Полная версия

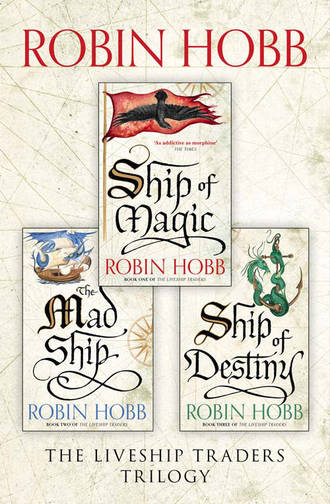

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

The girl was in on it. Althea grasped that instantly, and spurred by her pain, she struck the tavern maid in the face as hard as she could with her left hand. It was not her best punch, but the girl seemed shocked as much as hurt. Clutching at her face, she staggered back with a scream as Althea spun to face the man beside the door. ‘You heartless little bastard!’ the man spat, and swung at her. Althea ducked it and sprang for the door behind him. She managed to pull it partway open. ‘Crimpers!’ she shouted with every bit of breath in her body. A white flash of light knocked her to the floor.

Voices came back first. ‘One from the Tern, the one they’ve been looking for. He was tied up in the beer cellar. One from the Carlyle and these two from the Reaper. Plus it looks like there’s a couple more out the back with some earth scraped over them. Probably hit them too hard. Tough way for a sailor to go.’

There was a shrug in the second voice that replied, ‘Well, tough is true, but we never seem to run out of them.’

She opened her eyes to overturned tables and benches. Her cheek was in a puddle of something; she hoped it was beer. Men’s legs and boots were in front of her face, close enough to step on her. She tipped her head to look up at them. Townsmen wearing heavy leathers against the storm’s chill. She pushed against the floor. On her second try she managed to sit up. The movement set the room to rocking before her.

‘Hey, the boy’s coming round,’ a voice observed. ‘What did you hit Pag’s girl for, you sot?’

‘She was the bait. She’s in on it,’ Althea said slowly. Men. Couldn’t they even see what was right in front of their faces?

‘Maybe, maybe not,’ the man replied judiciously. ‘Can you stand?’

‘I think so.’ She clutched at an overturned chair and managed to get to her feet. She was dizzy and felt like throwing up. She touched the back of her head cautiously, then looked at her red fingers. ‘I’m bleeding,’ she said aloud. No one seemed greatly interested.

‘Your mate’s still in there,’ the man in boots told her. ‘Better get him out of there and back to your ship. Pag’s pretty mad at you for punching his daughter. Didn’t no one ever teach you any manners about women?’

‘Pag’s in on it, too, if it’s going on in his back room and beer cellar,’ Althea pointed out dully.

‘Pag? Pag’s run this tavern for ten years I know about. I wouldn’t be saying such wild things if I were you. It’s your fault all his chairs and tables are busted up, too. You aren’t exactly welcome here any more.’

Althea squeezed her eyes shut and then opened them. The floor seemed to have steadied. ‘I see,’ she told the man. ‘I’ll get Brashen out of here.’ Obviously Nook was their town, and they’d run it as they saw fit. She was lucky the tavern had been full of other sailors who weren’t fond of crimpers. These two townsmen didn’t seem overly upset about how Pag made his extra money. She wondered. If there weren’t a knot of angry sailors still hovering near the fire, would they be letting her and Brashen go even now? She’d better leave while the going was good.

She staggered to the door of the back room and looked in. Brashen was sitting up on the bed, his head bowed into his hands. ‘Brash?’ she croaked.

‘Althea?’ he replied dazedly. He turned toward her voice.

‘It’s Athel!’ she asserted grumpily. ‘And I’m getting damned tired of being teased about my name.’ She reached his side and tugged uselessly at his arm. ‘Come on. We’ve got to get back to the ship.’

‘I’m sick. Something in the beer,’ he groaned. He lifted a hand to the back of his head. ‘And I think I was sapped, too.’

‘Me, too.’ Althea leaned closer to him and lowered her voice. ‘But we’ve got to get out of here while we can. The men outside the door don’t seem too upset about Pag’s crimping. The sooner we’re out of here, the better.’

He caught the idea quickly, for one as bleary as he looked. ‘Give me your shoulder,’ he ordered her, and staggered upright. She took his arm across her shoulders. Either he was too tall or she was too short for it to work properly. It almost felt as if he was deliberately trying to push her down as they staggered out of the back room and then through the tavern to the door. One of the men at the fireside nodded to them gravely, but the two townsmen merely watched them go. Brashen missed a step as they went down the stairs and they both nearly fell into the frozen muck of the street.

