Полная версия

Nature Conservation

In some areas, especially in island communities, SSSIs were seen as an alien imposition. In Islay, teeming with wildlife, a severe dose of SSSIs looked like a punishment for farming in harmony with nature. Things came to a head in the small matter of finding a source of peat for an Islay distillery as a substitute for Duich Moss, one of the best raised bogs in the Hebrides. A team of environmentalists led by David Bellamy, intending to plead the cause of peatland conservation, was howled down by angry islanders normally renowned for their hospitality and gentleness of manners. It was not that the community was against nature conservation, only that they did not enjoy being told what to do by a Peterborough-based quango (a place not particularly noted for its teeming wildlife).

Notifying SSSIs was a much more complicated business than anyone had foreseen. To begin with staff had to find out who owned the land, and even that could be a hornet’s nest with, in Morton Boyd’s words, ‘many untested claims to holdings, grazings and sporting rights’ (Boyd 1999). SSSIs were an absolute, bureaucratic system imposed on a system of tenure that was often the opposite: communal, fluid, and based on non-Westminster concepts of custom, neighbourliness and unwritten rules. Outsiders blundering into these matters could unwittingly set neighbour against neighbour. They could also make themselves very unpopular. Moreover some SSSIs were already under dedicated schemes for forestry or peat extraction, or an agricultural grant scheme. In the Outer Hebrides an EU-fund-ed Integrated Development Scheme was in progress, while in Orkney an Agriculture Department-funded scheme was encouraging farmers to reclaim moorland. The NCC often found itself outnumbered. When, in 1981, it opposed the extension of ski development into the environmentally sensitive Lurchers Gully in the Cairngorms (see Chapter 10), the NCC found itself ranged against the Highlands and Islands Development Board, Highland Regional Council, and sports and tourism lobbies, as well as local entrepreneurs. It won that particular battle but, in the Highlands and Islands at least, the NCC eventually lost the war.

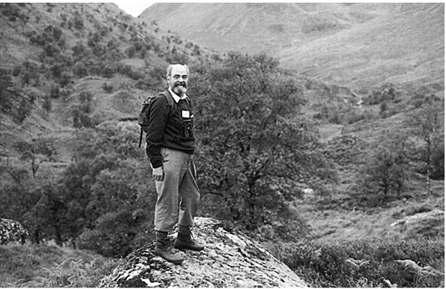

J. Morton Boyd, Scottish director of the NCC, at Creag Meagaidh, which he helped save from afforestation. (Des Thompson)

The break-up of the NCC

Replying to an arranged Parliamentary question on 11 July 1989, Nicholas Ridley told a near-empty House of Commons that he had decided to break up the Nature Conservancy Council. In its place he would introduce legislation for separate nature conservation agencies in England, Scotland and Wales. I well remember the shock. Just the previous week we had attended a ceremony to mark the retirement of Derek Ratcliffe, Chief Scientist of the NCC since its establishment 16 years before. ‘Things will never be quite the same again,’ we thought, little suspecting just how different they would be. I was in the canteen at the NCC’s headquarters at Northminster House as a rumour spread over the cause of the emergency Council meeting upstairs. The hurried patter of feet on the third floor, doors banging, chairs scraping, voices raised, all signalled unusual excitement. NCC’s chairman, Sir William Wilkinson, had, it seemed, been given a week’s notice of the announcement, but had not been allowed to tell anyone. He used the time to appeal to the Prime Minister, but she backed her minister. Council had had only one day’s official notice, although some of them did not seem very surprised, and a few welcomed it. We, the staff, were caught completely unawares. As Forestry and British Timber magazine gloated, ‘it was, no doubt, to spare the NCC the horrors of anticipation that the Ridley guillotine crashed down upon it last week. There was no warning, no crowds, no tumbrils, no (or very little) mourning. The end of the Peterborough empire came silently and swiftly’.

