полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 493, June 11, 1831

FRUITS OF INDUSTRY

Last week the friends and supporters of the Metropolitan Charity Schools dined together at a tavern in the city. Among the toasts were "the Sheriffs of London and Middlesex," upon which (one of them,) Sir Chapman Marshall, returned thanks in the following plain, sensible words:

"My Lord Mayor and gentlemen, I want words to express the emotions of my heart. You now see before you an humble individual who has been educated in a parochial school. (Loud cheers.) I came to London in 1803, without a shilling—without a friend. I have not had the advantage of a classical education, therefore you will excuse my defects of language. (Cheers.) But this I will say, my Lord Mayor and gentlemen, that you witness in me what may be done by the earnest application of honest industry; and I trust that my example may induce others to aspire, by the same means, to the distinguished situation which I have now the honour to fill. (Repeated plaudits.)"

In its way, this brief address is as valuable as Hogarth's print of the Apprentices.

FRENCH POETRY FOR CHILDREN

M. Ventouillac, editor of a popular Selection from the French Classics, has professionally experienced the want of a book of French Poetry for Children, and to supply this desideratum, has produced a little volume with the above title. It consists of brief extracts, in two parts—1. From Morel's Moral de l'enfance; 2. Miscellaneous Poems, Fables, &c., by approved writers; and is in French just what Miss Aikin's pretty poetical selection is in English. We hope it may become as popular in schools and private tuition; and we feel confident that M. Ventouillac's good taste as an editor will do much by way of recommending his work to the notice of all engaged in the instruction of youth.

BLUE BEARD

The original Blue Beard who has, during our childhood, so often served to interest and alarm our imaginations, though for better dramatic effect, perhaps, Mr. Colman has turned into a Turk—for surely the murderer of seven wives could be little else—was no other than Gilles, Marquess de Laval, a marshal of France, a general of great intrepidity, who distinguished himself, in the reigns of Charles the Sixth and Seventh, by his courage, especially against the English, when they invaded France. The services that he rendered his country might have immortalized his name, had he not for ever blotted his glory by the most terrible murders, impieties, and debaucheries. His revenues were princely; but his prodigalities might have made an emperor a bankrupt. Wherever he went, he had in his suite a seraglio, a company of actors, a band of musicians, a society of sorcerers, a great number of cooks, packs of dogs of various kinds, and above 200 led horses. Mezeray says that he encouraged and maintained sorcerers to discover hidden treasures, and corrupted young persons of both sexes, that he might attach them to him; and afterwards killed them for the sake of their blood, which was necessary to form his charms and incantations. Such horrid excesses are credible when we recollect the age of ignorance and barbarity in which they were practised. He was at length (for some state crime against the Duke of Brittany) sentenced to be burnt alive in a field at Nantes, in 1440; but the Duke, who witnessed the execution, so far mitigated the sentence, that he was first strangled, then burnt, and his ashes interred. He confessed, before his death, "that all his excesses were derived from his wretched education," though descended from one of the most illustrious families in the kingdom.

EFFECT OF STEAM-COACHES

In a recent No. of the Voice of Humanity, (already noticed in the Mirror,) occurs the following:

We doubt whether our labours to accomplish either of the objects of this publication, if ever so successful, could produce such complete mitigation (rather abolition) of animal suffering as the substitution of locomotive machinery for the inhuman, merciless treatment of horses in our stage-coaches. The man who started the first steam-carriage was the greatest benefactor to the cause of humanity the world ever had. But in a political view the subject is very important. We have a superabundant population with a very limited territory, while each horse requires a greater quantity of land than would be sufficient to support a man. How extensive then would be the beneficial effect of withdrawing two-thirds of the horses and appropriating the land required for them to the rearing of cattle and to agricultural produce? The Liverpool and Manchester steam-coaches have driven fourteen horse-coaches off the road. Each of the horse-coaches employed twelve horses—there being three stages, and a change of four horses each stage. The total horses employed by these coaches was therefore 168. Now each horse consumes, on an average, in pasture, hay, and corn, annually, the produce of one and a half acre. The whole would thus consume the produce of 252 acres. Suppose, therefore, "every man had his acre" upon which to rear his family, which some politicians have deemed sufficient, the maintenance of 252 families is gained to the country by these steam-coaches. The average number in families is six, that is, four children, besides the father and mother.—The subsistence of 1,512 individuals is thus attained.

