полная версия

полная версияContributions to the Theory of Natural Selection

Having now, I believe, fairly answered the chief objections of the Duke of Argyll, I proceed to notice one or two of those adduced in an able and argumentative essay on the “Origin of Species” in the North British Review for July, 1867. The writer first attempts to prove that there are strict limits to variation. When we begin to select variations in any one direction, the process is comparatively rapid, but after a considerable amount of change has been effected it becomes slower and slower, till at length its limits are reached and no care in breeding and selection can produce any further advance. The race-horse is chosen as an example. It is admitted that, with any ordinary lot of horses to begin with, careful selection would in a few years make a great improvement, and in a comparatively short time the standard of our best racers might be reached. But that standard has not for many years been materially raised, although unlimited wealth and energy are expended in the attempt. This is held to prove that there are definite limits to variation in any special direction, and that we have no reason to suppose that mere time, and the selective process being carried on by natural law, could make any material difference. But the writer does not perceive that this argument fails to meet the real question, which is, not whether indefinite and unlimited change in any or all directions is possible, but whether such differences as do occur in nature could have been produced by the accumulation of variations by selection. In the matter of speed, a limit of a definite kind as regards land animals does exist in nature. All the swiftest animals—deer, antelopes, hares, foxes, lions, leopards, horses, zebras, and many others, have reached very nearly the same degree of speed. Although the swiftest of each must have been for ages preserved, and the slowest must have perished, we have no reason to believe there is any advance of speed. The possible limit under existing conditions, and perhaps under possible terrestrial conditions, has been long ago reached. In cases, however, where this limit had not been so nearly reached as in the horse, we have been enabled to make a more marked advance and to produce a greater difference of form. The wild dog is an animal that hunts much in company, and trusts more to endurance than to speed. Man has produced the greyhound, which differs much more from the wolf or the dingo than the racer does from the wild Arabian. Domestic dogs, again, have varied more in size and in form than the whole family of Canidæ in a state of nature. No wild dog, fox, or wolf, is either so small as some of the smallest terriers and spaniels, or so large as the largest varieties of hound or Newfoundland dog. And, certainly, no two wild animals of the family differ so widely in form and proportions as the Chinese pug and the Italian greyhound, or the bulldog and the common greyhound. The known range of variation is, therefore, more than enough for the derivation of all the forms of Dogs, Wolves, and Foxes from a common ancestor.

Again, it is objected that the Pouter or the Fan-tail pigeon cannot be further developed in the same direction. Variation seems to have reached its limits in these birds. But so it has in nature. The Fan-tail has not only more tail feathers than any of the three hundred and forty existing species of pigeons, but more than any of the eight thousand known species of birds. There is, of course, some limit to the number of feathers of which a tail useful for flight can consist, and in the Fan-tail we have probably reached that limit. Many birds have the œsophagus or the skin of the neck more or less dilatable, but in no known bird is it so dilatable as in the Pouter pigeon. Here again the possible limit, compatible with a healthy existence, has probably been reached. In like manner the differences in the size and form of the beak in the various breeds of the domestic Pigeon, is greater than that between the extreme forms of beak in the various genera and sub-families of the whole Pigeon tribe. From these facts, and many others of the same nature, we may fairly infer, that if rigid selection were applied to any organ, we could in a comparatively short time produce a much greater amount of change than that which occurs between species and species in a state of nature, since the differences which we do produce are often comparable with those which exist between distinct genera or distinct families. The facts adduced by the writer of the article referred to, of the definite limits to variability in certain directions in domesticated animals, are, therefore, no objection whatever to the view, that all the modifications which exist in nature have been produced by the accumulation, by natural selection, of small and useful variations, since those very modifications have equally definite and very similar limits.

