Полная версия

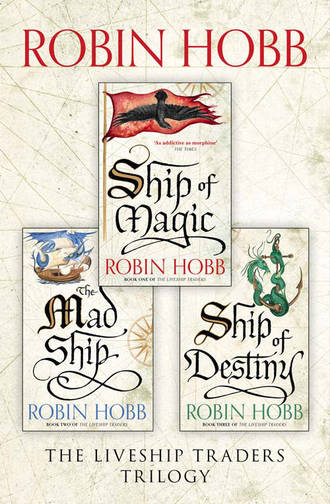

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

‘I see,’ he said, and she was sure that he did. He thanked her and then followed Keffria from the room. Malta and Delo, heads together, followed them. Malta’s pent frustration showed in her flared nostrils and flat lips. Clearly she had expected to get Cerwin alone, or at least in no more than the company of his sister. To what end? Probably the girl herself did not know.

Possibly that was the most frightening thing about all this; that Malta had flung herself into it so aggressively with so little knowledge of the consequences.

And whose fault was that, Ronica was forced to ask herself as she watched them go. The children had been growing up in her household. She had seen them often, at table, underfoot, in the gardens. And yet they had been, always, the children. Not tomorrow’s adults, not small people growing towards what they must someday be, but the children. Selden. Where was Selden, at this moment, what was he doing? Probably with Nana, probably with his tutor, supervised and secure. But that was all she knew of him. A moment of panic washed over her. There was so little time, it might even now be too late to shape them. Look at her own daughters. Keffria, who only wanted someone to tell her what to do, and Althea, who only desired that she do her own will always.

She thought of the numbers on her ledgers, that no act of mere will could change. She thought of the debt she owed the Festrews of the Rain Wilds. Blood or gold, that debt was owed. In a sudden wrenching of her perceptions, it was not her problem. It was Selden’s and it was Malta’s, for were not they the blood that might pay the debt? And she had taught them nothing. Nothing.

‘Mistress? Are you all right?’

She lifted her eyes to Rache. The woman had entered, gathered up the coffee things on a tray, then come to stand next to where her mistress stared black-eyed off into the distance. This woman, a servant-slave in her own house, entrusted with the teaching of her grand-daughter. A woman she hardly knew at all. What did her mere presence in the household teach Malta? That slavery was to be accepted — was that the shape of things to come? What did that say to Malta about what it meant to be a woman in the Bingtown society to come?

‘Sit down,’ she heard herself saying to Rache. ‘We need to talk. About my grand-daughter. And about yourself.’

‘Jamaillia,’ said Vivacia softly.

The word woke him and he lifted his head from the deck where he’d been sleeping in the winter sunlight. The day was clear, neither cool nor warm, and the wind was leisurely. It was that hour of the afternoon designated for him to ‘pay attention to the ship’ as his father so ignorantly put it. He had been sitting on the foredeck mending his trousers and quietly conversing with the figurehead. He did not recall lying down to sleep.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said, rubbing his eyes.

‘Don’t be,’ the ship said simply. ‘Would that I could truly sleep as humans do, turning away from the day and all its cares. That one of us can is a blessing to us both. I only woke you because I thought you would enjoy seeing this. Your grandfather always said that this was the prettiest view of the city, out here where you cannot see any of its faults. There they are. The white spires of Jamaillia.’

He stood, stretched and then stared out across the blue waters. The twin headlands reached out to surround the ship like welcoming arms. The city lined the coast between the steaming mouth of the Warm River and the towering peak of the Satrap’s Mountain. Lovely mansions and estate gardens were separated from one another by belts of trees. On a ridge behind the city rose the towers and spires of the Satrap’s Court. Commonly referred to as the ‘upper city’ it was the heart of Jamaillia City. The capital city that gave its name to the whole Satrapy, centre of civilization, the cradle of all learning and art, glistened in the afternoon sunlight. Green and gold and white, she shone, like a jewel in a setting. Her white spires soared higher than any tree, and so intensely white were they that Wintrow could not look at them without squinting. The spires were banded with gold and the foundations of the buildings were rich green marble from Saden. For a time Wintrow gazed out on it hungrily, seeing for the first time what he had heard of so often.