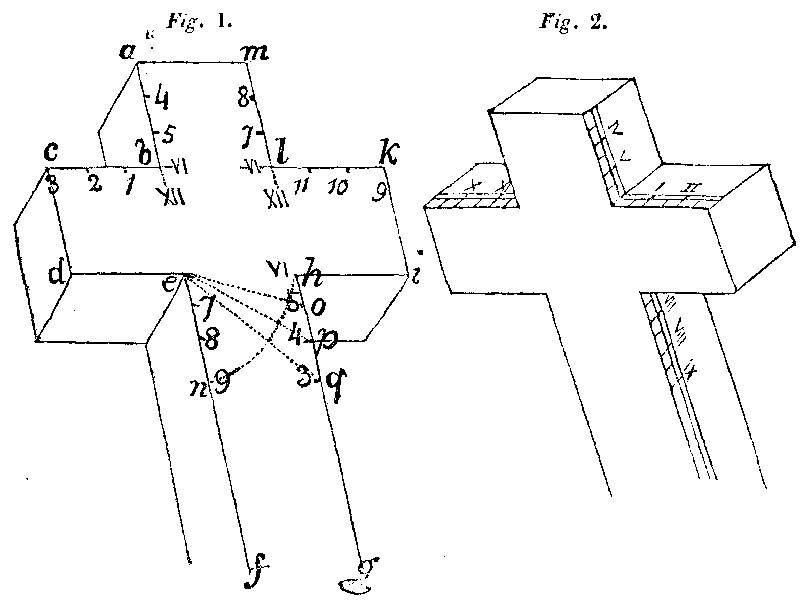

DIALLING

(For the Mirror.)The following method of constructing a dial, may be novel and interesting to many of those readers of the Mirror who are fond of that ancient art; whilst its simplicity and the great ease with which it may be constructed, will render it acceptable to all.

To make a Cross Dial.—A cross dial is one which shows the time of the day without a gnomon, by a shadow of one part of the dial itself, appearing upon another part thereof. Observe.—In making this dial you need have no regard to the latitude of the situation, for that is to be considered in the placing, and not in the making of it. 1st. Prepare a piece of wood or stone of what size you please, and fashion it in the form of a cross (see fig. 1) so that ab, bc, cd, de, eh, hi, ik, kl, lm, and ma, may be all equal: the length of ef is immaterial, it may be more than double to a e. 2ndly. Set one foot of your compasses in e and describe the arc h n, which divide into six equal parts for six hours, because it is a quarter of a circle; lay a ruler from e to the three first divisions, and draw the lines e o, e p, e q. 3rdly. Now the position of this dial being such that its end a m must face the south, and the upper part of it or the line a f lying parallel to the equinoctial, it is evident that the sun at noon will shine just along the line a b, and m l; therefore you must place 12 at b and l, then from 12 to 3 P.M. the shadow of the corner a will pass along the line b c, therefore take from the quadrant h n, the distance h o, and set it from 12 to 1. Take also h p and set it from 12 to 2, h q being equal to b c; at c you may place 3 where the shadow of the corner a goes quite off the dial at c, or 3 o'clock in the afternoon; at this time the shadow of the corner i will appear on the side h g at q or 3 o'clock, where place the figure 3; the shadow will then ascend to p at 4, to o at 5; at 6 there will be no shadow, the sun shining right along the line i h; place a VI also at the corner l, because it also shines along the line l k, and from 6 till 9, (if it be in a latitude where the sun continues up so late) the shadow of the corner at k is passing along the line l m: therefore take the distances h o, &c., and set off from 6 to 7 and from 6 to 8, as before at 12, 1, and 2. Then for the morning hours, the shadow of the corner c will enter upon the line a b at the point a, just at 3 o'clock in the morning, and if you draw lines from 7 and 8 parallel to a m, their terminations will point out 4 and 5. Six o'clock is in the very corner opposite to 6 in the evening. Parallel lines below the transverse piece drawn from 5, 4, 3, will indicate the proper places for 7, 8, 9. It then remains to set off the same distances as before on line l k on which the shadow of m will point out 11, 10, and 9 o'clock; the dial will then be finished.

