Полная версия

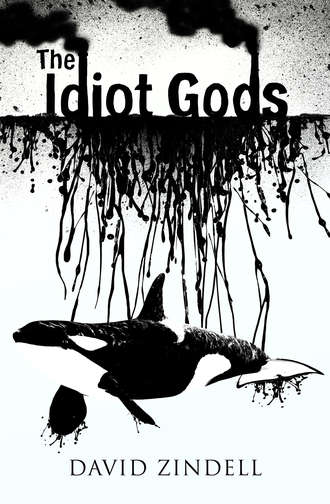

The Idiot Gods

I could not quenge. Try as I might, I could not find my way into the ocean’s innermost part. The loss of life’s most basic gift stunned me and terrified me even more. Something was wrong with the world, I knew, and something was hideously, hideously wrong with me.

How I wanted to join Pherkad then! The humans might as well have stuck their wooden splinters into me. Better to fall blind, better to fall mute, better to fall deaf. If I could not quenge, what would be the point in remaining alive?

Upon this thought, the burning that had tormented me grew even worse. Gouts of flame torn from the sun seemed to have fallen upon me. Fire laid bare my tissues one by one and worked its way deep into the sinews of my soul. It opened me completely. In doing so, it finally opened me to the meaning of the note that had whispered so urgently when the bear had died and had cracked out like a lightning bolt after Pherkad had left us. Now I could hear Pherkad calling to me even as Baby Electra called along with the myriad voices of the Old Ones.

The whole world, it seemed, was calling, and I finally heard the sound of my destiny, or at least a part of it: that which I most dreaded doing, I must do. How, though, I asked the cold, quiet sea, could I possibly do it?

2

I wish I could say that I leaped straight toward this destiny, as a dolphin breaches in a graceful arc and snatches a flying fish from the air. I did not. I doubted and hesitated, and I equivocated when I asked myself why I seemed to lack the courage to act. I tried not to listen to the call, even though I could not help but listen to its imperative tones during my every waking moment and even while I slept. It pursued me as a band of Others might hunt down a wounded sea lion. It seized me and would not let go.

I spent much time reflecting on my life and life in general. Had it not been, up to the moment I had met the bear, much like the life of any orca? Had I not had good fish to feast upon and the love of my family? Had there not been songs to sing and wonders to behold? Had anything at all been lacking in such a paradise?

And yet the ocean’s voice seemed to call me away from all my happiness – but what was it calling me toward? What did it want of me? I knew only that it had to do with my gift for languages, and I sensed that this gift would become a very great grief, and soon.

I might never have acted at all had it not occurred to me that my childhood contentment had already been destroyed. I could not quenge. I could not – no matter what I tried to do to restore myself to that most natural state.

At first, I tried to hide my affliction from my family. I might as well have tried to hide a harpoon sticking out of my side. One day, while my grandmother was reviewing the tone poem that I could no longer work on, she asked me to counterpoint the penultimate melody with Alsciaukat the Great’s Song of the Silent Sea. I could not. When I attempted to do so, I sounded as inept as a child.

‘Quenge down along the chord of the first universal,’ my grandmother said to me. ‘If you are to complete this composition, you must quenge deeper than you ever have.’

The concern in her soft voice tore the truth from me in a shout of anguish: ‘I cannot quenge at all, Grandmother!’

I told her everything. I explained how the bear would not stop roaring inside me, where his voice joined Pherkad’s cry of rage. All my thoughts, I said, had fixed on human beings as one’s teeth might close about a poisonous puffer fish. I could not expunge the images of the two-leggeds from my mind.

‘Then you must meditate with more concentration before you quenge,’ my grandmother said. ‘You must clear your mind.’

‘Do you think I have not tried?’

‘I am sure you have. Before doing so, however, you must also clear your heart.’

‘How can I? Poison is there, and fire! A harpoon has pierced me straight through!’

‘What, then, will soothe the poison and draw the harpoon? What will extinguish the flames that consume you?’

‘I do not know!’

This was another equivocation. I had a very good idea of what might restore me, even though I could not understand how it possibly could.

