полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 493, June 11, 1831

"Glorious! Capital! Ten thousand thanks for that superb aphorism. Doctor, you must recollect that for me to-morrow morning, and you must put it down for me in your best style." He then went on hiccuping and muttering—"The best use, hic, the best use, hic, I can make of my, hic, the tongue, hic, hold your tongue, hic, oh doctor hic, I shall never forget, hic, I hope you will remind me of it, hic, to-morrow morning."

The old gentleman shook his head and sighed; the tipsy orator proceeded, and directing his speech to Atherton he managed to say, with many interruptions, "Young gentleman, you may think yourself happy in having thus accidentally as it were, for it was all by pure accident, been introduced to the great Dr. Johnson. And if you need any advice or direction, you are now at the fountain head of all practical wisdom. My friend's comprehensive genius takes in all subjects from the government of empires to the construction of an apple dumpling. Follow his advice and you cannot do wrong, neglect it and you cannot do right.—Is not that well said, Doctor?—Rather tersely put?"

"Go to sleep, Bozzy," said the doctor, "you don't know what you are talking about, go to sleep."

"But I know what you have been talking about. My ears are always awake to your wisdom, when all my other senses are asleep. We have had a glorious day of it, Doctor, you routed them all, they had not a word to say for themselves."

"I wish it were so with you," replied the Doctor.

"Good again! Put that down;" said Mr. Boswell, and then turning to Atherton, he continued, "You see how free I am with my illustrious friend."

"Be quiet, Bozzy," said the doctor again.

"Well, well I may go to sleep contentedly to-night, for I have not lost a day. I shall record it all to-morrow, and that fine glorious laugh which you uttered as we came through Temple Bar; I shall never forget the awful reverberation. There is not a man in Europe whose laugh can be compared with yours.—I shall never forget it;—pray remind me of it to-morrow morning,—I shall never, never forget it, never nev—nev." So saying he fell fast asleep.

We like this portrait-painting turn of the author. Its identity is very entertaining, and is very superior in interest to the satirical nommes in the fashionable novels of our day.