No mourning from foresters may be, but it sent a seismic shudder, shortly to be followed by an outpouring of rage, through the nature conservation world. ‘At no time was NCC given notice of such extreme dissatisfaction with its performance as to register a threat to its corporate existence’, wrote Donald Mackay, a former undersecretary at the Scottish Office (Mackay 1995). The only clue in Ridley’s statement was that there were apparently ‘great differences between the circumstances and needs of England, Scotland and Wales…There are increasing feelings that [the present] arrangements are inefficient, insensitive and mean that conservation issues in both Scotland and Wales are determined with too little regard for the particular requirements in these countries’. Evidently, then, events in Scotland and Wales had propelled the announcement.

The sentence had been done in haste. Ridley was about to move from Environment to Energy, where he was sacked a year later for making offensive remarks about the Germans. Nothing had been thought through. The implication was that, as far as nature conservation was concerned, England, Scotland and Wales would now go their separate ways, but left hanging was the not unimportant matter of who would represent Britain internationally and who would referee common standards within the new agencies. Moreover, far from being more efficient, a devolved system implied endless duplication (actually, triplication) and waste. ‘What would you rather have?’ asked Wilkinson, ‘a peatland expert for Great Britain, or three under-resourced experts in England, Scotland and Wales? It’s obvious isn’t it?’ Behind Wilkinson’s disappointment and frustration was the knowledge that his Council had been about to introduce a ‘federal’ system of administration that, he thought, would largely have answered the genuine problems being experienced in Scotland and Wales.

Some of the smoke from Ridley’s 1989 bombshell has since cleared. At issue was the NCC’s unpopularity in Scotland, and in particular its opposition to afforestation. Things came to the crunch in 1987 when, alarmed at the rate of afforestation in the hitherto untouched blanket bogs of far away Sutherland and Caithness (see Chapter 7), the NCC called for a moratorium on further planting in the area. Fatally, the NCC decided to hold its press conference in London, not in Edinburgh or Inverness, lending substance to the accusation that the NCC was an English body, with no right to ban development in Scotland, especially when jobs were at stake. It is alleged that there was a reluctance on the part of the NCC’s Scottish headquarters to host the press conference; its Scottish director, John Francis, had taken diplomatic leave. The Scottish media took more interest in a spoiling statement by the Highlands and Islands Development Board, whose chief took the opportunity to call for a separate Scottish NCC. The Scottish press took up the cry, and from that day on another ‘split’ was probably inevitable. The MP Tam Dalyell was in no doubt that this was why the NCC was broken up: ‘It originated out of a need that had nothing whatsoever to do with the best interests of the environment. It was about another need entirely, that is, the need for politicians to give the impression that they were doing something about devolving power to the Scots as a sop to keep us happy’ (Dalyell 1989).

Just as the Scots resented ‘interference’ from Peterborough, so the Secretary of State for the Environment resented having to pay for things outside his direct control (for DoE’s writ ran only in England and Wales). According to Mackay, Ridley, growing alarmed at the anticipated costs of compensating forestry companies in Caithness, suggested to his Cabinet colleague, Malcolm Rifkind, that Scotland should receive its own conservation agency and shoulder the burden itself. With the Conservative party’s popularity at an all-time low in Scotland, Rifkind must have seen political advantages in such a gesture, and ordered his Scottish Development Department to prepare a plan for detaching the Scottish part of the NCC and merging it with the Countryside Commission for Scotland. The case for Scotland automatically created a similar case for Wales. It seems, though, that Wales received its own devolved agency without ever having asked for one.

The secrecy in which all this took place is surprising, but it enabled ministers to rush the measure through before the inevitable opposition could get going – an early example of political ‘spin’. The NCC had few influential friends north of the Border, where voluntary nature conservation bodies were weak. Moreover, the afforestation issue had encouraged separatist notions among the NCC’s own Scotland Committee and staff. Broadly speaking they saw the future of wild nature in Scotland in terms of sustainable development and integrated land use, which in some vague way should reflect the value-judgements of the Scottish people. It made little sense to draw lines around ‘sites’ in the Highlands where wild land was more or less continuous. Hence they saw more merit in processes – making allies and finding common ground – than in site-based conservation, which, as they saw it, only served to entrench conflict. That, at least, is what I construe from the statement of the chairman of the NCC’s Scotland Committee, Alexander Trotter, at the break-up, that ‘It has been clear to me for some time that the existing system is cumbersome to operate and that decision making seemed remote from the people of Scotland’.

