Полная версия

Nature Conservation

Some millennial stocktaking

About 30 years ago, when I was just setting out into the nature conservation world, we used to be slightly apologetic about British wildlife. Almost anything we had, other European countries had better, we thought. Britain has few endemic species worth mentioning, apart from Primula scotica (the Scottish primrose) and the good old red grouse (which, ornithologists insisted, was the same species as the bigger, better-looking continental willow grouse), nor much of world importance, apart from the grey seal (which we were then culling by the hundred) and maybe the gannet. Since then, Britain’s stock has risen considerably. We have places such as the New Forest, St Kilda and the Cairngorms, which are important after all, and more old trees than anywhere north of the Alps. Our marine life, estuaries and Atlantic oak woods are pretty special, and Britain is right at the top of the European liverwort league. I was slightly staggered to hear we have 40 per cent of Europe’s wrens. If Britain sank beneath the waves, quite a lot of species would be sorry.

Britain’s wildlife is important in another way. Natural history is very popular – we have 4,000 RSPB members for every species of breeding bird – and we are very good at it. (Who wrote The Origin of Species? Who lived at Selborne?) Britain probably has the best documented wildlife in the world – all right, we might tie with the Dutch and the Japanese. Our 60-odd butterflies are nothing on the world stage, but the expertise acquired in studying them has been exported worldwide. British bittern experts are in demand internationally, though we have only a handful of bitterns. We might not be much good at protecting wildlife, but we certainly know a lot about it. How well, in fact, are our wild animals and plants faring at the start of the new millennium?

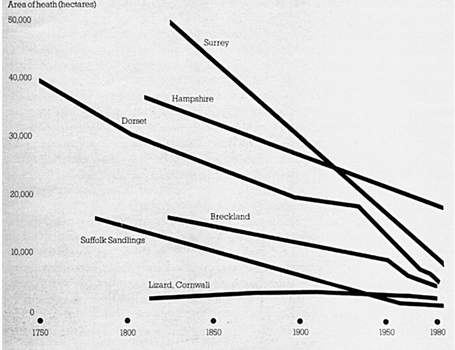

There are some grounds for optimism. The loss of wild habitats with which we are sadly so familiar can now be seen in a historical context – as a feature of the domination of intensive agriculture (including forestry) between 1940 and 1990. The statistics of habitat loss put together by the NCC in 1980 have been much repeated, and certainly paint a grim picture. I will not march through them all again, since statistics tend to have a numbing effect on our jaded twenty-first century minds, and they are meaningless without context. For example, what does the loss of 95 per cent of ‘neutral grassland’ mean? It does not tell us whether all the lost ground was of importance for wildlife, nor whether what remains is of the same value as it was. It does, however, imply that something pretty far-reaching has happened to the landscape, and that perhaps only one unimproved meadow in 20 has survived. Meadows are the biggest losers of the habitat loss stakes, but we have lost almost as much wet peatland and ‘acid grassland’, mainly on former commons and village greens, and about half the chalk downs and natural woods that existed before 1939.

The red grouse, Britain’s most celebrated endemic animal, adapted for life on heather moors. (Derek Ratcliffe)

The official nature conservation agencies publish annual estimates of habitat loss and damage in their annual reports. The loss is ongoing, and although it has fallen since the peak in the agricultural high noon of the 1970s, there is now less habitat to damage. The problem with the figures is that, however they are defined, damage assessment is relative. Some types of ecological damage, such as eutrophication, need a trained eye, while others, such as surface disturbance, may look like damage, but may be harmless or even beneficial. Moreover, the agencies have a bad habit of changing their method of calculation from year to year, and since devolution it has become maddeningly difficult to compare what is happening in England with Scotland or Wales or vice versa. All the same, the losses indicate that statutory protection of wild habitats has not been as effective as many had hoped.

The decline of lowland heath in six parts of England over two centuries. (From Nature Conservation in Great Britain, NCC 1984)

The concensus at the turn of the millennium is that loss and damage has slowed considerably and for some habitats may have halted. SSSIs have acquired a greater land value because of the grants they now attract, and SSSI protection is also more effective than formerly. Also more of them are owned or managed by conservation bodies or benign private owners. For at least one well-documented habitat, hedges, removal is now offset in terms of length by newly planted or repaired hedges (quality is not assessed). Hedgerow removal peaked between 1955 and 1965, when many of the open barley prairies of eastern England were created. The process went on in lower gear, with about 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometres) of hedges removed per year, mainly by arable farmers, but also for urban development, roadworks and reservoirs. The Government’s Countryside Survey found virtually no overall decline in hedges between 1990 and 1998, except in neglected ‘remnant hedges’: about 10,000 kilometres (2 per cent) of hedges were removed, and a similar amount planted. But the survey found evidence for some loss of plant diversity, especially tall grasses and ‘herbs’. The reason why hedges have stabilised is because government no longer pays the farmer to pull them up, but pays him to plant them. Stewardship and other agri-environmental schemes are the main reason why hedges are still planted.