Some five hundred years ago, most of Jamaillia had burned to the ground. The Satrap of that time had then decreed that his royal city would be rebuilt more magnificently than ever, and that all of the buildings should be of stone so that such a disaster could never befall Jamaillia again. He called together his finest architects and artists and stonemasons, and with their aid and three decades of work, the Court of the Satrap was raised. The next to highest white spire that pointed to the sky denoted the residence of the Satrap. The only spire that soared higher was that of the Satrap’s Temple to Sa, where the Satrap and his Companions worshipped. For a time Wintrow gazed at it, filled with awe and wonder. To be sent to dwell in the monastery that served that temple was the highest honour a priest could aspire to. The library alone filled seventeen chambers, and there were three scribing chambers where twenty priests were constantly employed in renewing or copying the scrolls and books. Wintrow thought of the amassed learning there and awe filled him.

Then bitterness came to darken his soul. So, too, had Cress seemed fair and bright, but it had still been a city of greedy, grasping men. He turned his back on it and slid down to sit flat on the deck. ‘It’s all a trick,’ he observed. ‘All a rotten trick men play on themselves. They get together and they create this beautiful thing and then they stand back and say, “See, we have souls and insight and holiness and joy. We put it all in this building so we don’t have to bother with it in our everyday lives. We can live as stupidly and brutally as we wish, and stamp down any inclination to spirituality or mysticism that we see in our neighbours or ourselves. Having set it in stone, we don’t have to bother with it any more.” It’s a trick men play on themselves. Just one more way we cheat ourselves.’

Vivacia spoke softly. If he had been standing, he might not have heard the words. But he was sitting, his palms flat to her deck, and so they rang through his soul. ‘Perhaps men are a trick Sa played on this world. “All other things I shall make vast and beautiful and true to themselves,” perhaps he said. “Men alone shall be capable of being petty and vicious and self-destructive. And for my cruellest trick of all, I shall put among them men capable of seeing these things in themselves.” Do you suppose that is what Sa did?’

‘That is blasphemy,’ Wintrow said fervently.

‘Is it? Then how do you explain it? All the ugliness and viciousness that is the province of humanity, whence comes it?’

‘Not from Sa. From ignorance of Sa. From separation from Sa. Time and again I have seen children brought to the monastery, boys and girls with no hint as to why they are there. Angry and afraid, many of them, at being sent forth from their homes at such a tender age. Within weeks, they blossom, they open to Sa’s light and glory. In every single child, there is at least a spark of it. Not all stay; some are sent home, not all are suited to a life of service. But all of them are suited to being creations of light and thought and love. All of them.’

‘Mm,’ the ship mused. ‘Wintrow, it is good to hear you speak as yourself again.’

He permitted himself a small, bitter smile and rubbed at the knot of white flesh where his finger had been. It had become a habit, a small one that annoyed him whenever he became aware of it. As now. He folded his hands abruptly and asked, ‘Do I pity myself that much? And is it so obvious to all?’

‘I am probably more sensitized to it than anyone else could be. Still. It is nice to jolt you out of it now and then.’ Vivacia paused. ‘Will you be going ashore, do you think?’

‘I doubt it.’ Wintrow tried to keep the sulkiness from his voice. ‘I haven’t touched shore since I “shamed” my father in Cress.’

‘I know,’ the ship replied needlessly. ‘But, Wintrow, if you do go ashore, be careful of yourself.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t know, exactly. I think it is what your great-great-grandmother would have called a premonition.’

Vivacia sounded so unlike herself that Wintrow stood up and peered over the bow railing at her. She was looking up at him. Every time he thought he had become accustomed to her, there would be a moment like this. The light was unusually clear today, what Wintrow always thought of as an artist’s light. Perhaps that accounted for how luminous she appeared to him. The green of her eyes, the rich gloss of her ebony hair, even her fine-grained skin shone with the best aspects of both polished wood and healthy flesh. She flushed pink to have him stare at her so, and in response to that he felt again the sudden collision of his love for her and his total benightedness as to what she truly was. It rocked him, as it always did. How could he feel this… passion, if he dared to use that word, for a creation of wood and magic? His love had no logical roots he could find… there was no prospect of marriage and children to share, no hunger for physical satiation in one another, there was no long history of shared experience to account for the warmth and intimacy he felt with her. It made no sense.

