Полная версия

You: On a Diet plus Collins GEM Calorie Counter Set

The advent of agriculture essentially started the sociological shift that altered the way we lived—and the way we eat—up until this day. We could now produce food, so we could now produce what we wanted, not necessarily what we needed. Instead of making foods that could both complement our bodies and appeal to our taste buds, we started making ones that were kinder to our tongues and pocketbooks than they were to our waists.

We’re not in the business of trying to make you live like cavemen, or help you score a blue-jeans billboard, or help you become thin enough to escape between two jail bars. What we should acknowledge is that we live in a world with free will, with temptations, and with more eating options than the Mall of America. Biologically, our bodies want us to eat right. But in today’s society (cavemen didn’t have bad bosses or deadlines for annual reports), our biological drive to be the right weight and to eat right can be overcome by stress or temptation. And that has shifted many dietary decisions from biological necessities to psychological reactions. What we’re going to do is teach you how to reprogram your body to work the way it’s supposed to work—so that you eat to satisfy and to fuel rather than to console or excite. Controlling your fat isn’t about being banished with a life sentence of broccoli florets. It’s about teaching your body a little bit about the way our ancestors ate. Naturally and automatically.

YOU TIPS!

Automate Your Eating. If your waist management plan is going to work-as in, really work, for your whole life-then eating right has to become as automatic as it was for our ancestors. That’s not as insurmountable as it seems. Just look at one study from the Journal of the American Medical Association. Two groups were assigned two different diets. One went on a diet rich with good-for-you foods like whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and olive oil, foods found in the typical Mediterranean diet. The other group was not given any specific direction in terms of foods to eat but was instructed to consume specific percentages of fat, carbohydrates, and protein daily. In short, they had to think a lot about preparing foods and dividing amounts, while the first group only had general guidelines about foods to eat.

The groups weren’t given guidelines about how much to eat; they let their hunger levels dictate their hunger patterns. And when they did that, what happened? Without trying, the first group ate fewer calories, lost inches, and dropped pounds.

YOU-reka! The point: The people in the good-foods group ate the foods that naturally kept them satiated so their bodies could seek their playing weights.

The “good-for-YOU-foods group” ate significantly more fiber than the control group (32 grams versus 17 grams).

The “good-for-YOU-foods group” ate higher amounts of good-for-you omega-3 fats in the form of olives, fish, and nuts (especially walnuts). Those fats help increase the level of chemicals that make you feel satiated.

The “good-for-YOU-foods group” more than doubled their consumption of fruits and vegetables.

The “good-for-YOU-foods-group” ate the foods we recommend in the YOU Diet, didn’t obsess about calories, and enabled their bodies to do what they’re supposed to do: regulate the chemicals that are responsible for hunger and for satiety (more on this in Chapter 2).

Don’t Undereat. When our ancestors couldn’t find food and went for long periods of time without it, their bodies acted like a life preserver, storing fat in anticipation of the inevitable periods of famine. The same system works today. YOU-reka! When you try to “diet” by going for long periods of time without eating or by eating way too few calories, your brain senses the starvation and sends an SOS signal through your body to store fat because famine is on its way. That’s why people who go on extreme fasts and extremely low-calorie diets don’t lose the expected weight. They store fat as a natural protective mechanism. To lose weight you have to keep your body from switching into starvation mode. The only way to do it: Eat often, in the form of frequent healthy meals, and snacks.

Plan Your Meals. Start every day knowing when and what you’re going to eat. That way, you’ll avert the 180-degree shift between starving and gorging that occurs when you skip meals. Our fourteen-day diet (in Chapter 12) will show you how to plan your meals so that you feed your body regularly to avoid extreme periods of overeating and undereating that can lead to a gain in weight and inches.

YOU Test

Remember Your Ancestry

Some people say their family has big bones or big cells. Some say their family has big appetites. Some say their family just has big beer coolers. If you gained weight as an adult you can get a relatively accurate picture of what your ideal size should be by thinking about what you looked like when you were eighteen (for women) or twenty-one (for men); a time when you were at your metabolically most efficient and when you weren’t stapled to an office chair for sixty hours a week. Most people gain their weight between the ages of twenty-one and sixty, so by looking at your size at eighteen or twenty-one, you’ll have a good, though not quite scientific, idea of your factory settings. It’s not perfect, but it’s a thumbnail sketch of where you want to be. You can record your waist size (or closest guess) from when you were eighteen, but, more important, think about your shape. Ask your parents about their body sizes-or find pictures of them-when they were eighteen, to help give you a good idea of what you’re supposed to look like.

YOU Test

Stand in Front of the Mirror.

Naked. Without Sucking in Your Belly.

