Полная версия

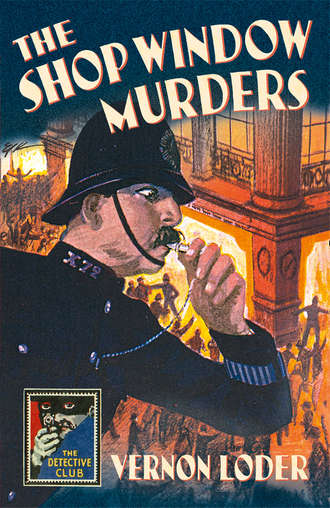

The Shop Window Murders

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by The Detective Story Club Ltd 2018

First published in Great Britain by

W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1930

Introduction © Nigel Moss 2018

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1930, 2018

Vernon Loder asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008282981

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008282998

Version: 2018-08-24

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Keep Reading …

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

VERNON LODER was a popular and prolific author of Golden Age detective mysteries and spy thrillers. He wrote 22 titles during the decade from 1928 to 1938. Subsequently Loder has been out of print and largely overlooked. Fortunately, the tide is turning. In 2013/14, two noted crime fiction commentators, Curtis Evans and J. F. Norris, championed a number of early Loder titles, the latter in a series of enthusiastic reviews. A flurry of e-reader versions of Loder stories followed. But it was not until 2016 that Loder made his first return in print since the 1930s with the re-issue of his first novel The Mystery at Stowe (1928) as part of the Collins Detective Story Club reprint series. In the original Preface, the Club’s Editor, F. T. (Fred) Smith had welcomed Loder as ‘one of the most promising recruits to the ranks of detective story writers’.

The Shop Window Murders (1930) was Loder’s fourth novel, after The Mystery at Stowe (1928), Whose Hand? (1929) and The Vase Mystery (1929). It was published by Collins in the UK, and with the same title by Morrow in the USA. The storyline is intriguing and unusual, with one of Loder’s more ingenious plots. The setting is Mander’s Department Store in London’s West End (loosely modelled on Selfridges in Oxford Street), owned by Tobias Mander and famous for its elaborate window displays. Early on a Monday morning, the crowds of passers-by pause to watch the window blinds being raised on a new weekly display, but the onlookers quickly realise that one of the wax figures is in fact a human corpse, shot and placed among the mannequins in the window display. Shortly afterwards a second victim is discovered, and this striking tableau begins a baffling and complex mystery tale. Was it murder and suicide, or double murder?

Loder draws a wide cast of diverse suspects, each with a motive for the killings. To a toxic mix of jealousy, fear, panic and anger, he adds further colour to the story with a proliferation of bizarre circumstances and enigmatic clues, displaying some fiendishly intricate plotting.

The case raises a fundamental question: why did the perpetrator of the killings leave so many signs and clues? Did it show a confused mind? Or was this a deliberate and clever attempt to confuse the police by leaving a trail of red herrings and different angles which implicated more and more characters and made proof of guilt harder to determine?

The police investigation is led by Inspector Devenish of Scotland Yard, who makes his sole appearance in Loder’s canon of detective novels. Devenish is intelligent, workmanlike, tenacious and indefatigable. He displays a strong moral compass, giving short shrift to those who lie when questioned, particularly a suspected blackmailer. He remains firmly in charge throughout, pursuing the case with impressive diligence and total absorption; though his superior powers of ratiocination are largely by dint of effort. In these qualities, Devenish perhaps resembles Freeman Wills Crofts’ famous series detective, Inspector French. He does not have any of the eccentricities which Loder bestows on some of his other police detectives: for example the likeable Superintendent Cobham in Whose Hand? (1929), who deliberately lulls suspects into a false sense of security by pretending to be an absent-minded blunderer (similar to the TV detective Columbo), and who often hums while investigating, alternating between opera arias and music hall tunes. Loder describes Devenish as ‘tall and thin, dark hair, dark eyes, and a swarthy complexion; he might have passed as a southern Italian’. Beyond this, we learn nothing of Devenish’s background or personal life, not even his first name. There is no amateur sleuth on hand to rival or potentially embarrass the police. Devenish works alone, assisted by Detective-Sergeant Davis and reports to Mr Melis, an Assistant-Commissioner. Melis is debonair, suave and ethereal, with the air of an amateur actor. But his ideas on the case often turn out to be perceptive and seminal, providing the germ from which Devenish produces workable theories.