Objection to the Argument from Classification

To another of this writer’s objections—that by Professor Thomson’s calculations the sun can only have existed in a solid state 500,000,000 of years, and that therefore time would not suffice for the slow process of development of all living organisms—it is hardly necessary to reply, as it cannot be seriously contended, even if this calculation has claims to approximate accuracy, that the process of change and development may not have been sufficiently rapid to have occurred within that period. His objection to the Classification argument is, however, more plausible. The uncertainty of opinion among Naturalists as to which are species and which varieties, is one of Mr. Darwin’s very strong arguments that these two names cannot belong to things quite distinct in nature and origin. The Reviewer says that this argument is of no weight, because the works of man present exactly the same phenomena; and he instances patent inventions, and the excessive difficulty of determining whether they are new or old. I accept the analogy though it is a very imperfect one, and maintain that such as it is, it is all in favour of Mr. Darwin’s views. For are not all inventions of the same kind directly affiliated to a common ancestor? Are not improved Steam Engines or Clocks the lineal descendants of some existing Steam Engine or Clock? Is there ever a new Creation in Art or Science any more than in Nature? Did ever patentee absolutely originate any complete and entire invention, no portion of which was derived from anything that had been made or described before? It is therefore clear that the difficulty of distinguishing the various classes of inventions which claim to be new, is of the same nature as the difficulty of distinguishing varieties and species, because neither are absolute new creations, but both are alike descendants of pre-existing forms, from which and from each other they differ by varying and often imperceptible degrees. It appears, then, that however plausible this writer’s objections may seem, whenever he descends from generalities to any specific statement, his supposed difficulties turn out to be in reality strongly confirmatory of Mr. Darwin’s view.

The “Times,” on Natural Selection

The extraordinary misconception of the whole subject by popular writers and reviewers, is well shown by an article which appeared in the Times newspaper on “The Reign of Law.” Alluding to the supposed economy of nature, in the adaptation of each species to its own place and its special use, the reviewer remarks: “To this universal law of the greatest economy, the law of natural selection stands in direct antagonism as the law of ‘greatest possible waste’ of time and of creative power. To conceive a duck with webbed feet and a spoon-shaped bill, living by suction, to pass naturally into a gull with webbed feet and a knife-like bill, living on flesh, in the longest possible time and in the most laborious possible way, we may conceive it to pass from the one to the other state by natural selection. The battle of life the ducks will have to fight will increase in peril continually as they cease (with the change of their bill) to be ducks, and attain a maximum of danger in the condition in which they begin to be gulls; and ages must elapse and whole generations must perish, and countless generations of the one species be created and sacrificed, to arrive at one single pair of the other.”

In this passage the theory of natural selection is so absurdly misrepresented that it would be amusing, did we not consider the misleading effect likely to be produced by this kind of teaching in so popular a journal. It is assumed that the duck and the gull are essential parts of nature, each well fitted for its place, and that if one had been produced from the other by a gradual metamorphosis, the intermediate forms would have been useless, unmeaning, and unfitted for any place, in the system of the universe. Now, this idea can only exist in a mind ignorant of the very foundation and essence of the theory of natural selection, which is, the preservation of useful variations only, or, as has been well expressed, in other words, the “survival of the fittest.” Every intermediate form which could possibly have arisen during the transition from the duck to the gull, so far from having an unusually severe battle to fight for existence, or incurring any “maximum of danger,” would necessarily have been as accurately adjusted to the rest of nature, and as well fitted to maintain and to enjoy its existence, as the duck or the gull actually are. If it were not so, it never could have been produced under the law of natural selection.

Intermediate or generalized Forms of extinct Animals, an indication of Transmutation or Development