SPIRIT OF THEPublic Journals

LINES ON THE VIEW FROM ST. LEONARD'S

BY THOMAS CAMPBELLHail to thy face and odours, glorious Sea!'Twere thanklessness in me to bless thee not,Great beauteous Being! in whose breath and smileMy heart beats calmer, and my very mindInhales salubrious thoughts. How welcomerThy murmurs than the murmurs of the world!Though like the world thou fluctuatest, thy dinTo me is peace—thy restlessness repose.E'en gladly I exchange your spring-green lanesWith all the darling field-flowers in their prime,And gardens haunted by the nightingale'sLong trills and gushing ecstacies of songFor these wild headlands and the sea mew's clang—With thee beneath my window, pleasant Sea,I long not to o'erlook Earth's fairest gladesAnd green savannahs—Earth has not a plainSo boundless or so beautiful as thine;The eagle's vision cannot take it in.The lightning's wing, too weak to sweep its space,Sinks half way o'er it like a wearied bird;—It is the mirror of the stars, where allTheir host within the concave firmament,Gay marching to the music of the spheres,Can see themselves at once—Nor on the stageOf rural landscape are their lights and shadesOf more harmonious dance and play than thine.How vividly this moment brightens forth,Between grey parallel and leaden breadths,A belt of hues that stripes thee many a league,Flush'd like the rainbow or the ringdove's neck,And giving to the glancing sea-bird's wingThe semblance of a meteor.Mighty Sea!Cameleon-like thou changest, but there's loveIn all thy change, and constant sympathyWith yonder Sky—thy mistress; from her browThou tak'st thy moods and wear'st her colours onThy faithful bosom; morning's milky white,Noon's sapphire, or the saffron glow of eve;And all thy balmier hours' fair Element,Have such divine complexion—crisped smiles,Luxuriant heavings, and sweet whisperings,That little is the wonder Love's own QueenFrom thee of old was fabled to have sprung—Creation's common! which no human powerCan parcel or inclose; the lordliest floodsAnd cataracts that the tiny hands of manCan tame, conduct, or bound, are drops of dewTo thee that could'st subdue the Earth itself,And brook'st commandment from the Heavens aloneFor marshalling thy waves—Yet, potent Sea!How placidly thy moist lips speak e'en nowAlong yon sparkling shingles. Who can beSo fanciless as to feel no gratitudeThat power and grandeur can be so serene,Soothing the home-bound navy's peaceful way.And rocking e'en the fisher's little barkAs gently as a mother rocks her child?—The inhabitants of other worlds beholdOur orb more lucid for thy spacious shareOn earth's rotundity; and is he notA blind worm in the dust, great Deep, the manWho sees not, or who seeing has no joy,In thy magnificence? What though thou artUnconscious and material, thou canst reachThe inmost immaterial mind's recess,And with thy tints and motion stir its chordsTo music, like the light on Memnon's lyre!The Spirit of the Universe in theeIs visible; thou hast in thee the life—The eternal, graceful, and majestic life—Of nature, and the natural human heartIs therefore bound to thee with holy love.Earth has her gorgeous towns; the earth-circling seaHas spires and mansions more amusive still—Men's volant homes that measure liquid spaceOn wheel or wing. The chariot of the land,With pain'd and panting steeds, and clouds of dust,Has no sight-gladdening motion like these fairCareerers with the foam beneath their bows,Whose streaming ensigns charm the waves by day,Whose carols and whose watch-bells cheer the night,Moor'd as they cast the shadows of their mastsIn long array, or hither flit and yondMysteriously with slow and crossing lights,Like spirits on the darkness of the deep.There is a magnet-like attraction inThese waters to the imaginative power,That links the viewless with the visible,And pictures things unseen. To realms beyondYon highway of the world my fancy flies,When by her tall and triple mast we knowSome noble voyager that has to wooThe trade-winds, and to stem the ecliptic surge.The coral groves—the shores of conch and pearl,Where she will cast her anchor, and reflectHer cabin-window lights on warmer waves,And under planets brighter than our own:The nights of palmy isles, that she will seeLit boundless by the fire fly—all the smellsOf tropic fruits that will regale her—allThe pomp of nature, and the inspiritingVarieties of life she has to greet,Come swarming o'er the meditative mind.True, to the dream of Fancy, Ocean hasHis darker hints; but where's the elementThat chequers not its usefulness to manWith casual terror? Scathes not earth sometimesHer children with Tartarean fires, or shakesTheir shrieking cities, and, with one last clangOr hells for their own ruin, strews them flatAs riddled ashes—silent as the grave.Walks not Contagion on the Air itself?I should—old Ocean's Saturnalian daysAnd roaring nights of revelry and sportWith wreck and human woe—be loth to sing;For they are few, and all their ills weigh lightAgainst his sacred usefulness, that bidsOur pensile globe revolve in purer air.Here Morn and Eve with blushing thanks receiveTheir fresh'ning dews, gay fluttering breezes coolTheir wings to fan the brow of fever'd climes,And here the Spring dips down her emerald urnFor showers to glad the earth.Old Ocean wasInfinity of ages ere we breathedExistence—and he will be beautifulWhen all the living world that sees him nowShall roll unconscious dust around the sun.Quelling from age to age the vital throbIn human hearts, Death shall not subjugateThe pulse that swells in his stupendous breast,Or interdict his minstrelsy to soundIn thund'ring concert with the quiring winds;But long as Man to parent Nature ownsInstinctive homage, and in times beyondThe power of thought to reach, bard after bardShall sing thy glory, BEATIFIC SEA! Metropolitan.3THE LATE MR. ABERNETHY

Mr. Abernethy, although amiable and good-natured, with strong feelings, possessed an irritable temper, which made him very petulant and impatient at times with his patients and medical men who applied to him for his opinion and advice on cases. When one of the latter asked him once, whether he did not think that some plan which he suggested would answer, the only reply he could obtain was, "Ay, ay, put a little salt on a bird's tail, and you'll be sure to catch him." When consulted on a case by the ordinary medical attendant, he would frequently pace the room to and fro with his hands in his breeches' pockets, and whistle all the time, and not say a word, but to tell the practitioner to go home and read his book. "Read my book" was a very frequent reply to his patients also; and he could seldom be prevailed upon to prescribe or give an opinion, if the case was one which appeared to depend upon improper dieting. A country farmer, of immense weight, came from a distance to consult him, and having given an account of his daily meals, which showed no small degree of addiction to animal food, Mr. Abernethy said, "Go away, sir, I won't attempt to prescribe for such a hog."