The denouement is surprising, and not easily foreseen. But it is plausible and makes sense, even though partly speculative. It shows the plot to have been solidly clued for the reader who can follow the hints. Loder often shows villains falling prey to their own scheming and he does so again here. There is also a pervading sense of tragedy, almost tragi-comedy, affecting those directly involved. One of the killings involves a variation of a method of dispatch seen in other Loder novels. The other foreshadows the murder setting in Drop to his Death (1939), co-authored by John Dickson Carr (writing as Carter Dickson) and John Rhode.

The Shop Window Murders is an entertaining and richly plotted example of the Golden Age deductive puzzle novel. The unusual and bizarre crimes make it one of Vernon Loder’s best mysteries for bafflement and ingenuity. The narrative is direct, brisk and lively, and the complex storyline is absorbing, well-constructed and moves at a swift pace. Loder pays close attention to carefully worked-out and intricately structured plotting. But his skill in creating clever, insightful ‘good lightning sketches’ of characters, a feat praised by Dorothy L. Sayers in her review of Murder from Three Angles (1934), is also evident—Melis being a good example. The combination of subtle witty observations and good humour help to leaven an otherwise dark tale. Here is Loder describing Mander’s older female admirer: ‘She did not look an amorous type, though she was obviously endeavouring to hold her fugitive youth by the skirts’. Overall, the novel shows Loder writing with assurance and maturity as a crime fiction author.

Of particular interest to Golden Age aficionados will be the striking similarities between The Shop Window Murders and The French Powder Mystery by Ellery Queen, also published in the US and UK in 1930. It was only the second Ellery Queen Mystery, a year after the successful debut of The Roman Hat Mystery. The book begins almost immediately with a murder: a model inside the main shopfront window of French’s Department Store in downtown New York City is demonstrating some modern furniture and accessories on display, with a crowd watching from outside. When a button is pushed to reveal a concealed wall folding bed, out tumbles the murdered body of the wife of the store owner. The similarities continue: the owner has a private apartment above the store which the victim visits late one night when the store is closed. There are bizarre and unexplained clues, strange discoveries of unusual items found where they should not be, and a plethora of alibis and motives. The plot is ingenious, almost to the point of being overly complicated and involuted. Each small fact and clue is examined, discussed and (mostly) discarded with impressive deductive logic and reasoning. The rigorous intellectual approach is indebted to the popular Philo Vance mysteries of S. S. Van Dine. The climax is generously praised by the eminent critic Anthony Boucher as ‘probably the most admirably constructed denouement in the history of the detective story’. Following the trademark Queen ‘challenge to the reader’, it comprises 35 pages of tightly worded explanation, with the identity of the murderer only revealed in the last two words of the novel. Ellery Queen was the nom-de-plume of Fred Dannay and Manfred Lee, two cousins from Brooklyn. According to their biographer Francis M. Nevins, the novel was inspired after one of the cousins passed a Manhattan department store display window and stopped to look at an exhibit of contemporary apartment furnishings which included a Murphy bed. It is not possible to say whether Loder or Queen first conceived the idea of the store window murder, but the similarities between the two stories and close proximity of publication dates are certainly a remarkable coincidence.

Vernon Loder was one of several pseudonyms used by the hugely versatile and productive Anglo-Irish author Jack Vahey (John George Hazlette Vahey), 1881–1938. In addition to the canon of Loder titles between 1928 and 1938, Vahey wrote initially as John Haslette from 1909 to 1916, resuming writing in the 1920s as Anthony Lang, George Varney, John Mowbray, Walter Proudfoot and Henrietta Clandon. Born in Belfast, John Vahey was educated in Ulster and for a while in Hanover, Germany. He began his working life as an architect’s pupil, but after four years switched careers and sat professional examinations with a view to becoming a chartered accountant. However, this too was abandoned after Vahey took up writing fiction. He married Gertrude Crewe and settled in the English south coast town of Bournemouth. His writing career was cut short by his death at the relatively young age of 57.

The Loder novels were all published by Collins in the UK, and from 1930 his detective works were published under their famous Crime Club imprint. Several of his early novels (between 1929 and 1931) were also published in the US by Morrow, sometimes with different titles. The publisher’s biographical note on Loder, which appears in Two Dead (1934), mentions that his initial attempt at writing a novel (apparently never published) was during a period of convalescence in bed. Various colourful claims are made of Loder: he once wrote a novel on a boarding-house table in twenty days, serialised in both England and the US under different names; he worked very quickly, and thought two hours in the morning quite enough for anyone; also, he composed directly on a typewriter, and did not ever re-write. Whether these claims are true—or indeed laudable—is a matter for conjecture.

