полная версия

полная версияThe Celebrity at Home

Simon is proud of his sister Almeria, and thinks her a “splendid girl.” She lives at their place with her widowed father, eight miles inland, and only comes to Whitby when rough weather and wrecks are expected. Then every one walks up and down the pier, and hopes that a hapless barque will come drifting to their very feet. I don’t mean we actually want there to be a wreck, but if it has to be, it may as well be where one can see it. For Ariadne has a tender heart, and when Aunt Gerty put the loaf upside down on the trencher the other day, Ariadne at once kindly put it on its right end again, for a loaf upside down always betokens a wreck, and she knows all the superstitions there are.

The two piers here are so awkwardly placed that in rough weather the poor boats can’t always clear them. So it is a regular party on the pier when the South Cone is hoisted at the coastguard-station. Irene Lauderdale wears a little shawl over her head like a factory girl. It can’t blow away, she says. She has been photographed like that, with Lord Fylingdales. They say she is going to marry him, and do what Aunt Gerty refused to do.

I don’t know if they are a very united family, but certainly his sisters chaperon him most carefully, and have taken care to be great friends with Irene, so as to have an excuse for being always with her. Lord Fylingdales never gets a chance of seeing her alone. Dear Emily (Lady Fenton) and dear Louisa (Mrs. Hugh Gore) are devoted to dear Irene, and she thinks it is because she is so nice, so good form, not because she is so nasty. They perfectly loathe and detest her. I heard Lady Fenton abusing her to some one, talking in the same breath of Almeria Hermyre as “one of us.” The sisters would prefer Lord Fylingdales to marry his cousin Almeria, of course, but her get-up is simply appalling. She wears plain skirts and pea-shooter caps, and no fringe. George says she has the most uncompromising forehead he ever saw—a front candide with a vengeance! I should think she soaps it well every morning, it looks like that.

Her father is about as queer as an old family can make him. I wish some one would tell me why if you came in with the Conqueror you are generally queer, or without a chin? Why do you always marry your near relations? Do you get queerer as you go on? No one ever answers these questions. Sir Frederick Hermyre has acres of stubbly chin, true, but he takes it out in queerness. He always wears white duck trousers, like the pictures of Wellington, whom he is rather like. He says “what is the good of being a gentleman if you can’t wear a shabby coat?” and does wear it. His house at Highsam is a show house, only they don’t show it. They are too careless, and too untidy, and too mean in the shape of housekeepers. One day some Whitby tourists went over to Saltergate in a break, and strolled up his drive to look at the Jacobean Front, and met Sir Frederick, as shabby as usual; he had been working in a stone quarry he has there, I believe.

“Did you wish to see me?” he asked the front tourist politely.

“Thanks, old cock, any extra charge?” said the tourist. It was of course all the fault of those old trousers and linen coat, and I have heard that Sir Frederick was not so very angry, and stood the man a glass of beer. He is a Liberal in spite of owning land. Simon is a Conservative. Eldest sons are always different politics to their fathers. We never see the old man hardly except on these stormy pier parties, and then he stalks up and down the pier with his daughter among us all, and though he isn’t exactly rude to anybody, he never seems to hear or care to hear what anybody is saying. Blood tells. Lady Scilly has given him up in disgust long ago; he simply answered her straight as long as he could, and when he didn’t understand her, he just shook his head and grinned and turned away.

Simon stood by, looking rather like a little whipped dog. He is awfully afraid of his father, who isn’t proud of him, but of Almeria, who he says has got all the brains of the family, and ought to have been the boy.

Simon tried introducing Ariadne to Almeria, but Ariadne’s fringe proved an insuperable barrier. As for Ariadne, Almeria’s naked forehead made her feel quite shy, she said, such a double-bedded kind of forehead as that needed covering. I said, all the same, she was an idiot not to make friends with Simon’s sister, for he had obviously a great respect for the girl’s opinion. She might have plenty of sense in spite of her bald forehead and clumpers of boots! But it was no use, they stood glaring at each other like two Highland cattle, while Simon was trying to invent a mutual bond between them.

“My sister writes a little,” he said.

“Only for nothing in the Parish Magazine,” said Almeria, witheringly.

–“And goes about,” he went on, “with a hammer collecting–”

“Bedlamites and Amorites,” said I, to make them laugh.

They didn’t laugh, and Simon continued—

“And pebbling and mossing and growing sea anemones in basins.”

Then I got excited, and as Ariadne stood mum, I supported the conversation.

“And isn’t it funny to feel them claw your finger if you put it in their mouth—well, they are all mouth, aren’t they?”

