Полная версия

Nature Conservation

Although the National Trust acquired many places ‘of special interest to the naturalist’ in its early days, such as Wicken Fen, Cheddar Gorge and Box Hill, its management of them was for many years scarcely different to any other rural estate; modern farming and forestry methods that damaged wildlife often went through on the nod. Management of the Trust’s de facto nature reserves, such as Wicken Fen or the tiny Ruskin Reserve near Oxford, was generally overseen by a keen but amateurish outside body. They tended to turn into thickets. The Trust’s outlook began to change in the 1960s after it launched Enterprise Neptune to save the coastline from development, having found that a full third of our coast had been ‘irretrievably spoiled’. By 1995, some 885 kilometres of attractive coast, much of it in south-west England, had been saved in this way.

Since the 1980s, the National Trust has developed in-house ecological expertise, and belatedly become a mainstream conservation body, managing its properties, especially those designated SSSIs, in broad sympathy with wildlife aims. Some of the basic maintenance is done by Trust volunteers in ‘Acorn Workcamps’. Although public access remains a prime aim, some Trust properties are now in effect nature reserves, with the advantage of often being large, especially when integrated with other natural heritage sites. By its centenary year, 1993, the National Trust owned 240,000 hectares of countryside, visited by up to 11 million people every year. It owns large portions of Exmoor, The Lizard and the Lake District, and about 14,000 hectares of ancient woodland and parkland. Like the RSPB, its membership climbed steeply in the 1970s, breaching the million-member tape by 1981. The Trust is now Britain’s largest registered charity, larger than any trades union or any political party. Members receive the annual Trust Handbook of properties, as well as three mailings a year of National Trust Magazine, and free admission to Trust properties (including those belonging to the National Trust for Scotland). It has 16 regional offices in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, as well as a head office in London.

Head Office: 36 Queen Anne’s Gate, London SW1H 9AH [at the time of writing, the National Trust was set to move from its elegant Georgian house in SW1 to a graceless office block in Swindon, to the dismay of most of its staff.]

Director-general: Fiona Reynolds

National Trust for Scotland (NTS)

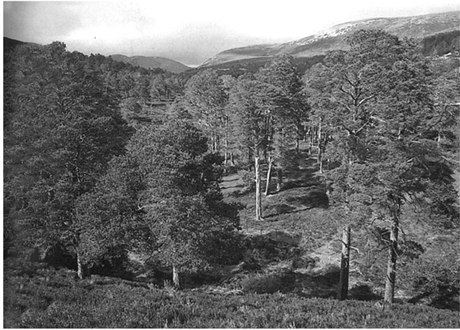

The National Trust’s sister body in Scotland was founded in 1931, and was made a statutory body with similar powers, including inalienability rights, seven years later. It has the same aim of preserving lands and property of historic interest or natural beauty, ‘including the preservation (so far as is practicable) of their natural aspect and features, and animals and plant life’. The Trust acquired its first property, 600 hectares of moorland and cliff on the island of Mull, in 1932. It is now Scotland’s second largest private landowner with nearly 73,000 hectares or about 1 per cent of rural Scotland in its care, including 400 kilometres of coastline. About half of this area consists of designated SSSIs, among them the isles of St Kilda, Fair Isle and Canna, and Highland estates such as Ben Lawers, Ben Lomond, Torridon and Glencoe. Perhaps its most important property is Mar Lodge estate in the Cairngorms, acquired in 1995, which is being managed as a kind of large-scale experiment in woodland regeneration and sustainable land use (pp. 240-41). Like the National Trust, the NTS was for many years more interested in access than habitat management; for example, it had no permanent presence at Ben Lawers until 1972 and, apart from footpath maintenance, did no management to speak of until the 1990s. Though, with 240,000 members, relatively modest in size compared with the National Trust, the NTS is a mainstream and increasingly important partner in nature conservation in Scotland, all the more so since it is an exclusively Scottish body. It has four regional offices with a headquarters – a classic Georgian mansion – in Edinburgh.

Afternoon sunshine sparkles the native pines of Derry Wood in Mar Lodge estate, now owned by the National Trust for Scotland. (Peter Wakely/SNH)

Head Office: 5 Charlotte Square, Edinburgh EH2 4DU.

Chairman: Professor Roger J. Wheater.

