Полная версия

The Mitfords: Letters between Six Sisters

I have shirked the Grosvenor Place party2 because I was advised it would be better not to go. They ALL cried when I wouldn’t & I gave as an excuse ‘Grosvenor Place is such a big house to surround so thought it more friendly to save half a dozen men & stay at home’.

Darling you are my one ally. But it is vastly lying to suggest you encouraged my sot [foolish] behaviour;3 you always said it would end in TEARS.

Do come here soon. I am not hurrying to leave because if Bryan leaves ME the onus is on HIM and so he will.

All love darling, Diana

Darling,

At last a moment to write you – & now my fingers are too cold to hold the pen! Oh the cold is awful, luckily the ’tectives have made themselves an awfully cosy little wigwam outside with a brazier & are keeping themselves warm & happy taking up the road. Bless them.

Saw Bryan yesterday, he was pretty spiky I thought, keeps saying of course I suppose it’s my duty to take her back & balls of that sort. Henry Yorke1 told him you had gone to Mürren with Cela.2 Would I either confirm or deny? I said I thought it very doubtful if Henry knew anything about it & that I would forward a letter to you if B cared to write one.

I may say that the Lambs3 seem to have turned nasty, apparently they told B they were nearly certain you had an affair with Randolph [Churchill] in the spring.

Lunched with Dolly [Castlerosse] & Delly.4 Delly said I don’t mind people going off & fucking but I do object to all this free love. She is heaven isn’t she?

I had a long talk with Mrs Mac5 who refuses to stay with Bryan. She says you are the one she is fond of. I told her it would mean no kitchen maid but she doesn’t seem to mind that idea at all. You must see her as soon as you get back. B & Miss Moore6 both told her (a) you couldn’t afford her & (b) you wouldn’t be entertaining at all, but living in a very very quiet retirement.

Rather wonderful old ladies in fact.7

John [Sutro] had a long talk to the Leader & is now won over. Next tease for John, ‘Why even Mosley can talk you round in half an hour’.

Best love darling, Nancy

1 Diana had just had her tonsils out and was convalescing at the seaside.

2 Patrick Cameron; a dancing partner of Nancy and Pamela, and a frequent visitor at Asthall.

3 Mary Milnes-Gaskell; a friend of Nancy from schooldays. Married Lewis Motley in 1934.

4 Oliver (Togo) Watney (1908–65). Member of the brewing family and a country neighbour of the Mitfords. He was briefly engaged to Pamela in 1929. Married Christina Nelson in 1936.

5 David Mitford, 2nd Baron Redesdale (1878–1958). The sisters’ father believed that Asthall was haunted by a poltergeist, which was one of the reasons he eventually sold the house and built Swinbrook.

1 After much wrangling with her parents, Nancy had been allowed to enrol at the Slade School of Fine Art. She had little artistic talent, received small encouragement from her teachers and left after a few months.

2 University College London, of which the Slade is a part, was the first university in England to welcome students regardless of their race, class or religion.

3 Diana was in Paris learning French and staying in lodgings where the only bath was a shallow tin of water brought to her room twice a week.

1 Unity in ‘Boudledidge’ (the first syllable pronounced as in ‘loud’), the private language invented by Jessica and Unity. This was incomprehensible except to themselves and Deborah who, although she understood it, would never have dared venture on to her older sisters’ territory and speak it.

1 A weekend cottage that Lady Redesdale had rented before the First World War when the Mitfords were living in London. After the war, she bought it and the family lived in it during the Depression while Swinbrook was let.

2 Laura Dicks (1871–1959). The daughter of a Congregationalist blacksmith who went as nanny to the Mitfords soon after Diana’s birth in 1910 and stayed until 1941. Known as ‘Blor’ or ‘M’Hinket’, she provided a steady, loving presence during the sisters’ childhood and was the model for the nanny in Nancy’s novel The Blessing (1951).

‘Blor’, the Mitfords’ much-loved nanny, Laura Dicks. c.1930.

3 In her memoirs, Jessica remembered selling her appendix to Deborah for £1 (£50 today) and that it was later disposed of by their nanny. Hons and Rebels (Victor Gollancz, 1960), p. 39.

4 Bryan Guinness, 2nd Baron Moyne (1905–92). Diana had finally overcome parental opposition and became engaged to Bryan in November 1928. He trained to be a barrister but left the Bar in 1931 when he realized that his wealth was preventing him from being given briefs. His first novel, Singing Out of Tune, was published in 1933, followed by further volumes of poetry, novels and plays. Married to Diana 1929–34, and to Elisabeth Nelson in 1936.