“And stomach!” said Almeria, turning away politely.

Ariadne had hardly said a word, but had left the conversation to me. But any one could see that these two never could get on. Ariadne looked as she stood on the pier, plucking at bits of hair that would get loose, just like a pale butterfly caught in the rain, while Almeria stood as fast as a capstan and as stumpy. And the abominable thing was, that Almeria was not in the least rude. She was always civil, perfectly civil—but civility is the greatest preserver of distances there is if people only knew.

Simon gave her up as far as Ariadne was concerned. He stuck to Ariadne, but did not neglect other girls or any one else for her sake, and so compromise her. He has got a lot of tact. Ariadne hasn’t any, but she is gentle and easily led, and Simon is the kind of boy who is going to grow masterful, and likes a girl who gives him the chance of standing up for her and managing for her. Perhaps he is a little bit sorry for her. Not because she is so dreadfully in love with him; he isn’t conceited enough to see that, or Ariadne would have shown him long ago. He is sorry for her because she gives herself away so in so many ways, looking pretty all the time. That is important, for it is no good looking pathetic, unless you look pretty as well. He chaffs her about her fluffy hats that go all limp in the salt sea-spray, and her pretty thin shoes that let the water in, and her hair that never will stay where she wants it. She has got into the way of continually arranging herself, patting a bow here, pulling her sleeves down over her wrist, and arranging her hair. “Always at work!” he says suddenly, and Ariadne’s guilty hands go down like clockwork. It isn’t rude, the way he says it. He looks at her kindly, not cheekily. It is that kind sort of fatherly look that I like, and that makes me think he is fond of Ariadne.

She is different from Lady Scilly, whom he is beginning slightly to detest. Sometimes he looks quite glum when she is ordering him about, but he obeys. What do married women do to men to make them their slaves as they do, and yet one can see by their eyes that they don’t want to? And why are the women themselves the last to see that the servant wants to give notice and would willingly forfeit a month’s wages to be allowed to leave at once? Lady Scilly is just like a mistress who avoids going down into her own kitchen to order dinner, at a time when relations are strained, lest the cook takes the chance of giving her warning. Lady Scilly is the least bit afraid of Simon’s cooling off, and just now prefers to give him his orders from a distance.

She calls Lord Scilly “Silly-Billy,” and “my harmless, necessary husband.” He is not dangerous, and he certainly is useful, for she really could not go about alone wearing the hats she does. She has one made of a whole parrot, and a coat made of leopard skins. I like Lord Scilly. He is rather fat, and knows it. He has a hoarse sort of voice, and yet I don’t think he drinks much. Perhaps it is the open-air life that he leads among horses and dogs and grooms; at Summer Meetings and Doncaster, and so on. He is well known as a fearless rider, and risks his neck with the greatest pleasure. If I were Lady Scilly, I should much prefer him to George, though not to Simon. His chest is broader than George’s, and he is taller than Simon, but then she isn’t married to either of those. Marriage is like the rennet you put into the junket—it turns it!

He seems quite used to the kind of wife he has got. He isn’t at all anxious to change her. He hardly ever talks about her—even to me. That is manners. Even George has got that sort of manners, so that half these smart people don’t realize that my father has got a wife, or ever had one! They might, if they liked, and after all, if Mother doesn’t choose to know his friends, he cannot force her! She won’t go out with him, though she makes no difficulties about our going. She likes us to go, as it opens our eyes and gives us chances. Her business is to see that we are clean and have nice hair not to disgrace him, and we don’t, or he would soon chuck us.

Lord Scilly always insists on our being asked to the picnics and parties they give. He likes us. He takes more notice of us than she does. I think he is a very lonely man, and quite glad of a little notice and attention even from a child. He is very observant too, I don’t believe much goes past his eye. He thinks of everything from the racing point of view. Once when Lady Scilly and Ariadne were both standing on either side of Simon, receiving about an equal share of his attention, or so it seemed, Lord Scilly suddenly chuckled and said—

“I back the little ’un!”

He always talks of and to Ariadne as if she were very young indeed, and it is the surest way to rile her. She never forgave Mrs. Ptomaine a notice of hers on the dresses at some Private View or other, when she alluded to Ariadne’s frock as worn by “a very young girl.” Lord Scilly thinks a girl ought to be able to stand chaff, and is always testing her.