Brashen lifted his head to stare into the wind and rain. ‘It’s getting colder.’

‘The rain will turn to sleet tonight,’ Althea predicted sourly.

‘Damn. And the night started out so well.’

She trudged down the street with him leaning heavily on her shoulder. At the corner of a shuttered mercantile store she stopped to get her bearings. The whole town was black as pitch and the cold rain running down her face didn’t help any.

‘Stop a minute, Althea. I’ve got to piss.’

‘Athel,’ she reminded him wearily. His modesty consisted of stumbling two steps away as he fumbled at his pants.

‘Sorry,’ he said gruffly a few moments later.

‘It’s all right,’ she told him tolerantly. ‘You’re still drunk.’

‘Not drunk,’ he insisted. He put a hand on her shoulder again. ‘There was something in the beer, I think. No, I’m sure of it. I’d have probably tasted it, but for the cindin.’

‘You chew cindin?’ Althea asked incredulously. ‘You?’

‘Sometimes,’ Brashen said defensively. ‘Not often. And I haven’t in a long time.’

‘My father always said it’s killed more sailors than bad weather,’ Althea told him sourly. Her head was pounding.

‘Probably,’ Brashen agreed. As they passed beyond the buildings and came to the docks he offered, ‘You should try it sometime, though. Nothing like it for setting a man’s problems aside.’

‘Right.’ He seemed to be getting wobblier. She put her arm around his waist. ‘Not far to go now.’

‘I know. Hey. What happened back there? In the tavern?’

She wanted so badly to be angry then but found she didn’t have the energy. It was almost funny. ‘You nearly got crimped. I’ll tell you about it tomorrow.’

‘Oh.’ A long silence followed. The wind died down for a few breaths. ‘Hey. I was thinking about you earlier. About what you should do. You should go north.’

She shook her head in the darkness. ‘No more slaughter-boats for me after this. Not unless I have to.’

‘No, no. That’s not what I mean. Way north, and west. Up past Chalced, to the Duchies. Up there, the ships are smaller. And they don’t care if you’re a man or a woman, so long as you work hard. That’s what I’ve heard anyway. Up there, women captain ships, and sometimes the whole damned crew are women.’

‘Barbarian women,’ Althea pointed out. ‘They’re more related to the Out Islanders than they are to us, and from what I’ve heard, they spend most of their time trying to kill each other off. Brashen, most of them can’t even read. They get married in front of rocks, Sa help us all.’

‘Witness stones,’ he corrected her.

‘My father used to trade up there, before they had their war,’ she went on doggedly. They were out on the docks now, and the wind suddenly gusted up with an energy that nearly pushed her down. ‘He said,’ she grunted as she kept Brashen to his feet, ‘that they were more barbaric than the Chalcedeans. That half their buildings didn’t even have glass windows.’

‘That’s on the coast,’ he corrected her doggedly. ‘I’ve heard that inland, some of the cities are truly magnificent.’

‘I’d be on the coast,’ she reminded him crankily. ‘Here’s the Reaper. Mind your step.’

The Reaper was tied to the dock, shifting restlessly against her hemp camels as both wind and waves nudged at her. Althea had expected to have a difficult time getting him up the gangplank, but Brashen went up it surprisingly well. Once aboard, he stood clear of her. ‘Well. Get some sleep, boy. We sail early.’

‘Yessir,’ she replied gratefully. She still felt sick and woozy. Now that she was back aboard and so close to her bed, she was even more tired. She turned and trudged away to the hatch. Once below she found some few of the crew still awake and sitting around a dim lantern.

‘What happened to you?’ Reller greeted her.

‘Crimpers,’ she said succinctly. ‘They made a try for Brashen and me. But we got clear of them. They found the hunter off the Tern, too. And a couple of others, I guess.’

‘Sa’s balls!’ the man swore. ‘Was the skipper from the Jolly Gal in on it?’

‘Don’t know,’ she said wearily. ‘But Pag was for sure, and his girl. The beer was drugged. I’ll never go in his tavern again.’

‘Damn. No wonder Jord’s sleeping so sound, he got the dose that was meant for you. Well, I’m heading over to the Tern, hear what that hunter has to say,’ Reller declared.

‘Me, too.’

Like magic, the men who were even partially awake rose and flocked off to hear the gossip. Althea hoped the tale would be well embroidered for them. For herself, she wanted only her hammock and to be under sail again.