International pressure groups

WWF-UK

WWF currently stands for the World Wide Fund for Nature. Until 1986 it was known (more memorably) as the World Wildlife Fund, ‘the world’s largest independent conservation organisation’, with offices in 52 countries and some five million supporters worldwide. WWF was founded by Peter Scott and others in 1961, and is registered as a charity in Switzerland. Its mission: ‘to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment, and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature’. The UK branch, WWF’s first national organisation, has funded over 3,000 conservation projects since 1961 (but especially since 1990), and itself campaigns to save endangered species and improve legal protection for wildlife. In the 1990s it produced a succession of valuable reports on the marine environment, wild salmon, translocations, SSSIs and other topics from a more independent viewpoint than one expects nowadays from government bodies. In a sense, it has taken over as the lead body reporting on the health of Britain’s natural environment and the effectiveness of conservation measures. Among its most important contributions has been WWF’s persistent prodding of the UK government over the EU Habitats Directive, which eventually led to a large increase in proposed SACs (Special Areas for Conservation) for the Natura 2000 network (see Chapter 4). All of WWF’s work is supposed to have a global relevance. WWF-UK’s work is currently organised into three programmes: ‘Living Seas’, ‘Future Landscapes’ (countryside, forest and fresh water) and ‘Business and Consumption’ (‘our lifestyles and their impact on nature’). It also works with others overseas to promote sustainable development in ecologically rich parts of the world and good environmental behaviour by businesses. The organisation is funded mainly by voluntary donations (90 per cent), with the rest from state institutions. The UK branch has some 257,000 members and supporters, and 200 volunteer groups about the country. Its youth section is called ‘Go Wild’. It has offices in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland with a headquarters at Godalming in Surrey.

Its logo: the famous panda, designed by Peter Scott. Its slogan: ‘Taking action for a living planet’.

Address: Panda House, Weyside Park, Godalming, Surrey GU7 1XR. Chief Executive: Robert Napier

Friends of the Earth

FoE acts as a radical environmental ginger group, pressing for more environment-friendly policies, both at home and worldwide. It is careful to avoid alignment with any political party or to accept commercial sponsorship, and most of its funding comes from the membership. FoE is particularly effective at ‘media management’ and at shaming commercial interests into adopting more environmentally friendly policies. Founded in America, a British branch took root shortly afterwards in 1971. Its first newsworthy action was the dumping of thousands of non-returnable bottles on the doorstep of Schweppes, the soft drink manufacturers. On wildlife matters, FoE has taken the lead on major issues, such as the protests over the Newbury bypass, on peat products and GM crops, dumping in the North Sea and pressing for stronger measures to protect SSSIs. FoE are a streetwise organisation with a youngish membership, and its language is characteristically urgent and emotional (‘Our planet faces terrible dangers’, ‘We can’t allow environmental vandals to lay waste the earth’ etc.). By persistently hammering away at an issue in an outraged tone, whilst also seeming well informed, FoE builds up a momentum for change. Its quarter of a million UK members receive a highly professional quarterly magazine, Earth Matters, and plenty of appeals, stickers and campaign literature. Its slogan: ‘for the planet for people’.

Address: 26-28 Underwood Street, London N1 7JQ.

Executive director: Charles Secrett.

Greenpeace

The most headline-making of all respectable environmental organisations was founded in America in 1971. The public first heard about Greenpeace when a group of activists sailed into an atomic testing zone in a battered hire-boat. A UK branch was formed the same year. Greenpeace is an international environment-protection body, funded by individual donations. It specialises in non-violent, direct action: front page pictures of activists being hosed from whaling ships, or waving banners at the top of chimneys, or on derelict oil platforms, alerts public opinion and raises awareness of an issue. Famously, its ship, the Rainbow Warrior, was blown up in Auckland harbour by French agents in 1985. Behind the headlines lie quieter activities: producing reports, lobbying governments, talking to businesses and even conducting research. Greenpeace concentrates on international campaigns, such as nuclear test bans, or the banning of drift nets or mining in the Antarctic. Among recent activities that impinge on nature conservation in Britain are campaigns for renewable energy and against GM crops. It exploits ‘consumer power’ by dissuading companies from using products from ancient forests and peatlands. Greenpeace has 176,000 supporters in the UK and a claimed 2.5 million worldwide. Its slogan: ‘Wanted. One person to change the world’.

Lord Peter Melchett, former chair of Wildlife Link and Executive Director of Greenpeace until 2001. (Greenpeace/Davison)

UK Office: Canonbury Villas, London N1 2PN

Executive director: Peter Melchett (until December 2001)

The link body

Wildlife and Countryside Link (and predecessors)

