Полная версия

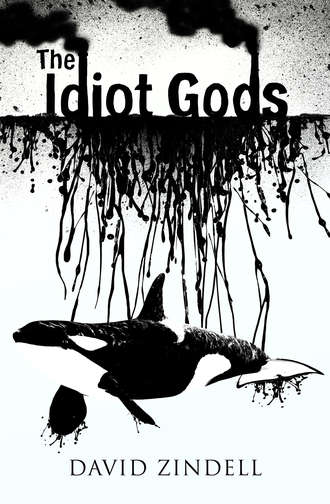

The Idiot Gods

To the first question, we have a hint of an answer in the pyrosomes: colonies of thousands of zooids a few millimeters in size that associate with each other in huge, bioluminescent tubes up to twenty meters long and two meters in diameter – capacious enough to fit a grown human being inside. To the second question, we must incline toward a resounding ‘no’ because pyrosomes and any other conceivably similar species are not complex and lack anything resembling a brain.

And yet. And yet. Compendiums of findings about the Plantae kingdom (see Tompkins’s and Bird’s The Secret Life of Plants and Mancuso’s and Viola’s Brilliant Green) suggest that trees, flowers, ferns, mosses, and the like can be said to possess a real intelligence completely absent in a brain. And then there is the recent discovery of bacteria that might need to be classified as an entirely new and seventh kingdom of life. It seems that the species of Geobacter metallireducens and Shewanella, found in certain estuaries and other aquatic environments, have evolved to strip and deposit electrons from metals and various minerals, thereby essentially eating and breathing electricity. As well, they have the ability to interconnect with each other in ‘cables’ of thousands of individual cells. It is thought that this association is facilitated by ‘nanowires’ that are an extension of the cell membrane and which can conduct electricity in a biological circuit.

Might Arjuna’s Seveners be some sort of very intelligent colonial organism assembled from bacteria similar to Geobacter metallireducens and Shewanella? We have no evidence of that, and we are skeptical that such a creature either does or could exist. It seems much more likely that Arjuna encountered (and ate) some sort of organism whose tissues produce alkaloids similar to those found in Psilocybe cubensis or Lophophora willamsii. Very intense hallucinations would account for Arjuna’s insistence that what he experienced in the South Pacific was as real as his birth or any other event of his remarkable life.

Before closing this introduction to that life, we would like to say something about two terms that Arjuna uses at various times throughout his account. The first is the name he often used to describe human beings: the idiot gods. He thought long and deep before deciding on this sobriquet. At times, he thought it much more apt to call our species the mad gods or the insane gods. However, madness can too easily be associated with anger, and although Arjuna certainly saw human beings as afflicted with wrath, as a rabid dog is lyssavirus, he did not see this as humanity’s greatest sin. Neither did he think of our kind as purely insane. Rather, he perceived in our derangement of sense and soul a willful debilitation, as if we human beings are an entire race of sleepwalkers moving through a nightmare from which we refuse to awaken. We are, he once said, like lost children wandering through a dark landscape without markers or boundaries. He had great compassion for (and dread of) our innocence. Given the horrors that Arjuna recounts, that seems a strange word to apply to the human kind, but it motivates his choice to call us idiots. It is the holy fool kind of innocence of Prince Myshkin in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot as well as the deadly innocence of the young man Lone in Sturgeon’s The Fabulous Idiot, incorporated into the great work known as More Than Human. Of all humanity’s failings that Arjuna enumerates in such painstaking and painful detail, he counts as the very worst our refusal to embrace our best possibilities and so to live as gods.

The second term we would like to define is quenge, the most quintessential part of a whale’s true nature. Arjuna himself coined the word to represent a nearly ineffable cetacean sensibility and prowess. We would like to explain this strange word, though of course it remains inexplicable. One might as well try to describe a magnificent city on a hill, bright with sunlit cathedrals and great spires, to a band of cave-dwellers. The best course for anyone wishing to know more is to make one’s way into Arjuna’s story. But please do so with an open mind, and even more, with an open heart. Readers who reach the end without having any idea of what it is to quenge will have wasted their time – and Arjuna’s.

