Полная версия

The Mitfords: Letters between Six Sisters

THE MITFORDS

Letters Between Six Sisters

EDITED BY

CHARLOTTE MOSLEY

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

INDEX OF NICKNAMES

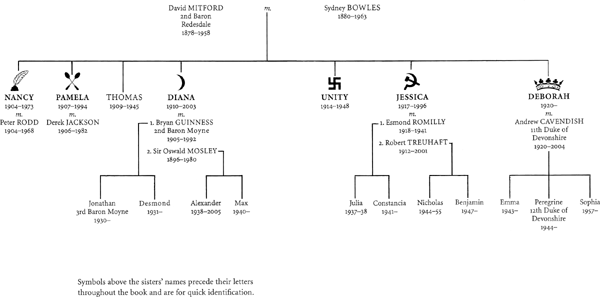

THE MITFORD FAMILY TREE

EDITOR’S NOTE

INTRODUCTION

ONE · 1925–1933

TWO · 1933–1939

THREE · 1939–1945

FOUR · 1945–1949

FIVE · 1950–1959

PLATES

SIX · 1960–1966

SEVEN · 1967–1973

EIGHT · 1974–1994

NINE · 1995–2003

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Married to Peter Rodd, 1933–58. No children. Studied briefly at the Slade School of Art before embarking on a writing career with Vogue and The Lady. Worked in London at Heywood Hill bookshop during the war. Fell in love with Free French officer Gaston Palewski in 1942, moved to Paris in 1946 to be near him and remained in France, an ardent Francophile, for the rest of her life. Flirted with socialism and fascism before becoming a staunch Gaullist after meeting Palewski. Achieved fame with her post-war novels and repeated the success with four historical biographies. Author of the novels Highland Fling (1931), Christmas Pudding (1932), Wigs on the Green (1935), Pigeon Pie (1940), The Pursuit of Love (1945), Love in a Cold Climate (1949), The Blessing (1951) and Don’t Tell Alfred (1960), and of the historical biographies Madame de Pompadour (1954), Voltaire in Love (1957), The Sun King (1966) and Frederick the Great (1970). Editor of a collection of letters of nineteenth-century Mitford cousins, The Ladies of Alderley (1938) and The Stanleys of Alderley (1939), and of a volume of essays and journalism, The Water Beetle (1962). Her notorious article on ‘U and Non-U’ (upper-and non-upper-class usage) in Encounter magazine (1954) was reprinted in Noblesse Oblige (1956).

Down-to-earth in her tastes and interests, she was a superb cook and happiest living in the country in the company of her dogs. From 1930 to 1934, she managed the farm at Biddesden in Wiltshire for Diana’s first husband, Bryan Guinness. Married to physicist Professor Derek Jackson, 1936–51. No children. When married, she lived at Rignell House, Oxford, before moving to Tullamaine Castle, Ireland, in 1947. In 1963, she settled in Zurich and shared her life with two women, Giuditta Tommasi and Rudi von Simolin. Returned to England in the mid-1970s to live at Woodfield House in Gloucestershire, which she had bought in 1960. She became an acknowledged expert on rearing poultry. Entertained the idea of writing a cookbook but never found time to finish it.

The acknowledged beauty of the family. Married to Bryan Guinness, 2nd Baron Moyne, 1929–34. Two sons, Jonathan and Desmond. Married fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley in 1936. Two sons, Alexander and Max. A visit to the 1933 Nuremberg Nazi Party Rally ignited a lifelong admiration for Hitler. Imprisoned in Holloway in 1940 under Defence Regulation 18B. Released in 1943, reunited with her children, and held under house arrest until the end of the war. Moved to Ireland in 1951 and lived between Co. Galway, Co. Cork and France. Settled permanently outside Paris in 1963. Until Mosley’s death in 1980, she devoted herself to the furtherance of his comfort and happiness. Edited and contributed to The European, 1953–60, a monthly magazine to advance Mosley’s ideas of a united Europe. Reviewed for Books & Bookmen and the Evening Standard. Author of an autobiography, A Life of Contrasts (1977), pen portraits of friends, Loved Ones (1985), and a biography, The Duchess of Windsor (1980).

Artistic, rebellious and keen to shock, she became a supporter of the Nazis after attending the Nuremburg Parteitag with Diana in 1933. Moved to Munich in 1934. Met Hitler in February 1935 and continued to see him frequently until the outbreak of war. Attempted to commit suicide in 1939 when war was declared between England and Germany. She lived on as an invalid, cared for by her mother, until her death aged thirty-three.

Became a socialist in her teens and eloped, aged nineteen, to civil-war-torn Spain to marry her cousin Esmond Romilly. Moved to America in 1939. Esmond joined the Canadian Air Force and was killed in 1941. Two daughters, Julia (died at five months) and Constancia (‘Dinky’). Married American attorney Robert Treuhaft in 1943. Two sons, Nicholas (died aged ten) and Benjamin. Active member of the American Communist Party, 1944–58, and energetic campaigner for civil rights. The success of her autobiography, Hons and Rebels (1960), enabled her to make a living from writing. Prolific investigative journalist and author of Lifeitselfmanship (1956), The American Way of Death (1963), The Trial of Dr Spock (1969), Kind and Usual Punishment (1973), a second volume of memoirs, A Fine Old Conflict (1977), The Making of a Muckraker (1979), Faces of Philip, A Memoir of Philip Toynbee (1984), Grace Had an English Heart (1988) and The American Way of Birth (1992).

