Полная версия

The Key to the Indian

It might be a bit of a problem, though, leaving Gillon behind.

He was really getting worked up about the camping trip. He kept calling through the thin dividing wall between their two bedrooms, keeping Omri awake more than ever.

“I’m going into town tomorrow after school to get a camping mag. They’ll have proper ads in them for gear, and articles to read and stuff.”

“Mm.”

“It’s not true that Mum’s the only one who’s camped. Remember Adiel went to the Brecon Beacons with his class?” Omri pretended to be asleep and didn’t answer. “Omri? Remember?”

“Yeah.”

“He said it was grisly,” called Gillon, but with relish, as if ‘grisly’ was good. “Rained the whole time. And he got lost in a bunch of mist and hurt his leg sliding down some rocks and they had to hunt for him for hours. His teacher thought he was dead, for sure! Om?”

“Mmm.”

“You still awake? I’ve heard of lots of hikers and climbers getting lost on Dartmoor! One lot died of exposure. We’d better buy some rope and rope ourselves together. We’ll need proper climbing boots, knapsacks, sleeping bags… maps, compasses… a stove…” His voice finally petered out on a lengthy list of prospective purchases.

Omri was nowhere near sleeping. He was actually sitting up. He’d switched on his pencil torch and was making notes. Maps and compasses… Could you get maps of north-eastern United States back in the eighteenth century? Sleeping bags, knapsacks and a stove certainly sounded as if they’d be useful. If only they could take them!

He kept imagining himself, and his dad, in the car. They could put all the stuff they’d need in there. If you were touching a sleeping bag that was wrapped round a bunch of other useful stuff, it would all go back. They’d have to really think hard. It would be no use wanting to pop back from Little Bull’s time to get something they’d forgotten.

Wait.

The car.

Omri could see himself and his dad sitting in the front seats of the car, which was parked in some remote spot, with the bundles of stuff they were going to ‘take back’ on their laps, and his dad with the key, the magic key.

How to lock the car? With the window open, reach through it and stick the key in the door from outside?

Or put it in the ignition?

Omri suddenly jumped out of bed and went to where the cupboard was standing in the middle of the new shelf. The key was in the lock. He took it out and looked at it. His heart sank.

The key was magic, yes. And it was a ‘skeleton’ key, that would fit a lot of locks. But car keys were different. They were a different shape. They weren’t cylindrical, for one thing. They were flat.

Omri suddenly knew, without any doubt, that no way would the magic key slide into either the door lock or the ignition of their car. This wasn’t going to work.

Yet there was no doubting the signs. The numberplate, C18 LB, was like a summons. The car was their cupboard, all right. It was just a matter of solving this little key problem.

This called for a consultation.

Clutching the key tightly, he tiptoed through Gillon’s room to the head of the stairs at that end of the house. This was a Dorset longhouse – not like an Iroquois one, but a special kind they had in this part of England, one room deep with stairs at each end, no corridors. He crept down the narrow wooden stairway, which opened into the last little sitting room at this end, that his parents had designated as a TV-free zone. As he’d hoped, his dad, who didn’t like TV much, was sitting there reading.

“Dad!” Omri hissed.

His father looked up. “Hello, Om. What’s up? Can’t you sleep?”

“Where’s Mum?”

“Watching something ghastly about hospitals. Ber-lud everywhere,” he added, quoting Gillon.

Omri glided over to him. “I’ve thought of something ghastlier. Look at this key. Think of the car.”

His father took it from him and examined it. “Oh hell,” he said softly.

“See? It’s not going to fit.”

“Of course not! Why didn’t I think of that? I was so excited about the numberplate…”

Omri sat beside him on the mini-sofa. “What’ll we do?”

They sat silently for a long time, thinking. Omri had time to notice that the book his dad was reading was one of his books about Indians – his dad must have gone into his room earlier and taken it from his ‘library’. It was a huge tome called Stolen Continents that Omri had bought second-hand. Now it slipped to the floor and neither of them picked it up.

The whole adventure was poised on the edge of being aborted. Before it had even begun.