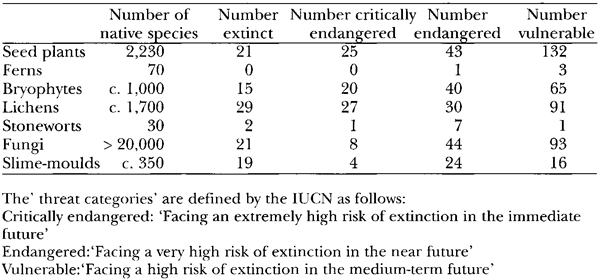

We have lost a lot of wildlife habitat, but conservation bodies saved many of the best places, and the story is by no means all doom and gloom. Today’s problem, which I will turn to in the last chapter especially, is the reduction in habitat quality and diversity, which is all the more insidious because it is hard to measure precisely. When we turn to species, the overall picture is the same. Many species – possibly most species – have declined over the past half-century, but relatively few have become nationally extinct. Some once believed extinct have since reappeared, or have been reintroduced in biodiversity schemes. The best-known victim of the past half-century, the large blue butterfly, has been reintroduced from Swedish stock, which closely resembles the lost British race. Thanks to thorough research and ground preparation by Jeremy Thomas and David Simcox, the project has been a resounding success, and several introduction sites are now open to the public. But there is a very large disparity between the small number of recorded extinctions and the much larger number that seem to be approaching extinction. For example, the JNCC considers that about 20 native wild flowers are extinct (though my own tally makes it nearer ten), but some 200 face extinction in the short or medium term. Similarly, some 29 lichens are considered extinct, but 148 are ‘endangered’ or ‘vulnerable’. The implication is that conservationists are good at saving species at the last ditch, but bad at preventing them from getting that far.

The status of plants and fungi in Britain (based on details from the JNCC’s website)

Invertebrates are often ‘finely tuned’ to their environment and are more vulnerable to change than birds or many wild plants. Their fortunes have varied from group to group. Ladybirds and dragonflies are not doing too badly – ladybirds like gardens, dragonflies like flooded gravel pits – but things are currently looking grim for wood ants, and some bumblebees and butterflies. In a recent review I learned that some 200 species of flies (Diptera) are considered endangered and another 200 or so vulnerable (Stubbs 2001). Granted that flies are mysterious things with rather limited appeal, one wonders what the implications of 400 nose-diving flies could be. If 400 subtle, specialised ways of living are under threat, the environment must be quietly losing variety, losing tiny facets of meaning, like a little-read but irreplaceable book being nibbled away bit by bit by bookworms. Interestingly the author of this review blamed some of the losses on conservationists – ‘inappropriate decisions by amenity and conservation organisations’ – as much as farmers and developers. Tidying up is bad for flies.

Not all species are fated to decline. In a detailed assessment of Britain’s breeding birds by Chris Mead (Mead 2000), the accounts are surprisingly well balanced: some 118 species are doing well and 86 are doing badly. However, the fortunes of different species fluctuate, reflecting the lack of stability in the modern countryside. Some once rare birds, such as Dartford warbler, red kite and hobby, are among those that Mead awards a smiling face, meaning that they are doing well – stupendously well in the case of the kite. Among other smiling faces are gulls, geese, many water birds and seabirds and most raptors. Several species have colonised Britain naturally, notably little egret, Cetti’s warbler and Mediterranean gull, and others, such as spoonbill and black woodpecker, may be on the brink of doing so. The commonest bird in 2000 was the wren, which has benefited from the recent run of mild winters and thrives in suburban gardens. Conservation schemes have probably saved corncrake, cirl bunting, stone curlew, and perhaps woodlark, for now. Perhaps the best news of all is the recovery of the peregrine falcon from a dangerous low in 1963, following the ban on organochlorine pesticides, though it still faces persecution in parts of Britain. We are now quite an important world stronghold for peregrines.