He was particular in not being disturbed during meals; and a gentleman having called after dinner, he went into the passage, put his hand upon the gentleman's shoulders, and turned him out of doors. He would never permit his patients to talk to him much, and often not at all: and he desired them to hold their tongues and listen to him, while he gave a sort of clinical lecture upon the subject of the consultation. A loquacious lady having called to consult him, he could not succeed in silencing her without resorting to the following expedient:—"Put out your tongue, madam." The lady complied. "Now keep it there till I have done talking." Another lady brought her daughter to him one day, but he refused to hear her or to prescribe, advising her to make the girl take exercise. When the guinea was put into his hand, he recalled the mother, and said, "Here, take the shilling back, and buy a skipping-rope for your daughter as you go along."—He kept his pills in a bag, and used to dole them out to his patients; and on doing so to a lady who stepped out of a coronetted carriage to consult him, she declared they made her sick, and she could never take a pill. "Not take a pill! what a fool you must be," was the courteous and conciliatory reply to the countess. When the late Duke of York consulted him, he stood whistling with his hands in his pockets; and the duke said, "I suppose you know who I am." The uncourtly reply was, "Suppose I do, what of that?" His pithy advice was, "Cut off the supplies, as the Duke of Wellington did in his campaigns, and the enemy will leave the citadel." When he was consulted for lameness following disease or accidents, he seldom either listened to the patient or made any inquiries, but would walk about the room, imitating the gait peculiar to different injuries, for the general instruction of the patient. A gentleman consulted him for an ulcerated throat, and, on asking him to look into it, he swore at him, and demanded how he dared to suppose that he would allow him to blow his stinking foul breath in his face! A gentleman who could not succeed in making Mr. Abernethy listen to a narration of his case, and having had a violent altercation with him on the subject, called next day, and as soon as he was admitted, he locked the door, and put the key into his pocket, and took out a loaded pistol. The professor, alarmed, asked if he meant to rob or murder him. The patient, however, said he merely wished him to listen to his case, which he had better submit to, or he would keep him a prisoner till he chose to relent. The patient and the surgeon afterwards became most friendly towards each other, although a great many oaths passed before peace was established between them.

This eccentricity of manner lasted through life, and lost Mr. Abernethy several thousands a year perhaps. But those who knew him were fully aware that it was characteristic of a little impatient feeling, which only required management; and the apothecaries who took patients to consult him, were in the habit of cautioning them against telling long stories of their complaints. An old lady, who was naturally inclined to be prosy, once sent for him, and began by saying that her complaints commenced when she was three years old, and wished him to listen to the detail of them from that early period. The professor, however, rose abruptly and left the house, telling the old lady to read his book, page so and so, and there she would find directions for old ladies to manage their health.

It must be confessed, Mr. Abernethy, although a gentleman in appearance, manner, and education, sometimes wanted that courtesy and worldly deportment which is considered so essential to the medical practitioner. He possessed none of the "suaviter in modo," but much of the eccentricity of a man of genius, which he undoubtedly was. His writings must always be read by the profession to which he belonged with advantage; although, in his great work upon his hobby, his theory is perhaps pushed to a greater extent than is admissible in practice.—His rules for dieting and general living should be read universally; for they are assuredly calculated to prolong life and secure health, although few perhaps would be disposed to comply with them rigidly. When some one observed to Mr. Abernethy himself, that he appeared to live much like other people, and by no means to be bound by his own rules, the professor replied, that he wished to act according to his own precepts, but he had "such a devil of an appetite," that he could not do so.