For some of you, this assignment may feel natural, but for most the exercise is as uncomfortable as a coach-class airline seat. We’re having you do this not to benefit the neighborhood peepers, but for two other reasons. First, we want you to realize that we’re emphasizing healthy weight. Not fashion-magazine weight, not featherweight, but healthy weight. And we think that means you have to start getting comfortable with the fact that every woman isn’t as light as a kite, and every man won’t have the body of Matthew McCanoughey. Where you want to be may not be exactly where your body wants you to be. We’re not saying you need to accept a belly that looks like four gallons of melted ice cream, but we want you to get closer to your ideal health-and that means physically and emotionally.

Second, we want you to look at your body. Now draw an outline of your body shape (both from the side and front views). Ask a partner or close friend to look at the shape you drew and tell you-honestly-if that’s approximately what your body looks like. (Your clothes can be back on at this point.) This is just a quality-control check to make sure you have an accurate self body image. (Those with eating disorders have very distorted body images, making it an obstacle for getting back to a healthy weight.) This might be the first time you’ve ever had to articulate things about what your body looks like-and that’s good.

Chapter 2

Can’t Get No Satisfaction

The Science of Appetite

Diet Myths

Hunger is primarily dictated by what’s happening in your stomach.

The biggest battle in dieting involves willpower.

As long as a food is low-fat it’s not going to make you fat.

As much as an iPod bud in the ear, fat has become a regular part of our landscape. We see it everywhere. We see it tethered to a hunk of prime rib. We see it masquerading as a Nutter Butter. We see it crammed into evening gowns or cascading over belt buckles. We’ve seen paparazzi-haunted celebrities gain it and lose it, lose it and gain it. And, if we can bear a confidence-crushing six seconds of nudity in front of a mirror, most of us have seen our own share of flesh that droops, sags, or jiggles. So, reason would tell you that we should know as much about fat as we know about Angelina Jolie’s private life. But we don’t.

Sure, we know what it looks like, what it feels like, and that it can be as bad for our health as a steak knife lodged in our hand. But few of us really know how fat works biologically—how the Twinkie morphs from a wonderfully yellow spongy cake to the flab that conjoins our inner thighs, or how our skinny-as-a-straw friend can wolf down a meat-lover’s supreme while we feel bloated if we as much as sniff four carrots.

Starting in this chapter and continuing throughout the rest of part 2, we’ll show you the way that food travels—from the time your body wants you to eat it, to the time it exercises squatter’s rights on your hips, to the time you fry it into oblivion. The best place to start? With your appetite. Appetite really comes in two forms: physiological signals that make you hungry and emotional coaxes that lure you to food.

In this chapter, we’ll explore those physiological signals, because understanding and controlling your hunger and satiety signals will help you adopt a healthy eating plan. (We’ll explore the psychological and emotional aspects in part 3.) Once you know that those mechanisms have much more powerful control over how you eat than do your taste buds, then you can make the behavioral, attitudinal, and biological adjustments you need to live at your healthy weight.

Above all, there’s one sign that will clue you in to whether you’ve become an effective processor of food. It’s the sign that you, not a bag of gummy bears, are in control of your weight. It’s the sign that you, without having to work at it, have been promoted to captain of your waist management vessel. And it’s the sign that you’ve ultimately reprogrammed your biology so that your body uses food as a medicine to make you stay healthier so that you live long enough to see how Lost ends.

Fat’s Bad Rap

Sure, nobody likes body fat especially when it beats you through the door by five or six seconds. But despite potentially serious consequences, fat, by nature, is good. (That’s not a typo.) Besides helping Santa hopefuls land December jobs, it also helps your cells function and provides insulation. Most of your fat is stored in a reservoir throughout your body. You have drums and drums of it sitting passively, just waiting to be burned. But you have another kind of fat, too. It’s called brown fat and is usually found on the back of your neck and around your arteries (and has absolutely nothing to do with how much chocolate you eat). This increases in outdoor workers during cold spells to protect them from the weather; it insulates our vital organs. Though you have a fairly small percentage of brown fat as an adult about one-third of fat in babies is brown fat and it’s used primarily to keep them warm. What makes brown fat different? YOU-reka! Brown fat is alive. It has nerve fibers, like any organ, and it also has leptin receptors. When the level of this hormone goes up, it turns on energy consumption in the brown fat and burns it. This is important because it shows that the right leptin levels can signal you to immediately get rid of this fat. And it’s also symbolic of the inherent goodness of body fat-when it’s found in the right amounts.

That sign? Satisfaction.

As you change from always thinking about diet to never thinking about it, you will be reprogramming your body so that it’s not your eyes, tongue, or overzealous utensils that will guide you.

YOU-reka! Instead, it will be the chemicals in your brain and body.

By tuning in to your body’s signals, you’ll allow your anatomy to work the way it’s supposed to: so that you’ll never be famished, you’ll never pop a button at the table, and you’ll never bounce between hunger extremes. Instead, you’ll get a little hungry, you’ll eat, you’ll stop. Satisfied.