Observe. These dials require considerable thickness (let it be equal to a m,) because being placed parallel to the equator, the sun shines upon the upper face till the summer, and on the longest day is elevated 23° 29' above the plane of the dial, and consequently the shadow of a will fall at noon in the line a b, not in the point b, but at an angle of 23° 29' therewith, and on the shortest day the like angle will be formed, but in an opposite direction. It must further be observed that after the proper points are determined on the plane, they had better be transferred to the sides of the cross, as is shown in fig. 2, for there it is the shadow will be seen to pass. A dial thus formed is universal; when made according to the foregoing directions there is nothing more to do but to fix it by the help of your quadrant to the elevation of the equinoctial or complement of the latitude of your habitation, and so that the side a m may exactly face the south. A dial of this sort has been standing in my garden, more than 12 months, and is found to answer the purpose well, being both useful and ornamental.

When the figures are painted on the thickness as in fig. 2, the upper surface being unoccupied, an equinoctial dial may be described thereon, which will be useful the summer half year, while on the lower surface a similar one may be placed for the winter half; or it may be made the bearer of some useful lesson, in the form of a motto, e.g. "Disce dies numerare tuos." But this is only a hint to the curious.

COLBOURNESturminster Newton, DorsetThe Selector

AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS. ATHERTON,

By the author of Rank and TalentThis tale bids fair to enjoy more lasting popularity than either of the author's previous works. It has more story and incident, though not enough for the novel. The characters, if not new, are more strongly drawn—their colouring is finer—their humour is richer and broader, and as they are from the last century, so their drawing reminds us forcibly of the writers of the same period. There is none of the mawkish affectation of the writing of the present day, as coinage of words and fantasies of phrases which will scarcely be understood, much less relished, twenty years hence. But the style throughout is plain, sensible, and natural, free from caricature, and more that of the world than of the book.

The plot is of the tale or adventure description; certainly not new, but its interest turns upon points which will never cease to attract a reader. We do not enter into it, but prefer taking a few of the characters to show the rank of life as well as the style of the materials. The first is a portrait of a London citizen sixty years since:—

At the Pewter Platter there were two arm chairs, one near the door and the other near the window, and both close by the fire, which were invariably occupied by the same gentlemen. One of these was Mr. Bryant, citizen and stationer, but not bookseller, save that he sold bibles, prayer-books and almanacks; for he seriously considered that the armorial bearings of the Stationers' Company displaying three books between a chevron, or something of that kind, for he was not a dab at heraldry, mystically and gravely set forth that no good citizen had occasion for more than three books, viz. bible, prayer-book and almanack. Mr. Bryant was a bachelor of some sixty years old or thereabouts. He had a snug little business though but a small establishment; for it was his maxim not to keep more cats than would catch mice. His establishment consisted of only two individuals; a housekeeper and an apprentice. His housekeeper was one Mrs. Dickinson, a staid, sober, matronly looking personage, who tried very hard, but not very successfully, to pass for about forty years of age; the good woman, though called Mrs. Dickinson, was a spinster, and according to her own account was of a good family, for her great uncle was a clergyman. She was remarkable for the neatness of her dress, for the fineness of her muslin aprons, and the accurate arrangement of her plaited caps. In one respect Mr. Bryant thought that she carried her love of dress too far, for she would always wear a hoop when her day's work was done. Mr. Bryant's apprentice, who was at the period of which we are writing, nearly out of his time, was a high spirited young man, whom neither Mr. Bryant nor Mrs. Dickinson could keep in any tolerable order. So far from confining his reading to bibles, prayer-books, and almanacks, he would devour with the utmost eagerness, whenever he could lay his hands upon them, novels, plays, poems, romances, and political pamphlets; he was a constant frequenter of the theatres, sometimes with leave and sometimes without, for Mr. Bryant was almost afraid of him; and to crown the matter he was a most outrageous Wilkite.