‘Is it so abhorrent to you?’ she asked him in a whisper.

‘It isn’t you,’ he tried to explain. ‘It is that this feeling is so unnatural. It is like something imposed on me rather than something I truly feel. Like a magic spell,’ he added reluctantly. The followers of Sa did not deny the reality of magic. Wintrow had even seen it done, on rare occasions, small spells to cleanse a wound or spark a fire. But those were acts of a trained will coupled with a gift to have a physical effect. This sudden rush of emotion, triggered, as much as he could determine, solely by prolonged association, seemed to him something else entirely. He liked Vivacia. He knew that, it made sense to him. He had many reasons to like the ship: she was beautiful and kind and sympathetic to him. She had intelligence, and watching her use that intelligence as she built chains of thought was a pleasure. She was like an untrained acolyte, open and willing to any teaching. Who would not like such a being? Logic told him he should like the ship, and he did. But that was separate from the wave of almost painful emotion that would sweep through him at odd moments like this. He would perceive her as more important than home and family, more important than his life at the monastery. At such moments, he could imagine no better end to his life than to fling himself flat upon her decks and be absorbed into her.

But no. The goal of a life lived well was to become one with Sa.

‘You fear that I subvert the place of your god in your heart.’

‘I think that is almost what I fear,’ he agreed with her reluctantly. ‘At the same time, I do not think it is something that you, as Vivacia, impose upon me. I think it has to do with what a liveship is.’ He sighed. ‘If anyone consigned me to this, it was my own family, my great-great-grandmother when she saw fit to commission the building of a liveship. You and I, we are like buds grafted onto a tree. We can grow true to ourselves, but only so much as our roots will allow us.’

The wind gusted up suddenly, as if welcoming the ship into the harbour. Wintrow stood and stretched. He was more aware of the differences in his body these days. He did not think he was getting any taller, but his muscles were definitely harder than they had been. A glimpse in a looking-glass the other day had shown him the roundness gone from his face. Changes. A leaner, fitter body and nine fingers to his hands. But it was still not enough changes to suit his father. When his fever had finally gone down and his hand was healing well, his father had summoned him. Not to tell him he’d been pleased by Wintrow’s show of bravery or even to ask how his hand was. Not even to say he’d noticed his improved skills as a seaman. No. Only to tell him how stupid he had been, that he had had the chance in Cress to win the crew’s approval and be seen as truly a part of them. And he had let it go by.

‘It was a sham,’ he’d told his father. ‘The whole set-up with the bear and the man who won were just a lure. I knew that right away.’

‘I know that!’ his father had declared impatiently. ‘That’s not the point. You didn’t have to win, you idiot. Only to show them you have spunk. You thought to prove your courage by standing silent while Gantry cut off your finger. I know you did, don’t deny it. Instead you only showed yourself as some sort of… religious freak. When they expected guts, you showed yourself a coward. And when any normal man would have cried out and cursed, you behaved like a fanatic. At the rate you’re going, you’ll never win this crew. You’ll never be part of them, let alone a leader they respect. Oh, they may pretend to accept you, but it won’t be real. They’ll just be waiting for you to let your guard down, so they can really put it to you. And you know something? That’s what you’ve earned from them. And damn me if I don’t hope you get it!’

His father’s words still echoed through him. In the long days that had passed since then, he had thought he sensed a grudging acceptance by the crew. Mild, as swift to forgive as he was to take offence, had been most quick to resume a tolerant attitude towards him. But Wintrow could no longer relax and accept it. Sometimes, at night, when he tried to reach for his old meditative states, he could convince himself that the situation was contrived. His father had poisoned his attitude toward the other crew members. His father did not wish to see them accept him; therefore he would see to it, however he could, that Wintrow remained an outcast. And that, he told himself as he painstakingly traced the convoluted logic of such insanity, was why he must never trust completely to the crew’s acceptance and friendship. Because if he did, his father would find some way to turn them against him.

‘Every day,’ he said quietly, ‘it becomes harder for me to know who I am. My father plants doubts and suspicions in me, the coarseness of life aboard this ship accustoms me to casual cruelty amongst my fellows and even you, even the hours I spend with you are shaping me, carrying me away from my priesthood. Toward something else. Something I don’t think I want to be.’

