Полная версия

Secret of the Indian

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

1 A Shocking Homecoming

2 Modest Heroes

3 How It All Started

4 Dead in the Night

5 Patrick Goes Back

6 A New Insider

7 Patrick in Boone-land

8 A Heart Stops Beating

9 Tasmin Drives a Bargain

10 A Rough Ride

11 Ruby Lou

12 Caught Red-Handed

13 Mr Johnson Smells a Rat

14 A Strange Yellow Sky

15 Interrogation

16 Panic

17 The Big Blow

18 Red Satin

Epilogue at a Wedding

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

For Sheila Watson – sine qua non

1

A Shocking Homecoming

When Omri’s parents drove home from their party, his mother got out in front of the house while his father drove round the side to put the car away. The front-door key was on the same key ring with the car key, so his mother came up the steps and rang the bell. She expected the baby-sitter to answer.

There was a lengthy pause and then the door opened and there was Omri, with Patrick just behind him. The light was behind him too, so she didn’t see him clearly at first.

“Good heavens, are you boys still up? You should have been in bed hours ag—”

Then she stopped. Her mouth fell open and her face drained of colour.

“Omri! What – what – what’s happened to your face?”

She could hardly speak properly, and that was when Omri realized that he wasn’t going to get away with it so easily this time. This time he was either going to have to lie like mad or he was going to have to tell far more than he had ever intended about the Indian, the key, the cupboard and all the rest of it.

He and Patrick had talked about it, frantically, before his parents returned.

“How are you going to explain the burn on your head?” Patrick asked.

“I don’t know. That’s the one thing I can’t explain.”

“No it’s not. What about all the little bullet-holes and stuff in your parents’ bedroom?”

Omri’s face was furrowed, even though every time he frowned, it hurt his burn.

“Maybe they won’t notice. They both need glasses. Do you think we should clear everything up in there?”

Patrick had said, “No, better leave it. After all, they’ve got to know about the burglars. Maybe in all the fuss about that, they won’t notice your face and a few other things.”

“How shall we explain how we got rid of them – the burglars I mean?”

“We could just say we burst in through the bathroom and scared them away.”

Omri had grinned lopsidedly. “That makes us out to be heroes.”

“So what’s so bad about that? Anyway it’s better than telling about them.” Patrick, who had once been quite keen to tell ‘about them’, now realized perfectly clearly that this was about the worst thing that could happen.

“But where is the wretched baby-sitter? Why didn’t she come? How dare she not turn up when she promised?”

Omri’s father was stamping up and down the living-room in a fury. His mother, meanwhile, was holding Omri round the shoulders. He could feel her hand cold and shaking right through his shirt. After her first shocked outburst when she’d come home and seen him, she’d said very little. His father, on the other hand, couldn’t seem to stop talking.

“You can’t depend on anyone! Where the hell are the police, I called them hours ago!” (It was five minutes, in fact.) “One would think we lived on some remote island instead of in the biggest city in the world! You pay their damned salaries and when you need the police, they’re never there, never!”

He paused in his pacing and gazed round wildly. The boys had put the television back and there wasn’t much disorder to see in this room. Upstairs, they knew, chaos and endless unanswerable questions waited.

“Tell me again what happened.”

“There were burglars, Dad,” Omri said patiently. (This part was safe enough.) “Three of them. They came in through that window—”

“How many times have I said we ought to have locks fitted? Idiot that I am! – for the sake of a few lousy pounds – go on, go on…”

“Well, I was asleep in here—”

“In the living-room? Why?”

“I – er – I just was. And I woke up, and saw them, but they didn’t see me. So I nipped upstairs, and—”

His father, desperate to hear the story, was still too agitated to listen to more than a sentence of it without interrupting.

“And where were you, Patrick?”

Patrick glanced at Omri for guidance. Omri shrugged very slightly with his eyebrows. He didn’t know himself how much to say and what to keep quiet about.

“I was – in Omri’s room. Asleep.”

“All right, all right! Then what?”

“Er – well, Omri came up, and woke me, and said there were burglars in the house, and that we ought to… er…” He stopped.

“Well?” barked Omri’s father impatiently.

“Well… stop them.”

Omri’s father turned back to Omri. “Stop them? Three grown men? How could you stop them? You should have locked your bedroom door and let them get on with it!”

“They were nicking our TV and stuff!”

“So what? Don’t you know the sort of people they are? They could have hurt you seriously!”

“They did hurt him seriously!” interrupted Omri’s mother in a shrill voice. “Look at him! Never mind the interrogation now, Lionel. I wish you’d go and phone Basia and find out why she didn’t come, and let me take Omri upstairs and look after him.”

So Omri’s father returned to the hall to phone the baby-sitter while his mother led Omri upstairs. But when she switched the bathroom light on and looked at him properly, she let out a gasp.