It took him four tries to light the lantern. When the wick finally burned, he lowered the glass carefully and sat down on his bunk. After a moment he rose, to go to the small looking-glass fastened to the wall. He pulled down his lower lip and looked at it. Damn. He’d be lucky if the burns didn’t ulcerate. He’d all but forgotten that aspect of cindin. He sat down heavily on his bunk again and began to peel his coat off. It was then he realized the left cuff of his coat was soaked with blood as well as rain. He stared at it for a time, then gingerly felt the back of his head. No. A lump, but no blood. The blood wasn’t his. He patted his fingers against the patch of it. Still wet, still red. Althea? he wondered groggily. Whatever they had put in the beer was still fogging his brain. Althea, yes. Hadn’t she told him she’d been hit on the head? Damn her, why hadn’t she said she was bleeding? With the sigh of a deeply wronged man, he pulled his coat on again and went back out into the storm.

The forecastle was as dark and smelly as he remembered it. He shook two men awake before he found one coherent enough to point out her bunking spot. It was up in a corner a rat wouldn’t have room to turn around in. He groped his way there by the stub of a candle and then shook her awake despite curses and protests. ‘Come to my cabin, boy, and get your head stitched and stop your snivelling,’ he ordered her. ‘I won’t have you lying abed and useless for a week with a fever. Lively, now. I haven’t all night.’

He tried to look irritable and not anxious as she followed him out of the hold and up onto the deck and then into his cabin. Even in the candle’s dimness, he could see how pale she was, and how her hair was crusted with blood. As she followed him into his tiny chamber, he barked at her, ‘Shut the door! I don’t care to have the whole night’s storm blow through here.’ She complied with a sort of leaden obedience. The moment it was closed he sprang past her to latch it. He turned, seized her by the shoulders, and resisted the urge to shake her. Instead he sat her firmly on his bunk. ‘What is the matter with you?’ he hissed as he hung his coat on the peg. ‘Why didn’t you tell me you were hurt?’

She had, he knew, and half-expected that to be her reply. Instead she just raised a hand to her head and said vaguely, ‘I was just so tired…’

He cursed the small confines of his room as he stepped over her feet to reach the medicine chest. He opened it and picked through it, and then tossed his selections on the bunk beside her. He moved the lantern a bit closer; it was still too dim to see clearly. She winced as his fingers walked over her scalp, trying to part her thick dark hair and find the source of all the blood. His fingers were wet with it; it was still bleeding sluggishly. Well, scalp wounds always bled a lot. He knew that, it should not worry him. But it did, as did the unfocused look to her eyes.

‘I’m going to have to cut some of your hair away,’ he warned her, expecting a protest.

‘If you must.’

He looked at her more closely. ‘How many times did you get hit?’

‘Twice. I think.’

‘Tell me about it. Tell me everything you can remember about what happened tonight.’

And so she spoke, in drifting sentences, while he used scissors to cut her hair close to the scalp near the wound. Her story did not make him proud of his quick wits. Put together with what he knew of the evening, it was clear that both he and Althea had been targeted to fill out the Jolly Gal’s crew. It was only the sheerest luck that he was not chained up in her hold even now.

The split he bared in her scalp was as long as his little finger and gaping open from the pull of her queue. Even after he cut the hair around it to short stubble and cleared the clotted strands away, it still oozed blood. He blotted it away with a rag. ‘I’ll need to sew this shut,’ he told her. He tried to push away both the wooziness from whatever had been in his beer and his queasiness at the thought of pushing a needle through her scalp. Luckily Althea seemed even more beclouded than he was. Whatever the crimpers had put in the beer worked well.

By the lantern’s shifting yellow light, he threaded a fine strand of gut through a curved needle. It felt tiny in his calloused fingers, and slippery. Well, it couldn’t be that much different from patching clothes and sewing canvas, could it? He’d done that for years. ‘Sit still,’ he told her needlessly. Gingerly he set the point of the needle to her scalp. He’d have to push it in shallowly to make it come up again. He put gentle pressure on the needle. Instead of piercing her skin, her scalp slid on her skull. He couldn’t get the needle to slide through.

A bit more pressure and Althea yelled, ‘Wah!’ and suddenly batted his hand away. ‘What are you doing?’ she demanded angrily, turning to glare up at him.

‘I told you. I’ve got to stitch this shut.’