These words were hard for him to speak. They hurt him as much as they hurt her. That was the only thing that let her keep silent.

‘I don’t think I can stand it much longer,’ he warned her. ‘Something will have to give way. And I fear it will be me.’ He met her eyes unflinchingly. ‘I’ve just been living from day to day. Waiting for something or someone else to change the situation.’ His eyes studied her face, looking for a reaction to his next words, ‘I think I need to make a real decision. I believe I need to take action on my own.’

He waited for her to say something, but she could think of no words. What was he hinting he might do? What could the boy do against his father’s dominance?

‘Hey, Wintrow! Lend a hand!’ someone shouted down to the deck.

The call back to drudgery. ‘I have to go,’ he told Vivacia. He took a deep breath. ‘Right or wrong, I’ve come to love you. But —’ He shook his head, suddenly wordless.

‘Wintrow! Now!’

Like a well-trained dog, he sprang to obey. She watched him scamper up the rigging with familiar ease. That facility told as much as his words did of his love for her. He still complained, and often. He still suffered the torments of a divided heart. But when he gave words to his unhappiness they could discuss it and both learn more of one another in the process. He thought now that he could not bear it, but she knew the truth. Inside him was strength, and he would bear up despite unhappiness. Eventually they would be whole, the both of them. All that they needed was time. She had known ever since that first night together that he was truly destined to be aboard her. It was not easy for him to accept. He had struggled long against the idea. But even in his defiant words today, she sensed a pending resolution to that struggle. Her patience would be rewarded.

She looked about the harbour with new eyes. In many ways, Wintrow was absolutely correct about the city’s underlying corruption. Not that she would want to reinforce that with the boy. He needed no help from her to be gloomy. Better for Wintrow that he focus his thoughts on what was clean and good about Jamaillia. The harbour was lovely in the winter sunlight.

She did and yet did not recall it all. Ephron’s memory of it was a man’s view, not a ship’s. He had focused on the docks and merchants awaiting his trade goods, and the architectural wonder of the city above them. Ephron could never have noticed the curling tendrils of filthy water bleeding into the harbour from the city’s sewers. Nor could he have smelt with every pore of his hull the underlying stench of serpent. Her eyes skimmed the placid waters but there was no sight of the cunning, evil creatures. They were below, worming about in the soft mud of the harbour. Some foreboding made her swing her gaze to the section of the harbour where the slavers anchored. Their foul stench came to her in hints on the wind. The smell of serpent was mixed with that of death and faeces. That was where the creatures coiled thickest, over there beneath those miserable ships. Once she was unloaded and refitted for her new trade, she would be anchored alongside them, taking on her own load of misery and despair. Vivacia crossed her arms and held herself. Despite the sunny day, she shivered. Serpents.

Ronica sat in the study that had once been Ephron’s and was now slowly becoming hers. It was in this room that she felt closest to him still, and in this room that she missed him most. In the months since his death, she had gradually cleared away the litter of his life, replacing it with the untidy scattering of her own bits of papers and trifles. Yet Ephron was still there in the bones of the room. The massive desk was far too large for her, and sitting in his chair made her feel like a small child. Oddities and ornaments of his far-ranging voyages characterized this room. A massive sea-washed vertebra from some immense sea creature served as a footstool, while one wall shelf was devoted to carved figurines, seashells, and strange body ornaments from distant folk. It was an odd intimacy to have her ledgers scattered across the polished slab of his desk top, to have her tea cup and discarded knitting draped on the arm of his chair by his fireplace.

As she often did when perplexed, she had come here to think and try to decide what Ephron would have counselled her. She was curled on the divan on the opposite side of the fireplace, her slippers discarded on the floor. She wore a soft woollen robe, well worn from two years’ use. It was as comfortable as her seat. She had built the fire herself, and kindled it and watched it burn through its climax. Now the wood was settling, glowing against itself, and she was relaxed and warm but seemed no closer to an answer of any kind.

She had just decided that Ephron would have shrugged his shoulders and delegated the problem back to her when she heard a tap at the heavy wood-panelled door.

‘Yes?’

She had expected Rache, but it was Keffria who entered. She wore a nightrobe and her heavy hair was braided and coiled as for sleep, but she carried a tray with a steaming pot and heavy mugs on it. Ronica smelled coffee and cinnamon.