‘Strange!’ she said. ‘How very strange that you should believe you cannot find what cannot be lost. It is as if you are swimming so quickly in pursuit of water to cool the fire that you cannot feel the ocean that could put it out.’

‘I know! I know! But the very knowingness of my plight makes me want to escape it all the more and to swim ever faster.’

My words troubled my grandmother more than I had ever seen her troubled, even when Baby Capella had been stricken with the fever that had eventually killed her. My grandmother called for a conclave of the family. We sang long into the hours of the midnight sun, discussing what was wrong with me and what might be done.

‘I have never heard of an orca unable to quenge,’ Alnitak said. ‘One might as well imagine being born unable to swim.’

‘I have never heard of such a thing either,’ Mira agreed. ‘It does not seem possible.’

‘To quenge is to be, and not to quenge is to be not. But how could that which is ever not be?’

And my brother Caph added, ‘Is it not said that the unreal never is and the real never is not? What could be more real than quenging?’

‘Didn’t Alsciaukat of the Sapphire Sea,’ Turais asked, ‘teach that quenging can be close to madness? Perhaps Arjuna, in his attempt to ease his grieving over Pherkad, has tried to quenge too deeply.’

My practical mother bent her tail to indicate her impatience with these sentiments and said, ‘Are we to speculate all night on such things? Or are we to help my son?’

‘How can we help him?’ Mira said.

It turned out that Chara had heard a story that might have bearing on my situation. She told of how an orca named Vindemiatrix had once lost his ability to quenge due to a tumor growing through his brain.

‘Very well,’ Alnitak said, ‘but did the tumor destroy Vindemiatrix’s ability to quenge or merely impair his realization that he could not help but retain this ability no matter what?’

‘In terms of Arjuna’s life,’ Haedi asked, ‘is there a difference?’

Now it was my grandmother’s turn to lose patience. The taut tones in her voice told of her own dislike for useless conjectures: ‘It is not a tumor that grows in Arjuna’s brain – though we might make use of that as a metaphor.’

‘How, Grandmother?’ Porrima asked.

‘That which grows often may not be killed directly. Sometimes, though, it might be inhibited by other things that grow even more quickly.’

‘I have an idea!’ young Caph said. ‘Let us make a lattice of ideoplasts representing the situation so that Arjuna might perceive in the crystallization of the sounds the way back to himself.’

‘Good! Good!’ young Naos said. ‘Let us also make a simulation of quenging so that Arjuna might be reminded of what he thinks he has lost.’

‘And dreams,’ Dheneb added. ‘Let us help him dream more vividly of quenging when he sleeps.’

‘We should recount all our best moments of quenging,’ my sister Turais said, ‘so that Arjuna might remember himself.’

‘Very well,’ my grandmother said, ‘we shall do these things, and we shall sing to Arjuna, as we sing to a child to drive away a fever. We must sing as we have never sung before, for Arjuna is sick in his soul.’

And so my family tried to heal me. We swam on and on toward the ever-receding western horizon where dark clouds hung low over choppy seas. I felt the sun waxing strong as summer neared its solstice, though the clouds most often obscured this fiery orb.

Nothing, it seemed, could cool my wrath of despair. The songs my grandmother poured into me – rich, sparkling, lovely – came the closest to helping me dive once more into the waters of pure being. So deep did I wish to dive, right down to the magical Silent Sea, lined with coral in bright colors of yellow, magenta, and glorre! So full of my grandmother’s love did I feel that I almost did – almost.

However, the harder my family worked to make me whole, the more keenly did I become aware of what I had lost. I partook of their quenging vicariously, which made me long all the more bitterly for my own. In the end, my family could do little more for me than reassure me of their devotion. All their stratagems of representing, simulating, dreaming, remembering, and even singing failed. All are quenging, yes, and yet are not – not unless done with an utter awareness that one is quenging in doing them.

‘Thank you,’ I said to my family, ‘you have done all that you could.’

It was a day of layered clouds in various shades of gray pressing down upon the sea. The waters had a brownish tint and seemed nearly lifeless, colored as they were with the umber tones of my family’s despondency.

‘What ails you?’ Caph cried out in frustration.

His anguish touched off my own, and I cried back, ‘The humans do!’

I could not help myself. I told Caph and the rest of my family of the call that I heard and all that I had so far concealed.