1 Pamela’s engagement to Oliver Watney had been broken off shortly before they were to be married. Pamela was not in love, and Togo was tubercular and probably impotent, but it was a disappointment nevertheless.

2 To help her get over her broken engagement, Pamela accompanied her parents on one of their regular visits to prospect for gold in Canada where Lord Redesdale hoped, in vain, to restore the family fortune.

1 Diana and Bryan had been lent Pool Place, a seaside house in Sussex belonging to Lord Moyne.

2 Evelyn Gardner (1903–94). Married to Evelyn Waugh in 1928. Nancy’s spell as her guest was short – lived; soon after her arrival the two Evelyns separated and later divorced.

3 Sydney Bowles (1880–1963). While they were prospecting for gold, Lady Redesdale and her husband lived in a simple cabin where she did the cooking and cleaning.

1 Lady Redesdale, whose father brought her up according the dietary laws of Moses because he believed they were healthy, forbade her own children to eat rabbit, shellfish or pig. ‘No doubt very wise in the climate of Israel before refrigeration, but hardly necessary in Oxfordshire,’ Deborah wrote in a childhood memoir, Counting My Chickens (Long Barn Books, 2001), pp. 168–9.

Pamela with Lord and Lady Redesdale at ‘the shack’, prospecting for gold in Swastika, Ontario. 1929.

1 Diana and Bryan’s London house.

2 James Alexander (Hamish) St Clair – Erskine (1909–73). Nancy’s unhappy relationship with the flighty, homosexual son of the Earl of Rosslyn was in its second year and although she considered him her fiancé, they were never officially engaged.

1 All the sisters except Nancy and Diana were on a winter holiday with their parents. The Redesdales were both keen skaters and used to take the family to the Oxford ice rink every Sunday. It was once suggested that Deborah should train for the British skating team, a proposal that Lady Redesdale immediately rejected.

2 Feodor Chaliapin (1873–1938). The great Russian operatic bass had left the Soviet Union in 1921 and was based in Paris.

1 Jonathan (Jonnycan) Guinness, 3rd Baron Moyne (1930–). Diana’s eldest son became a writer and banker. Author, with his daughter Catherine, of The House of Mitford (1984), a history of three generations of the family. Married to Ingrid Wyndham 1951–63, and to Suzanne Lisney in 1964.

1 When she was a baby, Diana’s head was thought to be too big for her body and was nicknamed ‘The Bodley Head’ by Nancy, after the publishing company of that name.

2 There is no record of what was wrong with Jessica.

3 Nancy’s first novel, Highland Fling (1931).

4 George Bowles (1877–1955). Lady Redesdale’s elder brother was manager of The Lady, the family magazine to which Nancy contributed her first articles. Married 1902–21 to Joan Penn and to Madeleine Tobin in 1922.

5 Iris Mitford (1879–1966). Lord Redesdale’s younger sister was the archetypal maiden aunt, loved by all but very censorious. General Secretary of the Officers’ Families’ Fund, she devoted her life to charitable works.

1 Dora Carrington (1893–1932). The Bloomsbury painter, a friend and neighbour of Diana at Biddesden, had shot herself with a gun that Bryan had lent her to hunt rabbits. Two months previously, Lytton Strachey, the love of Dora’s life, had died aged fifty-one.

1 The London Season opened with a ball at Buckingham Palace at which debutantes were presented to the King and Queen. Unity would have been required to walk up to the royal couple, curtsey twice and retreat backwards gracefully.

2 Thomas (Tom) Mitford (1909–45). The sisters’ only brother, nicknamed ‘Tud’ or ‘Tuddemy’ (to rhyme with ‘adultery’ because of the success his sisters believed he had with married women), was studying to be a barrister in London.

1 Tom Mitford.

2 Diana had told her family that she was planning to leave Bryan.

1 Nancy’s second novel, Christmas Pudding (1932).

2 Sir Oswald Mosley (1896–1980). Diana’s affair with the leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) had begun earlier in the year. Mosley was married to Lady Cynthia Curzon 1920–33 and to Diana in 1936.

3 Bryan was so distraught by the break-up of his marriage that he could not face the resulting upheaval in domestic arrangements. He asked Diana to pack up their London house in Cheyne Walk and find him a flat.

4 Diana had joked to Nancy that she was going to stock up on ‘a trousseau’ of expensive clothes while she could still afford them.

1 Randolph Churchill (1911–68). Winston Churchill’s only son was related to the Mitfords through his mother, Clementine. He was a great friend of Tom and had a crush on Diana as a teenager. In 1932, he began his journalistic career covering the German elections for the Sunday Graphic. Married to Pamela Digby 1939–46 and to June Osborne 1948–61.