Ariadne had a birthday while we were at Whitby, and it fell on the day fixed for a picnic to Robin Hood’s Bay. Simon sent her a present by the first post in the morning, a fan that he had written all the way to London for, in payment of some bet or other he had invented—I suppose he did not think it right to give an unmarried girl a present without some excuse like that?—and of course Mother and Aunt Gerty and I gave her something, and even George forked out a sovereign. That was all she expected, and not even that.

However, all the way driving to the picnic, Lord Scilly kept telling her that he was going to give her something as well; I was sure he was only teasing her, for there are no shops worth mentioning in Robin Hood’s Bay, so I advised her to brace herself for a disappointment.

The moment he got to Robin Hood’s Bay, he was off by himself, and away quite ten minutes, coming back with a showy paper parcel. At lunch he gave it her with a great deal of ceremony, so that everybody was looking. It was worse than I even had thought, a hideous china mug with “A Present for a Good Girl” on it in gilt letters. Ariadne has it now, only the servants have washed off the gilt lettering, using soda as they will. The baby was christened in it. But I am anticipating.

I had my eye on her as she untied the parcel, hoping and wondering if she would stay a lady in her great disappointment? She did. She thanked him quite formally and prettily for his charming present, though I saw her lip tremble a very little. I was awfully pleased with her, and so was Simon Hermyre, for I saw he particularly noticed her behaviour. As for the Scillys, their nasty little joke fell rather flat in consequence of Ariadne’s discretion.

It was a most fearfully hot day. We all sat on the cliff in tiers, and talked about the delightful golden weather which was so oppressive and beastly that there was nothing to do but lie about and smoke. So they did. The men mopped their foreheads when they thought no one was looking, and the women used papier poudrée slyly in their handkerchiefs. Only Ariadne had none to use, and kept cool by sheer force of will. I was all right, being only a child.

Ariadne was sitting a little apart, with me, and she was writing a Poem to the sea, and she told me in a whisper as far as she had got—

“The patient world about their feetLay still, and weltered in the heat.”“What else could it do but lie still?” I said, and suddenly just then Simon got up—

“I say! I’m going to take the kids for a sail! Bring your new mug, Missy, and take your tiny sister by the hand, so that she doesn’t fall and break her nose on the cliff steps.”

After the mug incident I don’t see how anybody could have objected, or tried to prevent Ariadne from taking the advantages of being treated as a baby, and I expect that was what Simon thought. Anyhow, Ariadne got up, and went with Simon and me as bold as any lion. It is a well-known fact that Lady Scilly can’t stand the sea in small quantities like what you get in a boat, though of course she goes yachting cheerfully. None of the others were enough interested in Simon to care to move, and take any exercise in this heat. George gave her an approving little nod as she passed him.

We had a lovely sail of a whole hour’s duration. We had an old boatman wearing his whiskers stiffened with tallow, who told us he had been a smuggler, and treated Ariadne and Simon as if they were an engaged couple, out for a spree, with me thrown in for a make-weight. It came on to blow a little, and got much cooler. Ariadne lost her hat, and had to borrow a red silk handkerchief of Simon’s and tie a knot in it at all four corners and wear it so. She looked most proud and happy, as if she had on a crown, not a hat.

When Lady Scilly saw the latest thing in hats, she cried out, “Oh, my poor Ariadne!” and helped her to hide herself more or less in the waggonette going home. I didn’t know before how becoming the cap was!

CHAPTER XV

WHEN George came, he took out a family subscription to the weekly balls at the Saloon, and we go, Ariadne and I. Mother will not and Aunt Gerty may not. Mother expressly stipulates that she shall refrain from doing as she wishes in this one particular, and as Aunt Gerty is mother’s guest, she has to please her hostess. She grumbles a good deal at George’s bearishness to her, in depriving her of any source of amusement in this dull place, but as a matter of fact she is very much taken up with Mr. Bowser. He was Ariadne’s umbrella man. The Umbrella dodge came off with Aunt Gerty, and this unpoetical two became fast friends on the cliff-walk one rainy day. Mr. Bowser is a rich brewer, and very much mixed up with the politics of this place. He owns three blocks of lodging-houses on the Front. Of course Simon Hermyre’s people won’t have anything to do with him. It would be awkward if Ariadne married Simon and Bowser had previously married Ariadne’s legal aunt. If Aunt Gerty does marry Mr. Bowser, then I do think George would be justified in cutting himself off from us all. To be the brother-in-law of Mr. Bowser would be the ruin of him. Well, chay Sarah, Sarah! as George says sometimes. At any rate we have no right to interfere with Aunt Gerty trying to do the best she can for herself. She is awfully kind to us and very loyal, Mother says, and she never gets a good word from George to make her anxious to please him. Mother gives her plenty of rope in the Bowser business, on condition she doesn’t try to squeeze herself into the Saloon dancing set where George’s friends go.