“But that’s a burn, Omri! How – how did they do that to you?”

And Omri had to say, “They didn’t do it, Mum. Not that. That was something else.”

She stared at him in horror, and then controlled herself and said as calmly as she could, “All right, never mind now. Just sit down on the edge of the bath and let me deal with it.”

And while she was putting on the ointment with her cold, shaky hands, his father came stamping up the stairs to say there was no reply from their baby-sitter’s number.

“How could she not come? How could she leave you boys alone here? Of all the criminally irresponsible – wait till I get hold of her—”

“What about us?” asked Omri’s mother very quietly, winding a bandage round Omri’s head.

“Us?”

“Us. Going out to our party before she got here.”

“Well – well – but we trusted her! Thought she was just a few minutes late—” But his voice petered out, and he stopped stamping about and went into their bedroom to take off his coat.

Omri heard the light being switched on, and bit his lips in suspense.

“Am I hurting, darling?”

He had no time to shake his head before his father burst back.

“What in God’s sweet name has been going on in our bedroom?”

Patrick, who was hanging about in the doorway to the bathroom, exchanged a grim look with Omri.

“Well, Dad – that’s – that’s where the battle – I mean, that’s where they were, when we – caught them.”

“Battle! That’s just what it looks like, a battlefield! Jane, come in here and look—”

Omri’s mother left him sitting on the bath and went through into the bedroom. Omri and Patrick, numb and speechless with suspense, could hear them exchanging gasps and exclamations of amazement and dismay.

Then both his parents reappeared. Their faces had changed.

“Omri. Patrick… I think we’d better hear the whole story before the police arrive. Come in here.”

With extreme reluctance, the boys went through the dividing door between bathroom and bedroom for the second time that evening.

The place looked terrible. All the dressing-table drawers, and those of the chest of drawers, were pulled out, their contents strewn about. The double bed had been knocked askew. A chair had gone flying, the wardrobe door was swinging open. Omri had set his mother’s little jewel-cupboard back on its feet but its door, too, was open.

But, with the lights full on, the thing the boys were most painfully aware of was the holes. Little pin-holes made by the tiny bullets, and not so little ones made by the miniature mortars and hand-grenades which had missed their targets and hit the wall and the head and foot of the bed. It seemed ludicrous to Omri now, looking at them, that he’d had even a faint hope his parents might not notice them. They might be a bit short-sighted, but after all, they weren’t blind. The room looked pock-marked.

And indeed his father was already running his fingers over the white wall above the bed-head.

“What’s been going on here, boys?” he asked in a new tone of voice.

Patrick and Omri glanced at each other, opened their mouths, and closed them again.

“Well?”

It wasn’t a bark this time, it was just a question, a question filled with curiosity. After all, from a grown-up’s point of view, what could make those tiny marks?

At that moment, there was a loud, policemanly ring and double knock on the door.

Omri’s father gave the boys a look which said, “This is only a short postponement”, and left the room. They heard him running downstairs, and they all trailed after him. Halfway down, he paused.

“Good Lord, did you see this, Jane? I didn’t notice as we came up! One of the banisters has been broken!”

Eager to explain something that could be explained, Omri volunteered the information that one of the burglars had fallen downstairs in his hurry to get out.

His father looked up at him.

“You boys must have thrown a real scare into them.”

“Lionel,” said Omri’s mother suddenly.

“What?”

“Shouldn’t we – hear what the boys have to say, before the police talk to them?”

He hesitated. The bell rang again, commandingly.

“Too late now,” he said, and hurried to open the door to the police.

2

Modest Heroes

As the two uniformed policemen were shown into the living-room, and Omri’s mother hurried down to them, Omri and Patrick had a welcome moment to themselves at the top of the stairs.

“You look like a Sikh in that bandage,” said Patrick. “Well, half a Sikh.”

“Never mind what I look like. What are we going to do?”

Patrick said nothing for a moment. Then he said, “Make something up, I suppose. What else can we do?”

“All right. But what? What, that anyone’d believe for two seconds?”

“We might try saying that the skinheads did the damage to the wall. We could say they had – I don’t know – spiked tools, gimlets or chisels or whatever, and just stuck them into everything for a laugh.”

“Or, we could say we don’t know how they did it. We burst in, they ran, that’s it. Leave the cops to figure it out.”

“If they really look, they’ll find minute bullets in the bottoms of the holes.”

“They won’t. Why should they think to?”

“Boys! Come down here, will you?”

It was Omri’s dad calling, peremptorily. They started to walk as slowly as they dared down the stairs.

“And your burn?” whispered Patrick.

“Maybe – we might say we’d had a bonfire in the garden and that you cracked me over the head with a lighted branch.”