1

The humans call me Arjuna, after the hero who spoke with the God of Truth, though they cannot say my real name any more than they can say why the starlit sea sings with such a hush, lovely fire or why they themselves are alive.

When I was a young whale unacquainted with human might and madness, I swam with my family through the icy waters near the top of the world – the world they call Earth and we call Ocean. Along the cold currents we hunted char and salmon and other fishes that schooled in never-ending silvery streams; along our fiery blood we sought ecstasies of creation even as we listened for the great and singular Song that sounds within all things. Sometimes, we gave voice to the deep, unutterable mysteries bound up in the chords of this song; more often we told tales of the glories of our Old Ones or the adventures of the newborn babies just beginning to speak. We held midnight feasts beneath the pink and emerald sprays of light raining down from the Aurora Borealis. During the long, long days of summer, we dove beneath the icebergs and we mated and played and loved and dreamed.

We quenged. Guided by our true nature, which always knows the intention of life and the way home, we followed the ocean’s song wherever it called us, listening always for its source. Great journeys we made! One fine day might find us visiting with the Old Ones in the turquoise swells of the Caribbean ten thousand years ago while on the next day we might wend our way along the arc of the Aurora and swim through ages yet to be up to the stars. We delved the deeps of oceans on worlds without number, daring each other to move ever further outward and inward beyond the limits of space and time. Down through unknown seas we plunged into the melodies of songs sung again and again since the world’s beginning – and into the souls of the stories that their singers poured forth with so much delight. Who could escape from the account of how Mother Maia fought off a hundred great white sharks in order to protect her children? Who could forget the epic of Aldebaran the Great’s circumnavigation of the globe in search of the perfect color of crimsong with which to paint his great tone poem? Who could resist the urge to become both bard and hero of one’s own story? Why else are we here? Are not our lives the very songs that sing the universe into creation?

Many of our best adventures came through dreams or revelations or even the babblings of babes still drinking milk; the worst came out of places so dark and disturbing that few wished ever to go there. It seemed that no whale could ever conceive them. Once, while we were making our way across the nearly infinite seas of Agathange east of earth, I nearly choked on reddened waters and caught a glimpse of a blue god and masses of belligerents slaughtering each other. Another time, on Tiralee, I learned of an eternal quest to find a golden conch shell said to hold entire constellations and oceans inside. I trembled at the vivacity of such visions, for I experienced them simultaneously as impossible and too real, as familiar and utterly strange.

How terrified I was at first of these wild wanderings! How confused, how desperate, how consumed! My mother, though, sleek and black and white and beautiful, swam always beside me with powerful, rhythmic strokes that told of the faith of her great, bottomless heart. She reassured me with murmurs of maternal encouragements as well as with clear, cool logic: was not water, she asked me, the unitive substance which ripples with the shimmering interconnectedness of all things? Was not I, myself, made of water, as was she and my uncles and my ancestors? How could I ever be separate from the sea which had formed me or fail to find my way home? Could I not hear, always, within my own heart the ringing of life’s great song?

Yes, I told her, emboldened by a growing fearlessness, yes, yes I could! Her love, onstreaming like the strongest of currents, filled me with joy. And so I quenged through the world and through the eternal musics which gave it form, moving always and ever deeper and deeper. The water flowed through my skin, and I flowed through the water, and the ocean and I were as one.

I do not remember my conception. Humans die in worry of what will become of them after the worms have eaten their bodies and they are gone; we whales live in wonder of what we were before we came to be. What we were is what we are and always will be: we are salt and seaweed, haddock and diatom and grains of sand glimmering among the fronds of red and purple coral. The ocean forms us out of itself, and each drop of water – each molecule – reverberates with an indestructible consciousness. As we quicken and grow within our mothers’ wombs, we gradually come into full consciousness of our indestructible selves and of the way we are both a tiny part and the entirety of the universe. And then one day, we realize that we are awake and aware – aware that there never could have been a time in which we did not exist.

