Полная версия

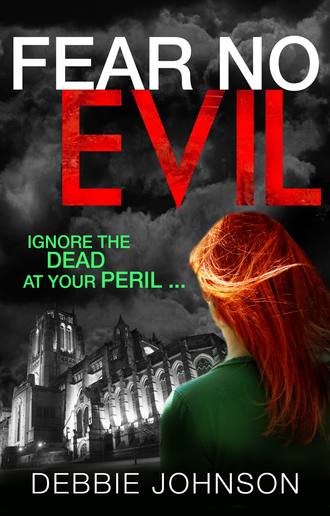

Fear No Evil

‘What do you mean?’

‘I don’t know what it fucking means, do I? By that stage I had blood coming out of me ears and nose, and frigging Wigwam dragged me out of there by me boots, banged me arse all the way down the pissing stairs! Next thing I knew we were out on the street. He had me lying down on the seat at one of them yellow bus stops, shaking me, like that was going to help. He was furious – with hisself I think, ’cause he was scared as well. He chucked me in the backseat of that wagon he drives round in and took me back where I was living then.’

He sucked in breath, and I could hear it rattle round his blackened lungs. I’m not psychic – but I had the horrible feeling Dodgy Bobby wasn’t long for this world. Even as the thought crossed my mind, he looked up sharply.

‘You might be right, love. And I’m terrified of what comes next. I’ve been hiding out ever since, and I’ve been going to St Anthony’s every day and confessing. But none of it works – I can still feel it. Like smoke that’s got on my clothes and won’t wash out. It did something to me. It… claimed me. Like no bugger else has ever wanted to do.’

He was staring at the fish tank again now. His hands had stopped jolting, and some colour was creeping back into his cheeks. I exhaled, without realising I’d been holding my breath. Fuck. What a horrible story. From a horrible man. In a horrible place. I needed a beer, and possibly a Valium.

‘Bobby,’ I said, ‘last question then I’ll leave you in peace. Where did Geneva live? Where did all this happen?’

‘You’ll know the place, love,’ he said, ‘big old building on the edge of town. Don’t ever go there if you can avoid it. Hart House.’

Chapter 9

‘What do you mean I need to speak to the press office?’ I squeaked, annoyed that my lies weren’t working.

It was just after 11 o’clock the next day, and I was on the phone to the Head of Archives at the Liverpool Institute.

I’d made up a great story about working for the Gazette, and wanting to write a feature about the history of the Institute’s buildings, focusing on Hart House. My Land Registry search had come back listing a corporation called Stag Industries, which I’d never heard of. It was probably a commercial subsidiary of the Institute, but I was going to have to talk to somebody at Companies House later in the day to find out more.

In the meantime, I used the local journalist ploy. It worked much better a few years ago, I can tell you. People were impressed and interested and wanted to get their names in the papers. These days they either wanted paying, signed up to Max Clifford, or referred you to some corporate relations guru with a 2:2 in Media Studies and perfectly manicured nails. The state of the bloody nation.

There was a knock at the door, and I glanced up as it opened. Dan walked in. Father Dan, I mean. I had to really work on that Father Dan business, especially when he looked like he did today – sex on a stick, as my mate Tish might say.

He nodded hello, and lingered in the doorway, filling up the frame with Levi-clad legs, broad shoulders and a leather jacket, his dark blonde hair kissing the collar. I smiled and pointed at the phone in a ‘one minute’ gesture, while the Head of Archives continued to waste my time.

‘Well I don’t see what use the press office would be. I bet they don’t know about the history of Hart House, do they, not like you do with your experience? I’m sure they’d want you to talk to me – a feature in the Gazette would be a real boost for them and their fundraising drives… what? Are you sure? Oh. Okay, I’ll hold.’

I didn’t. I slammed the phone down, hard enough to make my pencil holder shake. I had no desire to talk to the press office. They’d probably want to call me back at the Gazette. I could arrange for Tish to help me, she’s a writer there, but it’d take time to set up and I was hoping to not be arsed with it all. I was slightly aggrieved, and frowning deeply.

‘Isn’t there some kind of law against that?’ said Father Dan, easing himself down into one of the creaky leather chairs, stretching his legs out in front of him and crossing his ankles. He was wearing very nice brown suede boots, I noticed. Still with odd socks, though.

‘Against what?’