“Oh, great! Try saying that and I really will crack you!”

So that was it. They didn’t try to explain the little holes, and the police assumed that the skinheads had been vandals as well as burglars and didn’t examine them too closely. They went over everything else for fingerprints but said that although there were quite a few, the chances were against them catching the thieves who – technically speaking – weren’t thieves after all, because they hadn’t actually got away with anything.

Omri told the bonfire story without bringing Patrick into it. He just said – the inspiration of the moment – that they’d used a whole can of lighter-fluid to get the fire going and that he, Omri, had struck the match while his face was over the wood. His parents, who had been positively bursting with pride at the way the boys had rid the house of intruders, abruptly changed their views about Omri’s brilliance.

“How could you be so unutterably DAFT as to light a fire like that, you little HALF-WIT!” his father expostulated. “How many times have I told you—”

A cough from one of the policemen interrupted him.

“Excuse me, sir. Were these two lads alone in the house?”

“Er—”

“Because as you no doubt know, sir, it is severely frowned on to leave any young person under the age of fourteen alone in a house at night.”

“Of course I know that, Sergeant, and we never, never do it. We always have a baby-sitter. Very punctual and reliable. She was due at seven tonight, and when we went out we assumed she was a couple of minutes late… She’s never let us down before.”

“And where is this person, sir?”

“She never showed up, Sergeant,” said Omri’s father shame-facedly. “Yes, I know what you’re going to say, and you’re perfectly right, we are to blame and I shall never forgive myself.”

“I dare say you will, sir,” said the sergeant levelly, “in time. But it would have been much harder to forgive yourself, if worse had befallen.” Both Omri’s parents hung their heads miserably and Omri moved closer to his mother who looked as if she might burst into tears.

“This is not exactly what you might call a – salubrious neighbourhood, especially after dark,” went on the policeman. “Only this evening, a lady was mugged at the end of your street – pulled right off her bicycle, she was—”

“Her bicycle!”

This from Omri’s mother, whose head had come up sharply.

“Yes, madam…?”

“Who was she – this – lady who was mugged?”

The sergeant glanced at his companion.

“Do you remember the name, George?”

He shrugged. “Some Polish-sounding name…”

Omri’s mother and father exchanged horrified looks. “Not – was it Mrs Brankovsky?”

“Something like that.”

“But that’s her! Our baby-sitter!” cried Omri’s mother. “Oh, heavens – poor Basia—”

“‘Basha’?” inquired the younger policeman. “Is that her name, or what happened to her?” And he suppressed a snigger. But the sergeant gave him a stern look and he subsided.

“There’s nothing humorous about it, George.”

“No, sergeant. Sorry.”

“You’ll be glad to hear she’s not badly hurt, madam. But she had to go to hospital, just for a check-up, like. The muggers got her bag, though.”

“Oh, this is terrible! What kind of district have we come to live in?”

Ah, thought Omri. Now maybe you’ll realize what I’vebeen going through, walking along Hovel Road! They’d never accepted before that it was a horrible area and that he’d been scared.

The policemen took all the details and descriptions of the skinheads.

“Could you identify them if you saw them again?” asked the sergeant.

“No,” said Patrick.

Omri said nothing. He knew he would see them again, like on Monday morning on the way to school. Whether he would decide to shop them, or not, he had yet to decide.

Adiel and Gillon came home from their film just as the police were leaving.

“And who are these young gentlemen?” asked the sergeant.

“They’re Omri’s older brothers.”

“What’s going on?” asked Adiel.

“We’ve had burglars,” said Omri quickly.

“WHA-AT!” yelled Gillon. “They didn’t get my stereo! – Did they?”

“They didn’t get a thing,” said their father proudly. “Omri and Patrick chased them off.”

The older boys gaped at each other.

“Them and what army?” asked Gillon.

Patrick stifled a sudden nervous giggle. “Only a little one,” he murmured. Omri nearly felled him with a heavy nudge.

There was a lot more talking to do – Adiel and Gillon had to hear the whole story (except that of course it was nothing like the whole story) all over again. They were absolutely agog, and even Gillon could find nothing sarcastic to say about the way Omri and Patrick had dealt with the situation.

“You’re a pair of nutters,” was the worst he could think of. “Those thugs could’ve flattened you. How did you know they didn’t have knives?” But there was more than a hint of admiration in his reproof.

Adiel, the eldest, said, “Right couple of heroes if you ask me. We could’ve been cleaned out.” And he gazed lovingly, not at his little brother, but at the television set.

It was nearly one o’clock in the morning by the time they’d drained the last of their hot chocolate and been gently shooed off to bed by Omri’s mother. She gave Omri a special hug, being careful of his head, and hugged Patrick too.

“You’re fantastic kids,” she said.