This happened to me. After some months of life, I awakened to the thunder of my mother’s heart beating out a reassuring rhythm even as it beat into my veins the blood that we both shared. A human might think that I therefore woke up in a drumlike darkness, but it was not so. Everywhere – blazing through the salty amniotic waters and glimmering through my own tiny heart – there was light. Our Old Ones call this phenomenon the brilliance of sound. Do not light and sound emanate from the same essential source? Are they not both experienced within the tissues of our minds as reflections of the forms of the manifold world? Are there not many ways to see? Yes, yes, the fiery splendor of sound and the music of light! To see the world in all its astonishing perfection through waves and echoes of pure vivid sonance – yes, yes, yes!

From nearly the beginning, my mother spoke to me. Mostly, she duplicated the clicks by which she made out the icebergs and shoals, sharks and salmon: all the things of the ocean that a whale needed to perceive. In this way, she made sound pictures for me to see. Long before my birth, I knew the turnings and twisting of the coastlines of the world’s northernmost continents; I knew the rasp of ice and the raucousness of rock and the much softer sounds of snow. The dense, gelid winter sea seemed tinted with hues of tanglow and bluetone, while in the summer the waters came alive with the peals of a color I call glorre.

Sometimes, my mother spoke to me in simple baby speech, forming the basic utterances upon which more mature language would build. She told me simple stories and explained the intricacies of life outside the womb in a way that I could understand. I could not, of course, speak back for I had no air within my lungs and so could not make a single sound within my flute. I listened, though, as my mother told me of the cold of the water outside her that I could not feel and of the stars’ luster that I could not see. I learned the names of my family whom I would soon meet: my aunts Chara and Mira, my uncles Dheneb and Alnitak, my sister Turais and my cousins – and my grandmother, head of our family, whom a young whale such as I would never think to address by name.

When my mind ached with too much knowledge and I grew tired, my mother sang me to sleep with lullabies. When I awakened from dark dreams with a rumbling dread that I would be unable to face life’s difficulties, my mother told me the one thing that every whale must know, something more important than even the Song of Life and the ocean itself: that I had been conceived in love and my mother’s love would always fill my heart – and that no matter how far I swam or how much life hurt me, I would never be alone.

On the day of my birth, my mother instructed me not to breathe until Chara and Mira swam under me and buoyed me up to the surface. I came quickly, tail first, propelled out of my mother’s warm body through a cloud of blood and fear. The shock of the icy water pierced straight through me with a thrilling pain. I nearly gasped in anguish, and so I nearly breathed water and drowned. Mira and Chara, though, as promised pressed their heads beneath my belly and pushed me upward. Light blinded me: not the scintillation of roaring winds but rather the incandescence of the sun impossible to behold. It burned my eyes even as it warmed me in tingles that danced along my skin. The water broke and gave way to the thinness of the atmosphere. In astonishment, I drew my first breath. With my lungs thus filled with air, through my tender, untried flute, I spoke my first baby words in a torrent of squeaks and chirps that I could not contain. What did I say? What should a newborn whale say to the being who had carried and nourished him for so long? Thank you, Mother, for my life and for your love – it is good to be alive.

And so I tasted the sea and drank in the wonder of the world. Everything seemed fascinating and beautiful: the blueness of the sea ice and the shining red bellies of the char that my family hunted; the jewel-like diatoms and the starfish and the joyous songs of the humpbacks that sounded from out of deeps. All was new to me, and all was a marvel and a delight. I wanted to go on swimming through this paradise forever.

How deliciously the days passed as the ocean turned beneath the sun and through the seasons! With my mother ever near, I fattened first on her milk and then on the fish that she taught me to catch for myself. My mind grew nearly as quickly as my body. So much I needed to learn! The sea’s currents had to be studied and the migrations of the salmon memorized. My uncle Alnitak, greatest of our clan’s astronomers, taught me celestial navigation. From Mira I gained the first glimmerings of musical theory and practice, while my older sister Turais shared with me her love of poetics. My mother impressed upon me the vital necessity of the Golden Rule, less through words and songs than through her compassion and her generosity of spirit. As well, she guided me through the maelstrom of the many Egregious Fallacies of Thought and the related Fundamental Philosophical Errors. It took entire years and many pains for her to nurture within me a zest for the arts of being: plexure, zanshin, and shih. Once or twice, in the most tentative and fleeting of ways, I managed to speak of the nature of art itself with the Old Ones.