Some of the opposition to the break-up was blunted by the obvious appeal of combining nature and landscape conservation in Scotland and Wales. Many believed that the severance of wildlife and countryside matters back in 1949 had been a fundamental error, and that in a farmed environment like the British countryside they were inseparable. However, Ridley refused to contemplate their merger in England, arguing that the administrative costs would outweigh any possible advantages (a view the Parliamentary committee concurred with when the question was reopened in 1995). The main objection, apart from the well-founded fear that science-based nature conservation had suffered another tremendous, perhaps fatal, body blow, was the void that had opened up at the Great Britain level. Following a report by a House of Lords committee under Lord Carver, Ridley’s successor, Chris Patten accepted the idea of a joint co-ordinating committee to advise the Government on matters with a nationwide or international dimension. This became the Joint Nature Conservation Committee or JNCC, a semiautonomous science rump whose budget would be ‘ring-fenced’ by contributions from three new country agencies. Some of the NCC’s senior scientists ended up in the JNCC, only to find they were scientists no longer but ‘managers’.

Creating the new agencies took many months, during which the enabling legislation, the (to some, grossly misnamed) Environment Protection Bill, passed through Parliament, and the NCC made its internal rearrangements. Separate arrangements were needed under Scottish law, and so an interim body, the Nature Conservancy Council for Scotland was set up before the Scottish Natural Heritage was established by Act of Parliament in 1992. From that point onwards, the history of official nature conservation in Britain diverges sharply. Because of the interest in the new country agencies’ performance, I will present them in some detail. They form an interesting case study of conservation and politics in a devolved government. In Scotland and Wales particularly it has led to a much greater emphasis on popular ‘countryside’ issues, and less on wildlife as an exclusive activity. In England, too, there have been obvious attempts to trim one’s sails to the prevailing wind, with an ostentatious use of business methods and a culture of confrontation-avoidance. Let us take a look at each of them, and the JNCC, starting with English Nature.

NCC’s spending in 1988 (in £,000s)

Income From government grant-in-aid 36,105 Other income 2,461 (mainly from sales of publications rents and research undertaken on repayment terms) £38,566 Expenditure Staff salaries and overheads 14,310 Management agreements 7,287 Scientific support 4,992 (including 3,736 for research contracts) Grants 2,510 (made up of 1,109 for land purchase, and the rest staff posts and projects, mainly to voluntary bodies) Maintenance of NNRs 1,399 Depreciation 1,089 Other operating charges 7,280 (e.g. staff support, books and equipment, accommodation, phones) £38,867From NCC 15th Annual Report 1 April 1988-31 March 1989

English Nature

Headquarters: Northminster House, Peterborough PE1 1UA.

Vision: ‘To sustain and enrich the wildlife and natural features of England for everyone’.

Slogan: ‘Working today for nature tomorrow’.

English Nature began its corporate life on 2 April 1991 (April Fool’s Day was a public holiday that year) with a budget of £32 million to manage 141 National Nature Reserves, administer 3,500 SSSIs and pay the salaries of 724 permanent staff. Most of the latter were inherited from the NCC, including a disproportionate number of scientific administrators, and only 90 were new appointments. EN’s Council was, as before, appointed on the basis of individual expertise, and intended to produce a balance of expertise across the range of its functions. However, they were now paid a modest salary and given specific jobs to do. From 1996, under the new rules established by the Nolan Report, new Council posts were advertised. All of them had to be approved by the chairman, a political appointee. What was noticeable about EN’s first Council was that only one was a reputable scientist. None were prominently affiliated to a voluntary body, nor could any of them be described as even remotely radical. This Council was less grand than the NCC’s: fewer big landowners, no wildlife celebrities, and no MPs. In 1995, at the request of Lord Cranbrook, EN’s chief executive, Derek Langslow, became a full member, unlike his predecessors who just sat in on meetings and spoke when required. This made him a powerful figure in English Nature’s affairs.