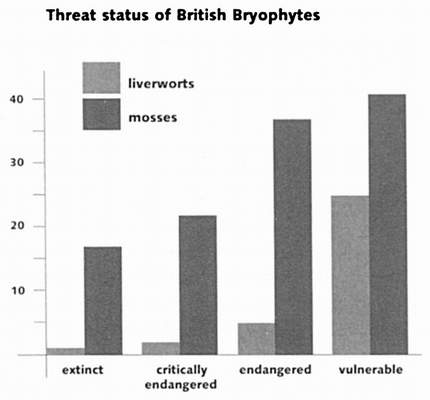

About 14 per cent of our moss and liverwort flora is considered vulnerable, endangered or extinct. This is JNCC’s projection of their respective ‘threat status’. (JNCC)

The losers – Mead’s unhappy faces – include familiar farmland birds such as skylark, song thrush, linnet, grey partridge, lapwing and snipe. Even starling and house sparrow have declined markedly. The problem they all face is lack of food on today’s intensively managed, autumn-sown cereal fields. The red-backed shrike has ceased to breed, and the red light is showing for black grouse and capercaillie, which are finding life difficult in the overgrazed moors and upland woods (and no good just putting up deer fences: the capercaillie crashes straight into them). Interestingly, small birds are faring worse, on balance, than big ones. A birder of the 1960s would be shocked at what has happened to lapwings or golden plovers, but pleased and probably surprised at how well many comparatively rare species have adapted to a changing environment. Stranger things lie just ahead. Try imagining green parakeets stealing the food you left out for the disappearing starlings.

Like birds, some of the smaller mammals have declined more than the big ones. Some carnivores, such as polecat and pine marten, are more widespread today than they were in 1966. The grey seal is much more numerous, thanks entirely to the cessation of regular culling. Deer are also more numerous, though this is a mixed blessing. Though increasing, the red deer is threatened genetically by hybridisation with the increasing, introduced sika deer, and may soon be lost as a purebred species. Bats, as a class, have declined. The best counted species, the greater horseshoe bat, is believed to have declined by 90 per cent during the twentieth century. The present population is estimated to be only 4,000 adult individuals. Only 12 colonies produce over ten young per year (Harris 1993). Rabbits have made a slow recovery from myxomatosis, and are back to about 40 per cent of their original abundance, but occur more patchily than before. The otter has staged a slow recovery, aided by reintroductions, but may take another century to recover its former range across eastern Britain. The real losers are red squirrel and water vole, both victims of introduced mammals. Dormouse and harvest mouse are also declining, apparently because of changes in woodland and agricultural land that reduce food availability. Our rare ‘herpetiles’ (i.e. reptiles and amphibians), sand lizard, smooth snake and natterjack toad, have benefited from site-based conservation and a zealous British Herpetological Society. Most of our freshwater fish seem fairly resilient, but the burbot has been lost and our two migratory shads reduced to rarity status because of pollution and tidal barrages. The char, which likes clear, cold water, has disappeared from some former sites. The powan faces an uncertain future in Loch Lomond following the accidental introduction of a competitor, the ruffe, which eats its eggs. Its relative, the pollan of Lough Neagh, is now threatened by carp, casually introduced nearby to please a few anglers. In the sea, we, with the help of our European friends, have overfished herring, cod and 22 other species, and almost wiped out the skate.

We should not, however, judge the success of nature conservation measures solely by changes in the numbers of well-known animals. Birds are important, because everyone likes them, and because losses and gains among such well-recorded species are important clues to what is happening to their environment. In nature conservation, every bird is a miner’s canary. But birds are almost too popular. In the 1960s, many field naturalists specialised in relatively obscure orders, pond and shore life, and difficult insects, such as beetles or bugs. Today, an oft-heard complaint is that taxonomists are an ageing and diminishing band, and that the few professional ones are nowadays tied up in administrative tasks. The number of people who can identify protozoa, or diatoms, or worms is probably fewer now than a century ago. As a result, we have no idea what is happening to them. All too often, biodiversity has been lost from ignorance, even on nature reserves. Britain’s nature reserves are run by people who would know a hawk from a handsaw at a thousand paces, but to whom invertebrates are just wriggly things that live in bushes.