“You know, Omri,” his father said at last, “there is an answer. There’s got to be. The trouble for me is, I don’t know enough about the whole business to find the solution. I’ve been thinking. That story of yours, that won the Telecom prize. That was true, wasn’t it – I thought at the time it had an absolute ring of truth. So I know about the first part. But a lot has happened since then – developments. I think what you’d better do is try to tell me everything.”

“Now?”

His dad looked at his watch. It was only ten pm. “Are you tired? It’s school tomorrow.”

“I couldn’t possibly sleep.”

“Okay, start talking. Keep your voice down.”

Omri talked for an hour.

He told about how he’d brought Little Bull back after a year, just to tell him about his winning story, and found he’d been wounded in a raid on his village and left to die. Only Twin Stars going out to find him and lug him somehow on to his pony – and then Matron, who’d proved as good as any surgeon, taking the musket-ball out of his back – had saved him.

He told Patrick’s adventure, back in nineteenth-century Texas, how he’d met Ruby Lou, a saloon-bar hostess, and how they’d saved Boone, Patrick’s cowboy, from dying alone in the desert. How Omri had brought him back just as a hurricane had hit the cow-town, and the hurricane had come back with him.

He kept remembering things and wanting to go back, or off at a tangent. His father, who had had a notebook and pencil at his side while reading Stolen Continents, made notes.

When Omri came to the recent part, about Jessica Charlotte, he was getting really sleepy.

His dad interrupted. “Listen, why don’t you just give me the Account to read for myself? And you get off to bed.”

So Omri tiptoed upstairs again and fetched Jessica Charlotte’s notebook. He carried it reverently downstairs and put it in his father’s hands, and stood there while he stroked its old leather cover and ran his forefingers around the brass corner-bindings.

“It’s fascinating, almost magic just holding it,” he said. “I can’t wait to read this. Go on, bub, get some sleep.” Just as Omri was starting up the stairs, his dad added: “Don’t keep yourself awake, but do Mum’s trick.”

“What’s that?”

“Mum says that when she’s got a problem, she thinks about it last thing before she drops off. She swears her subconscious works on it while she’s sleeping, and sometimes in the morning the solution just appears.”

So Omri did ‘Mum’s trick’. As he lay, drifting off to sleep, he thought about the two keys – the cupboard key, and the car key. He laid them side by side in his imagination. They were so different that anyone who didn’t know what a key was, wouldn’t have seen a connection between them. It seemed extraordinary, even to Omri who had always taken the function of keys for granted, that something so small could make the difference between being able to open a door or make a car go, or be completely stymied.

And in this case, it was the difference between being able to go back into the past, or being stuck here. Between being able to have a great adventure, and not. Being able, maybe, to help Little Bull in his dire trouble, and having to leave him and his tribe to their fate.

There had to be an answer. There had to be.

3A Surprising Ghost

Omri woke up early the following morning. Before he’d even opened his eyes, he ‘looked’ at the two keys, still lying side by side in his imagination as they had been in his last, sleepy thoughts the night before. His body stiffened. One of the keys had changed!

It was the car key.

He’d often seen it in reality, hanging in a box of little hooks inside the front door of the cottage, where his father and mother always hung it as soon as they came in from driving so it wouldn’t get lost. Last night, when he’d visualised it, it had been the key he knew – a flat metal key with a round, flat top made of some plastic material with an ‘F’ for Ford imprinted on it.

Now the key, as clearly in his mind as if he could see it in front of his eyes, no longer had the round black plastic bit at the top. It was all metal. It was as if the whole key had been remoulded.

He sat up sharply in bed. Remould the key!

How could they? And if they did, what good would it do? Only the magic key could take them back in time.

Unless…

He jumped out of bed and barged through into his parents’ bedroom, which adjoined his. The door flew backwards, hitting his father, who was doing the same manoeuvre in reverse, and nearly knocking him flying.

“Shhhh!” they both hissed, and then stifled laughter. Omri could see his mum’s shape under the duvet, still sound asleep. It was far too early for her to wake up – not much past six o’clock.