Mr. Abernethy had a great aversion to any hint being thrown out that he cured a patient of complaint. Whenever an observation to this effect was made, he would say, "I never cured any body." The meaning of this is perfectly obvious. His system was extremely wise and rational, although, as he expressed himself to ignorant persons, it was not calculated to excite confidence. He despised all the humbug of the profession, and its arts to deceive and mislead patients and their friends, and always told the plain truth without reserve. He knew that the term cure is inapplicable, and only fit to be used by quacks, who gain their livelihood by what they call cures, which they promise the patient to effect. Mr. Abernethy felt that nature was only to be seconded in her efforts, by an art which is derived from scientific principles and knowledge, and that it is not the physician or surgeon who cures, but nature, whom the practitioner assists by art. Weak-minded persons are apt to run after cures, and thus nostrums and quacks are in vogue, as if the living human system was as immutable in its properties as a piece of machinery, and could be remedied when it went wrong as the watchmaker repairs the watch with certainty, or the coachmaker mends the coach. No one appreciated more highly the value of medicine as a science than Mr. Abernethy; but he knew that it depended upon observation and a deep knowledge of the laws and phenomena of vital action, and that it was not a mere affair of guess and hazard in its application, nor of a certain tendency as to its effects.

This disposition of mind led the philosopher to disregard prescribing for his patients frequently, as he had less faith in the prescription than in the general system to be adopted by the patient in his habits and diet. He has been known accordingly, when asked if he did not intend to prescribe, to disappoint the patient by saying, "Oh, if you wish it, I'll prescribe for you, certainly." Instead of asking a number of questions, us to symptoms, &c., he usually contented himself with a general dissertation, or lecture and advice as to the management of the constitution, to which local treatment was always a secondary consideration with him altogether.

When patients related long accounts of their sufferings, and expected the healing remedy perhaps, without contemplating any personal sacrifices of their indulgences, or alteration of favourite habits, he often cut short their narratives by putting his fore-finger on the pit of their stomachs, and observing, "It's all there, sir;" and the never-failing pill and draught, with rigid restrictions as to diet, and injunctions as to exercise, invariably followed, although perhaps rarely attended to; for persons in general would rather submit to even nauseous medicine than abandon sensual gratifications, or diminish their worldly pleasures and pursuits.—Metropolitan.

The Gatherer

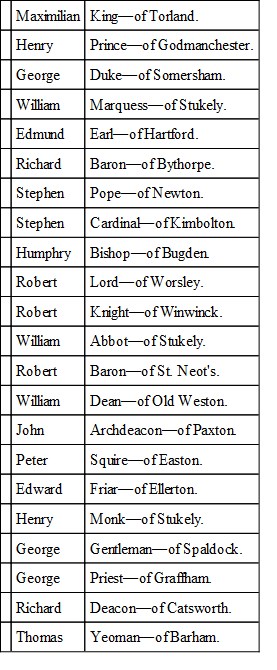

REMARKABLE JURY AT HUNTINGDON

In the 16th century, when figure and fortune, or quality and wealth, were more considered than wisdom or probity, or justice and equity, in our courts of law, Judge Doddridge took upon him to reprimand the sheriff of the county of Huntingdon, for impanneling a grand jury of freeholders who were not, in his opinion, men of figure and fortune. The sheriff, who was a man of sense, and of wit and humour, resolved at the next assizes to try how far sounds would work upon that judge, and gain his approbation. He presented him with the following pannel, which had the desired effect, for when the names were read over emphatically, the judge thought that he had now indeed a jury of figure and fortune:—

A true copy of a Jury taken before Judge Doddridge, at the Assizes holden at Huntingdon, July, 1619.

THE NEW PARLIAMENT "DISHED."

(For the Mirror.)An astounding announcement, but an incontrovertible fact, as shown by the following festive arrangements, made wholly from names of members returned forming the new legislature.

At the head of the table will be found, in A' Court Style, a Blunt, Harty, King, dressed in Green and Scarlett, seated on a Lion—supported on the right by three Thynne Fellows and two Bastard Knights, Baring a Shiel; and on the left by a Sadler, seven Smiths, and the Taylor "wot" Mangles with his Bodkin. The bottom, it is understood, will be graced by a Mandeville on a Ramsbottom, with a White Rose at each elbow, and a Forrester and Carter on one side, and a Constable and Clerk on the other. The sides will contain a Host of unknown Folks.