Discovering where the wildlife is

In the 1960s, the study of British natural history was in a reasonably healthy state, better in some respects than it is today. Entomology and microscopy were less popular than in their late Victorian heyday, but with the advent of cheap, lightweight binoculars, birdwatching was growing in popularity, and ecology was being taught at schools and universities. Serious naturalists were making connections between a species and its environment, which led, by extension, to conserving and managing natural habitats. Naturalists were well catered for by a wide range of books in print, not least by 40-odd volumes in the New Naturalist library. The now universal field guide had made an appearance, but there were also handbooks on beetles, spiders, bugs, grasshoppers and even centipedes and rotifers, at affordable prices. Naturalists were not infrequently equipped with a hand lens, and specimen collecting was not yet considered a crime. Television natural history had begun, with programmes such as Look and Survival and, though still in black-and-white, had less manic, less dumbed-down presenters and they were more often about wildlife near at home.

Much less was known about wildlife habitats and sites. Although some places had been thoroughly explored by naturalists, with long typed lists of species bound in massive ledgers, there had been few systematic surveys of habitats or species. The first attempts to census and record the distribution of species had been made in the 1920s and 1930s for certain colonial birds, such as heron and rook. However, the most important mapping scheme to date had been for wild flowers. In 1962, the Botanical Society of the British Isles published the Atlas of British Flora, which mapped the nationwide distribution of some 1,400 native or naturalised wild flowers and ferns using dot-maps based on a grid of 10 x 10 kilometre squares. What made the atlas possible was the invention of punch-card computers. It was all done without sizeable grant-assistance or central organisation, although the production of such atlases was later facilitated by a Biological Records Centre, established at Monks Wood under Franklyn Perring and, later, John Heath.

Similar atlases have since been produced and published for other plants and animals, including lichens (from 1982), butterflies (1984), bryophytes (from 1991), dragonflies (1996), grasshoppers (1997) and molluscs (1999). Pre-eminent among them are the bird atlases, The Atlas of Breeding Birds (1976) and The Atlas of Wintering Birds (1986). The production of a second breeding bird atlas recording breeding birds in 1993 was all the more valuable because it enabled an analysis of change over a 20-year period, providing a temporal dimension to the maps. The same has been done for only one other group, the butterflies, which received perhaps the most lavish and detailed atlas of all, The Millennium Atlas, in 2001. Distribution maps of many British species are now published on the Internet, via the National Biodiversity Network.

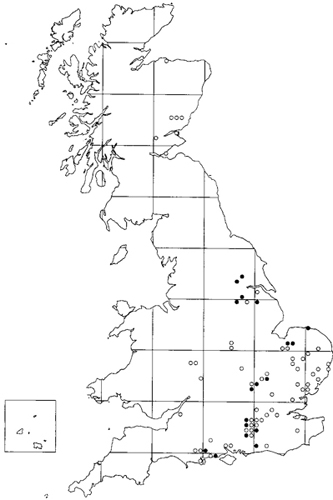

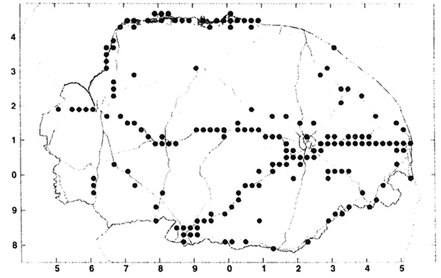

Of course, the relatively crude scale of 10 x 10 kilometres does not record actual sites (and so can make a species appear more frequent than it really is). Maps of vascular plants and butterflies have been published on finer scales, and a 2 x 2 kilometre ‘tetrad’ is now standard for county-scale maps (and represents a stupendous recording effort by local naturalists). These reveal some of the detail of actual distribution, fine enough to show the course of rivers and different strata and soil types. Some rare species have been mapped by actual sites; visually, the problem of actual-scale maps is that the ‘dots’ all but disappear – fly-specks on a blank canvas. Some insects, including butterflies, seem to occupy tiny patches of land, measured in metres rather than kilometres.

The venerable Victorian tradition for recording the wild plants of a county has been given a new lease of life by computer-based mapping. Grid-mapping was used in most of the county floras published since 1960. Their compilation by dedicated amateur naturalists, sometimes working as a team, sometimes, especially in the more remote regions, representing a titanic solo effort, is one of the wonders of British natural history. The majority of English counties have a flora published during the past 20 years, generally mapped on a fine 2 x 2 kilometre scale. By tradition they also include an overview of the county’s natural vegetation, progress in conservation and potted biographies of local botanists. The recent Flora of Cornwall has an accompanying CD-Rom holding the entire database of records. Some, such as The Flora of Dorset, record mosses, lichens and even fungi, as well as vascular plants. Others, such as A Flora of Norfolk and A Flora of Cumbria use elaborate coloured maps to compare plant distribution with physical features, a valuable advance made possible by modern printing technology.

