there, me here with my selection of clothes, my mum, my representation, the head judge himself. I have people. He must hate me, yet that’s what I must do to get out of here with my life intact. A light goes on for me. I could be in a far worse position. I could be in his situation. All that separates me from him is a lie. I must become imperfect to prove that I am perfect. I have to do everything Mr Berry tells me to do.

Tina brings me a tray of food before I cross the courtyard to the court, but I am too nervous to eat. In the next cell, Soldier gobbles every bite as though his life depends on it.

“What’s his name?” I ask her.

“Him?” She gives him the same look as everyone else has, though she hasn’t treated me like that from the moment I arrived.

“Carrick.”

“Carrick,” I say aloud. Finally, he has a name.

Tina looks at me, eyes narrow and suspicious. “You should stay away from that boy.”

We both watch him, and then I feel the weight of her stare on me as I watch him.

I clear my throat, try to act like I don’t care. “What did he do?”

She looks at him again. “He didn’t need to do anything. Guys like him are just bad eggs.” She looks at my tray. “You’re not eating?”

I shake my head. I’d rather eat when I get home later.

“You’ll be fine, Celestine,” she says gently. “I have a daughter exactly the same age as you. You remind me of her. You shouldn’t be here. You’ll be at home tonight, in your own bed, where you belong.”

I smile at her in thanks.

“They’ve called me upstairs for a meeting.” She makes a face. “First time that’s happened. Wonder what I’ve done wrong.” She makes another face, and then, at my reaction, she laughs. “I’ll be coming back, don’t worry. You’re doing great, kiddo. We’ll go across to the court in thirty minutes, so eat up.”

I can’t touch my food. A new guard, Funar, appears, opens Carrick’s door, and says something to him. Whatever it is, Carrick is eager. He hops up and goes straight to the door. Funar comes to my cell next.

“You want to get some fresh air?”

I jump up. Absolutely. He unlocks my door and I walk behind Carrick, realising, as I see him up close for the first time and not through the glass, how solid and large he is. The muscles in his upper back are expansive, his biceps and triceps permanently flexed. I think about Art and feel guilty for even looking. Funar tries the side door that leads outside, but it’s locked.

“Damn it, I’ll have to go back for the key,” he says. “Sit there and don’t move. I’ll be back in a minute.”

He points to a bench by the wall in a corridor, and we both comply, sitting down side by side.

Our skin isn’t touching, but I can feel the heat from Carrick’s body from where I sit. He’s like a radiator. I’m not sure whether to say anything to him. I don’t even know what to say. He’s not the most approachable person I’ve ever met. Do I ask him about his case? It’s impossible to shoot the breeze in this situation. I sit, frozen, trying to think of something to say, trying to look at him when he’s not looking in my direction. I finally sense he’s about to say something when six people suddenly turn the corner into our corridor. The women are crying and huddling into the men, who are also red-eyed. They walk by us as though they’re in a funeral procession and enter through a door beside us. When it opens, I look in and see a small room with two rows of chairs. It’s facing a floor-to-ceiling pane of glass, which looks into another room. In the centre of the other room sits what looks like an oversized dentist’s chair, and there is a wall of metal units. I see a guard I met earlier named Bark, open one unit, and there is hot fire inside. Confused, I stare in, trying to figure it out.

Then a man, flanked by two guards, is brought down the corridor. He doesn’t look at us. He looks scared, terrified, in fact. He appears to be in his thirties and is wearing what I’d consider a hospital gown, but it’s blood red, the colour of the Flawed. The guards lead him through a separate door from the one the crying women entered, which I’m guessing leads to the room with the dentist’s chair. The Branding Chamber.

Carrick and I both peer in. The door slams in our face. I jump, startled. Carrick sits back, folds his arms and stares ahead intently with a mean look on his face. His look does not invite conversation, so I don’t say anything at all, but I can’t stop fidgeting, wondering what is going on inside that room. After a moment, our silence is broken by the terrifying, bloodcurdling scream of the man inside as his skin is seared by the hot iron bearing the Flawed brand.

I’m stunned at first, but then my body begins to shake. I look across at Carrick, who swallows nervously, his enormous Adam’s apple moving in his thick neck.

Funar strolls up the corridor with a smug look on his face. “Found them,” he sings, jingling the keys in his hand. “They were in my pocket the entire time.” He smiles and unlocks the door, revealing a narrow stairway that leads outside.

Carrick stands up and storms out the door. Once outside, he looks back at me to join him.

Everything around me starts to move. The walls come closer, the floor rises up to meet me. Black spots blot my vision. I feel like I’m going to be sick. Carrick looks at me in concern. I pass out.