Полная версия

Nature Conservation

Office: 9 Gloucester Road, Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire HR9 5BU.

Plantlife

‘Britain’s only national membership charity dedicated to saving wild plants’ was established in 1989, and now has some 12,000 members and a permanent staff of 18, based in London. Plantlife aims to achieve for plants what the RSPB has done for birds, that is, to improve their lot through a programme of campaigning, practical conservation work and public education. As a small charity with big ideas, it often works in tandem with bodies with similar aims, for example, as a member of the campaign to save peatlands, and has formal links with botanical societies and institutions nationally and internationally. Under its ‘Back from the Brink’ campaign, Plantlife is the ‘lead partner’ for Species Action Plans on a range of rare flowers, bryophytes and fungi. It also runs 22 nature reserves across 17 counties, mainly meadows, heaths and bogs with an outstanding flora. It contributes to plant conservation Europe-wide via the newly founded Planta Europa network, and commissions research reports on matters of current concern, such as bulb theft, controlling the sale of invasive plants (‘At war with aliens’) and managing woods for wild plants (‘Flowers of the forest’). Its magazine, Plantlife, was recently voted the pick of the bunch. Its goal: ‘A world in which the riches of our wild plant inheritance are not diminished by human activity or indifference but are recognised, cherished and enhanced’.

Address: 21 Elizabeth Street, London SW1W 9RP.

Director: Dr Jane Smart.

Plantlife ‘flora guardians’ clearing invasive ‘parrot’s feather’ weed from a plant-rich waterway. (Tim Wilkins/ Plantlife)

Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT)

WWT is ‘the only charity concerned solely with wildfowl and the wetland habitats they rely on’. In 1946, Peter Scott leased 7 hectares of land at Slimbridge, Gloucestershire to establish the Severn Wildfowl Trust, renamed the Wildfowl Trust in 1954. Slimbridge has become home to the most comprehensive collection of ducks, geese and swans in the world. The Trust originally specialised in breeding endangered species, most famously the Nene or Hawaiian Goose, and Slimbridge later became a major research and ‘discovery’ centre. Nine more autonomous ‘Centres’ were established at Peakirk, Walney, Arundel, Martin Mere and Washington in England, Caerlaverock in Scotland, Llanelli in Wales and Castle Espie in Northern Ireland, all but the first being designed as refuges for wild birds (with excellent viewing facilities) rather than as captive breeding centres. The Trust also helped Thames Water to set up the Wetland Centre, on the site of Barn Elms Reservoir in London. It organises wildfowl surveys and advises on conservation worldwide, for example, on the design of a new wetland reserve in Singapore and on reed-bed filtration systems in Hong Kong. It changed its name in 1989 to reflect the Trust’s wider interest in wetland habitats. In 1992, WWT produced a global review on the conservation and management of wildfowl, and played a leading role on the first international conference devoted to these birds. Today it has some 70,000 members, while up to 750,000 people visit its Centres each year. Its newsletter is called The Egg. There is also a biannual research newsletter, Wetland News.

Main Centre: Slimbridge, Gloucestershire GL2 7BT.

The Woodland Trust

Founded by Kenneth Watkins in 1972, the Woodland Trust has been one of the voluntary movement’s surprise successes, striking a chord with our British love of trees and woods. It acquired its first property, Avon Valley Woods in Devon, near Watkins’ home, in 1972, and its 1000th, Coed Maesmelin, near Port Talbot, in 1999. The Trust’s straightforward purpose is to acquire woods of historic, scientific or amenity value, open them to the public and manage them in sympathy with their character. Although still only a medium-sized charity, with 63,000 members, the Trust has a sizeable income – £16.3 million in 1999 – from legacies, landfill tax credits, corporate sponsorship and appeals. It also sells timber on the Internet. It has offices in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and a headquarters at Grantham, Lincolnshire. An admirable proportion of the Trust’s budget goes straight into conservation; for example, in 1999, it spent £5 million on acquiring woods and £6.3 on managing them. Many Trust properties are SSSIs, managed by agreement with one of the conservation agencies, and nearly all of them are de facto nature reserves, with nature conservation a primary aim. Today it owns or manages 1,080 sites covering 17,700 hectares.

With its open house policy, the Woodland Trust aims to promote public enjoyment (‘Wild about Woods’) and to ‘engage local communities in creating, nurturing and enjoying woodland’. It publishes an attractive quarterly newsletter, Broadleaf, and many of its properties have their own leaflets. The Trust also contributes towards the national Millennium Forest project. Though on occasion a little too anxious to plant trees where no trees are needed, the Woodland Trust has saved many fine woods from oblivion, and its overall influence on British woodland management has been benign, and considerable. On ancient woods, its aim is ‘no further losses’.