Wildlife and Countryside Link (originally Wildlife Link) is an umbrella body representing 34 voluntary bodies in the UK with a total of six million members. It is funded by the member organisations, which also take turns to chair its meetings, plus donations from WWF-UK, the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR), English Nature and the Countryside Agency. It functions through various working groups and ‘task forces’, as well as ‘one-off initiatives’ covering a wide range of environmental issues at home and abroad, including rural development, trading in wildlife, land-use planning and the marine environment. Wildlife Link has played an important co-ordinating role in shaping current wildlife protection policies, enabling the voluntary bodies to pool their resources and experience and present a common agenda. It has a small secretariat based in London. In keeping with the spirit of devolution, there are now separate Wildlife and Countryside Links in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The need for an umbrella body to represent the proliferating voluntary societies was appreciated as early as 1958, when the Council for Nature was formed as a voice for some 450 societies and local institutions, ranging from specialist societies to local museums and local field clubs. Headed by the glitterati of the 1960s conservation world, it helped to establish nature conservation in hearts and minds with events like the two National Nature Weeks and the three Countryside in 1970 conferences. It also helped to set up the Conservation Corps, later to become the BTCV (p. 70), while the Council’s Youth Committee, under Bruce Campbell, did its best to ‘make people of all ages conscious of their responsibility for the natural environment’ (Stamp 1969). Its publications were a monthly broadsheet, Habitat, and a twice-yearly News for Naturalists.

Despite its influence, the Council for Nature was always short of money. By the mid-1970s, it was ailing badly, and four years later had ceased to function. Its publication Habitat was continued by the Council for Environmental Conservation (CoEnCo, now the Environment Council) while its function as an umbrella body was taken on by the newly founded Wildlife Link, then a committee of CoEnCo under Lord (Peter) Melchett. Wildlife Link scored an early success with the Wildlife and Countryside Act (see next chapter). In 1993 the name was changed to Wildlife and Countryside Link to emphasise its wider remit.

Secretariat: 89 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7TP.

Chair: Tony Burton (2001).

Members of Wildlife and Countryside Link Bat Conservation Trust British Association of Nature Conservationists British Ecological Society British Mountaineering Council British Trust for Conservation Volunteers Butterfly Conservation Council for British Archaeology Council for National Parks Council for the Protection of Rural England(CPRE) Earthkind Environmental Investigation Agency Friends of the Earth Greenpeace Herpetological Conservation Trust International Fund for Animal Welfare Mammal Society Marine Conservation Society National Trust Open Spaces Society Plantlife Ramblers’ Association Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) The Shark Trust Universities Federation for Animal Welfare Whale & Dolphin ConservationSociety The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust The wildlife trusts Woodland Trust World Conservation Monitoring Centre Worldwide Fund for Nature – UK Young People’s Trust for the Environment& Nature Conservation Youth Hostels Association (England & Wales) Zoological Society of LondonThe special interest groups

The British Association of Nature Conservationists (BANC)

BANC was founded in 1979, and acts mainly as a forum for practising conservationists and planners through its influential journal, Ecos. Something of a trade journal, Ecos usually contains short articles on a wide range of conservation-related subjects, as well as news and reviews. BANC also holds conferences on particular topics, and publishes pamphlets on issues ranging from conservation ethics to feminism.

The British Trust for Conservation Volunteers (BTCV)

Established as the Conservation Corps in 1959, the BTCV organises practical tasks for people who wish ‘to roll up their sleeves and get involved’. A sister organisation was formed in Scotland in 1984. It runs some 200 courses each year for up to 130,000 volunteers on habitat management, such as footpath maintenance, fencing, hedge laying and dry-stone walling, along with wildlife gardening and developing leadership skills. It also works in partnership with local authorities and with government schemes such as the Millennium Volunteers. BTCV organises weekend residential projects and ‘Natural Break’ working holidays; for example, 29,000 volunteers assisted the National Trust to the tune of 1.7 million hours in 1994-95, ‘the equivalent of one thousand full-time staff’. Among its publications is The Urban Handbook, a guide to community environmental work. Its hands-on, open air, communal approach appeals particularly to the young. Its quarterly newsletter is Greenwork. Mission: ‘Our vision is of a world where people value their environment and take practical action to improve it.’

Head office: 36 St Mary’s Street, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX10 OEU.

British Trust for Ornithology (BTO)

The BTO was established in 1933 as a research and advisory body on wild birds. Its main task is the long-term study and monitoring of British bird populations and their relationship with the environment. From just one full-time administrator in the 1960s, it has grown into a leading scientific institution with a staff of over 50 and an annual income of nearly £2 million, mainly from funds and appeals. The Trust’s work is a fusion of ‘amateur enthusiasm and professional dedication’, its members acting as a skilled but unpaid workforce. Among its many schemes are the long-running Common Bird Census and its replacement, the Breeding Bird Survey, which it runs jointly with the RSPB and JNCC. Other projects include a Nest Record Scheme, the Seabird Monitoring Programme, special surveys of wetland, grassland and garden birds, the census of special species such as skylark and nightingale, and the administration of the National Bird Ringing Scheme. The Trust also helps organise special events such as the recent Norfolk Birdwatching Festival, and contributes to bird study internationally. It publishes the world-renowned journal Bird Study, currently reaching its 48th volume, as well as a bimonthly newsletter, BTO News, and a quarterly magazine, Bird Table. Membership: 11,490. Mission: to ‘promote and encourage the wider understanding, appreciation and conservation of birds through scientific studies using the combined skills and enthusiasm of its members, other birdwatchers and staff.