2 Doris Delavigne (1900–42). Beautiful, uninhibited daughter of a Belgian father and English mother. Married the gossip columnist Viscount Castlerosse in 1928.

3 John Sutro (1904–85). Talented mimic, musician and film producer from a well-off Jewish London family. A lifelong friend of Nancy and Diana, he was best man at Nancy’s wedding and Jonathan Guinness’s godfather. Married Gillian Hammond in 1940.

4 Walter Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne (1880–1944). Diana’s father-in-law, a distinguished soldier and politician, was assassinated in Cairo by members of the Stern gang, a Jewish terrorist group.

5 Robert Byron (1905–41). Travel writer whose best-known book, The Road to Oxiana (1937), was a record of his journeys through Iran and Afghanistan. Nancy counted him as one of her dearest friends and mourned him for many years after his death at sea.

6 Nigel Birch (1906–81). A tart and witty friend of Tom who became a Conservative MP after the war. Married Esmé Glyn in 1950.

1 Diana’s father-in-law had hired private investigators to gather evidence that could be used in the divorce hearing.

2 A Christmas party at the Moynes’ London house.

3 The Redesdales and Tom blamed Nancy for supporting Diana’s decision to leave Bryan.

1 Henry Yorke (1905–73). Author, under the pseudonym Henry Green, of nine highly original novels, including Blindness (1926), Living (1929) and Doting (1952). Married Adelaide (Dig) Biddulph in 1929.

2 Lady Cecilia Keppel (1910–2003). A childhood friend of Diana. The Redesdales had asked her to invite their daughter to Switzerland in the hopes that removing her from Mosley would make her change her mind.

3 Henry Lamb (1883–1960). A founder member of the Camden Town Group who had painted a portrait of Diana the previous year. Married, in 1928, to Lady Pansy Pakenham (1904–99).

Diana (right) with her childhood friend Cecilia Keppel in Mürren, Switzerland, 1933.

4 Adele Astaire (1897–1981). Older sister and original dance partner of Fred Astaire with whom she starred on stage until 1932, when she married Lord Charles Cavendish, second son of the 9th Duke of Devonshire and uncle of Deborah’s future husband.

5 The cook at Biddesden.

6 Bryan Guinness’s secretary.

7 At about this time Nancy wrote a privately circulated short story, The Old Ladies, loosely based on herself and Diana. The two old ladies lived in Eaton Square and had a friend, the Old Gentleman, who was based on Mark Ogilvie-Grant.

TWO 1933–1939

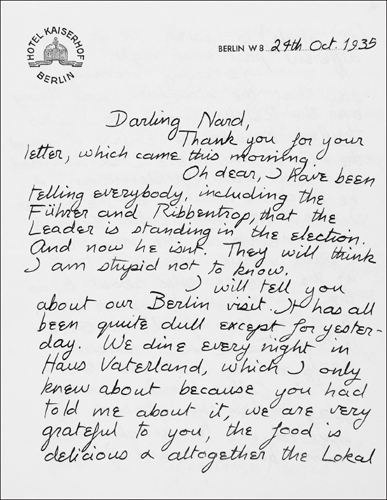

Letter from Unity to Diana.

By mid-1933, to all appearances, the three eldest Mitford sisters were settling down. At almost thirty, Nancy had at last reached the end of her affair with Hamish and was engaged to Peter Rodd, a clever, handsome banker, son of the diplomat Lord Rennell, who seemed on the surface a far better prospective husband than Hamish. Pamela was living in a cottage at Biddesden and managing the Guinness farm. Diana’s affair with Oswald Mosley was still regarded with disapproval by her parents, but her divorce from Bryan and the sudden death of Mosley’s wife had weakened the Redesdales’ opposition. The three youngest Mitfords were giving no outward cause for worry. Unity had become a keen member of the British Union of Fascists but this had been kept secret from her parents and they had no reason to suspect her growing fanaticism. Jessica, who was going to Paris for a year to learn French, was about to have her first taste of longed-for freedom. Thirteen-year-old Deborah was content in the Swinbrook schoolroom.