‘Oh.’ A pause. ‘I wasn’t listening.’ She rubbed at her eyes, then reached back to touch her own scalp cautiously. ‘I suppose you do have to close it,’ she said ruefully. She squeezed her eyes shut, then opened them again. ‘I wish I could either pass out or wake up,’ she said woefully. ‘I just feel foggy. I hate it.’

‘Let me see what I have in here,’ he suggested. He knelt on one knee to rummage through the ship’s stores of medicines. ‘This stuff hasn’t been replenished in years,’ he grumbled to himself as Althea peered past his shoulder. ‘Half the containers are empty, the herbs that should be green or brown are grey, and some of the other stuff smells like mould.’

‘Maybe it’s supposed to smell like mould?’ Althea suggested.

‘I don’t know,’ he muttered.

‘Let me look. I used to restock Vivacia’s medicines when we got to town.’ She leaned against him to reach the chest in the small space between the bunk and the wall. She inspected a few bottles, holding them up to the lamplight and then setting them aside. She opened one small pot, wrinkled her nose in distaste at the strong odour, and capped it again. ‘There’s nothing useful in there,’ she decided, and sat back on the bunk. ‘I’ll hold it closed and you just stitch it. I’ll try to sit still.’

‘Just a minute,’ Brashen said grudgingly. He had saved part of the plug of cindin. Not a very large part, just a bit to give him something to look forward to on a bad day. He took it out of his coat pocket and brushed lint off it. He showed it to Althea and then carefully broke it in two pieces. ‘Cindin. It should wake you up a bit, and make you feel better. You do it like this.’ He tucked it into his lower lip, packed it down with his tongue. The familiar bitterness spread through his mouth. If it hadn’t been for the taste of the cindin, he thought ruefully, he might have tasted the drug in his beer. He pushed that aside as a useless thought and nudged the cindin away from the earlier sore.

‘It’ll taste very bitter at first,’ he warned her. ‘That’s the wormwood in it. Gets your juices going.’

She looked very dubious as she tucked it into her lip. She made a wry face and then sat meeting his eyes, waiting. After a moment she asked, ‘Is it supposed to burn?’

‘This is pretty strong stuff,’ he admitted. ‘Shift it around in your lip. Don’t leave it in one place too long.’ He watched the expression on her face slowly change, and felt an answering grin spread over his own. ‘Pretty good, huh?’

She gave a low laugh. ‘Fast, too.’

‘Starts fast, ends fast. I never really saw any harm to it, as long as a man had finished before he came on watch.’

He watched her awkwardly move the plug in her lip. ‘My father said that men used it when they should have been sleeping instead. Then they come on watch all used up. And if they were still on it when they were working, they’d be too confident, and take unneeded risks.’ Her voice trailed off. ‘“Risk-takers endanger everyone”, he always said.’

‘Yes. I remember,’ Brashen agreed gravely. ‘I never used cindin aboard the Vivacia, Althea. I respected your father too much.’

For a moment silence held, then she sighed. ‘Let’s do this,’ she suggested.

‘Right,’ he agreed. He took up the needle and thread again. She followed it with her eyes. Maybe he’d made her too alert. ‘There’s no room in here to work,’ he complained. ‘Here. Lie down on the bunk and turn your head. Good.’ He crouched down on the floor beside the bunk. This was better, he could almost see what he was doing. He dabbed away the sluggishly welling blood and picked out a few stray hairs. ‘Now hold the gash shut. No, your fingers are in the way. Here. Like this.’ He arranged her hands, and it was no accident that one of her wrists was mostly over her eyes. ‘I’ll try to be quick.’

‘Be careful instead,’ she warned him. ‘And don’t stitch it too tight. Just pull the edges together as evenly as you can, but not so they hump up.’

‘I’ll try. I’ve never done this before, you know. But I’ve watched it done more than once.’

She moved the plug of cindin in her lip, and he remembered to shift his own. He winced as it touched a sore from earlier in the evening. He saw her jaws clench and he began. He tried not to think of the pain he inflicted, only of doing a good job. He finally got the needle to pierce her scalp. He had to hold the skin firmly to her skull as he brought the tip of the curved needle up on the other side of the cut. Drawing the thread through was the worst. It made a tiny ripping noise as it slipped through, very unnerving to him. She set her teeth and shuddered to each stitch, but did not cry out.

When it was finally done, he tied the last knot and then snipped away the extra thread.

‘There,’ he told her, and tossed the needle aside. ‘Let go, now. Let me see how I did.’

She dropped her hands to the bed. Sweat misted her face. He studied the gash critically. His work was not wonderful, but it was holding the flesh closed. He nodded his satisfaction to her.