English Nature inherited the structure of the NCC, with its various administrative branches, regional offices and headquarters in Peterborough. Externally the change from NCC to English Nature was brought about simply by taking down one sign and erecting another. An agency designed to serve Great Britain could, with a little readjustment, easily be scaled down to England alone. English Nature could, if it wished, carry on with business as usual. Even its official title remained the Nature Conservancy Council (for England); the name ‘English Nature’ was only legalised in 2000.

In the event, it opted for a radical administrative shakedown. The new administration was keen to present a more businesslike face to the world with a strategic approach in which aims would be related to ‘visions’ and goals, and tied to performance indicators monitored in successive corporate plans. A deliberate attempt was made to break down the NCC’s hermetic regions and branches into ‘teams’, each with their own budget and business plan. At Northminster House, partition walls were removed, and the warren of tiny offices replaced by big open plan rooms in which scientists, technicians and administrators worked cheek byjowl. There were also significant semantic changes. English Nature saw landowners and voluntary bodies as its ‘customers’; its work as a ‘service’ – one of its motto-like phrases was that ‘People’s needs should be discovered and used as a guide to the service provided’. Its predecessors had considered themselves to be a wildlife service. English Nature was overjoyed to receive one of John Major’s Citizen Charter marks for good customer service. Henceforward English Nature’s publications bore the mark like a medal.

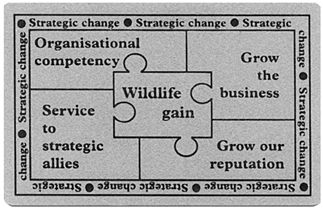

American corporatism comes to nature conservation. This card, carried by English Nature staff in the late 1990s, borrows the language of big corporations (‘strategic change’, ‘inside track’, ‘empower/accredit’).

English Nature’s tougher organisation was mirrored in its presentations. Its annual reports seemed more eager to talk up the achievements of English Nature as a business than to review broader events in nature conservation. Looking back at EN’s first ten years, Michael Scott considered that the ‘strategic approach’ had engendered more bureaucracy along with tighter administrative control: ‘Senior staff talk more about recruitment levels, philosophy statements, strategic management initiatives and rolling reviews than about practical policies on the ground’ (Scott 1992). Nor was EN’s much-vaunted ‘philosophy statement’ exactly inspiring to outsiders, with its talk of ‘developing employee potential’ and achieving ‘efficient and effective use of resources through the operation of planning systems’. To those, like the postgraduates who listened in on EN’s lectures on corporate strategy, it might have sounded impressively professional, but, with the best will in the world, it didn’t sound much fun; and to some they seemed to have more to do with what happened behind the dark-glass windows of Northminster House than out there in the English countryside.

The internal changes were not as radical as they looked. English Nature’s statutory responsibilities were much the same as the NCC’s, and the focus was still on SSSIs, grants and nature reserves. But now that the SSSI notification treadmill had at last ceased to grind, staff could turn their attention towards more positive schemes and participate more in ‘wider countryside’ matters. English Nature reorganised its grant-aid projects into a Wildlife Enhancement Scheme for SSSIs and a Reserves Enhancement Scheme for nature reserves. Both were based on standard acreage payments, and every attempt was made to make them straightforward and prompt. They were intended to be incentives for wildlife-friendly management, for example, low-density, rough grazing on grasslands and heaths, or to fund management schemes on nature reserves. The take-up rate was good. The trouble was that they were never enough to cover more than a fraction of SSSIs. Meanwhile EN’s grant-aid for land purchase virtually dried up. Country wildlife trusts turned to the more lucrative Heritage Lottery Fund instead.