The misconception of this writer illustrates another point very frequently overlooked. It is an essential part of Mr. Darwin’s theory, that one existing animal has not been derived from any other existing animal, but that both are the descendants of a common ancestor, which was at once different from either, but, in essential characters, intermediate between them both. The illustration of the duck and the gull is therefore misleading; one of these birds has not been derived from the other, but both from a common ancestor. This is not a mere supposition invented to support the theory of natural selection, but is founded on a variety of indisputable facts. As we go back into past time, and meet with the fossil remains of more and more ancient races of extinct animals, we find that many of them actually are intermediate between distinct groups of existing animals. Professor Owen continually dwells on this fact: he says in his “Palæontology,” p. 284: “A more generalized vertebrate structure is illustrated, in the extinct reptiles, by the affinities to ganoid fishes, shown by Ganocephala, Labyrinthodontia, and Icthyopterygia; by the affinities of the Pterosauria to Birds, and by the approximation of the Dinosauria to Mammals. (These have been recently shown by Professor Huxley to have more affinity to Birds.) It is manifested by the combination of modern crocodilian, chelonian, and lacertian characters in the Cryptodontia and the Dicnyodontia, and by the combined lacertian and crocodilian characters in the Thecodontia and Sauropterygia.” In the same work he tells us that, “the Anoplotherium, in several important characters resembled the embryo Ruminant, but retained throughout life those marks of adhesion to a generalized mammalian type;”—and assures us that he has “never omitted a proper opportunity for impressing the results of observations showing the more generalized structures of extinct as compared with the more specialized forms of recent animals.” Modern palæontologists have discovered hundreds of examples of these more generalized or ancestral types. In the time of Cuvier, the Ruminants and the Pachyderms were looked upon as two of the most distinct orders of animals; but it is now demonstrated that there once existed a variety of genera and species, connecting by almost imperceptible grades such widely different animals as the pig and the camel. Among living quadrupeds we can scarcely find a more isolated group than the genus Equus, comprising the horses, asses, and Zebras; but through many species of Paloplotherium, Hippotherium, and Hipparion, and numbers of extinct forms of Equus found in Europe, India, and America, an almost complete transition is established with the Eocene Anoplothorium and Paleotherium, which are also generalized or ancestral types of the Tapir and Rhinoceros. The recent researches of M. Gaudry in Greece have furnished much new evidence of the same character. In the Miocene beds of Pikermi he has discovered the group of the Simocyonidæ intermediate between bears and wolves; the genus Hyænictis which connects the hyænas with the civets; the Ancylotherium, which is allied both to the extinct mastodon and to the living pangolin or scaly ant-eater; and the Helladotherium, which connects the now isolated giraffe with the deer and antelopes.

Between reptiles and fishes an intermediate type has been found in the Archegosaurus of the Coal formation; while the Labyrinthodon of the Trias combined characters of the Batrachia with those of crocodiles, lizards, and ganoid fishes. Even birds, the most apparently isolated of all living forms, and the most rarely preserved in a fossil state, have been shown to possess undoubted affinities with reptiles; and in the Oolitic Archæopteryx, with its lengthened tail, feathered on each side, we have one of the connecting links from the side of birds; while Professor Huxley has recently shown that the entire order of Dinosaurians have remarkable affinities to birds, and that one of them, the Compsognathus, makes a nearer approach to bird organisation than does Archæopteryx to that of reptiles.

Analogous facts to those occur in other classes of animals, as an example of which we have the authority of a distinguished paleontologist, M. Barande, quoted by Mr. Darwin, for the statement, that although the Palæozoic Invertebrata can certainly be classed under existing groups, yet at this ancient period the groups were not so distinctly separated from each other as they are now; while Mr. Scudder tells us, that some of the fossil insects discovered in the Coal formation of America offer characters intermediate between those of existing orders. Agassiz, again, insists strongly that the more ancient animals resemble the embryonic forms of existing species; but as the embryos of distinct groups are known to resemble each other more than the adult animals (and in fact to be undistinguishable at a very early age), this is the same as saying that the ancient animals are exactly what, on Darwin’s theory, the ancestors of existing animals ought to be; and this, it must be remembered, is the evidence of one of the strongest opponents of the theory of natural selection.

Conclusion

I have thus endeavoured to meet fairly, and to answer plainly, a few of the most common objections to the theory of natural selection, and I have done so in every case by referring to admitted facts and to logical deductions from those facts.

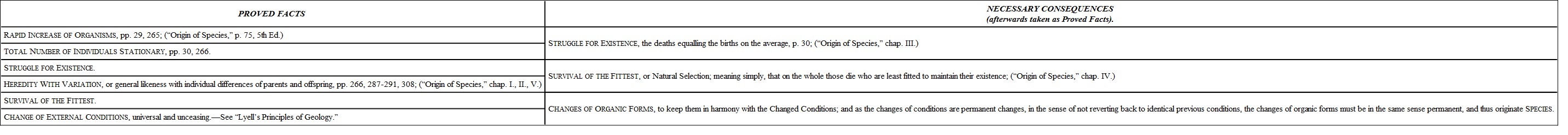

As an indication and general summary of the line of argument I have adopted, I here give a brief demonstration in a tabular form of the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection, referring for the facts to Mr. Darwin’s works, and to the pages in this volume, where they are more or less fully treated.