Loder had several recurring detectives. Inspector Brews and Chief Inspector Chace were each quite contrasting characters, the former a stolid local policeman with an emphasis on the importance of routine, the latter a highly efficient new breed of Scotland Yard CID detective. Brews appears in The Essex Murders (1930) and Death of an Editor (1931); Chace is found in Murder from Three Angles (1934) and Death at the Horse Show (1935). In his later espionage thrillers—Ship of Secrets (1936), The Men with the Double Faces (1937) and The Wolf in the Fold (1938), published under the separate Collins Mystery imprint—Loder’s protagonist was Donald Cairn, a British secret service agent involved in a series of thrilling adventures combatting continental spies in the lead-up to the outbreak of World War 2.

Loder never quite achieved the first rank of detective novelists, and has received scant attention in commentaries of the genre. Nonetheless, he was a popular, dependable author in the 1930s, and better than many; perhaps a paradigm of the English Golden Age mystery writer. The original Collins dust wrappers show that he was warmly reviewed: ‘The name of Mr Loder must be widely known as a reliable and promising indication on the cover of a detective story’ (Times Literary Supplement); ‘Successive books by Vernon Loder confirm the impression gathered by this reviewer that we have no better writer of thrill mystery in England’ (Sunday Mercury); ‘… just the effortless telling of a good story and meticulous observation of the rules’ (Torquemada in the Observer). And in 2014, J. F. Norris wrote: ‘… keep your eyes out for any book with the Vernon Loder pseudonym on the cover. They make for fascinating reading and are as different from the standard whodunits of his colleagues as champagne is to soda water.’

Since the 1930s Loder has remained out of print, and his works have largely been the purview of Golden Age book collectors, among whom he has a following, with scarce first editions commanding high prices. This welcome re-issue of The Shop Window Murders and earlier The Mystery at Stowe, should help Loder, deservedly, to be rediscovered and enjoyed by a new wider readership.

NIGEL MOSS

March 2018

CHAPTER I

MR TOBIAS MANDER’S new stores in Gaffikin Street had been a public wonder from start to finish. From the moment that this almost unknown man from the west country had visualised the idea of a store that would beat all other stores for cheapness combined with luxury, a highly-paid press-agent had seen to it that the country should join vicariously in the building and equipment.

The plans had been published in the front sheets of all the prominent newspapers, and every stage of the immense building progress had been reported with diagrams, portraits of the (titled) architect, and descriptions of all the eminent firms that had contributed to the material elegancies and equipment of the famous Store-to-be.

But Mr Tobias himself had remained unphotographed and unfeatured throughout the campaign, and no one from the outside world had even guessed accurately at the manner of man he was, until the Store was opened with a flourish of trumpets, and a luxurious house-warming.

To that function everyone of importance went. People who were wont privately to sneer at trade, forgot their principles, and crowded to the show; even titled actresses (notoriously exclusive) were among the throng.

When Mr Tobias Mander first burst upon the world, the world saw him as a man who might have been a prosperous stockbroker, a genial bookmaker, or a retired Smithfield merchant. He was of medium height, with a very fresh colour, and roving blue eyes; inclined to stoutness, always dressed in trousers with a very black stripe, a morning-coat and vest, with a white slip, and a monocle that never by any chance went into his eye.

The connoisseurs among the men called him a ‘cheery bounder’, but the women’s votes were mixed. Some thought him charming, if vulgar; and others vulgar if charming; while a few, who had encountered his roving blue eyes with a twinkle in them, declared themselves fascinated.

There was one detail in which he differed from most men of his kind, and that was in the fact that he lived on the premises. To call the very luxurious flat on the top floor ‘premises’ is modestly to understate facts. But undoubtedly Mr Mander had taken up his residence within the walls of the store.

One of the stunts with which he had taken London, some months after the store opened, was a new gyroplane. No one knew the inventor’s name, but there was trouble one day when it sailed over London, and landed with the greatest precision on top of the flat roof that covered the store. ‘The Mander Hopper’ it was called, yet that particular hop was frowned on by the authorities, who were not convinced that any aeroplane was quite safe among the roofs of a city. But the necessary prosecution provided further réclame for Mander and his store, and, later, those were not lacking who said they had heard aero-engines at night, and professed to believe that the great man sometimes landed after dark on his own roof.