Omri backed into his own room and his dad followed, closing the old-fashioned plank door silently behind them and lowering the latch so it wouldn’t click. Then he turned to face Omri. He looked very tired, but his face was flushed with suppressed excitement.

“You’ve thought of something!” Omri guessed at once.

“We’ll have to whisper. Listen.” Omri now noticed he was holding Jessica Charlotte’s notebook. “I read this, all of it, last night. It has got to be the most extraordinary, fascinating, amazing thing I have ever read. Of course I’m crazy about old diaries and stuff from the past. God, when I read something like this – what am I talking about, there IS nothing like this, this is unique, but when I was reading it I got so caught up, wanting to know more and more about the time she lived through, the First World War, and the period before that – it was like having her right in the room, telling me—”

“Yeah, Dad, I know, I read it, I know just what you mean. But about the key.”

“Yes! Well! Isn’t it obvious? I mean, Jessica Charlotte made the magic key. She fed her ‘gift’ as she called it, into it without even meaning to. Remember what she said?” He was searching through the yellowing pages, and found the place, marked with a match. “Yes, here! I hardly knew it then – I only knew I was bending all my strength on making the key perfect, and I felt something go out of me, and then the key grew warm again in my hands as if freshly poured, and I knew it had power in it to do more than open boxes. But I didn’t know what. I only knew my heart had broken and that I would have given anything to have it be yesterday and not today.”

He looked up. He had a strange expression in his eyes, almost as if he were on the brink of tears. “Poor woman,” he said, his voice full of pity. “You can understand it so well. She’d just seen her beloved little niece Lottie – who was your grandmother, Mum’s mother whom Mum never knew – for the very last time. She must’ve been full of bitterness and sorrow, and anger against her sister for saying – well, implying – that she wasn’t good enough to be with that little girl she loved more than anyone in the world… You know what I figured out, Om? If a person has any sort of magic gift, it gets more powerful the more strongly the person’s feeling. Like her son, Frederick, putting magic into the cupboard because he was so angry about plastic ruining his toy business.”

“Yeah, Dad. I read it, you know.”

“Om, please, don’t be impatient. Let me work my way through this. You had days, maybe weeks, to read the Account and digest it. I had it all in one go and it’s fairly knocked me sideways. I didn’t sleep a single wink last night.”

“Sorry – I didn’t mean—”

“No, it’s okay, it’s okay. Give me a sec, and I’ll cut to the chase.” But his head was down, he was still turning the pages of the notebook. “It’s just, I’m so utterly gobsmacked about Jessica Charlotte and her story, I’ve half-forgotten about Little Bull…” He looked up at Omri. “But yes, the key. It came to me. Now listen. If we could find a figure, a plastic toy, that might be Jessica Charlotte – I know it’d be difficult, but there can’t be that many figures that look like her – if we could… and if we could bring her forward in time, to us, we might ask her to copy the car key for us. She could make it magic, the way she did the other.”

Omri stared at him, his brain racing. Of course! A slow, face-filling grin spread over his features, and he saw an answering look of incredulous delight dawn on his father’s face.

“Don’t tell me you’ve got one!”

“Yes! We’ve already brought her once—”

“What!”

“Shhh! I haven’t had a chance to tell you everything. I was concentrating on Little Bull…”

“You brought her! You’ve met Jessica Charlotte!”

For answer, Omri dived under the bed and got out another of his treasures – an old cashbox, black and silver, the paint wearing off, a blob of red sealing-wax still blocking the slot. He opened it cautiously. His father was so eager he was trembling. Omri carefully took out the little woman-shape in the red dress with the big plumed hat, the size of his finger. His father took it from him as reverently as if it were a holy relic.

“This is her?” he whispered wonderingly.

“Yes.”

“Where did you get it?”

“It was in here, in the cashbox that I found with the Account, buried in the old thatched roof. The magic key opened it. She was fast asleep, but later I – well, me and Patrick—”

“Patrick and I—”

“Yeah, well, she woke up, and we decided… I mean it was just before she was going to steal her sister’s earrings, you know, the night she made the key. And I wanted to change her mind and get her not to steal them…”

His father’s face sagged suddenly with horror. “My God, Omri! You didn’t, did you?”