Married, in 1941, Lord Andrew Cavendish, who succeeded his father as 11th Duke of Devonshire in 1950. One son, Peregrine, two daughters, Emma and Sophia. Immunized by her sisters’ fanatical views, she remained firmly apolitical all her life. An astute and capable businesswoman, she was largely responsible for putting Chatsworth, the Devonshire family home, on to a sound footing after she and her husband moved back into the house in 1959. Accused by Nancy of illiteracy, she was suspected by her family and friends of being a secret reader. Diana believed that unlike most people who pretend to have read books that they have not, Deborah pretended not to have read books that she had. She took to writing late in life and produced The House: A Portrait of Chatsworth (1982), The Estate, A View of Chatsworth (1990), Farm Animals (1991), Treasures of Chatsworth (1991), The Garden at Chatsworth (1999), Counting My Chickens (2001), The Duchess of Devonshire’s Chatsworth Cookery Book (2003) and Round About Chatsworth (2005).

INDEX OF NICKNAMES

Al Alexander Mosley, Diana’s son Bird/Birdie Unity Blor Laura Dicks, the Mitfords’ nanny Bobo Unity Boud/y Unity Cake Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother Cha Charlotte Mosley, Diana’s daughter-in-law and editor of these letters Colonel, Col Gaston Palewski Cord Diana Count/y Jean de Baglion Cuddum Communist Deacon Elizabeth Cavendish, Deborah’s sister-in-law Debo Deborah Decca Jessica Diddy Ellen Stephens, the Devonshires’ nanny Dink/y/Donk Constancia Romilly, Jessica’s daughter Duch (my) Mary, Duchess of Devonshire, Deborah’s mother-in-law Em Emma Tennant, née Cavendish, Deborah’s elder daughter Farve Lord Redesdale Fat Friend (F. F.) President John F. Kennedy Fem Lady Redesdale French Lady Nancy Hen/Henderson Deborah or Jessica Honks Diana Id/Idden Ann Farrer, a first cousin of the Mitfords Jonnycan Jonathan Guinness, Diana’s eldest son Kit Oswald Mosley Lady Nancy Leader/Lead Oswald Mosley Little gurl Sophia Cavendish, Deborah’s younger daughter Loved One President John F. Kennedy Maggot Margaret Ogilvy Mrs Ham Violet Hammersley Muv Lady Redesdale Nard/y Diana Naunce/Naunceling Nancy Oys James and Chaka Forman, Jessica’s grandsons P’s/Parent Birds Lord and Lady Redesdale Prod Peter Rodd, Nancy’s husband Recs Chickens Revereds Lord and Lady Redesdale Rud/Rudbin Joan Farrer, a first cousin of the Mitfords Sir O Oswald Mosley Squalor Jessica Sto/Stoker Peregrine Hartington, Deborah’s son Tig Anne Tree, née Cavendish, Deborah’s sister-in-law TPOF Lady Redesdale, ‘The Poor Old Female’ Tud/Tuddemy Tom Mitford Uncle Harold Harold Macmillan Wid/Widow Violet Hammersley Wife Lady Mersey Woman/Woo/Wooms PamelaTHE MITFORD FAMILY TREE

EDITOR’S NOTE

The correspondence between the six Mitford sisters consists of some twelve thousand letters – over four million words – of which little more than five per cent has been included in this volume. Out of the fifteen possible patterns of exchange between the sisters, there are only three gaps: no letters between Unity and Pamela have survived, and there are none from Unity to Deborah. The proportion of existing letters from each sister varies greatly: political differences led Jessica to destroy all but one of Diana’s letters to her, while the exchange between Deborah and Diana, the two longest-lived sisters, runs to some three thousand on each side.

The Mitfords had a brother, Tom, who was sent away to school aged eight while his sisters were taught at home. Although he composed many dutiful letters to his parents, Tom rarely wrote to the rest of the family. Unlike his sisters, for whom writing was as natural as speaking, he took no pleasure in the art of corresponding. (In 1937, in a brief note added to the bottom of one of Unity’s letters to Jessica, he deplored his ‘constitutional hatred’ for letter-writing.) Perhaps his later training as a barrister also made him wary of committing his thoughts to paper. Nancy often wrote to Tom before she married and although over a hundred of her letters to him have been preserved, as have a handful from his other sisters, the correspondence is so one-sided that no letters to or from Tom have been included in this volume.

Letters make a fragmentary biography at best and I have not attempted to present a comprehensive picture of the Mitfords’ lives; those seeking a more complete account can turn to the plentiful books by and about the family. In order to weave a coherent narrative out of the vast archive and link the six voices, I have focused my choice of letters on the relationship between the sisters. I have also selected striking, interesting or entertaining passages, as well as those that are particularly relevant to the story of their lives. While some letters have been included in their entirety, more often I have deliberately cut them, sometimes removing just a sentence, at other times paring them down to a single paragraph. To indicate all these cuts would be too distracting and they have therefore been made silently.