The dancing at the Saloon is very poor. The balls are only an excuse for going out on the Parade and watching the sea with a man. I like to watch it best myself, without a man. I like to see the whole dark sheet of water far away, and the thin white line near by that is all there is to tell one where the little waves are lying flattened out on the shore. The tide slips in so softly, minding its own business through the long evening while the idiots above galumph about and dance polkas in the great hall inside, with flags from the Crimea on the walls that flap in the draught of the North wind, and remind us constantly that we are hung over the sea.

There is a nice boy I like—he is twelve, quite young, and doesn’t need conversing with. I simply take him about with me to prevent people meeting me and saying, the way they do, “What, child, all alo-one by yourself?” which is so irritating.

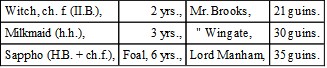

He never interferes, he trusts me, he likes me. He is the son of Sir Edward Fynes of Barsom, and they keep horses. I might say they eat horses and drink horses and sleep on horses there. Ernie wants me to like him, so he brought me a list of his father’s yearlings, with their names and weights and what they fetched at the sale written out in his own hand. It interested him, so he thought it would interest me. It must have taken him hours to do, and when he put it into my hand, and ran away, what amusement do you think I could get out of this sort of thing?

And so on for a page of foolscap. Rather an odd sort of love-letter, but I saw he meant it, and didn’t tease him.

Ernie and I moon about all the evening and watch the others. It is not etiquette to interfere with a lady who has her own cavalier, and that is why I annex Ernie, as Lady Scilly does Simon. We don’t dance. I don’t care to begin the dance racket till I am out and forced, not I, nor do I suppose the grown-ups want a couple of children getting into their legs and throwing them down. No, I watch them, and Ernie watches me.

Simon Hermyre and Lady Scilly dance half the time together. I suppose it is de rigueur. And when they are not dancing they are talking of money. I have heard them. I don’t mind listening, for, of course, money isn’t private. And I think it revolting to talk business on moonlight nights by the sea. They argue about bulls and bears and berthas, which puzzled me at first, till Ernie told me they did not mean either animals or women. Simon is not at all interested in any of them. Ernie (who is at Eton) says it is because he has nothing on, and only talks about stocks to please her.

Simon does not talk about dirty money when he is with my sister, he does not talk much about anything, and yet they seem to be enjoying themselves. Perhaps Ariadne is a rest after Lady Scilly?

One damp evening, Ariadne and he came out of the big hall together, but before she sat down in her white dress on one of the iron seats outside, Simon carefully wiped it with his handkerchief, though it hadn’t been raining. Then, without thinking apparently, he put it up to his own forehead.

“Phew! I’m hot,” he said. “It’s a weary old world! Hope I die soon!”

Simon talks broad Yorkshire, I notice. Lady Scilly had been Simon’s partner before Ariadne, and I had passed with my boy—that’s what the grown-up women always call their special men!—just as Simon had taken out his nice gold-backed pocket-book with his initials in diamonds that I envy him so.

“Blow these wretched figures! They won’t come!” I heard him say.

“On they come fast enough, not single spies, but in battalions,” Lady Scilly had answered pettishly; “what I complain of is that they won’t go! See if you can’t pull me through, dear boy.”

I thought it indecent of her to make poor Simon do her sums for her, on a heavenly night like this, when the tide is fully in, and all you can see through the white rails of the Esplanade is a soft creeping heap of dark water, like a pailful of ink. Simon now got up and looked down into it, and his forehead became one mass of wrinkles, like a Humphrey’s iron building.

And Ariadne got up too, and looked into the water with him, but she said nothing. I know her pretty well, and that it was because she had nothing to say, and as he evidently didn’t want her to say it, it didn’t matter. She had put her hand on the railing, and it looked very nice and white in the moonlight somehow, quite like a novel heroine’s, so she is repaid for her trouble and expense in almond paste-balls. Simon Hermyre looked at it, as I used to stand and look at a peach or an apple on the wall when I was little. He would have liked to pick it, as I would the apple or peach, and hold it tight in his own hand, I thought, but he didn’t, but sighed instead and said—

“I wish I had a mother!” That wretched Ernie boy began to giggle. I nearly smothered him, for I wanted to hear what Ariadne would say.

“Do you?” she said. “I have.”