Lamb, dressed by an English Cooke, will be one of the principal joints; and birds being scarce this season, there will only be a Heron, two Martins, a couple of Young Drakes, and a Wild Croaker. There will, however, be an immense Lott of French Currie, and the Best Boyle Rice. Fruit being yet unripe, there will consequently only be some Peach and Lemon Peel.

The whole will be got up at a great Price; but in order to go a Pennefather, the amusements of the evening are to be further promoted by the performance of Dick Strutt, the celebrated Millbank Ryder, who will Mount a Hill, and afterwards, while swallowing a Long Pole, blow a Horn fantasie through his nose without Pain, and then Skipwith a live Buck and two Foxes—concluding with a description of his late two Miles Hunt in three Woods.

Among the splendid pictures decorating the walls, are some views along the Surry Banks and of the Bridges.

On the whole, some warm work is anticipated, from there being a supply of both Coke and Cole; but as to who will Wynne, remains to be seen.

WalworthG.WEPITAPHS

On Ann Jennings, at Wolstanton.

Some have children, some have none;Here lies the mother of twenty-one.On Du Bois, born in a baggage-wagon, and killed in a duel.

Begot in a cart, in a cart first drew breath,Carte and tierce was his life, and a carte was his death.On a Publican.

A jolly landlord once was I,And kept the Old King's Head hard by,Sold mead and gin, cider and beer,And eke all other kinds of cheer,Till Death my license took away,And put me in this house of clay:A house at which you all must call,Sooner or later, great and small.On John Underwood.

Oh cruel Death, that dost no good,With thy destructive maggots;Now thou hast cropt our Underwood,What shall we do for fagots?In Dorchester Churchyard.

Frank from his Betty snatch'd by Fate,Shows how uncertain is our state;He smiled at morn, at noon lay dead—Flung from a horse that kick'd his head.But tho' he's gone, from tears refrain,At judgment he'll get up again.EPITAPHS IN BROMSGROVE CHURCHYARD

In memory of Thomas Maningly, who died 3rd of May, 1819, aged 28 years.

Beneath this stone lies the remains,Who in Bromsgrove-street was slain;A currier with his knife did the deed,And left me in the street to bleed;But when archangel's trump shall sound,And souls to bodies join, that murdererI hope will see my soul in heaven shine.Edward Hill, died 1st of January, 1800, aged 70.

He now in silence here remains,(Who fought with Wolf on Abraham's plains);E'en so will Mary Hill, his wife,When God shall please to take her life.'Twas Edward Hill, their only son,Who caused the writing on this stone.We perceive that Mr. Murray has advertised the second edition of Sir Humphry Davy's Salmonia, with the following opinion quoted from the Gentleman's Magazine: "One of the most delightful labours of leisure ever seen—not a few of the most beautiful phenomena of nature are here lucidly explained." Now, these identical words occur in our Memoir of Sir H. Davy prefixed to vol. xiii. of The Mirror, and published in July, 1829. A Memoir of Sir Humphry Davy appeared subsequently in the Gentleman's Magazine of the same year, in which the editor has most unceremoniously borrowed the original portion of our Memoir (among which is that quoted above), without a single line of acknowledgment. He has, too, printed this matter in his largest type, while we were content to write and sell the whole Memoir and Portrait at our usual cheap rate.

1

We quote these passages from an excellent description of Virginia Water, in the Third Series of the London Magazine, and, for the most part quoted in vol. xii. of The Mirror. The reader should turn to these pages.

2

The epithet bald, applied to this species, whose head is thickly covered with feathers, is equally improper and absurd with the titles goatsucker, kingsfisher, &c. bestowed on others, and seems to have been occasioned by the white appearance of the head, when contrasted with, the dark colour of the rest of the plumage. The appellation, however, being now almost universal, is retained in the following pages.

3

With such a poem as this, even occasionally, the Metropolitan must take high ground.