‘Impersonating a member of the free press?’

‘No, there’s not, and I’d know if there was, wouldn’t I? When did you get here anyway? Where are you parked? Does that T-shirt have a hole in it?’

I was fudging it. There may well have been a law against what I’d been doing. Now was not the time to ponder.

He looked down at his own chest – and who could blame him? – spotting the ragged tear that hovered over his stomach. He pulled at it a bit, then shrugged.

‘Looks like it does. Sorry – didn’t realise there was a dress code. Nice office, by the way. Pretty old, isn’t it? What was this building used for originally?’

He gazed around, taking in the high ceilings, original coving, and the enormous picture window. Parquet flooring, dating back to the days when it was fashionable first time round; filing cabinets tucked away in an alcove that looked like it could originally have been home to a Roman bust or a priceless oil painting. Everything coated liberally with cobwebs to give it exactly the shabby chic air I was going for. Honest.

‘Oh, don’t start with that crap, we’ve got work to do,’ I said, bustling things around on my desk. I really didn’t want to have that conversation. When I arrived at the office that morning, I felt nervous, which in turn made me a bit pissed off.

I’d opened the door, found my desk drawer sticking out, as usual. The pencils were out of the pot and scattered on the surface. The files all looked in place, but when I went in to the loo, the toilet brush was submerged in the toilet.

‘Okay, you fucker,’ I’d said, to the four walls and empty air and potential ghost, ‘stop messing me around. I am going to put my keys here, safely, next to the phone. And they are going to stay there Or Else – do you understand me?’

I’d used my very best kick-ass voice, but couldn’t help feeling stupid. I wasn’t just talking to myself, I was shouting at myself. Things could go rapidly downhill from here. I’d be one of those people you avoid sitting next to on the bus, carrying a plastic bag full of documents and wearing my dinner.

‘All right, Little Miss Bossy,’ said Dan, apparently and annoyingly finding me amusing, ‘let’s do some work. Have you got the diary?’

I pointed at a brown-paper wrapped package perched on the corner of the desk. It had come special delivery earlier that morning, but I’d been too busy to open it. Actually, that wasn’t strictly true. I felt a reluctance to open it, if I was honest. Something was throwing me slightly off balance – Dodgy Bobby’s tale of terror; Father Dan’s assertion that the world wasn’t quite what I thought it was; the fact that my bloody office appeared to be haunted. Every time I’d reached out to tear off the packaging, my fingers had snatched themselves away and got busy with something else. Like my hands and the diary were two magnets, repelling each other.

I felt embarrassed and ashamed about my reaction. That diary was a crucial piece of evidence in a case I was working on. I should be desperate to read it, not finding excuses to avoid it. I also had the full police file on Joy, snaffled from Corky Corcoran, to get through – but somehow that, with its safe science and familiar terminology and photos of a battered and bleeding teenaged body, felt less daunting.

Dan was staring at me, his ice blue eyes slightly narrowed.

‘Do you want me to open it?’ he asked. I nodded in return, and he picked the package up.

‘Don’t worry. You’re a lot more sensitive to this stuff than you want to admit. Do you feel edgy, like you don’t want to touch it?’

‘Don’t be stupid!’ I snapped, getting up to do some dusting. It urgently needed doing – that bookshelf was an absolute disgrace. I used my shirt sleeve to wipe the top of it over, buying myself a minute to Get A Fucking Grip. I took a deep breath, and went back to sit down. I pulled out the police file, reassuring in all its manila-foldered glory, and started from scratch. I was aware of Dan unwrapping the diary, and frowning as he flicked through the pages.

We both worked silently, with me occasionally sneaking a peek at him as he read. His face didn’t give much away, but for all I knew, he wasn’t at the juicy bits yet. Maybe he was reading about Joy’s nights at the local wine bar or her trips to the cinema with cute boys from the medical school.

I, on the other hand, was reading about how she was seen cartwheeling from her window at 8.02 a.m. on June 13th. The poor traumatised witnesses – cleaners walking home from mopping floors in a city office block – saw her land on the concrete path that led up to Hart House. I turned forward to the photos, and the gory details that Mr and Mrs Middlemas wouldn’t have had access to.

Joy was lying crumpled on the ground, one leg bent beneath her like a brutalised mannequin. Her head was surrounded by pooling red blood, her long brown hair trailing cobwebs through it. Not the best way to see someone for the first time, but you could tell she’d been a pretty girl. A touch of make-up. One high-heeled shoe on, the other flung a few feet away.