Did any one ever hear anything so stupid and obvious? Yet Simon seemed to like it, for the next thing he said was—

“Why don’t I know your mother? I expect she is gentle and sweet like you.”

I have no doubt Ariadne would have been imbecile enough to answer Yes, not seeing the pitfall there was hidden in the words, but at that very moment George and Lady Scilly came out with a lot of other people. They came drifting along to the balustrade where we were, and Lady Scilly put her hand on Simon’s shoulder very lightly, and George put his heavily on Ariadne’s.

Simon whisked away his shoulder and wriggled as much as he dared. Ariadne of course could not move at all. She said afterwards she felt as if it was her own marriage-service, and that George was “giving this woman away” quite naturally. He likes to see her with Simon and shows it, it is the only time in his life that he is what they call fatherly.

Lady Scilly gave Simon two taps. “I love this thing, you know,” she said to George. Then, going a little way back—“Just look at them! Isn’t it idyllic? Romeo and Juliet spooning on a balcony over the sea instead of over a garden, and with a squawking gull instead of a nightingale to listen to. And I—poor I—am Romeo’s deserted Rosaline. Did Rosaline take on Mercutio, I wonder, when she had had enough of Romeo?”

She glared up at George, and the moonlight caught her face the wrong way and made her look old. All the same, she would not have dared to say all this if she hadn’t felt sure of Simon, and it proved that he hadn’t been silly enough to make her think it worth while to be jealous of Ariadne.

“I always thought Mercutio by far the most interesting character in the piece. Come, good Mercutio! Romeo, fare—I mean flirt well!”

They turned away and left Simon grinding his little pearly teeth.

“I consider all that in beastly taste!” he said, whacking the rail with Ariadne’s fan. Of course it broke, and Ariadne cried out like a baby when you have smashed its favourite toy.

Simon was thoroughly out of temper with all the world, Ariadne included. Lady Scilly had called him Romeo; well, he was jealous of Mercutio! Such is man—and boy! He spoke quite crossly to Ariadne.

“I’ll give you a new one. I’ll give you twenty new ones. Let us go in and dance—dance like the devil!”

Ernie told me a great deal about Lady Scilly after they had all gone in. He knows a lot about her, through his father, who has a place near the Scillys in Wiltshire. He says his father says that at this present moment she hasn’t got a cent to call her own; what with gambling, and betting, she is fairly broke. I wish, then, she would try to borrow money off George—just once—for that would choke him off her soonest of anything, and then he would perhaps be nicer to mother?

Ariadne would not go to bed at all that night. She sat in the window, eating dried raisins, just to keep soul and body together. And all the time her affairs were progressing most favourably. She was vexed because she saw that Lady Scilly did not consider her worth being jealous of. I told her she was never nearer getting Simon than now when he was bringing a heart that Lady Scilly had bruised by sordid monetary considerations to her, to stroke and make well by her soothing ways. And Ariadne is soothing, she can do the silence dodge well. She is a regular walking rest-cure, I tell her, for those that like it.

Simon was unusually nice to her all the next week, just as I prophesied he would be. Then an untoward event happened.

There were dances at the Saloon only once a week. Next night a conjuror came to the Saloon Hall, called Dapping, and Aunt Gerty took us, paying one shilling each for us. There were worse seats, only sixpence, but there were also better, viz. the first four rows were three shillings. The Scilly party with Irene Lauderdale were in them, and on the other side, very obviously keeping themselves to themselves, there was Sir Frederick Hermyre and Almeria, and a severe woman aunt, and Simon in attendance. The Hermyres were staying all night at the hotel, and he had to be with them for once, waiting on his father, not on Lady Scilly. It couldn’t have been as amusing for him as her party, that laughed and joked, but still Simon as usual looked quite happy as he was. He would have thought it rude to look bored, and he did look so nice and clean, with his little retroussé nose next to his father’s beak, and Almeria’s large knuckle-duster of a proboscis framing them. I don’t suppose Simon even knew Ariadne and I were there, for we were a long way behind, and he doesn’t love Ariadne enough yet to scent her everywhere. Next us was Mr. Bowser, Aunt Getty’s mash, as she calls him. I believe she had told him we were to be there. Ariadne and I were disgusted at being mixed with Bowser, and tried to make believe we were a separate party, and talked hard to ourselves all the time. Ariadne was in a white muslin she had made herself—window-curtain stuff from Equality’s sale. It was pretty, but casual. She never will have patience to overcast the seams or settle which side they are to be on, definitely. She had made her hat too, of chiffon with a great trail of ivy leaves over the crown. I wished she had been dressed more soberly, considering the company we were in.