It was my grandmother, however, who held the greatest responsibility for teaching me about the Song of Life. I must, she told me, quenge deep within myself, down through the dazzling darkness into spaces that can contain the entire universe as a blue whale’s mouth contains a drop of water. As I grew stronger and swifter, I must make of myself a song of glory that found resonance with the song of the sea – and thus become a part of it. At least for a few magical moments, I must quenge with the gods. Was this not the calling of any adult orca? And so I must learn to sing with as great a prowess as I applied to swimming and hunting; only then would my grandmother and my other elders deem me to be a full adult. And only then would I be allowed to mate and make children of my own.

Of what, though, was I to sing? Over many turnings of light and dark, sunshine and snow, I considered the necessities of this composition. My rhapsody, as we call the songs of ourselves, must attain to the uniqueness and perfection of a single snowflake while simultaneously ringing with all the memories of the ocean out of which the snowflake had formed. It must tell of the past of the whole world and of the destiny of the teller.

What, I wondered, would be my destiny? In what way was I unique? Although I could not say, I gained a whisper of an answer to these questions from a prophecy that my grandmother made at my birth: that either I would die young or I would add something new to the Song, something marvelous and strange that had never been heard in all the long ages of our people.

From out of the humans’ oldest poem, these words echo through humanity’s much shorter ages – words that curiously accord with my grandmother’s instructions to me:

You are what your deep, driving desire is

As your desire is, so is your will;

As your will is, so is your deed;

As your deed is, so is your destiny.

Such deeds I wanted to do! – but what deeds? I did not know. Impossible notions came to me. I would journey to the yearly gatherings of the sperm whales, and I would coax these deep gods to reveal all their wisdom. I would crack apart icebergs with a shout from my lungs; I would put the Aurora’s fire into the mouths of the great, mute sharks, and I would teach the starfish to sing.

First, however, I had to apprehend my deepest desire. For many years, I applied myself to this task. I meditated, and I sang, and I grew ever vaster and more powerful, fed in my body by the sea’s fishes and in my soul through my family’s heartenings. I attained my full form, larger even than that of mighty Alnitak. My blood thundered with wild lightnings, and my testes burned with seed, and I dreamed of finding a lovely, young she-orca with whom to mate.

In this season of my discontent, in a time of hunger when the fish were few, there occurred three portents that changed my life. The first of these the humans would regard as a cliché – as wearisome as the slaughters that make up most of their histories. To me, however, the news that my cousin Haedi brought from out of vernal mists one day shocked me with its signal import. She swam up to my grandmother and told of a white bear standing on an ice floe far from the pack ice from which this tiny, floating island had splintered. Our whole family moved off south in order to witness this unheard-of misfortune. Turais’s newborn, little Porrima, remarked that she had never seen a bear.

Long before our eyes could make out this king of land animals, we sighted him with our sonar. How hopeless the situation of this great beast seemed! He made a pitiful figure, a smear of fur atop a bit of ice, forlorn and alone against the churning, gray swells of the sea.

My uncle Alnitak, long and powerful, always so precise with distances, seemed to point his notched dorsal fin at the bear as he said, ‘He could swim back to the ice if he dared – if he had the strength, it is barely possible that he might make it.’

We swam a little closer, our sides nearly touching each other’s, at one in our breath and in our thoughts. Then we dove in a coordinated flow of black and white beneath the surface, closer to the bear and his icy island. My mother zanged the bear with her sonar. This sense did not work very well on objects outside the water, but the clicks my mother made were powerful enough to pierce the bear’s fur, skin, and muscles and to reflect back through the water as images that we all shared.

‘Very well, then,’ my aunt Mira said, in her sad, plaintive voice. ‘The bear has starved and is much too weak to swim so many miles back to the ice.’

What else was there to say? Either the bear would die from the belly-gnawing ache of hunger or he would venture into the water and drown – or find his end in the feeding frenzy of a shark or between the jaws of one of the Others. At this, my grandmother turned back towards our usual fishing lanes. As she often said, each of us has a single destiny.