Bleeding in the brain; fractures to the pelvis, arms, legs; crush injuries to the chest, a break in the spinal cord. I’ve seen fall victims survive bigger plunges than hers, but even if she had made it, she’d have been left paralysed and brain damaged.

Forensics checked her room. Nothing out of place. The textbooks on the bay seat suggested she’d been revising for her second year exams. I made a note of the titles – ‘Dissection of the Dog’, ‘Clinical Anatomy of the Cat’, ‘Biochemistry of Domestic Animals’… perfect light reading. If I was ever suffering from insomnia, I knew which part of the library to head for.

Joy’s window was open, banging to and fro in the breeze. No sign of a break, a push, a shove. It was unlocked, untampered with, no fingerprints other than Joy’s, and others who’d been accounted for, like cleaners and maintenance men and some of her friends. No indication at all that she intended to do herself in. Everyone seemed to have done a thorough job, from the first bobby on the scene through to the D.I who followed it through.

D.I Alec Jones. I knew the name, but the computer in my brain hadn’t filed a photo next to it. Probably meant he arrived after I’d resigned, but I’d heard the others mention him. Maybe met him at a retirement do or something. I made a note of his number so I could pursue him later. I flicked on through the file. I noticed a new surge of activity towards the end, extra pages tagged in after the inquest date. No mention of a ghostly bad guy, but it timed perfectly with Mrs M reading Joy’s diary and getting a giant bee in her bonnet about it.

From what I could see, the D.I had done his best. Re-interviewed, re-visited, re-thought. Still nothing to dissuade him from the theory that Joy had leaned back on the window, forgetting she’d left it open, and fallen to her death. Rose Middlemas was bitter and angry about the way the police had performed – but Alec Jones had gone above and beyond on this one, when he was probably struggling with a leaning tower of Pisa of other cases at the same time.

A few things were bugging me, though, and I jotted them down to talk to D.I Jones about as soon as I tracked him down. I was betting he’d be less than thrilled to have this one come back to haunt him. No pun intended.

‘How’s it going, Father Dan?’ I asked, looking up at the glowing hunk of sex appeal sitting opposite me.

‘Stop calling me Father Dan,’ he said, without even raising his eyes. It seemed to annoy him, which I found very enjoyable. Naughty me. He finished reading the page he was on, then closed the book and placed it back on top of the desk. It was a hardback journal, covered in a delicate purple floral design. A pretty book for a pretty girl who came to an ugly end.

He looked agitated, and ran his hand through his hair, leaving it displaced in thick blonde furrows.

‘Let’s go to Hart House,’ he said.

Chapter 10

Half an hour later we were standing outside. It was another warm day, but we were in the shadow of Hart House, where the air was cool and breezy.

It was even uglier in real life – all neo-Gothic red brick arches and gargoyles with ironically raised eyebrows. The top floor was edged by fake castellations, with a turret at each corner. There might have been a roof garden up there at one time, or an observation point for looking out over the Mersey.

Students bustled in and out of the front doors, books tucked under their arms, backpacks hanging from their shoulders, all looking unfashionably earnest. This must be the Hall for Hard Workers, which might explain why I never lived here. I was firmly in the Hall for Slackers, where the heaviest thing we carried round was a four-pack of Stella and a bad attitude.

There was a bike park to the left of the main entrance, and I noticed the residents using plastic swipe cards to get in and out of the building. The patch of grass outside was bald and faded, like a threadbare carpet, its only decoration a litter bin. The concrete path leading up to the grandiose double doors was clean apart from a few globs of chewing gum, and completely unmarked by the fact that only a few months ago, Joy Middlemas was lying there with her brains splattered all over the paving, bleeding out her last moments on earth.

Dan had been quiet and moody on the drive over. The few times I asked him a question, he snapped back at me, so I gave up. I suppose reading the diary of a dead girl could make the jolliest of souls testy. I couldn’t complain – so far I’d wussed out of reading it at all.

I snuck a look at him. The ‘something’ he’d needed to grab from his van turned out to be a black shirt and trousers and a dog collar, all of which he was now wearing.

‘Isn’t there some kind of law against that?’ I’d asked sarcastically when he emerged from the loo, transformed. ‘Impersonating a member of the priesthood?’