Address: Autumn Park, Grantham, Lincolnshire NG31 6LL.

Chief Executive: Mike Townsend.

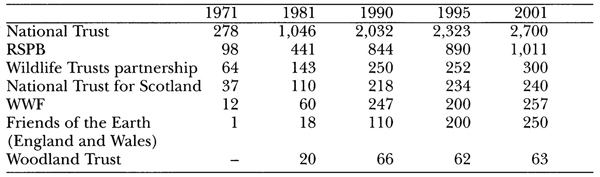

Membership of the large conservation societies (in thousands)

Afterword: my own county trust

The county of Wiltshire has been the domain of great naturalists ever since John Aubrey wrote the first county natural history (Memoires of Naturall Remarques) in 1685. Richard Jefferies lived at Coate, near Swindon, and the location of his Bevis stories is preserved today as a country park. The county boasts one of the classic floras – Donald Grose’s 1957 Flora of Wiltshire. Its lep-idopterists include Baron de Worms, who was in charge of a chemical laboratory at Porton Down, and the Marlborough schoolmaster Edward Meyrick, perhaps the greatest microlepidopterist that ever lived, who lies in my parish churchyard. For 150 years we have had a flourishing Archaeological and Natural History Society based at the county museum, with its own journal. Even the county’s coat of arms commemorates its most characteristic, certainly its most spectacular, species, the now nationally extinct great bustard, standing back to back, in their proper colours.

The Wiltshire Wildlife Trust, then the Wiltshire Trust for Nature Conservation, was formed in 1962. At that time nature conservation was scarcely more than the hobby of a few hundred local naturalists. As one of the founders, Lady Radnor, recalled, ‘We thought then, very innocently, that if we could stop egg-collecting and the men with butterfly-nets, if we could persuade government to ban some of the more deadly pesticides then all would be well’. Agricultural pesticides were the big issue then. A Trowbridge farmer recalled how, walking through the town centre in the early 60s, there was often a lingering niff in the air: not the emissions of some factory but the agricultural sprays from farmers’ fields.

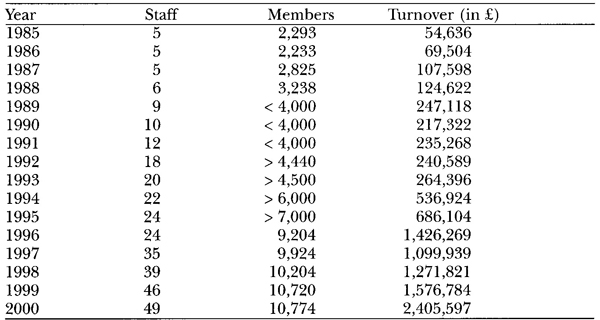

The transformation of the Wiltshire Trust from a modest local charity to a business with over 50 full or part-time staff and an annual turnover of well over a million pounds has taken place quite recently – mostly since 1990. Financially the Trust’s main benefactors have been the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) and the Landfill Tax Credit Scheme, both created in the mid-1990s. Lottery grants have provided many trusts with their biggest windfall, enabling them to buy those long-needed fences or set about restoring wetlands by ambitious damming and drainage schemes. Typically the Fund would provide three-quarters of the costs, leaving the Trust to make up the rest from other donations or its own resources. The Wiltshire Trust was among the first to see the opportunities this presented. As it happened, the HLF’s administrative body, the National Heritage Memorial Fund, was already a good friend of the Trust, having helped it to acquire three nature reserves, including Ravensroost Wood, the Trust’s showcase reserve near Swindon. The opening for business of the Heritage Lottery Fund coincided with the sale of a traditional farm at Jones’s Mill near Pewsey, which the Trust was anxious to save. Its director dashed over to take pictures and filed an application that same day. Two weeks later it had enough money to purchase the important part of the site, which is now a well-loved nature reserve. The HLF has since helped the Trust to purchase sites of national importance, including Clattinger Farm, a ‘time warp’ vista of flower meads untouched by the plough or agricultural chemicals, Coombe Bissett Down, one of the best British sites for burnt-tip orchid, and, most recently, a 235-hectare property at Blakehill Farm for restoration to its former flowery glory. The Wiltshire Trust passes on its experience of working with the Lottery by chairing the Trust partnership’s working group on Lottery funding. Gary Mantle, the Trust’s director since 1990, attributes part of its success in this field in part to the Trust’s relatively modest size: ‘We’re lean and hungry, fleet of foot’. It is also, as I am able to attest (wearing my other hat as a Lottery assessor), impressively businesslike. When it says it will do such and such, it does it. The Lottery appreciates bodies that demonstrate value for money.