English Nature also took the lead on a series of themed projects to address important conservation problems. In each, the idea was that EN would provide the administration and ‘strategic framework’ for work done mainly by its ‘partners’. The first, a ‘Species Recovery Programme’ to save glamorous species such as the red squirrel and fen raft spider from extinction, was up and running within weeks. The following year, it introduced a Campaign for Living Coast, arguing that it was wiser in the long run to work with the grain of nature than against it. In 1993 came a Heathland Management Programme, the start of a serious effort to conserve biodiversity on lowland heaths by reintroducing grazing. In 1998, this swelled into an £18 million Tomorrow’s Heathland Heritage programme, supported by the Heritage Lottery. In 1997, English Nature proposed an agenda for the sustainable management of fresh water, detailing the ‘action required’ on a range of wildlife habitats, and started another multimillion pound project on marine nature conservation, part-funded by the EU LIFE Programme. More controversial was EN’s division of England into 120 ‘Natural Areas’ based on distinctive scenery and characteristic wildlife. The basic idea was to show the importance of wildlife everywhere and emphasise its local character. Each area had its own characteristics and ‘key issues’ which, for the South Wessex Downs, included the restoration of ‘degraded’ downland and fine-tuning agri-environmental schemes to benefit downland wildlife. The critics of ‘Natural Areas’ were not against the idea as such (though some Areas were obviously more of a piece than others) but saw it as a long-winded way of stating the obvious, involving the production of scores of ‘Natural Area Profiles’ replete with long lists of species. As with the Biodiversity Action Plan, part of the underlying purpose seems to be to foster working relations with others, especially local authorities.

Like its sister agencies, English Nature wanted to present positive ideas for helping nature and avoid the wrangles of the 1980s. It did so with considerable success, helped by the fact that conservation was gradually becoming more consensual. But the awkward fact remained that, by EN’s own figures, between a third and a half of SSSIs were in less than ideal management. Moreover, in its zeal to work positively with ‘customers and partners’, some found English Nature too willing to compromise and to seek solutions in terms of ‘mitigation’. An early instance was the ‘secret deal’ with Fisons over the future of peatland SSSIs owned or operated by the company. Fisons had agreed to hand over 1,000 hectares of the best-preserved peatlands to English Nature in exchange for a promise not to oppose peat extraction on the remaining 4,000 hectares. Those campaigning actively to stop industrial peat cutting on SSSIs were excluded from the negotiations, and left waiting on the pavement outside the press conference. Whatever tactical merit there might have been in a compromise agreement, the protesters felt that EN had capsized their campaign. English Nature argued that to try and block all peat cutting on SSSIs, as the campaigners wanted, would have involved the Government in compensation payments costing millions, and put 200 people out of work. To which, the campaigners replied that that was the Government’s business, not English Nature’s. And who exactly were the ‘partners’ here – the peat industry or the voluntary bodies?

It was English Nature’s misfortune to be seen to be less than zealous when an issue became headlines, such as the Newbury bypass (p. 217) or the great newt translocation at Orton brick-pits (p. 207). Of course, as a government body EN had to be careful when an issue became politically sensitive, but on such battlegrounds it was easy to see it as ‘the Government’ and bodies like the WWF or Friends of the Earth as the opposition; it contributed to the tense relationship between the agencies and the voluntary bodies at this time. The year 1997 was a particularly difficult one for English Nature. It failed to apply for a ‘stop order’ at Offham Down until prodded by its parent department (pp. 96-7). It wanted to denotify parts of Thorne and Hatfield Moors which would clearly enable the peat producers to market their product more widely. This ill-timed decision led to an embarrassing public meeting at Thorne, when chief executive Langslow was all but booed off the stage, followed by an enforced U-turn after the minister politely advised English Nature to think again. EN’s latest strategy, ‘Beyond 2000’, was ill-received, despite its clumsy attempts to involve the voluntary bodies with questions like ‘How can we improve our measurement of EN’s contribution to overall wildlife gain’ (uh?). On top of all that, in November WWF published a hostile critique of English Nature, A Muzzled Watchdog?, based on a longer report on all three agencies I had written for them. It was not so much what it had to say as the unwonted sight of one conservation body publicly attacking another that attracted attention. EN’s refusal to comment, apart from some mutterings about ‘inaccuracies’, did not help its case.