‘Possibly, but I assume you’d know,’ he said. ‘Personally I don’t care, and I don’t think God does – it helps me get in to places. Nobody likes to be rude to a priest.’

I was about to prove him wrong on that point, but he’d pre-empted me by walking out of the door without another word. I consoled myself by being rude to a priest’s back, with two of my fingers.

The security at Hart House wasn’t too bad at all. As well as the swipe card system, I could see CCTV cameras at strategic points, and there was a uniformed guard visible behind a small desk in the lobby. The car park off to the rear had another swipe card entry system, with a barrier that swung up and down on demand. Nothing that would stop anyone serious about their trade, but enough to deter a passing thief or pervert.

‘Come on,’ said Dan, striding ahead. I wasn’t sure if I was glad about the dog collar thing or not. On the one hand, it made it easier to think of him as Father Dan. On the other, it made me feel even more guilty that I was admiring the length of his legs as he disappeared off towards the door. It was a moral dilemma. Or potentially an immoral one.

A girl came out of the door, about nineteen, pretty as a picture with flowing blonde hair and huge blue eyes. She was wearing bell bottom jeans and a fur-fringed suede jacket. Back to the seventies. She looked up as Dan approached, did a slight double take, then smiled at him. Dazzled by his priestly splendour, or maybe that one dimple of his, she held the door open for him. So much for the swipe cards. Security is only as secure as the idiot using it.

‘Thank you,’ I mumbled as she passed, although she clearly hadn’t even noticed I existed. I wasn’t sure I liked the way I was becoming invisible in the presence of the man in black.

The guard glanced at us as we entered, and I saw his eyes clock the dog collar immediately. He was middle-aged and looked like his two favourite hobbies were drinking beer and watching telly.

‘Good afternoon,’ said Dan, confidently, walking past as though he had every right to be there.

The guard nodded and smiled. ‘Afternoon, Father,’ he said, going back to his copy of the Daily Star.

‘Told you it worked,’ he said as we headed to the stairs. Smug bastard. I was sure I’d have got in somehow, probably by telling some kind of big fat fib and carrying a clipboard. For some reason people always take you seriously if you have a clipboard.

Inside, it was cool and calm and dark. The floor of the lobby was parquet, stubbed by a million toes; the staircase probably killed off an entire forest of oak at some point. Now the steps were hidden by shabby brown carpet, and the banisters were untouched by the hand of Mr Pledge. The stairs were quiet – the students, being by definition brainy types, were all using the lift instead of trekking up and down by foot.

Joy had lived on the fifth floor, from the address her parents had given me, and I knew that’s where Father Dan would be heading. I’m pretty fit, but he’s a lot taller, and was taking the steps two at a time. I lost sight of him as he turned the bend up onto the fifth, then put a spring on to catch him up. He’d stopped dead on the top step, which opened up onto the same small landing we’d seen on numbers one, two, three and four.

I stood just behind him, getting an eyeful of a perfectly formed arse hovering two stairs above me.

‘Can you feel it?’ he asked.

I stayed quiet. I wasn’t quite sure what he was talking about, but I was fairly certain it wasn’t his arse.

It did feel a little colder here. No breeze, but a slight drop in temperature that, now I came to think about it, was giving me goosebumps. Dan had gone silent again, and there was no noise from outside filtering through the sound-proofed windows. Deadly quiet. I started to feel the fine hairs on the back of my neck tingle, and pushed past Dan to distract myself.

Four doors, all painted a vomitous shade of beige, each with a number painted on them in that military-style font that reminds you of army surplus or prisons.

I stopped next to him, feeling my heart beating faster than usual in my chest. Dan was still quiet, staring at the door to Joy’s room as though he was magicking up X-ray vision to look through solid wood. I planned something a bit more straightforward, and marched over to knock on it just in case someone else had moved in.

No reply. I banged again, for good measure, and to create some noise. All this quiet was spooking me, as was Dan’s expression. He was frowning, concentrating really hard like he was trying to remember his nineteen times table while balancing a sherry trifle on his head.