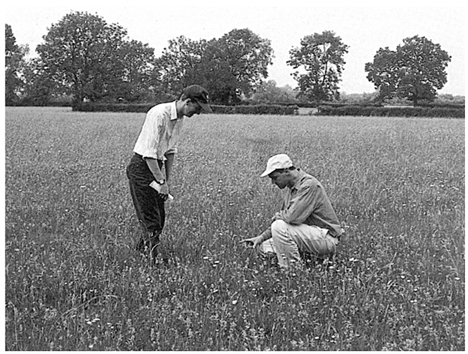

James Power and Gareth Morgan of the Wiltshire Wildlife Trust at Clattinger Farm, which became a Trust reserve in 1997.

Landfill Tax Credit, introduced in the mid-1990s, is the great unsung windfall for voluntary nature conservation. Essentially it is a tax levied on every ton of rubbish buried. Twenty per cent of the tax collected can be retained by the operator and given away to a registered environmental body of its choice. The rules are complicated, but the potential largesse is enormous, with £100 million becoming available for good causes in the first year of operation alone. Wildlife bodies have often been a little slow to spot a potential winner, but the Wiltshire Trust sniffed the air like an emergent vole and pricked up its ears. For several years it had worked with the Hills Group, a large aggregates and landfill operator, on the Braydon Forest countryside management project in the north of the county, in an effort to preserve some glorious countryside close to Swindon and open it to the public. The Trust got itself on the list of eligible charities, and brought along its shopping list of activities. The upshot was that it received a present of £200,000 towards a range of activities. There is, however, a potential conflict of interest between landfill operators and environmental bodies since the latter would really prefer rubbish to be burnt or “recycled rather than buried. A shake-up of how the landfill tax is spent seems imminent.

Like other county trusts, Wiltshire runs a network of nature reserves. Among the 40-odd examples are Blackmoor Copse, famous for its woodland butterflies, which it took over in 1963, and several fine sweeps of downland, including Morgan’s Hill, Great Cheverell Hill and Middleton Down. Two, Ramsbury Meadow and High Clear Down, lie within walking distance of my home. All the Trust’s reserves are run by volunteers; unlike some trusts, Wiltshire has no full-time paid wardens. The Heritage Lottery and other donors have enabled the Trust to specialise in grassland management – an obvious choice since Wiltshire has more chalk downland than any other county, and also a fine series of unimproved neutral grassland meadows. However, the Trust no longer regards nature reserves simply as an end in themselves, but as demonstration sites, and as kernels within a wider area where sustainable and wildlife-friendly land management is the aim. The Wiltshire Trust is ‘farmer friendly’ and many landowners have served it in one way or another. ‘Farmers appreciate a pat on the back,’ says Gary Mantle. ‘It’s nice for them to hear a conservationist say “what a fantastic bit of land”, instead of being criticised all the time, especially when times are hard.’ The trouble nowadays is that managing almost any wildlife habitat has become uneconomic unless it is subsidised in some way, and the kind of stock farmer the trusts rely on most is going out of business.

Most county wildlife trusts contribute to the local planning process by providing details of places of local importance for wildlife which are not quite important enough to be SSSIs. In Wiltshire, these places are called, simply, ‘Wildlife Sites’. They are generally good examples of diminishing habitats, such as coppiced woodland or chalk downs, but also include sites for rare species. Their protection depends on the local authority, generally the district, but in the case of roadsides the county council. ‘Wildlife Sites’ are non-statutory, but in Wiltshire they appear in local plans with a presumption against development. The Trust is given an opportunity to object to unfavourable development, and if necessary defend its stance at a public inquiry. Broadly speaking these places receive about the same level of protection as SSSIs did in the 1970s – perhaps more so, given that local authorities are much more environmentally friendly than they were then.

In other traditional areas of trust activity, the focus has broadened. The county’s local biological records centre, long based at the county museum in Devizes just across the road, is now under the Trust’s wing. This in turn is now part of the National Biodiversity Network, a computerised Wildlife Sites system and public information service. Like all trusts, the Wiltshire one stands up for wildlife at public inquiries, ‘fighting hard to stop the destruction of important wildlife habitats’. But it also joins in the wider struggle to find acceptable policies that would avoid such destruction in the first place, both with ideas and by involving its members and the wider public in local and national campaigns.