‘Poison is there in me, and fire!’ I said. ‘A harpoon has pierced me straight through! The humans have done this thing, and only the humans with their hideous, hideous hands can draw it out.’

‘How? How?’ Caph asked me.

‘We must journey to the humans,’ I said. ‘They are the cause of my sickness, and they must also be the cure.’

‘But how?’ Caph asked again. ‘You have not said how they could help you.’

‘I do not know how,’ I said. ‘That is why we must go to the humans and talk to them.’

Caph laughed at this, sending bitter black waves of sound rippling through the water.

‘Talk to the humans? What will we say to them? What do you expect them to say to you?’

One could, of course, talk to a walrus, a crab, even a jellyfish. And each could talk back, in its own way. Caph, however, sensed that I was hinting at communicating with the humans on a higher level than that of the common speech of the sea.

‘We must ask the humans why they killed Pherkad,’ I said, ‘and how they set fire to water. We must speak to them, from the heart, as we speak to ourselves.’

Alnitak swam up and moved his massive body between Caph and me. ‘We could speak all we wish, but how could the humans possibly understand what we say?’

‘We can teach them our language,’ I said.

At this, Alnitak began laughing in bright madder bands of scorn, and so did Turais, Mira, Chara, and Caph. I might as well have suggested teaching a stone to recite the fundamental philosophical mistake. All things have language, yes, but everyone knew that only whales possess the higher orders of intelligence and the ability to reason and speak abstractly. Only whales make art out of music. And surely – surely, surely, surely! – whales alone of all creatures could quenge.

Baby Porrima, the most innocent of my family, asked me, ‘Do you really think the humans could be intelligent like us?’

Before I could answer, Caph said, ‘We have watched their winged ships that fly through the sky and land upon the water. Have we any reason to suppose that the humans are more intelligent than the geese who do the same, but with much more grace?’

‘I should not put their intelligence that high,’ my sister Nashira said in her bewildered but beautiful voice. ‘We have all beheld the ugliness of the metal shells that carry the humans across the water. Even a snail, though, within its perfectly spiraled shell, makes a more esthetically pleasing protection. I should say that the humans cannot be more intelligent than a mollusk.’

Her assessment, though, proved to be at the lower end of my family’s estimation of human intelligence. Dheneb argued that humans likely surpassed turtles in their mental faculties even though it seemed doubtful that they had figured out how to live as long. Chara placed the upper limit of the humans’ percipience near that of seals, who after all knew well enough not to swim in shark-darkened waters whereas the humans did not. My grandmother futilely reminded us that intelligence could not be determined from the outside but only experienced from within. Finally, after much discussion, my family reached a consensus that humans were probably about as smart as an octopus, whose grasping tentacles the humans’ hands somewhat resembled. Their generosity in according humans this degree of sentience surprised me, for the octopi are among the cleverest of the ocean’s creatures, even if they cannot speak in the manner of a whale.

In a way – but only in a way – my family played a game in this guessing in order to sublimate their disquiet. We all knew that humans possessed a strange, fell power. None of us, however, wanted to entertain the notion that this power might derive from anything like that which we knew as intelligence. None of us except me.

‘We cannot say if humans might learn to speak our language,’ I said, ‘unless we try to teach them.’

Everyone, of course, recognized the logic of my argument, and so it saddened me when my family rejected its conclusion.

After further discussion, my grandmother announced, ‘We cannot journey to the humans out of the remote possibility that they might be sentient enough for us to speak with them. It is too dangerous.’

Too dangerous! Would it be less dangerous to do nothing? The bear cried out through the water: Why did the ice melt around me? And Pherkad called to me in the bitter, beautiful tones of his death poem that told of his agony and the suffering of the entire world.

‘Very well,’ I said to my grandmother. ‘Then I will go to the humans alone.’

If a comet had struck the waves just then, the shock of it could not have been greater. No orca of our kind ever left his family.

My mother’s response cracked out swift and sure. In this instance, she had no need to confer with the rest of us.

‘You cannot leave us,’ she told me. ‘Would you tear out my heart and feed it to the sharks?’

‘You will always have my heart, as I do yours.’