Ten-kilometre square records of Arnoseris minima (lamb’s succory) plot the gradual decline to extinction in about 1970 of this once widespread ‘weed’. Hollow circles are records pre-1930, solid circles 1930-1970. (BSBI/CHE)

There are a growing number of ‘county faunas’, mainly of birds or butterflies, but on occasion extending to other vertebrates and at least the more popular invertebrates. Surrey Wildlife Trust has published a wonderful series of local insect ‘faunas’, including hoverflies, dragonflies, ladybirds and grasshoppers. Local bird reports have reached a high state of elaboration. They are often produced annually, enabling the present year to be compared with the last and revealing population trends. By contrast, many fine wildlife journals have fallen by the wayside, victims of rising costs and falling subscriptions, such as the long-running Scottish Naturalist and Nature in Wales. Fortunately the magazine British Wildlife came in the nick of time to rescue serious naturalists, and includes valuable news reports on all the main groups of flora and fauna. There are welcome signs of a revival in regional or specialised publications, such as Natur Cymru, the new ‘review of wildlife in Wales’, and the lively magazine Atropos, which is devoted to moths, butterflies and dragonflies.

Tetrad records of Danish scurvy-grass from A Flora of Norfolk reveal the plant’s fidelity to a natural habitat, coastal salt marshes, and its mimic, the moist, salty verges of main roads. (Alec Bull & Gillian Becket)

A series of Red Data Books has been published on rare and vulnerable species, each one containing a great deal of ecological information on the eternally fascinating question of why some species are rare. The more recent ones include distribution maps. So far there are Red Data Books for Vascular Plants (first published 1977, 3rd edition 1999), Insects (1987), Birds (1990), Other Invertebrates (1991), Stoneworts (1992), Mammals (1993), Lichens (in part – 1996) and Mosses and Liverworts (2001). There is also Scarce Plants in Britain (1993), a kind of ‘Pink Data Book’ for wild flowers that live on the edge of conservation activity. Together they cover nearly 4,000 species, and undoubtedly many more would qualify, especially if we knew more about fungi, or soil and marine life. It is a daunting thought that perhaps a quarter of our wild plants and animals are rare enough to warrant conservation action – and, if our climate is truly changing, that this proportion will rise.

Site registers and monitoring schemes

To conserve species in a site-based system of nature conservation you need to link species to places. During the 1980s, the NCC embarked on a series of grand, nationwide habitat surveys, a kind of resource account of Britain’s wildlife. Cumulatively they produced a detailed documentation of Britain’s wild places as a factual basis for conservation decisions. The NCC drew on existing, scattered information, but the surveys also amounted to possibly the most ambitious programme of field survey there has ever been. First there were the habitat surveys: ancient woodland (‘the Ancient Woodland Inventories’), the coast (‘Sand-dune Survey’, ‘Estuaries Review’), peatlands (‘National Peatland Resource Inventory’) and rivers. Beyond the shoreline there was the Marine Conservation Review (q.v.), analogous to the Nature Conservation Review on land, which classifies maritime communities and documents the best sites. The Geological Conservation Review did the same for rock strata and special geological sites over 41 volumes. Then there were the species reviews. The Invertebrate Site Register documented the best sites of insects and other invertebrates. A Rare Plant Survey did the same for rare vascular plants. The long-running Seabirds at Sea project discovered where seabirds went and what they did once they were beyond the reach of land-based binoculars. These surveys formed a mass of raw material that could be tapped for SSSI notification, species protection, drawing up oil-spill contingency plans etc. The Geological and Marine Conservation Reviews were also major contributions to pure science. Most of this work remains unpublished, perhaps destined to remain forever in sagging, spiral-bound folders thronging the shelves of conservation offices or lodged somewhere in the labyrinth of cyberspace. It is almost unsung, this last, vast outpouring of British natural history. The NCC’s successor agencies continued some of it, and implemented smaller-scale surveys of their own, though generally for a particular, short-term purpose, but none of them had any interest in praising the work of their predecessor. All the same, it was a tremendous voyage of discovery with able captains. Those of its mariners that are not retired are now mostly in administrative conservation jobs, or working as consultants.