That might have been the end of the matter had I not chanced to recall a story told to me by Dheneb, who had once spoken with one of the Others. Apparently, when stalking seals, the ice bears were clever enough to cover their black noses with their white paws so that the seals did not detect them creeping forward across the snow fields. Why, I wondered, must such a cunning creature perish so ignominiously just because the ice had mysteriously melted around him?

I determined that he should not die this way. An impulse sounded from within me and swelled like a bubble rising up through the water. I said, ‘Why don’t we push the bear’s island back to the pack ice?’

For a few moments no one spoke. Then Chara flicked her powerful flukes and said to me, ‘What a strange idea! You have always had such strange schemes and dreams!’

‘Thank you,’ I replied. ‘You are complimenting me aren’t you?’

‘Can you not hear in my voice the overtones of my appreciation for your innovatedness of thought?’

‘Sometimes I can, Aunt.’

‘If you listened hard enough at the interstices of my words, you would never doubt how much I value the freshness of your spirit.’

‘Thank you,’ I said again.

‘I value it, as we all do, almost as much as I cherish your compassion – compassion for a bear!’

I zanged the bear with my sonar, and I heard the quickened heart beats that betrayed his fear. Did he sense my family’s holding a conference beneath the waters near his island? What, I wondered, could the bear be thinking?

‘How often,’ I said to Chara, ‘has Grandmother averred that we must have compassion for all things?’

‘And we do! We do!’ she called out. ‘We sing to the diatoms and have family-feeling for the broken shells of the mollusks – even for the bubbles of oxygen in the water that long in their innermost part to be incorporated once again into an inspired young whale such as you who exalts the beauty of compassion.’

Alnitak, less loquacious than Chara, beat his flukes through the sun-dappled water and said simply, ‘I would relish the novelty and satisfaction of saving this bear, but it is too far for us to swim right now. Are we not, ourselves, weak with hunger?’

This was true. Days and days had it been since any of us had eaten! Where had the fish gone? No one could say. We all knew, however, that huge, lovely Grandmother had grown much too thin and my sister Turais had nearly lost her milk and could barely feed the insatiable little Porrima. And Mira, my melancholy aunt, worried about her child Kajam. If our luck did not improve, very soon Kajam would begin to starve along with the rest of us and would likely come down with one of the fevers that had carried off Mira’s first born to the other side of the sea. Her second born had died of a peculiar stomach obstruction, while her third had been born with a deformed tongue and jaw, which had made it impossible for the child to eat. Poor Mira now invested her hope for the future in the young and frail Kajam.

‘All right,’ I finally said, out of frustration, ‘then I will push the bear myself to the pack ice. Perhaps I will encounter fish along the way and return to lead you to them.’

Alarmed at the earnestness in my voice, my mother Rana swam up to me. Her streamlined form, nearly perfect in proportion, flowed through the water along with her concerned words: ‘There is much bravura in what you propose, but also the folly of misplaced pride. This cannot be the great deed you wish to do.’

Chara’s second daughter Talitha, who was only three years old and didn’t know any better, gave voice to one of the usually unvoiced principles by which we live: ‘But you cannot leave your family, cousin Arjuna!’

She loved me a great deal, tiny Talitha did. No words could I find for her. I did not really want to leave her.

We concluded our conference with a decision that I should remain with everyone else. Again my grandmother turned to abandon the bear to the tender mercies of the sea.

‘Wait!’ I cried out. A wild, wild idea rose out of the unknown part of me with all the shock of a tidal wave. ‘Why don’t we eat the bear?’

For a whale, the sea can never be completely quiet, yet I swear that for a moment all sound died into a vast silence. I might as well have suggested eating Grandmother.

Talitha again spoke of the obvious, something my elders knew that I knew very well: ‘But we cannot eat a bear! That would break the First Covenant!’

She went on to recount one of the most important lessons that she had learned: how long ago the orcas had split into two kindreds, one which ate only fish while the other hunted seals and bears and almost any animal made of warm blood and red meat. These Others, who looked much the same as any orca of my clan, almost never mingled with us. We had promised to leave each other alone and never to interfere with the different ways by which we made our livings. Even so, we knew each other’s stories and songs. If we killed the bear, the sea itself would sing of our desperate act, and the Others would eventually learn of how we had broken our covenant with them.