A Demonstration of the Origin of Species by Natural Selection

IX.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN RACES UNDER THE LAW OF NATURAL SELECTION

Among the most advanced students of man, there exists a wide difference of opinion on some of the most vital questions respecting his nature and origin. Anthropologists are now, indeed, pretty well agreed that man is not a recent introduction into the earth. All who have studied the question, now admit that his antiquity is very great; and that, though we have to some extent ascertained the minimum of time during which he must have existed, we have made no approximation towards determining that far greater period during which he may have, and probably has existed. We can with tolerable certainty affirm that man must have inhabited the earth a thousand centuries ago, but we cannot assert that he positively did not exist, or that there is any good evidence against his having existed, for a period of ten thousand centuries. We know positively, that he was contemporaneous with many now extinct animals, and has survived changes of the earth’s surface fifty or a hundred times greater than any that have occurred during the historical period; but we cannot place any definite limit to the number of species he may have outlived, or to the amount of terrestrial change he may have witnessed.

Wide differences of opinion as to Man’s Origin

But while on this question of man’s antiquity there is a very general agreement,—and all are waiting eagerly for fresh evidence to clear up those points which all admit to be full of doubt,—on other, and not less obscure and difficult questions, a considerable amount of dogmatism is exhibited; doctrines are put forward as established truths, no doubt or hesitation is admitted, and it seems to be supposed that no further evidence is required, or that any new facts can modify our convictions. This is especially the case when we inquire,—Are the various forms under which man now exists primitive, or derived from pre-existing forms; in other words, is man of one or many species? To this question we immediately obtain distinct answers diametrically opposed to each other: the one party positively maintaining, that man is a species and is essentially one—that all differences are but local and temporary variations, produced by the different physical and moral conditions by which he is surrounded; the other party maintaining with equal confidence, that man is a genus of many species, each of which is practically unchangeable, and has ever been as distinct, or even more distinct, than we now behold them. This difference of opinion is somewhat remarkable, when we consider that both parties are well acquainted with the subject; both use the same vast accumulation of facts; both reject those early traditions of mankind which profess to give an account of his origin; and both declare that they are seeking fearlessly after truth alone; yet each will persist in looking only at the portion of truth on his own side of the question, and at the error which is mingled with his opponent’s doctrine. It is my wish to show how the two opposing views can be combined, so as to eliminate the error and retain the truth in each, and it is by means of Mr. Darwin’s celebrated theory of “Natural Selection” that I hope to do this, and thus to harmonise the conflicting theories of modern anthropologists.

Let us first see what each party has to say for itself. In favour of the unity of mankind it is argued, that there are no races without transitions to others; that every race exhibits within itself variations of colour, of hair, of feature, and of form, to such a degree as to bridge over, to a large extent, the gap that separates it from other races. It is asserted that no race is homogeneous; that there is a tendency to vary; that climate, food, and habits produce, and render permanent, physical peculiarities, which, though slight in the limited periods allowed to our observation, would, in the long ages during which the human race has existed, have sufficed to produce all the differences that now appear. It is further asserted that the advocates of the opposite theory do not agree among themselves; that some would make three, some five, some fifty or a hundred and fifty species of man; some would have had each species created in pairs, while others require nations to have at once sprung into existence, and that there is no stability or consistency in any doctrine but that of one primitive stock.

The advocates of the original diversity of man, on the other hand, have much to say for themselves. They argue that proofs of change in man have never been brought forward except to the most trifling amount, while evidence of his permanence meets us everywhere. The Portuguese and Spaniards, settled for two or three centuries in South America, retain their chief physical, mental, and moral characteristics; the Dutch boers at the Cape, and the descendants of the early Dutch settlers in the Moluccas, have not lost the features or the colour of the Germanic races; the Jews, scattered over the world in the most diverse climates, retain the same characteristic lineaments everywhere; the Egyptian sculptures and paintings show us that, for at least 4000 or 5000 years, the strongly contrasted features of the Negro and the Semitic races have remained altogether unchanged; while more recent discoveries prove, that the mound-builders of the Mississippi valley, and the dwellers on Brazilian mountains, had, even in the very infancy of the human race, some traces of the same peculiar and characteristic type of cranial formation that now distinguishes them.