Address: The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU.

Director: Dr Jeremy Greenwood.

Butterfly Conservation

Although we have so few species compared with most other European countries, butterflies are next to birds in popularity. In 1968 the British Butterfly Conservation Society (BBCS) was formed by Thomas Frankland and Julian Gibbs with the purpose of saving rare species from extinction and promoting research and public interest in butterflies. Growth was slow at first, but the Society took on the responsibility for the Butterfly Monitoring Scheme in 1983, and acquired its first nature reserve three years later. Since shortening its name to ‘Butterfly Conservation’ in 1990, the society has acquired considerable in-house expertise. With 10,000 members, it is said to be the largest conservation body devoted to insects in all Europe.

With an office in Dorset, probably today’s richest county for butterflies, Butterfly Conservation has a network of 31 branches throughout Britain and runs 25 nature reserves. It has also opened an office in Scotland. It is funded mainly by grants, corporate sponsorship and legacies. The Society’s most substantial achievement to date is its ‘Butterflies for the New Millennium’ project, a comprehensive survey of British butterflies involving thousands of recorders in Britain and Ireland, culminating in the publication of a Millennium Atlas in 2001 (Asher et al. 2001). Butterfly Conservation is the lead partner for several Species Action Plans, and administers some 30 other projects under its ‘Action for Butterflies’ banner. The Society also helps to monitor butterfly numbers using fixed transects (‘every butterfly counts, so please count every butterfly’), and contributes to butterfly conservation internationally; Martin Warren, its conservation director, co-authored the European Red Data Book. The Society publishes a quarterly magazine, Butterfly Conservation, and a range of booklets. In 1997, it helped to launch a new Journal of Insect Conservation. Aim: ‘Working to restore a balanced countryside, rich in butterflies, moths and other wildlife’.

Address: Manor Yard, East Lulworth, Wareham, Dorset BH20 5QP.

Chairman: Stephen Jeffcoate. Head of Conservation: Dr Martin Warren.

The Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group (FWAG)

FWAG was the brainchild of an informal gathering of farmers and ecologists at Silsoe College, Bedfordshire, in 1969 to work out how to fit conservation into a busy, modern farm. (For a full account see Moore 1987.) Under the auspices of FWAG a network of local farm advisers was established, generally of youngish people with a degree in ecology but with a background in, or at least knowledge of farming. By 1984, some 30 advisers had been appointed, and a Farming and Wildlife Trust was launched to fund the local FWAGs, supported by grants from the Countryside Commissions and other bodies, as well as by appeals. The FWAG idea has helped to break down stereotypes and change farming attitudes. Its advisers became skilled at spotting ingenious ways of preserving wild corners, and planting copses and hedges without harming the farmer’s pocket. A notable achievement was the creation or restoration of thousands of farm ponds. An external review indicated that FWAG is strongly supported by farmers, with a high rate of take-up of advice.

Some saw the FWAG project as essentially a public relations exercise, and criticised it for being too much under the thumb of the National Farmers’ Union and hence reluctant to criticise modern farming methods. However, it has undoubtedly helped to find a little more space for wildlife on innumerable farms – up to 100 farms per county per year – and has built bridges with the farming community by organising farm walks and training visits, and appearing at the agricultural shows.

Head office: The National Agricultural Centre, Stoneleigh, Kenilworth, Warwickshire CV8 2RX.

Marine Conservation Society

Formed in 1978 (‘Underwater Conservation Year’), this small but active national charity with 4,000 members is dedicated to protecting the marine environment and its wildlife, especially in the offshore waters of the British Isles. It publishes an annual Good Beach Guide, an Action Guide to marine conservation and a ‘species directory’ of all 16,000 species of flora and fauna found in British waters. It campaigned successfully for protection for the basking shark, and is the ‘lead partner’ for the UK marine turtles Species Action Plan. Among its multifarious activities for volunteer divers and beachcombers are ‘Seasearch’, a project to map UK marine habitats, a schools project called ‘Oceanwatch’, and an adopt-a-beach project for communal cleaning up. Another project, ‘Ocean Vigil’, records cetaceans and sharks. Fund raising is called ‘Splash for Cash’. Internationally, the Society surveys coral reefs in the Red Sea and Sri Lanka, and is helping the Malaysian government to establish a marine wildlife park at the Semporna Islands. Members receive a quarterly news magazine, Marine Conservation. Its slogan: ‘Seas fit for life’.