“No. Patrick said not to. Because if I had, it would have changed history. Everything that came from stealing the earrings – things linked to other things, like a chain – wouldn’t have happened, and I – I might never have been born.”

His father swallowed hard. His face had gone very pale. “I wonder if we ought to be meddling with this,” he said at last. “I wonder if we ought not to just – just put the key, and the cupboard, and the cashbox, and the Account, the plastic figures and everything else, safely away somewhere and – and just forget it.”

“No, Dad! It’s no use. I tried that. I did try – you know I did – I put the cupboard and key in the bank and I swore I wouldn’t take them out and mess about with the magic any more, but – but you can’t not, somehow. I couldn’t, anyway. It – when I read the Account, I – I just felt the magic calling me.”

His father was gazing at him with a very strange, troubled expression. “Omri. You don’t suppose—”

“What?”

“Well… don’t be scared. But Frederick obviously inherited some part of Jessie’s ‘gift’, or he couldn’t have put magic into the cupboard he made. I just wondered if that – magic power – if… After all, they were your blood relatives. Perhaps it’s something that can be – passed on.”

There was a long silence. They stared into each other’s eyes.

“Wouldn’t…” Omri found he had to clear his throat. “Wouldn’t – Mum have had some of it?”

His father frowned and went to the window. It was framed by deep eaves of thatch. The sun was just coming up over the hill on the horizon, the one that had on its top a strange little circle of trees, like a peacock’s crown.

“I suppose Mum never told you about the time she saw a ghost.”

Omri jumped. “A ghost!”

“Yes. She told me about it ages ago. I didn’t believe her. Of course. I didn’t believe in anything unprovable in those days.”

“Whose ghost did she see?”

“Well, that’s one of the things I was thinking about, lying awake last night.” He looked down at the little woman-shape in his hand. “I only have her description to go on, and I only heard the story once. Years ago, before we were married. She told it to me when I was saying I didn’t believe in anything supernatural, including an afterlife. And she disagreed, and we were sort of quarrelling. She told me this story, to prove me wrong. And I…” He paused, and swallowed, “I laughed.”

“Tell me!”

“She said she was visiting her mother’s grave – Lottie, who’d died in the bombing of London, when your mum was still a baby. Lottie was buried in the same grave as her father, Matthew, in Clapham Cemetery, near where she was born, where her mother still lived. Jessica Charlotte’s sister.”

“Maria.”

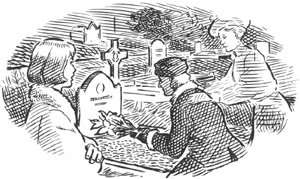

His father nodded. “Yes. Maria, who brought your mother up. She was an old lady by then, in her eighties, but she went every week to the cemetery to put flowers on Lottie’s grave. Mum didn’t often go because she was busy with her own life by then, she was a student, but that day Maria wasn’t well and Mum felt she had to drive her to Clapham instead of letting her go by herself on the bus. Mum said she felt guilty about not taking her gran more often but you know, if you don’t even remember the dead person, it’s hard to visit the graveyard regularly.

“Anyway, they got there, and bought some flowers at the gates, and the old lady filled a plastic bottle with water from a tap. Mum carried the things and held her gran’s arm, and they walked to the grave. And then Mum gave the flowers to her gran, who knelt down by the grave. She was – you know – taking out last week’s flowers and arranging the new ones in the vase with the fresh water, and suddenly Mum saw someone standing beside her.”

Omri sat rigid. He felt as if ice-water were trickling down his spine. He could see it in his mind’s eye. He saw the whole scene as if it were being enacted in front of him. He even saw who his mum had seen, before his father went on:

“She could see her clearly. A woman in an old-fashioned long dress with her hair piled up on her head. There was a strong breeze blowing, but the woman’s hair didn’t stir. She was looking straight at Mum.”

Omri wanted to ask his dad to go on, but he felt frozen, frozen in the scene. He hardly needed to ask. He saw.