There was no reason, beyond out-of-date regulations, why he should not have done so, for the ‘Mander Hopper’ proved to be the gyroplane for which the world had been looking, and the department which stocked and sold the ‘Plane you fold up in a room; and land in a tennis-court’ was one of the most paying in the whole Store. The ‘Hopper’ was, as one ancient pilot said, ‘The plane that put the F in safety.’

The windows of the store were enormous, and each window was changed weekly. There you did not see wax figures disposed in solitary state, but naturally disposed in a room, with an appropriate stage-setting, so to speak. And the contents of each window were announced in the Sunday papers, so that an avid public would know where to look for a novelty when the blinds were drawn up on Monday morning.

The store did not believe in a constant, all-night electric-lit display. Mr Mander, with the turn for quaint originality which had helped him so much in booming his business, explained to a reporter (and he, in turn, to a delighted world) the reason for this.

‘It’s my house, you see,’ he told the man. ‘I make it a rule to put business out of my head when business is over. At night, and during the weekends, the Store is my Store only in name, and you do not pull up the blinds, and keep the light on, in private houses during the night.’

During the first week in November, the Sunday papers had spoken of the season of fancy-dress, and the writers had artfully proceeded from the general to the particular, and mentioned that the principal window in the chief bay of Mander’s Store would ‘feature’ the next day a marvellous selection of fancy dresses, carried out by British workers, in British materials, by British designers.

There are always in London, at any hour of the day or night, sufficient people with no visible occupation, and an intense curiosity about anything novel, to form a crowd on the pavement. At five minutes to nine, there was a line of spectators three deep before Mander’s Stores, which was continuously being added to by fresh arrivals. Many of them, it is true, were not of the class likely to wear fancy-dress, but all kept intent eyes fastened on the immense blinds that cloaked the splendours within from view.

At nine precisely, a man inside set in motion the mechanism which raised the blinds, and there was the instant ‘Oo-er!’ of vulgar appreciation, mingled with the more polite enthusiasm of the cultivated.

The floor-space inside the window was dressed as a ball-room, even to a waxen band that sat in a recess at the back. The moment portrayed was a pause between dances, and at least forty couples in the most novel costumes stood about the floor, or leaned against the walls in dégagé attitudes that were almost lifelike.

But there was an exception to the rule, and, while most of the crowd outside were in ecstasies over the originality displayed, it was left to a commoner, a little bricklayer with ginger hair, on the outskirts, to discover it.

‘Lumme!’ he said contemptuously. ‘Mebbe it’s a novelty for the likes of ’im to work, but t’ain’t what I would call novel!’

‘It’s supposed to be a motor-mechanic,’ said someone next to him.

‘Wat if it is?’ he demanded firmly. ‘Moty mechanics isn’t novel!’

The figure in blue overalls to which he referred at once drew every eye. It was not elegant or elegantly disposed, as were the others in that window. And there was something else about it that provoked a sudden shriek, and a flop, from someone in the crowd.

Most of the spectators now concentrated on giving the fainting one as little air as possible. The few who remained at the window gasped and stared, or shivered. For there is a difference between even the best wax model and the appearance of a dead man beside it.

While they shuddered and debated, the bricklayer darted across the road to a policeman and spoke to him energetically. Then, with the policeman at his heels, he hurried in through the principal door of the great stores. Someone in the meantime had removed the public nuisance, who had fainted, and the rest of the crowd surged back to see the horror.

By the time a few more people had fainted and been duly removed, those next the window saw a door panel open at the back, and the blue-coated policeman pass through it. He was followed into the ‘ballroom’ by an alarmed shopwalker, and, when they had passed through, the supererogatory figure of the bricklayer was framed in the doorway.

There was a hush outside as the constable advanced to the figure in blue overalls, reached out a long arm, and gripped its shoulder. There was a scream as the figure overbalanced and fell down, while the mask came off, and where it had been there was disclosed a face that was quite white, but had no other visible relation to wax, and bore a striking likeness to that of Mr Tobias Mander.

Then the shopwalker turned and bellowed something, and, like the safety curtain at a fire in a theatre, the blinds came down with a rush, and blotted out every trace of the tragedy from the public view.

The constable was one of those very superior policemen who have joined up since the war. He recognised Mr Mander, and he recognised the nature of the wound which had put an end to that consummate commercial impresario. He unbuttoned part of the blue overalls.

‘Gunshot wound,’ he said slowly. ‘Let’s have some more of those electrics on, and get to the telephone, and ring up our people quick as you can—Mr Mander, isn’t it?’

‘It is,’ said the horror stricken shopwalker, who looked as if he were going to be sick. ‘It’s murder, that’s what it is!’