Most recently, the Wiltshire Trust has become interested in broader environmental issues. The underlying premise is that it is no longer possible to separate wildlife issues from our own future. The Trust wants to demonstrate that it is doing its bit to promote ideas of energy saving, fair-trading and ‘sustainable gardening’, and practising what it preaches. Behind it lies a conviction that the Trust ought to have the support of at least 100,000 residents in the county, not just its current 10,000 members. To achieve that it needs to come to grips with issues that concern a lot of people, not just those who are keen on natural history. In 1994, the Trust took on the role of managing the county’s local Agenda 21 process. At the time, Mantle went on record as saying he was uncertain whether this would be a complete waste of time or the most important thing they could do – though it would be one or the other. Six years on, having seen the impact of Agenda 21 on tackling issues such as global warming by energy efficiency advice, minimising waste and working for fair trade at home and abroad, he believes they made the right decision. The Trust’s strategy for 2000-2005, headed ‘a sustainable future for wildlife and people’, is upbeat about ‘presenting a positive, hopeful face to the world’: ‘Working to a common purpose we can make a real difference’.

The Trust’s founder, Lady Radnor, recalled a line by Rudyard Kipling: ‘And gardens are not made, By saying Oh how beautiful And sitting in the shade’. Today life seems more complicated than it was back then: ‘the tunnel has grown longer and darker, and taken some very nasty turns’. Wildlife trusts are richer, which enables them to do more, and also to rethink the ground rules about what a local trust is for and what it has to say to the world. Gardens are indeed made by hard work, but they also need creativity and hope, as well as clean rainwater and sustaining soil.

Director: Gary Mantle OBE

Office: Elm Tree Court, Long Street, Devizes, Wiltshire SN10 1NJ.

Growth of a county wildlife trust: Wiltshire Wildlife Trust 1985-2000

4 Conservation Politics: SSSIs and the Law

I have in front of me a thick volume published by the then Department of the Environment and titled Wildlife Crime: A guide to wildlife law enforcement in the UK (Taylor 1996). Its purpose is to try and sort out the legal labyrinth of wildlife law as it stood in 1996, mainly for the benefit of policemen and other law enforcers. More than half of it is devoted to species – birds and their eggs, badgers, deer, seals and salmon, as well as the trade in endangered species. Lists of protected birds in their various grades and schedules take up seven pages, non-avian protected animals and plants another four. On the face of it, Britain’s wildlife looks well protected. But although protection laws may look like nature conservation, much of them are about animal welfare issues. Kindness to animals is an issue for the RSPCA. Conservationists are more concerned with the survival of populations and species than with individuals. However, the legal benefit enjoyed by our wild animals is decidedly mixed. The law has evolved, rather like the landscape, in an ad hoc way, and the result is chock-full of anomalies. Pat Morris (1993) has pointed out that while it is technically illegal to shine a torch at a hedgehog, you can squash one flat with your car without worrying about prosecution. An antique dealer risks a heavy fine for selling an old coat trimmed with pine marten fur, but the law does not help living martens very much. The badger is an exceptionally well-protected animal, but the Ministry of Agriculture slaughters thousands of them. Contrariwise, in the interests of the environment more deer need to be culled, but no one insists on it and so deer continue to multiply. In practice, the government nature conservation agencies spend remarkably little time on species protection. Unlike the US Fish and Wildlife Service, who carry guns and have the power to arrest, Britain’s wildlife agencies have no special powers of enforcement. They devote far more time to managing species under the Biodiversity Action Plan (see Chapter 11), but until 2000 the Plan had no basis in British law. The really important species laws boil down to two: the Wild Birds Protection Act of 1954 and its subsequent amendments, which protect virtually all wild birds, and the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, which protects a lot of other rare animals and plants, mostly from imaginary threats, like collecting, and, more importantly, protects all species of bat, as if they were honorary birds. It is easy enough to protect a species on paper – you simply declare it protected – but quite another thing to bring a successful prosecution. In practice, most prosecutions are to do with birds and bats. Egg collectors, errant gamekeepers and careless timber treatment companies are the principal targets. Animal smugglers are dealt with under international codes enforced under EU regulations.