‘Thanks.’ She spoke softly.

‘Thank you.’ He finally said the words. ‘I owe you. But for you, I’d be in the hold of the Jolly Gal by now.’ He bent his head and kissed her cheek. Then her arm came up around his neck and she turned her mouth to the kiss. He lost his balance and caught himself awkwardly with one hand on the edge of the bunk, but did not break the kiss. She tasted of the cindin they were sharing. Her hand grasped the back of his neck gently and that touch was as stimulating as the kiss. It had been so long since anyone had touched him with gentleness.

She finally broke the kiss, moving her mouth aside from his. He leaned back from her. ‘Well,’ he said awkwardly. He took a breath. ‘Let’s get a bandage on your head.’

She nodded at him slowly.

He took up a strip of cloth and leaned over her again. ‘It’s the cindin, you know,’ he said abruptly.

She moved it in her lip. ‘Probably. And I don’t care if it is.’ Narrow as the bunk was, she still managed to edge over in it. Invitingly. She set her hand to his side and heat seemed to radiate out from it. A shiver stood his hair up in gooseflesh. The hand urged him forward.

He made a low sound in his throat and tried one last time. ‘This isn’t a good idea. It’s not safe.’

‘Nothing is,’ she told him, almost sadly.

His fingers were awkward on the laces of her shirt, and even after she shrugged out of it, there was a wrapping about her chest. He unwound it to free her small breasts and kiss them. Thin, she was so thin, and she tasted of the salt water, oakum and even the oil that was their cargo. But she was warm and willing and female, and he crammed himself into the too-narrow, too-short bunk to be with her. It was likely the cindin that made her dark eyes bottomless, he tried to tell himself. Startling it was that such a sharp-tongued girl would have a mouth so soft and pliant. Even when she set her teeth to the flesh of his shoulder to still her wordless cries, the pain was sweet. ‘Althea,’ he said softly into her hair, between the second and third times. ‘Althea Vestrit.’ He named not just the girl but the whole realm of sensation she had wakened in him.

Brash. Brashen Trell. Some small part of her could not believe she was doing this with Brashen Trell. Not this. Some small, sarcastic observer watched incredulously as she indulged her every impulse with his body. He was the worst possible choice for this. Then, too late to worry about it, she told herself, and pulled him even deeper inside her. She strained against him. It made no sense, but she could not find the part of her that cared about such things. Always, other than that first time, she’d had the sense to keep this sort of thing impersonal. Now not only was she giving in to herself and him with an abandonment that shocked her, but she was doing this with someone she had known for years. And not just once, no. He had scarcely collapsed upon her the first time before she was urging him to begin again. She was like a starving woman suddenly confronted with a banquet. The heat in her was strong, and she wondered if that were the cindin. But just as great was the sudden need she was admitting for this close human contact, the touching and sharing and holding. At one point she felt tears sting her eyes and a sob shake her. She stifled it against his shoulder, almost afraid of the strength of the loneliness and fears that this coupling seemed to be erasing. For so long she had been strong; she could not bear to display her weakness like this to anyone, let alone to someone who actually knew who she was. So she clutched him fiercely and let him believe it was part of her passion.

She did not want to think. Not now. Now she just wanted to take what she could get, for herself. She ran her hands over the hard muscles of his arms and back. In the centre of his chest was a thick patch of curly hair. Elsewhere on his chest and belly there was black stubble, the hair chafed away by the coarse fabric of his clothes and the ship’s constant motion. Over and over again he kissed her, as if he could not get enough of it. His mouth tasted of cindin, and when he kissed her breasts, she felt the hot sting of the drug on her nipples. She slipped her hand down between their bodies, felt the hard slickness of him as he slid in and out of her. A moment later she clapped her hand over his mouth to muffle his cry as he thrust into her and then held them both teetering on the edge of for ever.

For a time she thought of nothing. Then from somewhere else, she abruptly came back to the narrow sweaty bunk and his crushing weight upon her and her hair caught under his splayed hand. Her feet were cold, she realized. And she had a cramp in the small of her back. She heaved under him. ‘Let me up,’ she said quietly, and when he did not move at first, ‘Brashen, you’re squashing me. Get off!’

He shifted and she managed to sit up. He edged over on the bunk so that she was sitting in the curl of his prone body. He looked up at her, not quite smiling. He lifted a hand, and with a finger traced a circle around one of her breasts. She shivered. With a tenderness that horrified her, he drew the sole blanket up to drape her shoulders. ‘Althea,’ he began.