But beneath the deceptively calm surface, personal choices and political events combined to make the years leading up to the war a period of turmoil in the sisters’ lives. Nancy had accepted Peter’s proposal of marriage on the rebound, just a week after Hamish, desperate to extricate himself from their sham engagement, had pretended to be engaged to another woman. Peter, or ‘Prod’ as he soon became known in the family, was no more in love with Nancy than Hamish had been, but, like her, he was nearing thirty and was under pressure from his parents to marry. Peter’s career before meeting Nancy was as inglorious as his record after their marriage: he had been sent down from Oxford and was then sacked or had resigned from a succession of jobs, mostly found for him by his father. He was not only a drinker and a spendthrift, but pedantic and arrogant to boot. For Nancy, however, his proposal came as balm after the humiliation of being jilted by Hamish and she remained blind to his shortcomings. They were married at the end of 1933 and settled in Rose Cottage, a small house near Chiswick, where Nancy, in love with being in love, played for a while at being happy, writing to a friend, with no apparent irony, that she had found ‘a feeling of shelter & security hitherto untasted’. Since Pamela’s engagement to Oliver Watney had been called off, Nancy was now the only married Mitford – a not unimportant consideration as the eldest daughter. It was not long, however, before her determination to be amused by Peter’s inadequacies began to falter and her ability to overlook his unfaithfulness, neglect and over – spending was severely tested. In 1936, they moved into London, to Blomfield Road in Maida Vale, which suited Nancy because it brought her closer to her friends. But with no children – she suffered a miscarriage in 1938 – her marriage was increasingly unhappy.

Nancy could never take politics very seriously. Peter had left-wing leanings and she too became a socialist for a while, ‘synthetic cochineal’ according to Diana. When they returned from their honeymoon Peter and Nancy went to several BUF rallies, bought black shirts and subscribed to the movement for a few months. In June 1934 they even attended Mosley’s huge meeting at Olympia, which must have led Diana to hope that another sister was being won round to the cause. But Nancy was beginning to find Unity and Diana’s fanaticism distasteful. It was not just their political opinions that she disliked, she also deplored the seriousness with which they defended them. The posturing and self-importance that accompanied extremism went against her philosophy that nothing in life should be taken too seriously. Characteristically, she responded with mockery and wrote Wigs on the Green, a novel that satirized Mosley, fascism and Unity’s blind enthusiasm. Its publication in 1935 angered Diana: Mosley and his movement were one area where jokes were unacceptable and she regarded any attack on him as an act of betrayal. She broke off relations with Nancy and the two sisters hardly saw or wrote to each other until the outbreak of war four years later. Unity also threatened never to speak to Nancy again if she went ahead with publication but failed to put her threat into action. Nancy’s letters to Unity, written in the same mocking tone that she used in her novel, betrayed an underlying affection for her wayward younger sister in spite of her aversion to her politics.

Pamela ran the Biddesden dairy farm until the end of 1934. After her broken engagement she had many suitors but formed no deep emotional attachments. John Betjeman, the future poet laureate, proposed to her twice but, although fond of him, she was not in love and turned him down. Her hobby was motoring; she was a tireless driver and made several visits to the Continent in her open-topped car, travelling as far as the Carpathians in Eastern Europe. In 1935, Derek Jackson, a brilliant physicist with a passion for horses, who worked at the Clarendon Laboratory in Oxford and hunted with the Heythrop hounds in the Cotswolds, began to court her. He had known the Mitfords for some years and, according to Diana, was in love with most of them, including Tom. Pamela was the sister most readily available and he proposed to her. Fifteen – year – old Deborah, who had a crush on Derek, fainted when she heard the news. Pamela and Derek were married at the end of 1936 and set off for Vienna for their honeymoon. On arrival, they were greeted with the news that Derek’s identical twin, Vivian, also a gifted physicist, had been killed in a sleigh-riding accident. Part of Derek died with his brother, who meant more to him than anyone – including Pamela – ever could. Derek’s speciality, spectroscopy, the study of electromagnetic radiation, was, unsurprisingly, a closed book to Pamela and she did not share his interest in painting and literature. Their joint passion was for their four long-haired dachshunds and the dogs may have gone some way towards making up for the children Derek did not want and which Pamela never had. Derek had inherited a large fortune from shares in the News of the World and was a generous man. They settled at Rignell House, not far from Swinbrook, where Pamela’s housekeeping talents made them very comfortable. Pamela’s few letters that survive from this period are written to Jessica, after Jessica’s elopement with Esmond Romilly, and to Diana to thank her for visits to Wootton Lodge, the house in Staffordshire that the Mosleys rented between 1936 and 1939. Derek got on well with Mosley and shared many of his political opinions. Nancy attended Pamela’s wedding but saw little of her until after the war; she did not like Derek and he in turn resented her treatment of Pamela.