The woman was Jessica Charlotte.

She took a step forward, nearer to the grave, looking all the time at the young girl standing on the other side of it. She put her hand – wearing a long black glove – on the shoulder of the bent old woman, busy with the flowers, who didn’t seem notice. She patted her gently. She smiled a sad, sad smile at the young girl who was going to be Omri’s mother. And she nodded tenderly down at the old lady, as if to say, “See how old she is. You must take care of her now.” Maybe she even did say it. And then suddenly she wasn’t there any more.

Omri’s father was talking. He was describing the scene just as Omri saw it in his head. Which came first – what Omri saw, or what his dad said?

When his dad finished, there was a silence, and then Omri said in a choked voice, “Mum must have felt awful.”

“About seeing the ghost?”

“No! About all the times she hadn’t taken her gran to the cemetery. About the ghost needing to come and – and remind her to take care of Maria.”

“Do you think the ghost – was Jessica Charlotte?”

“Of course it was,” said Omri simply.

“You sound sure.”

“I am.”

“Omri – how can you know that?”

“Well it’s not because I’m magic. It’s just – I’ve got a very good imagination, and sometimes it just tells me things.”

His father looked at him, and Omri heard what he had just said, heard it as his father must have, as proof that Omri had a bit of Jessica Charlotte’s gift.

They talked it all over very carefully before anyone else in the house woke up. The sun was well clear of ‘Peacock Hill’ and streaming into the room before they first heard the others beginning to stir, and had to stop.

Omri, though of course he wanted to see Jessica Charlotte again, and thought it very probable that she would have the ability to make them another magic key, one that would work in the car, was very doubtful just the same about his dad’s plan.

There was nothing in the Account about her making a second time-journey. The first one – when she visited Omri and Patrick and sang them a music-hall song – was hinted at in her diary, but nothing after that. Surely if she had been brought a second time, and asked to make another key, she would have remembered it, especially so close after the first time.

Omri’s father was very interested in the time question. “Does it work the same at both ends?”

“Yes.”

“That’s to say, if a week has passed here, a week has passed for the people in the past?”

“That’s right. I know because when Little Bull came this last time, his baby was about a year old, and it was a year here since he was born. Anyway, I knew it before.”

“Okay, so let’s work it out. How many days is it since Jessica Charlotte came?”

Omri thought about it. A week had passed between seeing her, and the day his dad had found the figures and discovered the secret, and three days more had passed since then.

“Ten days.”

“Ten days…” His dad was looking at the notebook. “So. Right after she came here – no, it wasn’t. Let me see. She made the key. That was the day of the victory parade, the day she said goodbye to Lottie, Armistice Day – November the eleventh, nineteen-eighteen. The next day she went back to Maria’s to ‘say goodbye’, pretending she was going abroad. And that was the day she stole the earrings. So that’s one day.

“Then, she writes, a week went by. And at the end of that week, she got the news that little Lottie had been accused of stealing the earrings, and had run out of the house, and her father, Matthew, ran after her and got run over and killed. And that’s where her part of the Account ends.”

“Well, there is a bit more…”

“Not that you can read. When she got to writing that part, all those years later when she was on her deathbed…” he looked up, and looked around. “Maybe in this very room, Omri!”

“No, it was Gillon’s room.”

“How do you know?”

“I just—” He stopped suddenly. He was beginning to feel creepy about this. He did ‘just know’, he was certain. But how?

His father took a deep breath, and went on. “Okay. Anyway, when she was trying to write the last of the Account, she became too ill and weak, and had to call in her son Frederick to finish it. This last page of her writing…” He pointed to faded, scrawly words that you could hardly make out. “… indicate to me that she was not only very ill by the time she came to write it, but that she was writing about a time when she was almost crazy. She felt Matthew had died because of her, that Lottie had been falsely accused, that more terrible things were going to happen because of what she’d done.

“Now, Omri, if you’ve got a bit of her ‘gift’, use it. Imagine her as she was – is – at this moment. Ten days after the theft of the earrings. Three days after she found out about Matthew’s death.”