Mr. Bryant himself was a neat, quiet, orderly sort of a man, regular as clockwork, and steady as time, the very pink of punctuality and the essence of exactness. He had been in business nearly forty years, in the same shop, conducted precisely in the same style as in the days of his predecessors; he lacked not store of clothes or change of wigs, but his clothes and wigs and three cornered hats were so like each other, that they seemed, as it were, part of himself. His wig was brown, so were his coat and waistcoat, which were nearly of equal length. He wore short black breeches with paste buckles, speckled worsted hose and very large shoes with very large silver buckles. He was most intensely and entirely a citizen. He loved the city with an undivided attachment. He loved the sound of its bells, and the noise of its carts and coaches; he loved the colour of its mud and the canopy of its smoke; he loved its November fogs, and enjoyed the music of its street musicians and its itinerant merchants; he loved all its institutions civil and religious; he thought there was wisdom in them if there was wisdom in nothing else; he loved the church and he loved the steeple, and the parson who did the duty and the parson who did not do the duty; and he loved the clerk and the sexton and the parish beadle with his broad gold-laced hat, and cane of striking authority; and he loved the watchmen and their drowsy drawl of "past umph a' clock;" he loved the charity schools and admired beyond all the sculpture of Phidias, or the marble miracles of the Parthenon, the two full-length statues about three feet each in length and two feet six inches each in breadth, representing a charity boy and a charity girl, standing over the door of the parish school; he loved the city companies, their halls, their balls, though he never danced at them, their dinners, for he never missed them; and above all other companies he loved the stationers', and its handsome barge, and its glorious monopoly of almanacks; he loved the Lord Mayor and the Mansion-house,—it was not quite so black then, as it is now,—and he loved the great lumbering state coach and the little gingerbread sheriffs' coaches, and loved the aldermen, and deputies and common-councilmen and liverymen. Out of London he knew nothing;—he believed that the Thames ran into the sea, because he had read at school, that all rivers run into the sea, but what the sea was he did not know and did not care; he believed that there were regions beyond Highgate, and that the earth was habitable farther westward than Hyde Park corner; but he had never explored those remote districts. What was Hammersmith to him or he to Hammersmith? He knew of nothing, thought of nothing, and could conceive of nothing more honourable, more dignified, or more desirable than a good business properly attended to. He was proud of the close and personal attention that he paid to his shop,—somewhat censoriously proud; he might be called a mercantile prude; or shopkeeping pedant; and when a near neighbour who had a country house at Kentish-town, to which he went down every Saturday, and from which he returned every Monday or Tuesday, came by a variety of unavoidable, or unavoided misfortunes to make his appearance in the Gazette, with a "Whereas" prefixed to his name, Mr. Bryant rather uncandidly chuckled and said, "I don't wonder at it. I thought it would end in that. That comes from leaving things to boys."

Much as Mr. Bryant venerated the city, and all the city institutions, yet he was by no means ambitious of its honours. His motives of abstinence were of a mixed nature. He had fears that the dignity of common-councilman, which he had occasionally been invited to aspire to, might interfere with his domestic comforts and put Mrs. Dickinson out of her way; and he had some slight apprehensions that he might not be successful if he should make the attempt; and then as in the course of his life he had seen many promoted to that honour, whom he had once known as children and apprentices, and whom he still regarded as boys, though some of them were upwards of thirty years old, he affected to make light of a dignity that had become so cheap.

Mr. Bryant was considered by the frequenters of the Pewter Platter as a man of substance, and being some years older than most of the visitors at that house, and having been accustomed to the house for more years than any other of the party, the arm-chair, at what was called the upper side of the fire-place, was invariably reserved for him, and the other arm chair was most frequently occupied by the Rev. Simon Plush. This reverend gentleman was a specimen of a class of clergy now happily extinct, and never it is to be hoped for the honour of the church, likely to be revived. He was a tall, muscular, awkward man, about fifty years of age; habited in a rusty grey coat, with waistcoat and breeches of greasy black, wearing a grizzled wig that had shrunk from his forehead, which in its broad expanse of shining whiteness, formed a contrast with a fiery hooked nose with aldermanic decorations. His gait was shuffling and awkward, and all his carriage was that of a man who was a sloven in everything; he was slovenly in his dress, slovenly in his behaviour, slovenly in mind. He had been a servitor at Oxford, where it can hardly be said that he had received his education, for though an education had been offered to him both at school and at Oxford, he had, in both instances, declined the offer, guessing, perhaps, that with such a mind as his, the acquisition of mental furniture would be but labour lost. By the tender mercy however, or by the culpable negligence of college dignitaries and examining chaplains, he had found his way into the clerical profession, and had undergone the imposition of episcopal hands, which was rather an imposition on the public than on him. Yet he lacked not talent of some kind; he was a good hand at whist, excellent at cudgel playing, dexterous on the bowling-green, capital at quoits, unparalleled at rowing a skiff, could play well at nine-pins, could run, hop, skip, jump or whistle with any man of his years, not ignorant of the science of self-defence, and when rudely or ruffianly insulted, could repay the indignity, with interest, at a moment's notice; his lungs were vigorous, he could blow the French horn with most poetic and potential blast, and with no mean degree of skill, and as for preaching he made nothing of it; it used to be said that, with the assistance of a dexterous parish clerk, he could get through the whole morning service, sermon and all, in five and thirty minutes; he was no spoil-pudding except where he dined. With all these talents, however, he had no preferment in the church, nor even a curacy; but he had plenty of duty to do of one kind or another, and as all his work was piece-work, he got through it with as much rapidity as possible. He was in almost constant requisition, and could be found any morning at the Chapter Coffee House, or any evening at the Pewter Platter, except Sunday, and he usually spent his Sunday evenings at Mr. Bryant's. Mr. Plush was one who prudently avoided meddling with politics, "For who knows," said he, "but that it may some day or other cost me a dinner?" He was for the most part tolerably loyal, but democratic beef would not choke him. To crown the whole, he was imperturbably good-natured.