‘In her diary, she talks about this hallway,’ he said. ‘About coming up those stairs, or out of the lift, and feeling the cold hit her. She noticed it when she first moved in and reported it to the maintenance staff. They checked the heating and nothing was wrong. They all felt it was cold as well, but when they gauged the temperature, it showed the same as the rest of the building. To start off with she just mentions it, in passing. Later, she says it “got into” her room. Those are the words she used – “it got into my room”. That was a couple of months before she died, and after that she was always cold in there. Always.’

I couldn’t stop myself from shivering. I reached out and tried the door handle. Locked.

‘Can you get us in there?’ he asked abruptly, face set like stone.

I considered protesting, and explaining that would be an invasion of someone’s civil liberties, but one look at him changed my mind. He wasn’t scared, like I was. He was furious. Something here was making Dan mightily angry, and I had the feeling he’d shoulder-charge the door until he knocked it off its hinges if I didn’t intervene.

I’m halfway ashamed to admit this, but I carry lock picks round with me. They’re rarely used for anything other than breaking into my own flat when I’ve lost the keys, but it’s a good set, made for me by a professional locksmith called Lenny the Slipper. Slipper because he was always slipping into places he shouldn’t be. Lenny could never resist the temptation of other people’s houses. He never took anything – just looked around, rifled through the odd knicker drawer, played a few mind games, like eating leftovers from the fridge. He came a cropper when he was caught nosing round the squillion-pound home of a Liverpool Football Club striker. The window cleaner saw him taking a dip in the pool and called us out. He ended up doing community service – litter picking round Anfield, funnily enough. When I resigned and set up shop on my own, I paid him fifty quid and got my picks and a masterclass in return.

I pulled the small wallet from my back pocket and got the two tools I needed. I kneeled down, fiddled until I got a feel for it, then slid the slim edge of the pick in, popping up the pins until the cylinder turned. It took about forty seconds. I gave a little snort of pleasure – one of my quickest yet. It’s the small triumphs that keep you going in life. I avoided Dan’s eyes. It was probably wrong to be so proud of something so bad.

I stood up and gently pushed the door, checking for a chain.

‘Hello! Repairs!’ I shouted as I walked in. Just in case there was a comatose student in there after all, stoned to oblivion or passed out with his head in a copy of A Vet’s Guide to Dog Poo.

I needn’t have bothered. Nobody lived here. Bed stripped bare, open wardrobes empty apart from dangling wire coat hangers; bookshelves clear of anything other than dust. It was also so cold I was chilled to the bone, and wrapped my arms round myself to try and keep warm.

Dan followed me in, opening up Joy’s diary and reading out loud. Which was just what I needed.

‘June 2 – stayed in the library until it closed at 11 tonight. Couldn’t bear the thought of coming back here. It’s so cold. And there’s something here. I know there is. I look in the mirror and I feel something watching me. I take showers in the sports block now; I can’t stand being naked in here. I’m scared of going to sleep. I hear the laughing, all the time. At first I thought it was from another room, coming up through the heating pipes or something. But it’s not. It’s in here. It’s laughing at me, and the more I look round, the more it laughs. It. They. Sometimes it sounds like a man, sometimes like a bunch of school kids. I’m considering getting a boyfriend, or sleeping with that awful bloke from downstairs, just so I don’t have to stay here. Sophie says I’m just stressed and I work too hard. I’m not stressed. I’m scared.’

I walked over to the mirror, stared at my own reflection. Felt nothing but the cold, and the received fear that oozed off Joy’s words. There was still a toothbrush in a holder on the shelf. Probably hers. I touched it with one finger and it clinked against the glass.

Dan sat down on the bed, and carried on reading: ‘June 11th. I don’t know if I can carry on. Everyone thinks I’m nuts. She doesn’t think I know, but Sophie’s told Dr Wilbraham I’m losing it. They want me to see some kind of guidance counsellor. And this thing, here. It wants me to die. I know it does. I hear them at night, whispering at me. Things have started to move now – the books fly off the shelves, and my covers get pulled off me, and they sing. Bloody nursery rhymes. I’ve asked for a transfer again, but I keep getting told there’s nowhere until next term. I think I might ask Mum and Dad for the money to rent my own place. I’d rather live in a cardboard box than here. Sometimes I sleep over on Sophie’s floor. I pretend I’m drunk and passed out. But now she’s seeing Lawrence, so I can’t do that as much. I need to get out.’

I wanted to tell him to shut up. I wanted to leave this room. I wanted to dump this case and wrap myself up in a duvet with a bottle of Bushmills for company.