‘I had given up on your coming.’

Keffria didn’t directly answer that. ‘I decided that as long as I couldn’t sleep, I might as well be really awake. Coffee?’

‘Actually, that would be good.’

This was the sort of peace they had found, mother and daughter. They talked past one another, asking no questions save regarding food or some other trifle. Keffria and Ronica both avoided anything that might lead to a confrontation. Earlier, when Keffria had not come as invited, Ronica had assumed that was why. Bitterly she had reflected that Kyle had taken both her daughters from her: driven the one away and walled the other up. But now she was here, and Ronica found herself suddenly determined to regain at least something of her daughter. As she took the steaming mug from Keffria, she said, ‘I was impressed by you today. Proud.’

A bitter smile twisted Keffria’s face. ‘Oh, I was too. I single-handedly triumphed in defeating the conniving plot of a sly thirteen year old girl.’ She sat down in her father’s chair, kicked off her slippers and curled her feet up under her. ‘Rather a hollow victory, Mother.’

‘I raised two daughters,’ Ronica pointed out gently. ‘I know how painful victory can be sometimes.’

‘Not over me,’ Keffria said dully. There was self-loathing in her tone as she added, ‘I don’t think I ever gave you and father a sleepless night. I was a model child, never challenging anything you told me, keeping all the rules, and earning the rewards of such virtue. Or so I thought.’

‘You were my easy daughter,’ Ronica conceded. ‘Perhaps because of that, I undervalued you. Overlooked you.’ She shook her head to herself. ‘But in those days, Althea worried me so that I seldom had a moment to think of what was going right…’

Keffria exhaled sharply. ‘And you didn’t know the half of what she was doing! As her sister, I… but in all the years, it hasn’t changed. She still worries us, both of us. When she was a little girl, her wilfulness and naughtiness always made her papa’s favourite. And now that he has gone, she has disappeared, and so managed to capture your heart as well, simply by being absent.’

‘Keffria!’ Ronica rebuked her for the heartless words. Her sister was missing, and all she could be was jealous of Ronica worrying about her? But after a moment, Ronica asked hesitantly, ‘You truly feel that I give no thoughts to you, simply because Althea is gone?’

‘You scarcely speak to me,’ Keffria pointed out. ‘When I muddled the ledger books for what I had inherited, you simply took them back from me and did them yourself. You run the household as if I were not here. When Cerwin appeared on the doorstep today, you charged directly into battle, only sending Rache to tell me about it as an afterthought. Mother, were I to vanish as Althea has, I think the household would only run more smoothly. You are so capable of managing it all.’ She paused and her voice was almost choked as she added, ‘You leave no room for me to matter.’ She hastily lifted her mug and took a long sip of the steaming coffee. She stared deep into the fireplace.

Ronica found herself wordless. She drank from her own mug. She knew she was making excuses when she said, ‘But I was always just waiting for you to take things over from me.’

‘And always so busy holding the reins that you had no time to teach me how. “Here, give me that, it’s easier if I just do it myself.” How many times have you said that to me? Do you know how stupid and helpless it always made me feel?’ The anger in her voice was very old.

‘No,’ Ronica said quietly. ‘I didn’t know that. But I should have. I really should have. And I am sorry, Keffria. Truly sorry.’

Keffria snorted out a sigh. ‘It doesn’t really matter, now. Forget it.’ She shook her head, as if sorting through things she could say to find the words she must. ‘I’m taking charge of Malta,’ she said quietly. She glanced up at her mother as if expecting opposition. Ronica only looked at her. She took a deeper breath. ‘Maybe you doubt that I can do it. I know I doubt it. But I know I’m going to try. And I wanted to ask you… No. I’m sorry, but I have to tell you this. Don’t interfere. No matter how rocky or messy it gets. Don’t try to take it away from me because it’s easier to do it yourself.’

Ronica was aghast. ‘Keffria, I wouldn’t.’

Keffria stared into the fire. ‘Mother, you would. Without even knowing you were, just as you did today. I took what you had set up, and handled it from there. But left to myself, I would not have called Malta down at all. I would have told Cerwin and Delo that she was out or busy or sick, and sent them politely on their way, without giving Malta the chance to simper and flirt.’