The Anatomy of Appetite

You’d think that the first place we’d start to talk about how appetite influences fat would be the spot that’s covered by an XXXXL shirt. But to understand appetite, you have to navigate farther north—to the place that may hold the least fat. In your brain, you’ll find the hypothalamus, a key command center for your body. Among the biological functions it controls are your temperature, your metabolism, and your sex drive. Located in the center of your brain, the hypothalamus (see Figure 2.1) also coordinates your behaviors that involve appetite—not just for food but also for thirst and even for sex. So while it may appear that call-to-duty signals come from your stomach growling or your loins tingling like a static shock, it’s actually your brain that’s sending out the signals that you crave either a quiche or a quickie. (At least one person we know helped curb an eating problem by having regular, monogamous, healthy sex. When the appetite function for sex was satisfied, the appetite function for food was diverted.)

FACTOID

As you get older, you have fewer leptin receptors in your hypothalamus-meaning that you have fewer satiety signals, which makes you more prone to gaining weight.

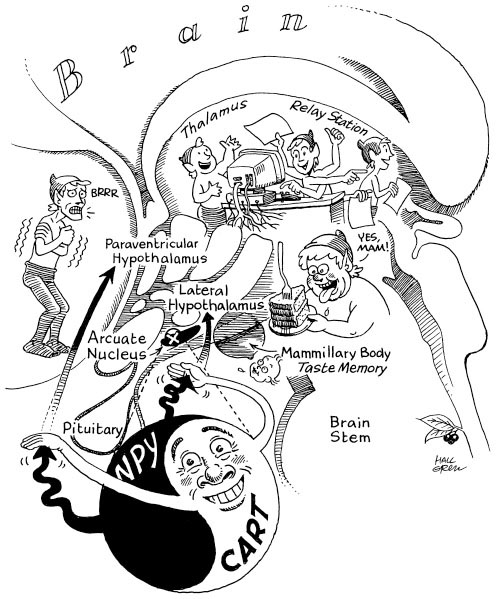

Hidden in your hypothalamus, you have a satiety center that regulates your appetite. It is controlled by two counterbalancing chemicals that are located side by side (see Figure 2.2).

The satiety chemicals led by CART (the C stands for cocaine and the A for amphetamine, since these drugs put this chemical into overdrive). CART stimulates the surrounding hypothalamus to increase metabolism, reduce appetite, and increase insulin to deliver energy to muscle cells rather than be stored as fat.

The eating chemicals driven by NPY (a protein called neuropeptide Y). NPY has the opposite effect on the hypothalamus; it decreases metabolism and increases appetite.

Think of these two command chemicals as any game or sport that involves offense and defense, like soccer, checkers, or even dating. The offense is always trying to make advances, trying to score points, and trying to attack, while the defense protects its territory.

Your eating chemicals play offense. They want as many points as possible, so they fire off those signals for your body to score: eat, eat, eat, calories, calories, calories, chimichanga, chimichanga, chimichanga. The biological message: Prevent starvation by eating. Meanwhile, your satiety chemicals play defense, like a goalkeeper, the back row of checkers, or a protective parent. They send the messages to your brain that you’re full, to shield you from steadily pumping bacon-wrapped scallops down your gullet. How do we know these centers work this way? For one, by looking at extremes and seeing what happens when the feeding system is turned completely on or off. When we study animal models, we see that if a rat’s eating center is destroyed, for instance, it forever forgets to eat. The resulting severe anorexia starves the body of all energy and nutrients so that it withers away to the approximate width of an envelope. In rats whose eating center is overstimulated, though, food is always on the radar screen. And those rats eat themselves to death—literally—by increasing their fat-induced diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and arthritis.

Figure 2.1 Food Fight In your hypothalamus, you have hunger and satiety chemicals. The hormone leptin goes to the satiety center to make you feel full and satisfied, while the signal from the hormone ghrelin makes you want to eat gorge, and slobber over your every feast.

Figure 2.2 Chemical Reaction If we look closely at the hypothalamus, we see that a small nucleus at the bottom houses NPY and CART, which fight the yin-yang battle to control the brain biochemistry of hunger. Each chemical readily travels to other nuclei in the hypothalamus. NPY causes our temperature to drop and our metabolism to decrease as we feel hungry. CART stimulates the opposite influence. The nearby mammillary body (literally shaped like a nipple) is part of our limbic system, where we store memories and emotions—just the right combination to create a craving for a favorite food. The thalamus is the body’s relay station and rapidly transmits orders throughout the brain based on the desires of the eating center.