Early in the first volume we are introduced to Wilkes and Doctor Johnson: this is rather a hazardous experiment of the author, but is executed with success. Atherton, the hero, is then a city apprentice. These were the days of Wilkes and Liberty, and Atherton, through his protracted attachment to the cause, is locked out by his master, John Bryant.

As Atherton stood absorbed in thought at the eastern side of Temple Bar, he was wakened from his reverie by two gentlemen coming through the gate and talking somewhat loudly. One of them was a ponderous, burly figure of rolling and shuffling gait puffing like a grampus, and at his side staggered or skipped along a younger, slenderer person, who hung swingingly and uncertainly on the arm of his elderly companion. The older of the two was growling out something of a reproof to his unsteady companion, who flourished his arm as with the action of an orator and hiccupped according to the best of his then ability something like apology or vindication. The effect of this action was to throw him off his balance, to unlock his arm from his more steady supporter and to send himself with a hopping reel off the pavement. To a dead certainty he would have deposited his unsober self in the kennel had he not been kindly and vigorously intercepted in his fall by the ready assistance of Frank Atherton. At the ludicrous figure which his staggering friend now made the older gentleman burst into a roar of laughter which might have been heard from Charing Cross to St. Paul's; but suddenly checking himself he mournfully shook his head saying, "Oh Bozzy, Bozzy, this is too bad."

Frank, having no other occupation, was ready enough to offer his assistance towards guiding and propping the intoxicated gentleman; for it seemed to be a task rather too hard for the sober one to manage by himself.

"I am sorry to take you out of your way;" said the old gentleman to Atherton.

"You cannot easily do that," replied Frank, "I have no particular destination at present. My way lies in one direction as well as in another."

"Do I understand you rightly?" asked the stranger, "Are you indeed a houseless, homeless wanderer."

"I cannot justly call myself a homeless wanderer," said Frank, "but my master has just now closed his doors on me and I have no other home at present than the streets."

"'Tis bad, 'tis bad," said the gentleman, "you or your master has much to answer for. But I'll take care you shall not want a shelter for the present. I will not have upon my conscience the guilt of suffering you to roam about the streets all night, if I can prevent it."

Frank was of a grateful disposition, and was so much struck with the considerate kindness of the old gentleman that he ardently exclaimed, "Sir, I shall be infinitely obliged to you."

"Nay, nay," replied the stranger, "you speak profanely. You cannot be infinitely obliged to any man."

The party then entered a house in one of the courts of Fleet street and Frank felt happy in having met with one likely to befriend him. For though the gentleman was rather pompous in his manners and somewhat awful in his aspect, yet there was a look of kindness about him and an expression of humanity and consideration in his countenance. When the intoxicated gentleman had been seated for a few minutes, his faculties partially returned and looking, or rather endeavouring to look upon Atherton, for his eye was not steady enough to take a good aim, he said: "Young gentleman, I am very highly obli—obli—obligat—"

"Obligated," roared the old gentleman, "you would say. But you had better hold your tongue. That is the best use you can make of it."