‘You will die without me. And how can you think of abandoning your little brother? I need you to watch over him when I am quenging far away. You are the best caretaker I have ever known.’

‘I am sorry, Mother, but I must leave.’

My unheard-of willfulness occasioned another conclave, the longest that my family had ever held. For three days we talked as we journeyed through blue-gray water grown gelid and nearly still. Dheneb and Alnitak dove beneath icebergs so that in the denser waters of the deeps, they might hear their confidences more clearly. Turais and Chara visited with the Old Ones and drank in their wisdom, while Nashira sang again and again the melodies of the great songs that told of the deeds of the heroes of our people.

My grandmother meditated and dreamed and sang, too. She called my family to swim together. We breathed at the same moment and glided along side by side, synchronizing each beat of flipper and fluke and moving across the sea like a single wave. We breathed and let our thoughts ripple through us like a wave of shared blood as we quenged together – all save me. Like the still point of a storm, my grandmother served as the center around which all my family’s separate impulses and mentations turned and flowed and became as one:

‘Like the great north current,’ Alnitak said, ‘Arjuna will go where he will go.’

‘Can one stop the turning of the ocean?’ Haedi added.

‘Do not the Old Ones say,’ Mira asked, ‘that each whale has a single destiny?’

‘How,’ Turais said, ‘can we ask Arjuna to go on swimming with us in so much pain? Who could bear the sadness of not being able to quenge?’

Mira, having fallen nostalgic, said, ‘Let Arjuna know his old joy again. Do you remember how when he was a baby he tried to talk to Valashu, the Morning Star?’

‘How could we forget that?’ Dheneb said. ‘How can we ever forget how he talked with Pherkad, who gave him his magnificent song?’

‘The Old Ones,’ Chara affirmed, ‘say that they have heard Arjuna’s great song. It must be that he will have returned from the humans in triumph to complete his rhapsody.’

The emotion of the last few days proved too much for Baby Talitha. She began crying even as my mother said: ‘I will want to die if Arjuna leaves us, but I think I would die if he remains and is so sad that he does not want to live.’

Finally, with all my family exhausted, my grandmother gathered all their many chords into a decision that had grown more and more obvious:

‘You must leave us,’ my grandmother said to me.

‘I cannot,’ I told her. I listened to Talitha crying and crying. ‘I cannot – but somehow I must.’

My family formed into a circle in the quiet silvery water, our heads touching so that the slightest pressure of our flutes would send our words sounding deep into each other.

‘Listen to me, Arjuna,’ my grandmother said. ‘No matter how far you journey, your heart will beat with ours and we will breathe the same breath. There is nowhere that you can go that we will not be.’

We broke apart and I prepared to leave. I gathered in those vital things that would help me on my way: Alnitak’s maps of the ocean and the heavens; Mira’s taxonomy of the sea’s manifold creatures; the epics composed by Aldebaran the Great; the music of Talitha’s laughter and reverberations of my mother’s first words to me. One thing only remained that I would need.

‘Come with me,’ my grandmother said to me. ‘Let us swim together for a while.’

We moved off away from the rest of our family. It was a cloudless day, and the low sun cast long rays of light down into the dark turquoise water. There, in the calm and clarity, in the heart of the ocean where one could hear its deepest secrets, my grandmother made a present that would protect me: she gave me a charm, alive with the most powerful of all magics, that I might never lose myself on my journey and would always find my way home.

After that, I swam toward the south and east. I swam so quickly at first that the icy sea did seem to cool my ire, if only a little. Soon I found myself racing through unknown waters. If I did not distance myself from my family with all the speed that I could summon, I feared that my courage would fail and I would turn back.

After a long time I grew tired. The muscles along my belly, tail, and flukes ached. I breached, blew out a great cloud of mist, and drew in a fresh breath. I dove down a little way into the water and hung suspended in motionlessness.