Omri and Patrick looked uncomfortable. It simply didn’t seem right to either of them that they were getting all the credit for driving off the intruders single- (or double-) handed, when in fact they’d had a great deal of help.

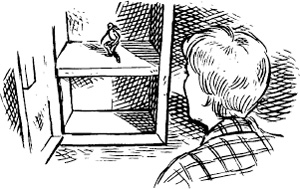

As soon as they got up to Omri’s bedroom in the attic, they locked the door and made for the desk.

They’d had to make a hasty decision, before the return of the parents, to leave things as they were, not to send anybody else back after they’d dispatched Corporal Willy Fickits and his men. As Patrick pointed out, “We don’t know how the wounded would stand the journey. Besides, we can’t send the Indians back to their time without Matron, we can’t send her back to hers, without them – and we certainly can’t send them all anywhere together!”

And Omri agreed. But they’d both been on tenterhooks all the time the police had been in the house for fear they’d demand to see Omri’s room. The boys had been very careful to say the burglars hadn’t got beyond the first floor of the house.

Now the boys bent over the desk. They’d left Omri’s bedside light on in case Matron had had to tend to one of the wounded Indians in the night. She herself now sat, upright but clearly dozing, at a small circular table (made of the screwtop of a Timotei shampoo bottle, a good shape because it had a rim she could get her knees under). On it lay a tiny clipboard that she had brought with her from St Thomas’s Hospital. She’d been making up her notes and temperature charts.

On either side of her on the floor of the longhouse stretched a double row of pallet beds. Each bed was occupied by a wounded Indian. Matron’s ministrations had been so efficient that all were resting peacefully. She had earned her little nap, though she would probably deny hotly, later, that she had nodded off while ‘on duty’.

Outside the longhouse, beside the burnt-out candle, a blanket was spread on the soil in Omri’s father’s seed-tray. Curled up asleep on the blanket were Little Bull and Twin Stars, his wife. Between them, in the crook of Twin Stars’ arm, lay their newborn baby, Tall Bear.

All these people, when they were standing up, were no more than seven centimetres tall.

3

How It All Started

It had all started over a year before, with an old tin medicine-cabinet Gillon had found, a key which fitted it, which had belonged to Omri’s great-grandmother, and the little plastic figure of an American Indian which Patrick had given Omri (second-hand) for his birthday.

On that fateful night, Omri had put the Indian into the small metal cupboard and locked it with the fancy key. There was no particular point to this, really. Thinking back later, Omri didn’t know why he’d done it. He’d had a thing at the time about secret cupboards, drawers, rooms; hiding-places, kept safe from prying eyes, where he could secrete his favourite things and be sure they’d stay exactly as he’d left them, undisturbed by rummaging brothers or anyone else.

But the Indian didn’t stay as he’d left it. Some combination of key and cupboard, plus the stuff the Indian was made of – plastic – had worked the wonder of bringing the little man to life.

At first, when this happened, Omri – once past the first shock of astonishment – had thought he was in for the fun-trip of all time. A little, live man of his very own to play with! But it hadn’t turned out like that.

The Indian, Little Bull, was no mere toy. Omri soon found out that he was a real person, somehow magicked into present-day London, England, from the America of nearly two hundred years ago. The son of a chief of the Iroquois tribe, a fighter, a hunter, with his own history and his own culture. His own beliefs and morals. His own brand of courage.

Little Bull regarded Omri as a magic being, a giant from the world of spirits, and was, at first, terrified of him. Omri could see he was afraid, but the Indian was incredibly brave and controlled and Omri soon began to admire him. He realized he couldn’t treat him just as a toy – he was a person to be respected, despite his tiny size and relative helplessness.

And it soon turned out that he was by no means the easiest person in the world to get along with, or satisfy. He had demands, and he made them freely, assuming Omri to be all-powerful.

He demanded his own kind of food. A longhouse, such as the Iroquois used to sleep in. A horse, although previously he had never ridden. Weapons, and animals to hunt, and a fire to cook on and dance around. Eventually he even demanded that Omri provide him with a wife!

In addition, Omri had to hide him and protect him. It needed only a little imagination to realize what would happen if any grown-up should find out about the cupboard, the key and their magic properties. Because Omri soon found out that not just Little Bull but any plastic figure or object would become alive or real by being locked in the cupboard.

But he couldn’t keep the secret entirely to himself. His best friend, Patrick, eventually found out about it, and lost no time in putting his own little plastic man into the cupboard. And so ‘Boo-Hoo’ Boone, the crying Texas cowboy, had come into their lives, complicating things still more. For of course, cowboy and Indian were enemies, and had to be kept apart until a number of adventures, and their common plight – being tiny in a giants’ world – brought them together and made them friends and even blood-brothers.