As in many families, the Mitfords used a plethora of nicknames and often several different ones for the same person. While the origins of most of these are long forgotten, the roots of a few can be traced. Sir Oswald Mosley, Diana’s husband of forty-four years, who was known as ‘Tom’ or ‘the Leader’ before the war and ‘Sir O’, ‘Sir Oz’ or ‘Sir Ogre’ after the war, was nearly always called ‘Kit’ by Diana. In private she admitted that the name came from ‘kitten’ but, realizing its inappropriateness for such a powerful character, she wrote in her memoirs that she could not remember how it had originated. Deborah knew him as ‘Cyril’ because as a young girl she had asked her mother how she should address her new brother-in-law and misheard her terse answer, ‘He’S Sir Oswald to me’. Nancy often referred to Mosley as ‘Keats’, a derivation of ‘Kit’. Deborah’S husband, Andrew Devonshire, was known as ‘Ivan’ (the Terrible) or ‘Peter’ (the Great), according to his mood. He was also called ‘Claud’ because when his title was Lord Harrington, before he inherited the dukedom, he used to receive letters addressed to ‘Claud Hartington Esq.’ To make matters even more complicated, Nancy and Jessica addressed and signed letters to each other as ‘Susan’ or ‘Soo’, for reasons now forgotten; Deborah and Jessica called each other ‘Hen’, and by extension ‘Henderson’, inspired by their passion for chickens; Jessica and Unity were to each other ‘Boud’, from a private language they invented as children called ‘Boudledidge’. Nancy addressed Deborah as ‘9’, the mental age beyond which she claimed her youngest sister had never progressed.

I have left unchanged the sisters’ numerous nicknames for one another as they are intrinsic to their relationships, but for clarity I have standardized other nicknames and regularized their spelling. The only other editorial changes that have been made to the text are the silent correction of spelling mistakes – except in childhood letters; the addition of punctuation where necessary; and the rectification of names of people, places and books. In my footnotes and section introductions, I have referred to people variously by their first name, surname or title, aiming for quick recognition rather than consistency. Foreign words or phrases have been translated in square brackets in the text; the translation of longer sentences has been put in a footnote.

As a child, Nancy invented a game in which she played a ‘Czechish lady doctor’ and adopted a thick foreign accent. This voice endured and the letters are scattered with ‘wondair’ for ‘wonderful’, ‘nevair’ for ‘never mind’, and other phonetic approximations of Mitteleuropean English. After Nancy moved to France, should she ever use a French word in conversation, Deborah, who did not admit to speaking the language, would interject with ‘Ah oui!’ or ‘Quelle horrible surprise’, expressions that have found their way into the letters. Deborah was also the instigator of the frequent plea ‘do admit’ – not something any Mitford did willingly – which was an attempt to catch the attention of one of her siblings and get them to agree with her. The exaggerated style of writing that the sisters used, a continuation of the drawling way in which they spoke, began in childhood and originated in part from their brother Tom’s ‘artful scheme of happiness’, a particular tone of voice that he employed when trying to wheedle something out of someone. ‘Boudledidge’, which Jessica and Unity often used in their letters to each other, was a derivation of this way of speaking. ‘Honnish’, a language invented by Jessica and Deborah, was derived not from the fact that as daughters of a peer they were Honourables but from the hens that played such an important part in their upbringing. Their mother, Lady Redesdale, had a chicken farm from whose slim profits she paid for the children’s governess and the sisters each kept their own birds and sold their eggs to their mother in order to supplement their pocket money.

The Mitford sisters all wrote in longhand, except for Jessica who learned to type at the beginning of the war. Their handwriting is clear and legible, and, as a rule, they dated their letters. Pamela, who was probably dyslexic, kept a dictionary at hand and her spelling is usually accurate. Her occasional use of unorthodox capitalizations and spelling has been retained. The sisters’ letters to each other are held in the archives at Chatsworth, where they have been collected by Deborah, with the exception of those written to Jessica which are in the Rare Books and Manuscripts Library at Ohio State University. The letters in this volume are previously unpublished, except for a dozen that were included in Love from Nancy and three times that number in Decca.1

At a certain point, the sisters became aware of the value of their letters and of the possibility that they might one day be published. In 1963, Nancy advised Deborah to throw nothing away because the correspondence of a whole family would be ‘gold for your heirs’. Pamela, who until then had discarded most of her letters, began to preserve them, and Jessica started keeping carbon copies of her correspondence in the 1950s. It is nevertheless abundantly clear that the sisters did not write with an eye to posterity; the frankness, immediacy and informal style of their communications bear this out. Only when I had begun editing these letters did the idea of publication at times inhibit the two surviving sisters. A few months before she died in 2003, Diana wrote to Deborah, ‘I’ve started this letter and for the first time in my life I can’t think of anything to say. My old mind is a blank. If this had happened sooner it would have saved Charlotte a lot of trouble.’ Happily, it did not.