The sea about me tasted odd, perhaps flavored by unusual organisms or the upwelling of minerals that were unfamiliar to me. The waters were tinted a deep violet, with undertones of an eerie cerulean blue that I had never beheld. The entire ocean glowed – with sunlight from the cold-striated sky sifting down through the water, yes, but even more from the sonance that filled the ocean’s immensity and reverberated through every drop of it. I heard the faint singing of a humpback somewhere ahead of me and the thumping of my heart much nearer. From far away came the call that had summoned me on this journey. It sounded out as primeval as the first whale’s first breath, at once plosive and soft, reassuring and terrifying, horrible and beautiful. Into it I must venture, through an ocean whose quality had grown more and more mysterious. Through this unknown realm I must find my way where all was strange, various, and new, and the water itself somehow seemed too real.

For the first time in my life, I became aware of a kind of soul-eating silence: among all the purling sounds of the sea, I could detect not the slightest note made by one of my family. Of course, whenever I wished, I could go down inside myself and listen to Talitha’s giggles or my mother’s lullabies as clearly and with as much immediacy as if these two beloved people were singing right beside me. No difference could I hear in the actuality of volume, note, or timbre. It was not, however, the same, for I could not feel the sound waves emanating from my mother’s body, nor could I see her or touch her. My family seemed to have swum off to a distantly-remembered world and to have left me all alone.

In a wave of disquiet sweeping through me, I realized that an orca sundered from his family is an orca in danger of falling mad. If Alnitak, Chara, and the others did not swim beside me and sing to me, should I then sing to myself? Were my thoughts and words to return to me untouched by the minds of my family as if I had eaten and re-eaten the same food again and again? How could I ever heal myself with my own songs? How could I know myself without the sound of their love reflecting back a picture for me to see? Did the lightning scar still mark me above my eye? Had my mother really named me Arjuna on the day of my birth or was that memory just part of a dream, along with myself and all the rest of my life?

Brooding upon such things made matters even worse. I seemed strange to myself. I could not quenge, and I did not know if I could any longer even love. I felt fearsome and new, as if I had been remade into some dreadful form that I did not want to behold.

I began swimming again. I came upon a school of herring, each of whose scales were all silvery and streaked with faint gold and scarlet bands. I swam right into the school and stunned many of the fish with a slap of my tail. Others I immobilized with zangs of sonar or confused by blowing out clouds of bubbles. So ravenous was I that I nearly began eating without asking the doomed fish if they were ready to die. I finally remembered myself, however, and I did ask. The entire school, in their ones and their multitudes, said yes.

The feast strengthened me and gave me new life. I might have died in my soul, while my harpooned heart bled out the best part of me – even so, my body and my force of will seemed to have gained a new power. I swam on at speed into the wild, endless sea.

On a day of dead calm with the water stilled into a vast blue mirror, I heard cries from far off long before I encountered the whales who had made them. I swam toward this terrible keening. After a while, I intercepted two large humpbacks, the water streaming from their lumpy, barnacle-studded bodies whenever they breached for breath. They were moving as fast as they could in the direction from which I had come. I asked them what was wrong. In their very basic and nearly incomprehensible speech, they shouted: ‘Humans blood pain death!’

Their panic communicated into me, and I considered turning around and joining them in their spasm of flight. Instead, I swam on straight toward the sea’s wavering horizon.

Very soon, one of the humans’ gray ships appeared there. I swam in close enough to make out metal spines sticking up from the top of the ship; these reminded me of a conch shell’s many points and projections. Humans – the first I had ever seen! – stood on the top of the ship, near its head. They were tending to what looked like a long piece of seaweed that connected the ship to the bloody water. A shrieking sound like metal eating metal vibrated both ship and sea, and the seaweed thing began moving toward the ship. I zanged the seaweed and determined it was made of metal, like the ship. It continued moving, and soon the whale attached to it emerged from the water tail first, even as I had been born. A moment later, I caught sight of the bloody harpoon that had torn a great hole through the humpback’s body and had killed it. The harpoon, too, was made of metal, unlike the wooden one that had killed Pherkad.

Upon this horror, panic seized me. The ship loomed above, vast and ugly, gray and angular, like a deformed mockery of one of the deep gods. How helpless I felt against this monster of metal! I wanted to fling myself away from this vile place as quickly as I could.

How, though, could I do this? Was I not an orca of the Blue Aria Family of the Faithful Thoughtplayer Clan. Had not my mother, just before my birth, instructed me in the orcas’ ways?