If we endeavour to decide impartially on the merits of this difficult controversy, judging solely by the evidence that each party has brought forward, it certainly seems that the best of the argument is on the side of those who maintain the primitive diversity of man. Their opponents have not been able to refute the permanence of existing races as far back as we can trace them, and have failed to show, in a single case, that at any former epoch the well marked varieties of mankind approximated more closely than they do at the present day. At the same time this is but negative evidence. A condition of immobility for four or five thousand years, does not preclude an advance at an earlier epoch, and—if we can show that there are causes in nature which would check any further physical change when certain conditions were fulfilled—does not even render such an advance improbable, if there are any general arguments to be adduced in its favour. Such a cause, I believe, does exist; and I shall now endeavour to point out its nature and its mode of operation.

Outline of the Theory of Natural Selection

In order to make my argument intelligible, it is necessary for me to explain very briefly the theory of “Natural Selection” promulgated by Mr. Darwin, and the power which it possesses of modifying the forms of animals and plants. The grand feature in the multiplication of organic life is, that close general resemblance is combined with more or less individual variation. The child resembles its parents or ancestors more or less closely in all its peculiarities, deformities, or beauties; it resembles them in general more than it does any other individuals; yet children of the same parents are not all alike, and it often happens that they differ very considerably from their parents and from each other. This is equally true, of man, of all animals, and of all plants. Moreover, it is found that individuals do not differ from their parents in certain particulars only, while in all others they are exact duplicates of them. They differ from them and from each other, in every particular: in form, in size, in colour; in the structure of internal as well as of external organs; in those subtle peculiarities which produce differences of constitution, as well as in those still more subtle ones which lead to modifications of mind and character. In other words, in every possible way, in every organ and in every function, individuals of the same stock vary.

Now, health, strength, and long life, are the results of a harmony between the individual and the universe that surrounds it. Let us suppose that at any given moment this harmony is perfect. A certain animal is exactly fitted to secure its prey, to escape from its enemies, to resist the inclemencies of the seasons, and to rear a numerous and healthy offspring. But a change now takes place. A series of cold winters, for instance, come on, making food scarce, and bringing an immigration of some other animals to compete with the former inhabitants of the district. The new immigrant is swift of foot, and surpasses its rivals in the pursuit of game; the winter nights are colder, and require a thicker fur as a protection, and more nourishing food to keep up the heat of the system. Our supposed perfect animal is no longer in harmony with its universe; it is in danger of dying of cold or of starvation. But the animal varies in its offspring. Some of these are swifter than others—they still manage to catch food enough; some are hardier and more thickly furred—they manage in the cold nights to keep warm enough; the slow, the weak, and the thinly clad soon die off. Again and again, in each succeeding generation, the same thing takes place. By this natural process, which is so inevitable that it cannot be conceived not to act, those best adapted to live, live; those least adapted, die. It is sometimes said that we have no direct evidence of the action of this selecting power in nature. But it seems to me we have better evidence than even direct observation would be, because it is more universal, viz., the evidence of necessity. It must be so; for, as all wild animals increase in a geometrical ratio, while their actual numbers remain on the average stationary, it follows, that as many die annually as are born. If, therefore, we deny natural selection, it can only be by asserting that, in such a case as I have supposed, the strong, the healthy, the swift, the well clad, the well organised animals in every respect, have no advantage over,—do not on the average live longer than, the weak, the unhealthy, the slow, the ill-clad, and the imperfectly organised individuals; and this no sane man has yet been found hardy enough to assert. But this is not all; for the offspring on the average resemble their parents, and the selected portion of each succeeding generation will therefore be stronger, swifter, and more thickly furred than the last; and if this process goes on for thousands of generations, our animal will have again become thoroughly in harmony with the new conditions in which it is placed. But it will now be a different creature. It will be not only swifter and stronger, and more furry, it will also probably have changed in colour, in form, perhaps have acquired a longer tail, or differently shaped ears; for it is an ascertained fact, that when one part of an animal is modified, some other parts almost always change, as it were in sympathy with it. Mr. Darwin calls this “correlation of growth,” and gives as instances, that hairless dogs have imperfect teeth; white cats, when blue-eyed, are deaf; small feet accompany short beaks in pigeons; and other equally interesting cases.