In May 1933, Mosley’s 34-year-old wife, Cynthia, died from peritonitis, a month before Diana was granted a divorce from Bryan. Diana records that both she and Mosley were shattered by Cimmie’s unexpected death. Mosley threw himself into building up the BUF, which was growing increasingly militaristic and disreputable in the eyes of the general public, and embarked on an affair with Alexandra (Baba), Metcalfe, his wife’s younger sister. That summer, while the man for whom she had sacrificed so much was on holiday with another woman, Diana received an invitation to visit Germany from Putzi Hanfstaengl, Hitler’s Foreign Press Secretary, whom she met at a party in London. The British press had been criticizing the Nazis’ attacks on the Jews, and the BUF’s anti-Semitic stance was bringing it into conflict with British Jewry. When Diana questioned Hanfstaengl about the German regime’s attitude to Jews, he issued a challenge: ‘You must see with your own eyes what lies are being told about us in your newspapers’. In August, while her two sons – Jonathan was now three and a half and Desmond nearly two – were spending the holidays with Bryan, Diana left for Germany, taking with her nineteen-year-old Unity whose allegiance to Mosley made her a natural ally. Hitler had been elected Chancellor at the beginning of the year and the sisters’ arrival coincided with the annual Nuremberg Party Congress, a four-day celebration of the Nazis’ accession to power. The gigantic parades impressed Diana and demonstrated that fascism could restore a country’s faith in itself. Although Hanfstaengl’s promise of an introduction to Hitler did not materialize on this visit, she saw that links with Germany could be useful for furthering the interests of Mosley, whose career and welfare had now become the centre of her existence. At the end of 1934, with Mosley’s encouragement, she returned to Munich for a few weeks to learn German.

Unity had been in Germany since the spring of that year. She too had been enthralled by the Parteitag parades and her burning ambition was now to meet Hitler, whom she considered ‘the greatest man of all time’. Confident that she would succeed, she persuaded the Redesdales to allow her to live in Munich, where she set herself to learn German so as to be able to understand the Führer when they eventually met. From then until the outbreak of war, Unity lived mostly in Germany. Heedless of the inhumanity of the regime, she embraced the Nazi creed unquestioningly and let it take over her life. Hitler became her god and National Socialism, as she wrote exultantly to a cousin, ‘my religion, not merely my political party’. When she discovered that the Führer often lunched informally at the Osteria Bavaria, a small local restaurant, she started going there daily, sitting at a table where he could see her, and waited to be noticed. In February 1935, her patience was rewarded when Hitler invited her over to his table, spoke to her for half an hour and paid for her lunch. Over the next five years she was to see him more than a hundred times. She was rarely alone with him and, in spite of what has often been speculated, there was no love affair. Just to be in her idol’s orbit was sufficiently intoxicating and gave Unity a sense of importance which led her to imagine that she had a role to play in Anglo-German relations.

Unity spent her first months in Munich lodging with Baroness Laroche, an elderly lady who ran a finishing school for young English girls; she then lodged in a students’ hostel and a succession of flats before moving, in June 1939, into accommodation in Agnesstrasse found for her by Hitler and belonging, she wrote insouciantly to Diana, ‘to a young Jewish couple who are going abroad’. All the other members of the Mitford family, except Nancy, eventually made their way out to Germany. The Redesdales, who had initially disapproved of Nazism, were eventually won round to Unity’s point of view – permanently so in the case of Lady Redesdale.

Diana also met Hitler for the first time in the spring of 1935 and she remained loyal to their friendship for the rest of her life. In her view, the Second World War and its horrific consequences could have been avoided. Of all the sisters, the contradictions in Diana’s character are perhaps the most difficult to reconcile. The latent anti-Semitism and racism of pre-war Britain, assumptions that she never questioned, were at odds with her innately empathetic nature. Her admiration for a barbaric regime, whose essential characteristic was dehumanizing its opponents, jarred with the qualities of generosity and tolerance that led her family and many friends to cherish her. Endowed with originality and intelligence, and priding herself on intellectual honesty, she never acknowledged the reality of Hitler’s criminal aims. While her pre-war sympathy with Nazism can be accounted for by her witnessing the economic transformation of Germany under National Socialism, Diana’s post-war defence of Hitler can be mainly explained by her devotion and undeviating commitment to her husband. Mosley’s links with the Nazis and his opposition to the war brought his political career to an end and led to his and Diana’s imprisonment for three and a half years – years of social ostracism and public vilification during which they were separated from their young children. Diana, who possessed all the Mitford obduracy, sacrificed so much for Mosley that forever afterwards she had to go on defending his cause or admit that the losses and privations she had suffered were for no purpose.