FACTOID

CART (cocaine-amphetamine-regulatory transcript for those scoring at home) is the reason why cocaine addicts don’t gain weight. Cocaine and amphetamine stimulate this chemical, giving you a double brain bat to help you control appetite and increase metabolism. It’s unclear whether CART will be the basis for effective weight-loss treatments, but researchers are studying the neurological effects these drugs have on appetite to see if they could lead to long-term pharmaceutical solutions to weight loss (without of course, the dangerous side effects of illicit drugs). Marijuana, by the way, has its own receptors that overwhelm leptin, which is one big reason why pot smokers get the munchies. It’s also an area that’s a promising new approach to weight-loss drugs. By figuring out how the drug turns off the gene that produces leptin, we’ll be able to figure out how to flick it on-to keep leptin (and thus satiety levels) high. The prototype drug has done great in trials and symbolizes a new generation of smart weight-loss medications that work hormonally.

In a perfect system, your offense and defense complement each other; you get the foods you need and stop when you’ve had enough. Unfortunately for everyone except elastic-waistband manufacturers, a lot of things can mess up those systems (many of which we’ll discuss in a moment). But these obstacles aren’t insurmountable. You can take comfort (and find motivation) in the fact that your body wants you to reach your goals. Your body doesn’t want to be bigger than it should be. Your body doesn’t want lots of excess fat. Take the case of rats made obese by force-feeding. When they’re allowed to eat freely, they go back to their control weight. They eat what they should eat, without thinking. Same goes for starving rats. When allowed to eat again, they don’t gorge. They naturally go back to their control weight. And we know from years and years of research that what rats do is a pretty fair indication of what humans will do under the same circumstances. (Humans, of course, will do what rats do when they’re motivated only by biology. A rat isn’t upset by stress at home or work, which is why controlling the emotional aspect of eating plays such a big role in effective waist management, as we’ll discuss in Part 3.)

YOU-reka! If you can allow your body and brain to subconsciously do the work of controlling your eating, you’ll naturally gravitate toward your ideal playing weight. You do it by developing a well-trained defense that naturally balances the offense. When you do, you’ll win the diet game every time, whether you have willpower or not. Though it may not always be the case in football or Scrabble, when you pit offense against defense in your body, the offense in your body typically attacks more aggressively. It’s simply easier to scoop up bean dip than it is to leave it for others.

The Hunger On and Off Switches

Duct tape over your mouth isn’t how your body regulates food intake. Your body does it naturally through the communication of substances controlled by your brain. Although there are many hunger- and obesity-related hormones waiting to be discovered, there’s enough evidence to suggest that two hormones have as much influence for dictating our hunger and satiety levels as a head coach does on offense and defense—hour to hour and year to year.

Lovin’ Leptin: The Hormone of Satisfaction

In sumo champions, a little extra fat can produce good results. But we also think that fat has an unfair knock against it. Fat is treated a little like an accused suspect; it sometimes gets a bum rap. Fat produces a chemical signal in your blood that tells you to stop eating. Left to its own devices, fat is self-regulating; the problem occurs when we override our internal monitoring system and continue to stuff ourselves long after we’re no longer hungry. Your body knows when it’s had enough, and it prevents you from wanting any more food on top of that. How does fat curb appetite? Through one of the most important chemicals in the weight-reduction process: leptin, a protein secreted by stored fat. In fact, if leptin is working the way it should, it gives you a double whammy in the fight against fat. The stimulation of leptin (the word comes from the Greek word for “thin”) shuts off your hunger and stimulates you to burn more calories—by stimulating CART.

FACTOID

Neuropeptide Y is a stress hormone that increases with severe or prolonged stress. This may be why some people in chronically stressful situations tend to gain weight. Testosterone, the male sex hormone, seems to stimulate NPY secretion, while the female sex hormone, estrogen, seems to have a varying effect depending on the stage of a woman’s cycle.

But our bodies aren’t always perfect, and leptin doesn’t always work the way it’s supposed to. In some research, when leptin was given to mice, their appetites decreased, as expected. When it was given to people, they initially got thin, but then something strange happened: They overcame the surge of leptin and stopped losing weight. This indicates that our bodies have the ability to override leptin’s message that our tank is full. How? When leptin tells your defense—the satiety chemicals—to kick in and protect you against stray bonbons, the pleasure center in your brain says, “Uh, yeah, three more this-a-way” That surge from the pleasure center, which we’ll discuss in more detail in part 3, can overrule leptin’s messages that you’re full. That’s called leptin resistance (there’s another form of leptin resistance as well, which happens when cells stop accepting leptin’s messages). Most obese people, by the way, have high leptin levels; it’s just that their bodies have the second form of leptin resistance—they don’t receive and respond to leptin signals.

That doesn’t mean leptin is always on the losing end of this chemical battle. YOU-reka! The challenge is to let leptin do its job so that the brain demands less food. One way to do it: Walk thirty minutes a day and build a little muscle (that’s part of our activity plan in part 4). When you lose some weight, your cells become more sensitive and responsive to leptin.

FACTOID