Protecting a species is pointless unless its habitat is protected too. As the law stood until recently, you could convict someone picking rare orchids in a meadow, but do nothing to prevent a developer or farmer from destroying both the meadow and its orchids. Hence, nature conservation in practice is directed at saving the habitat. Most land in Britain is privately owned and dedicated to some sort of productive use that is usually not nature conservation. In 1949, Government was persuaded by the principle that some portion of the land should be set aside for nature in the interests of at least that part of the population which cares about such things. The principle was not new. The Norman kings set aside land for game for their own selfish purposes. And as Professor Smout reminds us, the eighteenth-century enlightenment took the view that while most of the land is destined for agricultural improvement, some of it should be set aside to delight rather than for productive use – ‘most for man, a little for nature’ (Smout 2000). The contribution of twentieth-century conservationists has been to work out where the best spots for nature lie. The next stage is to see to it that these valuable areas are looked after in a way that ensures they stay valuable.

The Nature Conservancy and its successors evolved methodologies for grading semi-natural land according to its value for wildlife. These were based on attributes such as size (generally the bigger the better), diversity and ‘naturalness’ – based that is, on the quality of the habitat rather than on rare species in isolation. The original idea had been to preserve all the very best examples of woods, heaths, chalk downs and so on as nature reserves. However, that was never going to be enough, so an alternative to direct ownership (or at least proxy management) was needed. From 1949, the Nature Conservancy was allowed to ‘schedule’ any area of land of special interest ‘by reason of its flora and fauna, or geological or physiographical features’. These were (and are) called SSSIs or Sites of Special Scientific Interest. This clumsy term has caused much head-scratching. Here ‘Scientific’ really means ‘nature conservation’ in an adjectival sense. Every now and then someone suggests changing the name, but nothing has ever come of it for fear of adding to the confusion. In any case, until 1981, SSSIs did not amount to very much. The job of the Conservancy was to identify SSSIs, say why they were important and notify them to the local planning authority. In the case of a development requiring planning permission, the local authority would then decide whether to allow the development or refuse it. Of course the local authorities had their own plans and guidelines that were broadly in favour of SSSIs – but ‘the national interest’ always came first, and this could be interpreted in all sorts of ways. Moreover, the most common threats to SSSIs – agricultural improvement or tree planting – did not normally require planning permission. Altogether the Conservancy had been given a very poor hand. It could offer only pennies in compensation, while the ‘improvers’, by way of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Forestry Commission, could offer pounds.

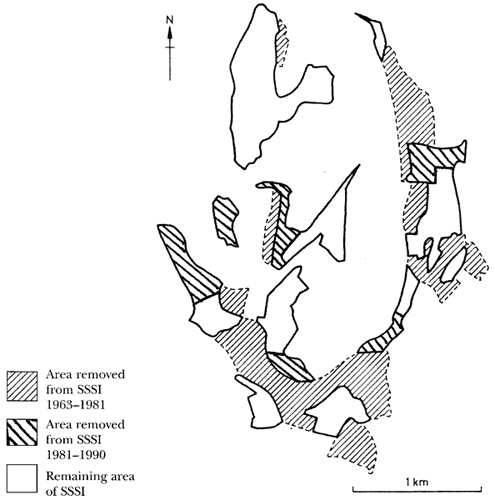

The shrinking of a wildlife site. The Wye and Crundale Downs was recommended by the Wildlife Special Committee as a 1,500-acre (607-hectare) ‘National Reserve’ in 1947 as ‘a first-class example of typical Kentish chalk communities with many characteristic and rare plants and insects’. By 1970 the site had been reduced by ploughing to 415 hectares. Today it measures about 257 hectares (based on W.M. Adams, Nature’s Place).

It is not surprising then, that, before 1981, many SSSIs went under the plough or turned into spruce plantations. For example, in 1963 a farmer received a ploughing grant for the destruction of Waddingham Common SSSI, one of the best natural grassland sites in Lincolnshire. The farmer offered to leave a token acre unploughed. Representatives of the Nature Conservancy and the local wildlife trust insisted on five acres as a bare minimum. The farmer laughed; the entire site was ploughed (Sheail 1998). In Wiltshire, 15 out of 27 chalk grassland SSSIs were ploughed out of existence between 1950 and 1965. In Kent, most of Crundale Downs, proposed in ‘Cmd. 7122’ as a ‘National Reserve’, went the same way (see above). The Nature Conservancy was urged to do more to obtain the co-operation of owners and occupiers through moral persuasion backed by ‘suitable annual payments’. Unfortunately the cash-strapped Conservancy was unable to pay anybody very much, and certainly could not compete with grants for agriculture and forestry.